Vik Muniz

My mind is bent to tell of bodies changed into new forms. Ovid

Miracles happen, not in opposition to nature but in opposition to what we know about nature. St. Augustine

Things look like things, they are embedded in the transience of each other’s meaning; a thing looks like a thing, which looks like another thing, or another. This eternal ricocheting of meaning throughout the elemental proves representation to be natural and nature to be representational. Vik Muniz

I pondered deeply, then, over the adventures of the jungle. And after some work with a colored pencil I succeeded in making my first drawing. My Drawing Number One. … I showed my masterpiece to the grown-ups, and asked them whether the drawing frightened them. But they answered: “Frighten? Why should any one be frightened by a hat?” My picture was not a picture of a hat. It was a picture of a boa constrictor digesting an elephant. But since grown-ups were not able to understand it, 1 made another drawing: I drew the inside of the boa constrictor, so that the grown-ups could see it clearly. They always need to have things explained. Saint-Exupery, The Little Prince

(A) Resembling Childhood

Mists gathered outside the house each evening, ephemeral tentacles slipped along roof gutters snaking their way into darkened rooms. In this part of the world the air is heavy during the day at night it is chunky, humidity as palpable as cotton balls. A boy lies in bed staring at the ever-shifting moisture stain in the plaster ceiling directly above head upon pillow. Over the course of several weeks of these nightly morphing sessions, images grow in the clarity of their representation. As in time-lapse photography, an image reaches a fullness of recognition and then fades like a shriveling blossom. An ambiguous, scruffy outline begins to resemble the face of a clown, gradually the perimeter of the globular nose on the clown’s face grows and reaches the arches of the painted eyebrows, the nose becomes a cratered planet. Several nights later a system of tiny capillaries appears, transforming the former nose into a spider’s web. A week passes and the web has sagged beyond recognition but has settled comfortably into an image of soccer net, complete with a miniature Pele, arms raised in the ecstasy of victory. The boy’s night lessons are full these transformations, a conjugation of forms; he internalizes and projects a pictographic language that is both ancient and modern, idiosyncratic and cultural. He even keeps a kind of visual diary that cumulatively chronicles the vast bestiary of his nocturnal observations.

The child owns nothing of the world, and as if to make up for this material poverty the universe bestows all of its wonder. Under every rock, in each nervous shadow, and in the shape of every cumulus cloud there lays the dialectic of mystery and recognition. A child’s relationship to the world is porous; the outside is animated by the child’s imagination, and the child, in turn, is animated by the multitude of wonders that surrounds him. The difference between itself and things, both animate and inanimate, is less fixed than it is in the petrified certitude of adults. Occupying the space beneath the kitchen table while mom and dad, aunts and uncles and assorted grown-ups argue and laugh loudly, the child envisions the spindly disembodied legs as the multiple serpentine snouts of the beast that provides the heat for the child’s underground hideaway. Who among us does not remember how something as fundamentally mute as a mud puddle could come alive as the primeval ooze? We filled our world with creatures and stories, and in turn these creations kept us company, helping us negotiate the foreign cultures of the tall people who owned everything.

Childhood is a blessing of un-self-consciousness. For a preciously short time in childhood we are unaware of ourselves as an image, we have not internalized the external gaze of authority. We own nothing; have no power, yet we are free. The foundational narrative of the West is found in the Book of Genesis; it is a story all about naming, authority, forbidden knowledge, and self-consciousness. In Eden, beyond being fruitful and multiplying, Adam and Eve had little to do after the naming of all things. They were, briefly, without shame; unaware of themselves as seen from the outside, they lived in harmony with all creatures great and small.

I believe the metaphor of the Peaceable Kingdom has everything to do with our lost childhood power of imaginative naming and our blissful ignorance of ourselves as an image. To add insult to injury, the unceremonious eviction from Eden came with the curse of self-consciousness; our beloved ancestors covered themselves with hastily tailored bits of clothing. This curse has resulted in a cultural lifetime of self-control, self-censorship, and estrangement from unadulterated wonder. We seldom, if ever, contentedly sit under the kitchen table as grown-ups.

