The Mask is the Meaning

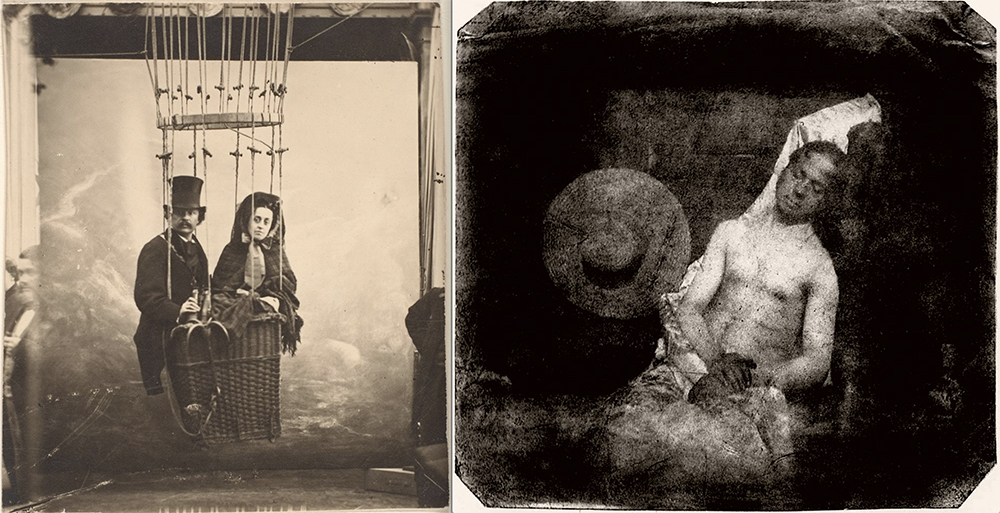

Left, Nadar, self-portrait with his wife Ernestine, in balloon, 1865. Right, Hippolyte Bayard, Self-portrait as Drowned Man, 1840.

As if seeking the clarity of sunlight, the first images appearing out of the murky beginnings of photography made by Niepce, Daguerre, and Fox Talbot, were of window views. This trio of photographic inventors trained their modified camera obscuras toward the light of the outside, a technical necessity that has symbolically and permanently connected photography to the idea of picturesque observation. In the decades before patenting his photographic process, Daguerre was an accomplished theater designer and founder of the Parisian Diorama and certainly knew something about staging narratives, yet this was an association he did not investigate with his new process. The relationship between photography and painting in the 19th century has been richly explored, but the connection between photography and theater, although equally relevant, has received less attention.

Conversely, another, yet often-forgotten, progenitor of photography, Hippolyte Bayard, created the first staged photograph with his direct-positive process — Self Portrait as Drowned Man, to symbolize his thwarted ambitions, when his invention was pre-empted and eclipsed by Daguerre. With bitter humor, Bayard staged and recorded his own death and unwittingly opened the door to another direction photography would take — performance and theatricality. 19th century photographers soon discovered that the camera’s frame naturally created a kind of theatrical space that could be filled with the things of the world, caught unaware, or assembled, choreographed, and carefully lit.

The great French photographer Nadar was also a balloon enthusiast. In addition to his elegant portraits of notable Parisians, he was also the first to make aerial images of the city. One of his favorite studio props was a wicker gondola in which his subjects could climb and be photographed in front of painted backdrops, as if floating serenely above the Pyrenees or the Seine. Always the showman, Nadar photographed himself accessorized with top hat and binoculars tucked into the gondola, an image he hoped would contribute to his legend. Meanwhile, across the English Channel, Julia Margaret Cameron enlisted and directed family, friends, neighbors, and servants, to inhabit her allegorical worlds.

For nearly 200 years, these twin poles of photographic activity — documenting versus directing — the window versus the stage — still define the ways in which photographs are made, seen, and understood. Of course, these twin poles are not mutually exclusive, every photograph, no matter how constructed, is a document of some sort, and documentary imagery involves some bit of staging even if it’s simply the choice of what is gathered inside the frame and what is left out. This tension between document and theatricality has been harnessed by artists throughout the history of the medium to create images that play with assumed categories of fact and fiction, portrait and masquerade. Moreover, while photography catalyzed the democratization of portraiture in terms of who was represented, and promised a more truthful, unmasked portrayal of humanity, unassuming and free of painting’s affect, it also opened up a new arena for creating alter-egos, for playing make believe.

