Two Episodes of Credulity

By Mark Alice Durant

1.

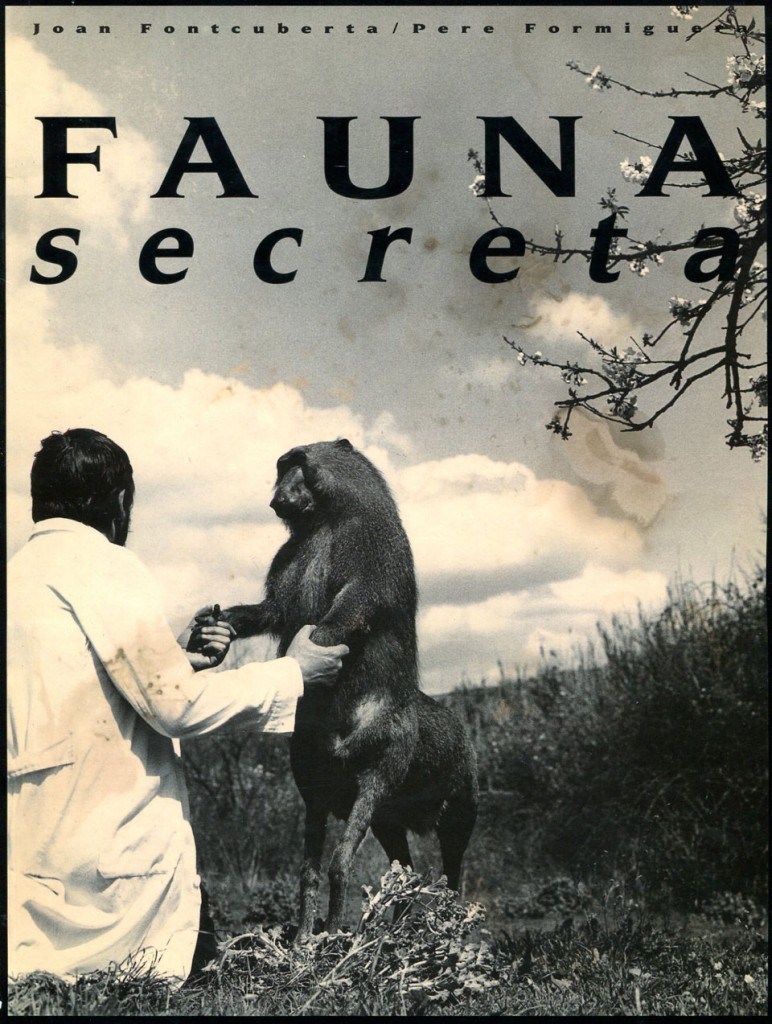

In 1990 in Chicago I attended a lecture given by the Spanish photographer Joan Fontcuberta. He started his presentation by announcing that he was putting his own work aside temporarily to devote his time reassembling the long-lost archive of an early-to-mid 20th century German naturalist named Doctor Amiesenhaufen. According to Fontcuberta, Ameisenhaufen was a bit of a rogue scientist obsessed with mutations in nature, traveling to far corners of the earth investigating any and all legends, myths, and stories of strange beasts. Fontcuberta showed slides of Ameisenhaufen’s notebooks, his laboratory filled with taxidermied phantasms and images of Ameisenhaufen himself in the field interacting with the creatures he was studying.