There are other formative uncertainties that shade this specific boy’s life, growing up in Sao Paulo, Brazil during the 1960s and ’70s as the military holds the country hostage in a seemingly constant state of emergency. For the citizens of this blessed and cursed Amazonian kingdom, fIxed positions vis-à-vis politics, culture, history, class, memory, and even the meaning of words are to be avoided. Sons and daughters, teachers and peasants, artists and union organizers, social workers and politicians often disappear without a trace. Between work and home, the dentist’s office and a dinner date, or ripped from forgetful sleep, lives are interrupted without mercy. Explanations from the authorities are, of course, not forthcoming; one wonders whether a slip or the tongue or an unsuspecting friendship with an enemy of the state will transform one into a non-person. Citizens taken into custody with books are doubly suspect: there are special interrogators reserved for those caught with the fruit of the tree of knowledge. As Edmund Burke wrote in 1757, “To make any thing terrible, obscurity seems in general to be necessary.'” What can anything possibly mean when all meaning potentially threatens? A terror of absence settles on those that remain; the disappeared ones are, paradoxically, signifiers of the ultimate power of the state. Unavoidably, explicitly and through osmosis, these conditions encode themselves upon the boy’s imagination, coloring his overpopulated internal landscape with an atmosphere of ambiguity.

The boy’s parents are working class, his mother a switchboard operator, his father a bartender. One evening the father comes home, standing on the street calling his son to come out of the house. In the grainy light of the street lamp, his father stands holding the handles of a wheelbarrow in which rests a complete set of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, won in a game of billiards. Growing up in a house without books, this treasure trove of information will act as the mortar with which to build a bridge to the outside world. Starter encyclopedias usually go by the name of “Little Book of Wonders” or some such fancy. If we are lucky and/or predisposed to subtleties, at some point in childhood we realize that there are at least two types of “wonder” involved in such presentations. There is the thing itself presented in “words and images, whether it be pictures of grazing giraffes or illustrations of water molecules. The second level of wonderment is generated by the realization that representations themselves are strange, quirky, difficult to identity, and that sometimes they reveal more about the processes of perception and the limits of communication than what is conveyed about the subject itself. This boy in particular is fascinated by the transformation of photographic and graphic illustrations into a semiotic gray area as a result of the cheap reproductions found on the impossibly thin pages of the Britannica. The tiny halftone photographs look like bad drawings and the murky graphics look like poor photographs. If the purpose of these images is to demystify the wonders of the world in direct, compact, and digestible fragments, they have the opposite effect for this artist-in-the-making, who finds ambiguity, mystery, and wonder in the muddy-gray tonalities of encyclopedic marginalia.

(B) Pictures in Stone

Vik Muniz is an artist who remains motivated by wonder and inexorably drawn toward ambiguity, who finds delight in the indeterminacy of images. He fancies himself a “low-tech illusionist” in search of perceptual sleight-of-hand that revels in its trickery but still retains the transformative power of magic. A quick review of a few items from his bag of tricks suggests the subversive play of the Muniz cabinet of wonders. Tufts of cotton are shaped like miraculous free-floating topiary, we know it is cotton, yet we see them as clouds, we know they are clouds but recognize them as praying hands. Another example is the image of thin graphite-like lines describing the outlines of a dripping faucet, but upon closer inspection we realize it is not a drawing but a photograph, and the photograph shows a length of twisted wire tacked to a white wall, a simple sculpture masquerading as a drawing. Thirdly, we think we recognize a well-known image from the collective memory archives, we silently mutter the name “Vietnam” under our breath, but we discover that the composition or the perspective seems to have soured; it is not exactly how we remember it. Again we are fooled, the image that plugged so readily into our repository is really a forgery, a handmade counterfeit, a drawing of a photograph that has been photographed. The Muniz archive is a collection of pictures imitating other pictures, an eccentric celebration of what he calls “the unbearable likeness of being,” and the cumulative effect of his work maps out a rudimentary language of resemblances, an alphabet of likeness.