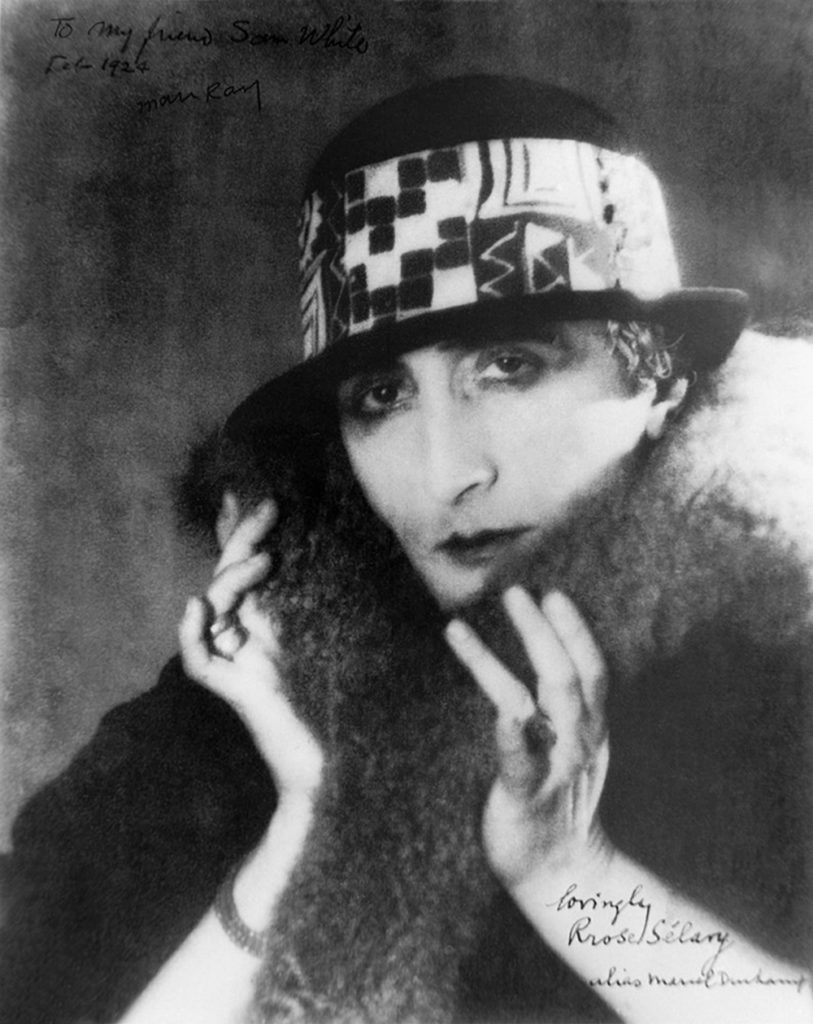

Two early 20th century examples of this sense of play are Marcel Duchamp’s Rrose Selavy and Claude Cahun’s self-portraits. Born in collaboration with Man Ray, Selavy became Duchamp’s alter ego. It was never his intention to ‘pass’ as a middle-age woman, instead Duchamp understood the mercurial power of the photograph to construct an image / identity, and used the portrait of Rrose Selavy to poke fun at the idea of an artist’s persona. Claude Cahun (born Lucy Schwob), cropped her hair and chose a gender-neutral name and created an enormous volume of self-portraits that suggested that identity was not essential but a construction, and therefore, a choice. Her images though, are not simply an exercise in the facileness of identity, there was a deeper questioning of whether in fact an essential self, existed at all. She wrote: “Under this mask, another mask; I will never finish removing all these faces.”

Claude Cahun (Lucy Schwob), left, Self-portrait (reflected image in mirror with chequered jacket), 1927. Right, Self-portrait (full-length masked figure in cloak with masks), 1928.