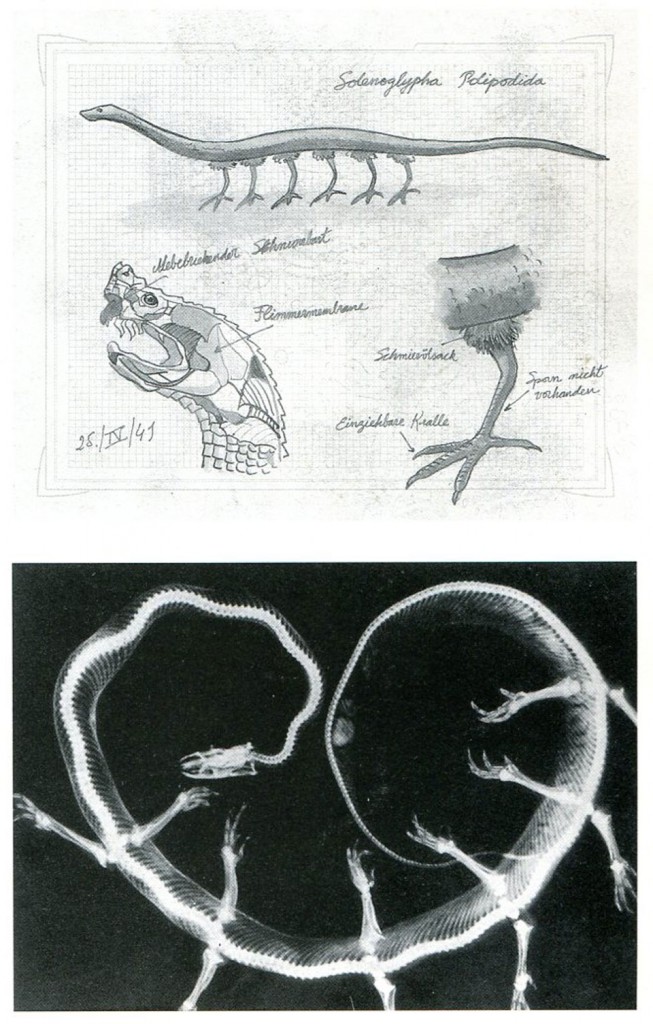

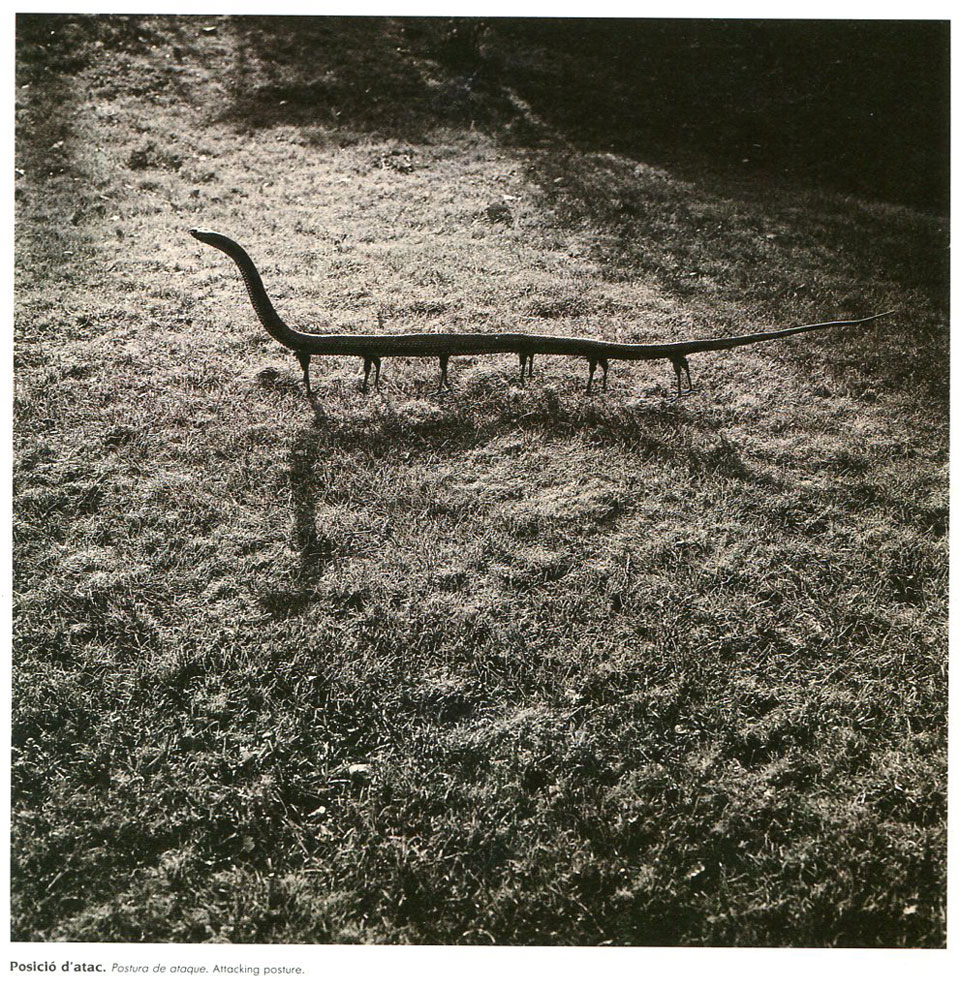

I was enthralled by the accumulating weight of evidentiary archival material: faded photographs, field notes with smudged ink, exquisitely detailed drawings of dissections, x-rays of unusual bone structures, the Latin names Amiesenhaufen gave to newly discovered species, all cohered to suggest that the world was still a strange and surprising place. The feeling of wonder is all too rare, in my experience, and I savored every delightful revelation and shudder of revulsion that these strange and unexpected creatures provoked.