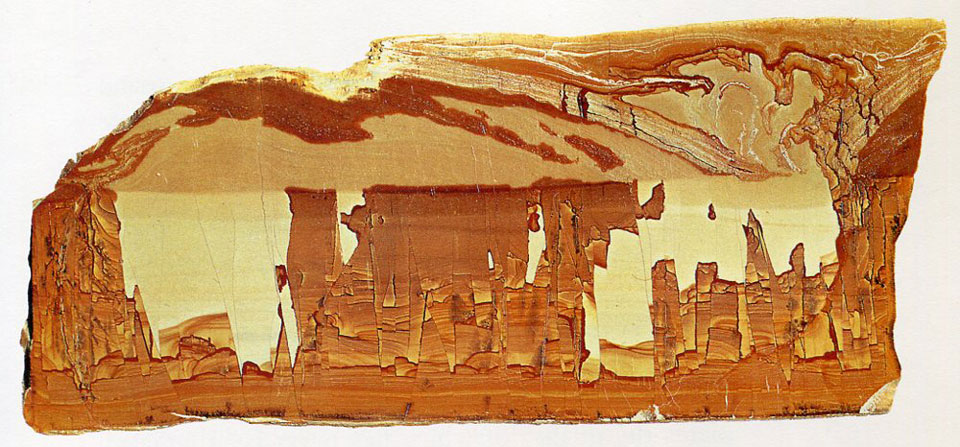

“There are impossible scribblings in nature, written by neither men nor devils.” So states Roger Caillois in his fanciful yet compelling meditation on the origin of human aesthetics, The Writing of Stones. Caillois explores visual language in natural forms and in particular images as found in split and polished pieces of silica, agate, marble, or “picture stones” as they are known, which bear uncanny resemblances to every conceivable natural phenomenon and human invention. As Marguerite Yourcenar observed in her introduction, contrary to accusations of anthropomorphism, Caillois proposed that human aesthetics were but part of a larger universal order of beauty. Found in polished “picture stones” are representations of both organic and inorganic structures, landscapes and castles, portraits and holy apparitions. Caillois suggests that humans learned about representation through images that already existed in nature.

These [models of nature] consist of subtle and ambiguous signals reminding us, through all sorts of filters and obstacles, that there must be a pre-existing general beauty vaster than that perceived by human intuition – a beauty in which man delights and which in his time he is proud to create. “Stones – and not only they, but roots, shells, wings and every other cipher and construction in nature – help to give us an idea of the proportions and laws of that general beauty about which human beauty must be mere one recipe among others…”

Simply put, the visual workings of nature were our first art teacher; lesson one involved discovering images in natural forms that resembled our experience of the world. Before a Neanderthal proto-Rembrandt etched an antelope on the cave wall, perhaps he noticed a water stain that reminded him of his favorite meal. This recognition gave him pleasure for it stirred feelings of desire, violence, and satiation, and then he noticed-quite dimly, for he was a Neanderthal after all- that the water stain/antelope image would look better if he scratched a circle where the eye would be and maybe if he extended the antlers just so, the overall impression would be more lifelike, which to his mind was good. This is an apocryphal tale of the first artistic collaboration in which our low-browed ancestor began the long road of aesthetic evolution by attempting to imitate and improve upon a preexisting iconography created by natural forces. In this way, Caillois believes that representation itself is first and foremost “natural,” and human culture’s obsession to identify and re-create images is a primordial impulse.

(C) It Looks a Lot Like Life

To see life; to see the world; to eyewitness great events; to watch the faces of the poor and the gestures of the proud; to see strange things-machines, armies, multitudes, shadows in the jungle and on the moon; to see man’s work-his paintings, towers, discoveries; to see things thousands of miles away, things hidden behind walls and within rooms, things dangerous to come to; the women that men love and many children; to see and to take pleasure in seeing; to see and be amazed; to see and instructed.

So proposed Henry R. Luce in 1936 to establish a pictorial magazine named Life for the American masses. Human beings have had many art teachers throughout the millennia. In the modern world, photography has been an instructor like no other; and Life magazine has been the syllabus. After coming to the United States in 1983, Vik Muniz found a copy of The Best of Life at a garage sale outside of Chicago. Still negotiating the rudiments of English, photographic images were the primary language for his introduction to American Culture. Luce’s adviso “to see and take pleasure in seeing; to see and be amazed; to see and be instructed” found an eager student in Muniz. As represented in Life magazine, American culture seems oddly choreographed and melodramatic, a place seemingly without hierarchies of historical importance: a hula-hoop gyrates adjacent to a mushroom cloud and an assassination on the streets of Saigon segues into hippies on Haight Street.

