To Be and To Last

In Spain, the dead are more alive than the dead of any other country in the world. Frederico Garcia LorcaDemocracia is a two-person collaboration founded in Madrid by Pablo Espana and Ivan Lopez. Their Ser y Durar (To Be and To Last) is an 18-minute immersive cinematic experience presented on three large screens in the Black Box space at the Hirshhorn Museum from October 2012 to September 2013. The basic set-up is straightforward; Democracia filmed a group of 5 red-hooded Traceurs (practitioners of Parkour), performing extraordinary feats of acrobatics bounding across a civil cemetery in Madrid. The film uses super-slow motion, stop action, repetition, frenetic editing techniques and a rhythmic score to expand, lengthen and further dramatize the spectacular performance. At times reminiscent of The Matrix and alternately of a sophisticated Nike commercial, Ser y Durar is both accessible and politically layered.

With origins in French military training, Parkour has become a world wide urban phenomenon in which Traceurs interact with the city as an endless obstacle course to be negotiated with grace, efficiency and creativity. The term traceur has its roots in the concept of tracing, and in that sense, the Traceur is re-mapping the city, traversing urban space without regard to the conventional paths of movement. The sidewalks, streets, walls, bridges, signs, and poles that control the path of the citizenry are transformed in the imagination of the Traceur. One might describe Parkour as tribal; small bands of (usually) young men gather with an attitude that is vaguely oppositional without being openly hostile to society. The Traceur demonstrates a kind of brazen individuality that celebrates freedom while implicitly critiquing complacency.

Superficially understood as a kind of game of daredevilry, Parkour is deeply communal and non-competitive. Like graffiti artists, break-dancers, skaters, and even 1950s street corner doo-wop groups, creative physical intervention enlivens quotidian urban space, proffering gestures of unexpected beauty. When the performer has a kind of outlaw status, an element of subversion sweetens the moment with a hint of minor rebellion. The Traceur is not a flaneur, that urban wanderer so important to early 20th century art and literature. The Traceur is not contemplative or discursive; nor does he act symbolically (at least not in any obvious way), he sees the city only as a labyrinth of obstacles; the function and meaning of architecture are usually irrelevant.

By enlisting 5 young men for Ser y Durar, Democracia appropriates the anarchic athleticism of Parkour to serve their own symbolic agenda. With an editing strategy reminiscent of Vertov’s Man With A Movie Camera, the pace begins slowly, almost as a sequence of still-lives as a day begins. A granite star gradually coheres as the sun rises. We see a series of close up surfaces; lichen on stone, a rusting pole, a few fine threads of a spider web, shadows crossing epitaphs, a lizard scuttles across a pile of bricks. As the music intensifies from an electronic throb to an ominous wash, the shadows of the five Traceurs enter the frame.Their faces nestled in hoodies that are adorned with symbols and mottos echoing early 20th century avant-garde movements such as Constructivism, the young men move in slow-motion through piles of rubble as they gather momentum before scaling the walls of the necropolis. Once inside the cemetery, every aspect of the piece shifts into a higher gear, as the Traceurs begin to run, jump and repel themselves across the landscape of cenotaphs, crypts, headstones and columbarium walls. Militaristic drumming propels the frenetic pace. The gravity defying athleticism is dramatized through the use of the multiple screens that repeat mid-air flips and slow the arcing bodies to a standstill.