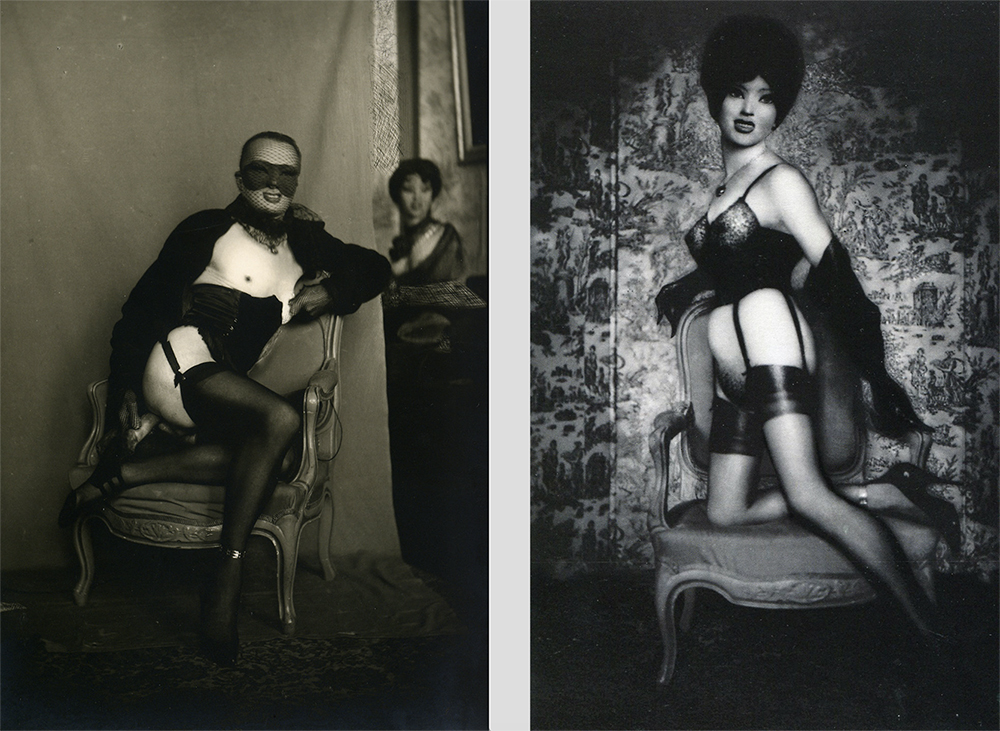

This idea of endless layers of masking is vital to the photographs of Pierre Molinier, a relatively obscure mid-20th century French artist who mixed religious and sexual themes to create garishly theatrical paintings. Despite his unrelenting efforts to associate himself with the post-war Surrealists, his work was too kitschy and perverse even for Andre Breton. When he was sixty-five years old, Molinier began to work a series of photographs for his private erotic pleasure, a series he continued for eleven years until his death, by his own hand, in 1976. Ironically, it was these works, not intended for public display, that earned him some artistic notoriety. Molinier photographed himself, mannequins, friends and acquaintances, both male and female, adorned in high heels, lace stockings, and hand-crafted masks. Through an elaborate process of printing, collaging, airbrushing and re-photographing, Molinier created a secret folio of obsessive, fetishized images of impossible bodies. As if peeking through a keyhole, a dark halo surrounds the seemingly-endless repetition of glowing limbs sheathed in fishnet stockings, phalluses fashioned from silk, and inscrutable smiling masks. A strange aura gathers around Molinier’s images with such a subversive force as to crash into the very foundations of assumptions about sexual identity and cast doubt on our ability to know what is animated and what is inert, what is young or old, what is seduction and what is horror.

The relationship between photography and performance took a significant, if unexpected, turn when in 1950 Hans Namuth, on assignment for Life Magazine, traveled to Long Island to photograph the painter Jackson Pollock. After a nearly a decade of chaotic self-destruction, punctuated by bursts of creative breakthroughs, Pollock had been sober and productive for two years, his personal and professional life had stabilized, and he was now the most famous, if still controversial, painter in America. Namuth was there to document Pollock’s unique process of painting on long scroll-like lengths of canvas unfurled across the floor. Moving around the perimeter, his movements suggesting both ballet and boxing, Pollock attacked the canvas with swirling and looping skeins of paint. Despite his battles with self-destructive insecurity, Pollock had agreed to be photographed by Namuth primarily because he thought the images might burnish his reputation as a swaggering artist whose fearless abandon was heroically evidenced in the complex patterns that clogged his paintings.