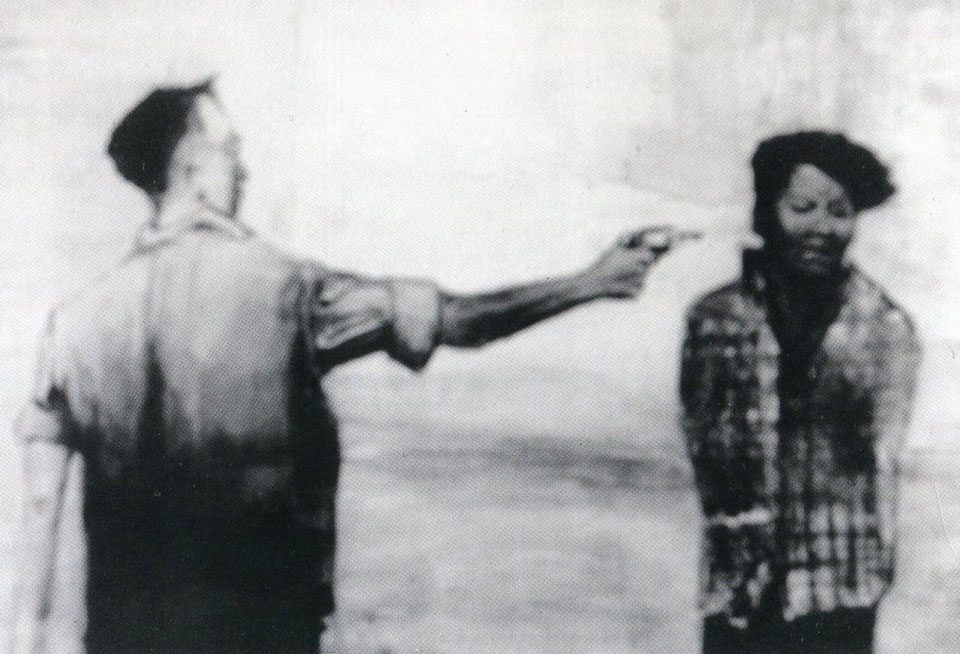

Some years later in 1989, Muniz attempts to recall from memory these iconographic moments from American history in his own Best of Life series. What is revealed, among other things, is how insidiously Henry Luce’s family album has seeped into our nation’s collective consciousness. Life’s images have become the anchors to our memory. Photographs are, paradoxically, both fragmentary and iconographic: they represent moments severed from the linearity of time, yet they promise an almost seamless access to the world. When we look at a photograph we generally say “This is my mother,” not “This is a picture of my mother.” This difference is crucial in understanding the seductive power of representation that photography holds. Photography is a magician who seldom slips up, whose illusions are always perfect, thereby never calling attention to the trick of turning an animated three-dimensional world into a two-dimensional static object. In his photographic transformations, Muniz aims to destabilize photography’s evidentiary power by deliberately undermining the truth of its communication.

The smudgy and awkward charcoal drawings Muniz dredged up from his memory banks cannot but remind us of the source: images such as theater audiences uniformly wearing 3-D glasses, a naked Vietnamese girl running down an incinerated road, or the summary execution of a suspected enemy on a Saigon street are all lodged deeply in our personal and collective memories. After photographing these memory renderings, Muniz printed them with a dot-screen pattern to mimic even more closely the original image. In The Best of Life series, he suggests that although these images may be seared in our consciousness, they exist solely in the rarefied realm of the symbolic, devoid of their original power. Perversely, his strategy seems to resuscitate these images, as if in their falseness they take on a new power to disturb. Like a renegade conjurer who reveals the machinations of illusion, or as when someone tries a magic trick that doesn’t work, something is revealed about the fundamentally hallucinatory quality of photographic representation.

I want to make the worst possible illusion that will still fool the eyes of the average person … Illusions as bad as mine make people aware of the fallacies of visual information and the pleasure to be derived from such Fallacies. These illusions are made to reveal the architecture of our concept of truth. They are meta-illusions. Vik Muniz