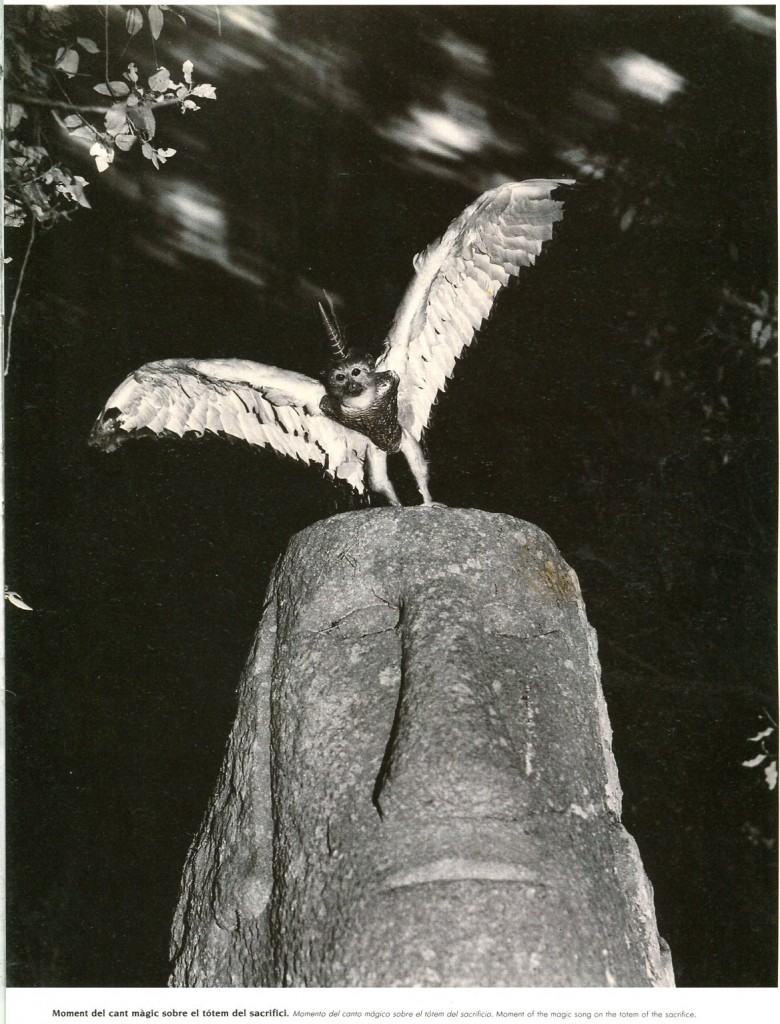

As the lecture progressed, and the animals grew more fantastic, a few laughs and exasperated shouts began to pop up here and there among the audience. I tried to ignore their rudeness and paid closer attention to what Fontcuberta was saying in his thick but charming accent. There was Soleneglypha polipodida a 12-legged snake-like creature found in Tamil Nadu in Southern India. Extremely venomous, it kills for pleasure as well as sustenance, immobilizing its enemies by emitting a high-pitched whistle. Another fabulous specimen Cercopithicus icarocornu was found in the Brazilian Amazon in 1944. It is a simian-looking creature with large functional wings and a unicorn-like horn sprouting from the top of its head that it employs for hunting small mammals. It reminded me of the flying monkeys in the Wizard of Oz, and while I wasn’t convinced there were Easter Island-like stone heads in the Amazon, I was still persuaded by the evidence gathered by Ameisenhaufen and represented and validated by Fontcuberta.