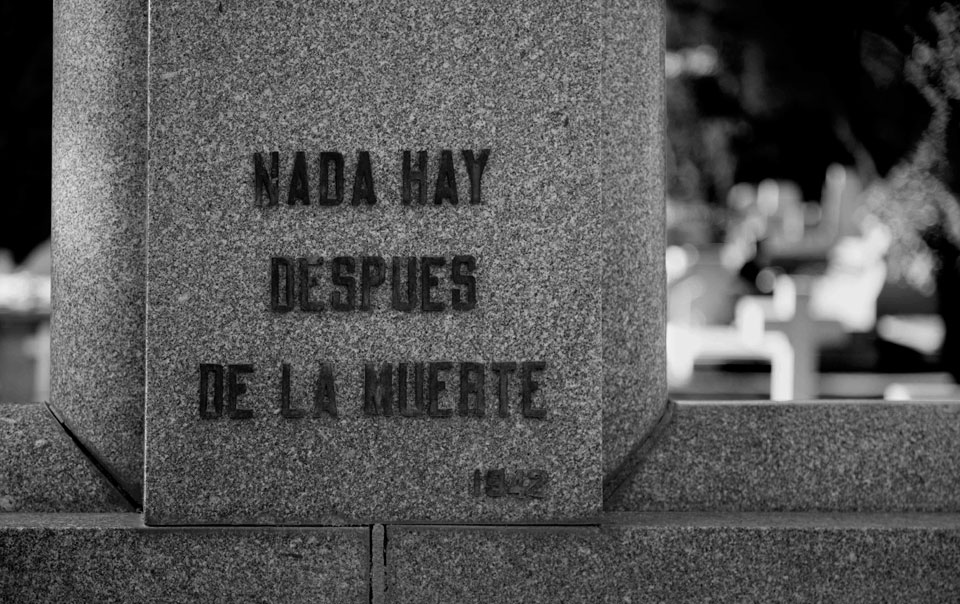

At first glance there is some ambiguity. Are these hooded figures angels or devils, terrorists or artists, athletes or thugs? The Traceurs fly through the cemetery like mischievous red ghosts. Is this an homage to the dead or are they mocking tricksters dancing over the graves of ancestors? Is it disrespectful to indulge life so exuberantly above the rotting corpses? There is something undeniably religious in the display; the viewer sits passively in the dark, mesmerized by the large-scale triptych on which men in ritual garb interact ceremonially with symbolically loaded objects.This being a civil cemetery, and not ground consecrated by the Catholic Church, those buried here were on some level outsiders in Spanish society. In the 19th century the Spanish government decreed that there must be burial place for Jews, socialists, anarchists, artists, and others not aligned with the Catholic faith. It makes me wonder if the afterlife is similarly segregated? Does heaven have ghettos? I suppose that is hell’s purpose.

While almost all societies have gruesome histories of xenophobia and intolerance, between the Inquisition, the expulsion of the Moors in 1492 and the Spanish Civil War, Spain has had more than its share of large-scale violent purges. Because of 20th century signifiers like the red hoodies and the socialist slogans etched in some of the slabs of polished granite, one cannot help but think of the Spanish Civil War. Fought between 1936 and 1939, the Spanish Civil War was a prelude to the horrific large-scale ideological clashes of World War II. In 1939, the Fascist forces led by Francisco Franco succeeded in overthrowing the democratically elected progressive government. Hundreds of thousands of Spanish soldiers, workers, peasants and political activists were killed alongside volunteers from all over the world who had come to fight the good fight defending democracy and the Spanish Republic against the rise of Fascism.

For many reasons the Spanish Republic remains a romantic dream. A (relatively) non-violent socialist revolution crushed in its infancy by the evil Franco, who even Hitler considered a fanatic. Never having the opportunity to devolve into the authoritarianism and ugly failures of the Soviet, Chinese, Cuban or Korean models, the Spanish Republic lives on in the spirited hopes of progressives. While Democracia does not explicitly cite this period in Spanish history, the echoes are unavoidable. And if Ser y Durar were simply a romantic elegy to that extinguished ideal, well, OK, it works, its beautiful, even if a bit facile.I harbor ambivalence about revolutionary gestures / radical conceits in the privileged art world, yet Ser y Durar is potentially revelatory in spite of, or maybe even because of, its slick production values. Combining street fashion, extreme athleticism, sophisticated camerawork and editing, as a spectacle Ser y Durar is seductive and adrenaline pumping equal to any Super Bowl Half Time show. So while the ghosts of the Spanish Republic may be the prevailing spirits, the piece does not feel ruled by nostalgia. Democracia employs the visual language of contemporary sport, the endless replays and slow motion fetishizing of spectacular displays of agility. The figure of the Traceur himself is vibrant, embodying physical and spiritual defiance. He leaps and twirls over headstones and polished slabs; his very being mocks the absurdity and indignity of death.

Are the political and philosophical aspirations of these artists, philosophers and activists buried with their bodies? Is such utopic dreaming also dead? Crucial to Ser y Durar being more than an opposition between the exuberantly alive and the martyred dead is that the Traceur also mocks the living; we whose bodies atrophy while chained to our hand held devices, acquiescent zombies waiting for the latest update. The Traceur is the dream of anarchism modestly manifest. He is self-disciplined, leaderless, and does not accept pre-determined paths. He is all action and little sentiment. He is completely in the moment, negotiating the concrete realities of obstacles and gravity. The Traceur’s movements pose the questions: How do planned spaces control our movements and our imaginations? In what ways do we passively accept conventional paths and thereby enslave ourselves? The well worn groove of the everyday dims in the ecstatic risks of the Traceur. And as such, he challenges social and political complacency as much as gravity and the limits of human mobility.