Upon moving to New York in 1984, Muniz began making sculptural objects, many of which toyed with perceptual differences between two- and three-dimensional representation. Three works from the late 1980s illustrate how he often combined photographs with objects that both contradicted and completed one another to create a conceptual whole. In Tug of War (1988) two photographs bracket and are connected by an actual piece of rope that hangs flaccidly between the two struggling adversaries. We get the joke without hesitation, yet there is something endearingly futile about the Herculean effort being made, not only to pull the line taut, but also to make the concept visually seamless. Cogito Ergo Sum (1989) presents a photographic image of tangled and knotted electrical wire within a frame. Actual wire carrying current is plugged into the socket in the wall below the frame, a light fixture rises above the frame, and in a gesture of delusional grandeur, the image illuminates itself. In Arrangements (1989), Muniz choreographed sixteen black-and-white photographs of the same Canadian goose in the pattern of a migrating flock. Again the illusion of visual logic is laid bare: We immediately comprehend the formula for meaning, recognizing the pattern from nature while simultaneously understanding its fabrication. This playful self-referentiality echoes the work of photographic conceptual artists such as Robert Cumming, Bruce Nauman, and John Baldessari.

As transitions between image and object, operating in the space between flatness and depth, Muniz found himself attracted to the photographic documents of his sculptural pieces more than the objects themselves. The photographs conveyed the conceptual rigor of the sculpture, yet added the hermetic lightness and the perceptual economy of photography. In 1991, with a fast-approaching exhibition deadline and little money to spend on materials, Muniz purchased a lump of plasticine and a few rolls of black-and-white 35mm film. Muniz shaped the plasticine into various fantastical figures, photographing each one before remolding the same material into another figure. This process resulted in approximately sixty photographed figures, or “individuals” as Muniz came to consider them; five dozen humble and quirky sculptures whose only proof of their short and charmed existence was the photographic document, which was also their portrait, their death mask, if you will. Muniz gave each one a human name – Veronica, Bob, Phil, Carrie, Amanda, etc. – and when time came for the exhibition, he exhibited the photographs along with empty pedestals which served as memorials for the lost presence of these poor departed souls. Symbolically, Muniz was also bidding farewell to sculpture and embracing photography as the sole vehicle for his ideas.

(D) I’ve Looked at Clouds From Both Sides Now

The cloud pictures (Equivalents) from 1993 are visually accessible yet resonate deeply with ideas from and referrals to art history and art theory. Looking at these pictures one might remember lying on one’s back, splayed in a meadow, thickly whipped white cumulus billowing overhead. One is hypnotically involved in the fauna of imagination, a process of perceptual transformation occurs as the eyes scan the heavens, coming to rest on a recognizable formation. As the bunny cloud becomes the Elmer Fudd apparition, we participate in an endless and seemingly random game of recognition and association. This memory/image of cloud gazing, whether it be actual or just a cultural trope, represents a kind of benevolent collaboration between the individual and the grand coincidences of nature. Is a recognizable apparition in the clouds any less miraculous than Jesus in a tortilla, a monumental face on Mars, or Etruscan ruins as they appear in a polished agate? What are these moments of reciprocity between natural phenomena and human perception? Again, to quote Caillois:

I see the origin of the irresistible attraction if metaphor and analogy, the explanation if our strange and permanent need to find similarities in things. I can scarcely refrain from suspecting some ancient, diffused magnetism; a call from the center if things; a dim, almost lost memory, or perhaps a presentiment, pointless in so puny a being, if a universal syntax.

The cloud pictures also recall Alfred Stieglitz’s images of atmospheric skies that he first exhibited in 1922. Initially titled Songs if the Sky and subsequently renamed Equivalents, Stieglitz pointed his camera skyward and later remarked, “My photographs are a picture of the chaos in the world, and of my relationship to that chaos. My prints show the world’s constant upsetting of man’s equilibrium, and his eternal battle to establish it.”

In terms of the history of the medium, much has been made of Stieglitz’s accomplishment with this body of work, in the sense that he utilized photography conceptually, establishing a method of working that was fundamentally different from slavishly mimicking the aesthetics of painting as was fashionable for the Pictorialist photographers of his day. Nor was he concerned with using photography to document social realities, as in the work of Lewis Hine, for example. For Stieglitz, his cloud pictures were like no others since photography’s inception, free of painterly and sociological constraints. He believed them to be powerful, transcendent, and liberating images for himself, the viewer, and finally for photography itself

While at the end of the twentieth century it is nearly impossible for an artist to make such metaphysical claims for his work without irony, Muniz is interested, in a more humble way, in the idea of negotiating meaning out of chaos. But meaning in a contemporary sense is not found in transcendent metaphors, and chaos is not to be located in the endlessly shifting shapes of nature but the ever-accumulating image archive of our personal and collective histories. For a modernist like Stieglitz, the heroic struggle for the artist was to find visual equivalents and natural analogues for internal states. Muniz is interested in something a bit less romantic: his images are experiments and hypotheses concerning the psychology of perception. He is not interested in the nature of the physical world but in our perceptual reaction to our image-saturated culture.