It was almost like a test of mass credulity – how far was one willing to go to believe Fontcuberta’s improbable story? I must say that being the gullible sort – my desire to believe is quite fervent – it was not until Fontcuberta showed an image of a club wielding mollusk – that I finally gave in and understood that Dr. Ameisenhaufen was a complete fabrication. My explosive guttural laugh was a product of both intellectual and physical surprise, as if I had to exorcize an excess of contradictory sensations: outrage at being fooled, and delight at the ornate charade.

2.

On October 15, 2009 I was sitting in my office at the University of Maryland preparing for a class. My Teaching Assistant at the time, Jaimes Mayhew and I were chatting about the usual array of things, art, music, ridiculous celebrities. I rolled over to my desk to Google something we were talking about and as is my habit when I go online, I quickly clicked through a half-dozen news websites to read the headlines: MSNBC, the New York Times, the Baltimore Sun, Huffington Post, the Daily Beast and CNN.

An image of something bright, shiny, round, and metallic flashed on the CNN website. There are certain audio and visual triggers from my adolescence to which I respond like a well-trained dog, practically salivating. Like when the opening notes of a song on the radio lead me to think it might be a Beatles’ song, sending shivers of anticipation not only through by body but across a topography of memories. A second trigger comes from my life-long obsession with UFOs – any roundish object blurrily imaged in the sky will get my full attention in a heartbeat.

CNN was reporting live about a home-made weather balloon racing across the Colorado sky that allegedly had a young boy inside of it. The video footage flipped back and forth from seeing the streaking silver object from below and from a helicopter that was tracking along side it. The orb looked like a crude UFO covered in aluminum foil, a larger version of the dozens of models I had made in my parent’s basement. I was and am a sucker for any narrative involving lost or endangered boys but since having a son of my own, who was three years old at the time, I was a goner. I started yelling and weeping simultaneously. ‘There’s a boy in the balloon high in the sky and they can’t catch him!’

Jaimes hurried over and we looked at each other aghast. Originally from Colorado, Jaimes knew exactly where this was happening. For the next hour we could do nothing else but watch. As is their ‘style’, the CNN reporters were hypothesizing realistic and outlandish theories and possible outcomes for the ill-fated flight.

Emotionally and perceptually, everything in those moments felt suspended, yet moving quickly, as if my consciousness had stopped time in order to examine every aspect of the phenomena while simultaneously accompanying the boy as he sped across the sky in an uncontrolled flying object. The reporters nattered on, the footage switched between viewpoints, police cars and emergency vehicles raced down Colorado roads trying to keep up with the mystery object above them. The graphic banners across the bottom of the image ever reminding us that this was happening ‘LIVE’.

About mid-way through the coverage, another graduate student, filmmaker Kristen Anchor came into my office, both Jaimes and I blurted out the details of what we were watching and without hesitation she declared it a hoax. I was appalled by her lack of compassion, ‘A young boy is trapped in that silver balloon, how will he survive?!” Kristen just shrugged and muttered, ‘We’ll see.’

When the partially deflated balloon finally crashed in an open field, the helicopter camera hovered over as police and EMT workers ran to examine the small compartment supposedly carrying the child. Nothing was found, some of the rescuers turned toward the sky and it was not clear if they were gesturing to God or to the camera. More conjecture followed about possible reports that something falling from the balloon miles back.

I had to pull away from the live coverage to teach my class. I reported the story to my students, not knowing that by then questions were being raised about the authenticity of the event. As everyone knows by this point, the balloon boy was hiding in a box back in the garage of his home. The entire episode was a hoax perpetrated by his narcissistic parents who were obsessed with becoming subjects of a reality TV show.

I couldn’t determine if I was more disappointed or enraged by the deception. I was predictably angry with the idiotic parents and how easily the media was duped. But in spite of my worry for the fate of the balloon boy, experiencing the unexpectedly fantastical was fully transporting. Witnessing it with millions of others simultaneously only heightened the pleasure. I felt like a minor character in Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind, imagining my face lit up in beatific astonishment.

Wonder is a powerful thing. The idea of it fills literature and movies. To experience the boundaries of what we know, to sidle up next to it and feel its lumpy contours is as rare as it is potentially revealing. But is wonder simply a pleasurable side effect of ignorance? Is it a deadly seduction? In Deuteronomy we read: “And the Lord shall smite thee with madness, blindness and astonishment of the heart” This is a powerfully unholy triptych. In the balloon boy incident, all three were at play.

Essay © Mark Alice Durant