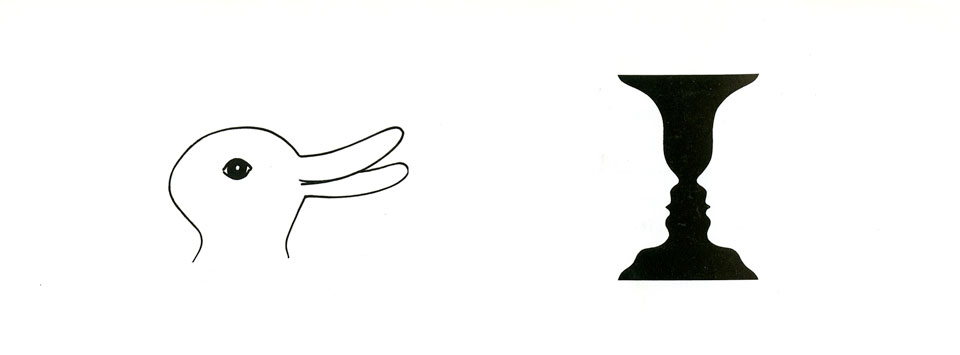

In Art and Illusion, E. H. Gombrich poses the fundamental question to representation: “Is it possible to see shape apart from its interpretation?” At the beginning of this hugely influential text, he presents a simple black-and-white illustration, an image that on one hand looks like a rabbit with swept-back ears and on the other a duck with beak slightly parted. We can fall back and forth between the two readings, yet it seems impossible to see both simultaneously.

True, we can switch from one reading to another with increasing rapidity; we will also “remember” the rabbit while we see the duck, but the more closely we watch ourselves, the more certainly we will discover that we cannot experience alternative readings at the same time. Illusion, we will find, is hard to describe or analyze, for though we may be intellectually aware of the fact that any given experience must be an illusion, we cannot, strictly speaking, watch ourselves having an illusion.

A tuft of cotton resembles a cloud that resembles a man in a gondola that reminds us of Stieglitz. In the process of switching our perceptual framework between the varying positions, we can almost feel the muscles of seeing and perceiving, we watch ourselves watching and are delighted in the magic of it. The psychology of perception is complex indeed and Gombrich proposes various theories, including a kind of perceptual trial and error in which everything we see either confirms or contradicts what we already know. Human consciousness, therefore, never ceases probing and testing its environment, moving from the general to the particular in the process of identification. This perceptual switchboard, it seems to me, is the structure for the subversive play of not only the cloud pictures but the entirety of the Muniz archive in which he exchanges the thing for an illusion of the thing, thereby forcing the viewer to experience the process of vision.

(E) An Icon Erased with the Slurp of a Tongue

Muniz is fond of telling a story about a Buddhist monk he met at the Asia Society in New York City who was publicly constructing an elaborate mandala out of sand. Day after day Muniz would visit the site, becoming hypnotically involved in watching the painstaking, methodical, and meditative ritual of pouring colored grains of sand in intricate patterns. The image of the mandala evolved from an accumulation of gestures as the monk’s hands gracefully hovered over the ground, wispy trickle gathering in a web of stunning simplicity. The mandala was finally complete after a week of intensive labor, and as the monk raised himself off the floor and gazed upon his creation, another monk arrived with a broom and dustpan. The creator of the mandala appeared unfazed by this almost Dada-like anti-art performance, and Muniz shuffled over to inquire how the monk could so peacefully accept the destruction of the beauty of his labor. As might be expected, initially the monk replied philosophically, claiming the process and labor were, in and of themselves, their own rewards. Prodded further, the monk continued to elaborate on the theme of letting go of materialism, that things of this world have no intrinsic value. Muniz the Mischievous questioned the monk more pointedly and finally, with a conspiratorial smile slowly gathering on his lips, the monk slyly pulled a camera from inside his robes saying, “At least I’ll have the photos.”

In the case of the photographs of Vik Muniz, one might be awed by the serenity or question the sanity of a man who would spend up to two weeks constructing an image out of sugar, dirt, or thread. Muniz moves every grain of soil and sugar crystal, he endlessly unwinds spools in intricate patterns only to photograph the resulting image once and then unceremoniously dump the product of his labor into the trash bin. The apparent simplicity of his images obscures the excruciating detail and laboriousness of the making. Muniz employs a tiny vacuum apparatus, cotton swabs with glue, tweezers, and brushes to rearrange and build density, highlight, and shadow out of bits of wood pulp and soil; granules of sugar are transported one by one as if by an oversized and single-minded ant in tent on making accurate the visage of a child. Imperceptible behind the whimsical accessibility of his work is a ravenous visual intelligence – he is forever shifting, sifting, making the strange recognizable and the familiar monstrous in a dialectic of connection and estrangement. In his world of materiaI, process, and illusion, Muniz – in the words of critic Andy Grundberg – “revels in the unstable territory between object and image, material and representation, fact and metaphor.” That unstable territory is like the suspended moment before a first kiss, full of mystery, and the giddy anticipation of revelation.

The Sugar Children series (1996) was inspired by a vacation-trip Muniz made to the Caribbean island of St. Kitts, where he met the children of workers in the sugar growing and processing industry, which along with tourism is the primary economic engine of the local economy Muniz spent much of his time hanging out with the kids of St. Kitts, getting to know them and making photographic portraits. The titles from this series indicate the personal rather than the sociological investment. Muniz had a relationship with these children: Big James Sweat Buckets, Valicia Bathes in Sunday Clothes, Jacynthe Loves Orange Juice are examples of intimacy between artist and subject. It is stating the obvious to observe that becoming cane-cutters in the sugar fields is the most likely fate for these children. The irony of utilizing the sweet substance of their servitude to portray them is not lost in these images. Yet there is something more than a glib political/conceptual equation at work here. The sugar pictures are heartbreakingly beautiful, simultaneously rough, and ephemeral, full of the light of childhood yet almost too delicate to last. Folds of granular whiteness gather on black paper, the grains of sugar mock the monetary and reproductive value of the silver grains of the photographic process. It is as if the production of sugar threatens to drain away the sweetness and presence of these children’s spirit, and that the “refined” product is somehow haunted by the ghost of their labor, past, present, and future.

There is a strong element of the performative in many of Muniz’s works, especially in the Chocolate and Thread series. Photography and performance art have a long history together: artists have often relied on photographs not only as evidence of an activity, but photographic documentation can also function as a kind of visual currency to distribute ideas about time based art-making. One need only to think of the image of Joseph Beuys “explaining art to a dead hare,” or Chris Burden’s crucifixion on a VW Bug to see how photography and performance are inextricably bound in the creation of a kind of anti-celebrity yet heroic aura around the artist. In opposition to the aura of rebellion that inflates so much of performance photography, the Thread series in particular flattens out the performative in service of the pictorial. Eight hundred to 21,000 yards of thread are unspooled like a continuous line, building density, volume, perspective, detail, shadow, texture, and contour. From across the room, one identifies these images as, perhaps, nineteenth-century nature studies and landscape exercises, but on closer inspection we find that our assumptions are incorrect. Our expectations of subject matter and material are confounded: these are photographs that look like drawings but are in fact documents of a durational performance. We view a scene, a pastoral perspective represented in thread, and we are brought to think about an unseen action in which the artist, over a period of days and weeks, unfurled thousands of yards of thin cotton line upon a lightbox, creating an illusion of a traditional pen-and-ink landscape.

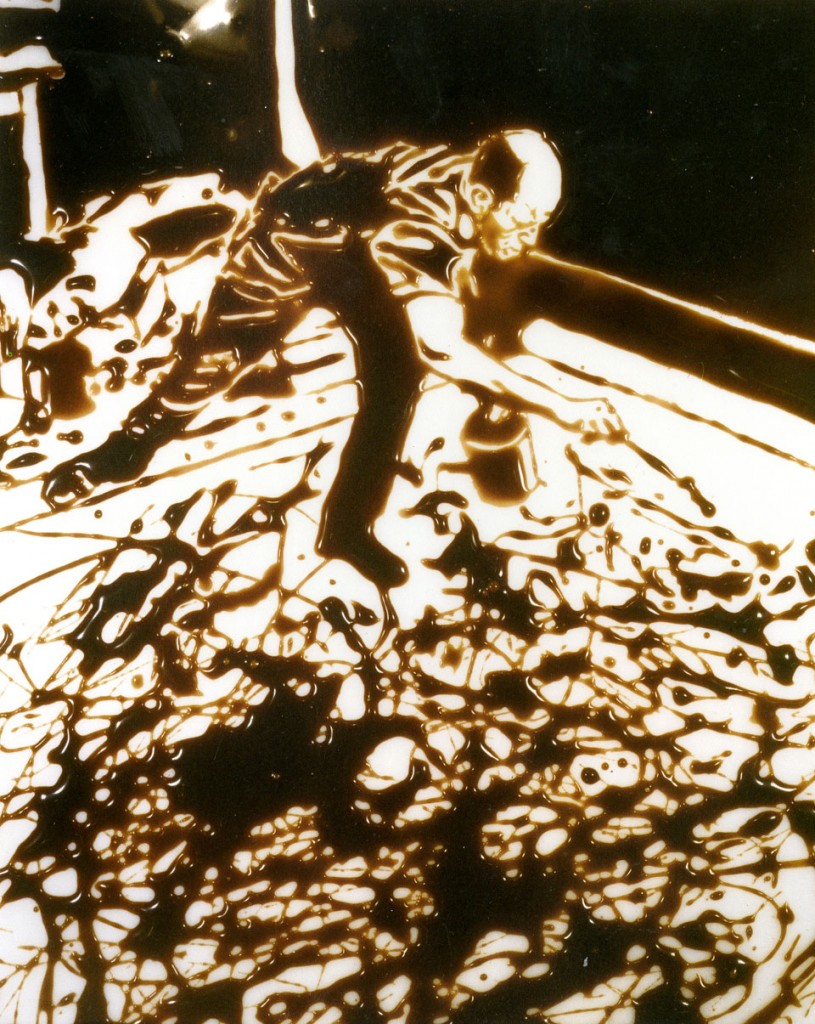

The first image made in the Pictures of Chocolate series was a portrait of Sigmund Freud. As with The Sugar Children, Muniz wanted to increase the sensory palate of his imagery, and was struck by how chocolate in particular seemed to have a seductive power over many people. Freud seemed a natural beginning for a group of images that could be erased with a vigorous slurp of the tongue. Drawing with chocolate (Bosco, actually) proved to be a unique challenge; if the image was not drawn and photographed quickly, the liquid would lose its glossy wetness. It was also necessary for the first time to photograph in color, as the liquid chocolate resembled a filrn-noirish blood when rendered in black-and-white tonalities.

In dripping and glistening chocolate, Muniz has cleverly re-created several images of Hans Namuth’s portraits of Jackson Pollock working in his studio. These images were originally published in Life magazine and exerted tremendous influence on the image of the artist in the popular imagination. These images remain symbols of the artist as a tragic figure heroically struggling with his internal demons, recording the metaphysical battle on the surface of the canvas. Namuth’s photographs have become iconographic documents of painting as existential performance. In Muniz’s revisionist history, although the images are blown up, monumentally forcing the photographs to function on the scale of painting, he gently revises the overblown seriousness of the myth of the rugged male artist spilling his guts onto virginal canvas. Muniz empties the historical image of its stale content, causing us to gleefully respond to the simple wonders of pictures: how one can draw with chocolate, how a photograph can look like a painting, how some things look like other things, which in turn look like still other things.

Muniz reminds us that all pictures are illusory and therefore fundamentally miraculous: seeing is believing. Intellectuals and skeptics can scoff at the gullible masses and their devotions to such apparitions as the Virgin of Guadalupe as it forms in the window condensation of an office building. I, for one, think we should humbly accept miracles between and whenever they are given. Representation is the altar of communication between our internal landscape and the external chaos of things that are not us. When we perceive something, even if it is illusory, we activate the intricate machinations of comparison, and in that process lies the interconnectedness of all things. In the genetic structure of our imagination we intuitively understand that the familiar and the aberrant, the human and the animal, the intimate and the dispersed are variations in a kaleidoscope of forms. Even when we sort out difference, we do so through dialectic of recognition and wonder, thereby creating a correspondence between divine creation and humanity’s humble imitations.

Originally Published in Vik Muniz: Seeing is Believing, Arena Editions, 1998