After days of being observed and photographed, even before he had seen Namuth’s images, Pollock was sufficiently rattled to uncork the bottle and begin drinking again. A fancy dinner that Pollock’s wife, the artist Lee Krasner, had arranged was ruined when Pollock and Namuth argued ferociously, each calling the other a ‘phony. Pollock expected to be authenticated by photographic observation, to find proof that his own self-performance was convincing, instead he felt fraudulent. Perhaps he experienced what Roland Barthes described as “a sensation of inauthenticity, sometimes of imposture (comparable to certain nightmares.)” Pollock’s extreme self-consciousness led to his ultimate unravelling, he never again put down the bottle, killing himself and a passenger six years later when he drove his car off the road.

After Pollock’s death, the doomed, existential aura that grew around his legend, aided in no small amount by Namuth’s photographs, was ripe for mockery by a younger generation of artists who veered away from such self-important gestures to focus on advertising and popular culture as inspirations. The French artist Yves Klein, audaciously poked fun at Pollock when he created a series of performances in which he dragged naked, pigment-covered women across canvasses in front of invited audiences. His most iconic gesture satirizing the self-mythologizing artist is the photograph Leap into the Void which was consists of two images seamlessly sutured to make a single image in which it appears that Klein is diving from a rooftop to the street below. As Simon Baker has pointed out, in addition to the parodic nature of the image, the importance of Klein’s leap was that it was less of a performance than of creation of a ‘performative photograph,’ an act meant not to be witnessed by an audience, but to be distributed as an image.

The conventional histories of photography seldom consider the body / presence of the photographer and instead emphasize the transparency of the photographic window, as if photographs were produced by disembodied observers. The photographic archive created by conceptual and performance artists, by contrast, has created an of alternative time-line in the narrative of photography which has had wide-ranging influence on succeeding generations. Art students are as likely to be familiar with photographic documentation of Carolee Schneeman’s Interior Scroll as they are with Monet’ haystacks. Echoes of Klein’s Leap into the Void, for example, can be discerned in myriad works from Bruce Nauman’s Failure to Levitate, Josef Beuys’ Levitation in Italy, and Martin Kersels Tossing a Friend, to Lilly McElroy’s project I Throw Myself at Men. While it would be nearly impossible to make a comprehensive list of contemporary artist / photographers whose works have performative elements, it is safe to observe that a significant percentage of contemporary art has been influenced by the photographic record of performative gestures. Dieter Appelt, Jurgen Klauke, Ana and Bernhard Blume, Cindy Sherman, Jimmy DeSana, David Wojnarowicz, Nikki S. Lee, Melanie Manchot, Isabelle Wenzel, Erwin Wurm, to name just a few, create photographs that posit the body not as only a sculptural vehicle but as a presence that can challenge or haunt social space.

With the growing emphasis on site-specific, conceptual, non-objective, and performative works throughout the 1960s and 70s, photography became an increasingly important tool to document the ephemeral. The photograph functioned simultaneously ad evidence that the event did indeed occur and as a kind of valued currency that helped distribute the artist’s ideas and legend. While not every action / gesture was necessarily recorded, from Yoko Ono’s Cut in 1964 to Vito Acconci’s Blindfolded Catching in 1970, it is difficult to imagine a history of performance or conceptual art without the aid of photographic documentation. When Chris Burden was planning his notorious Shoot piece he told a friend, “I will be shot with a rifle at 7:45, I hope to have some good photos.”

Bodies covered in mud and flowers, bleeding arms, bite marks on skin, paper scrolls retrieved from the body’s interior, a paint-caked face muttering to a dead rabbit, there is something of the holy relic in these photographs of performances by Ana Mendieta, Hannah Wilke, Valie Export, Adrian Piper, Marina Abramovic, and their generation. Joseph Beuys was known to pre-visualize his performances, to de-saturate them so that they would work as black and white photographs. Photography served performance not only by capturing the action but by composing the event in a way that could transform the transient to the iconic. As if existing somewhere between portraiture and sculpture, these artists were making works in which their bodies were both subject and object. They understood that the ‘aura’ surrounding their fabled actions was, in part, created by the camera.

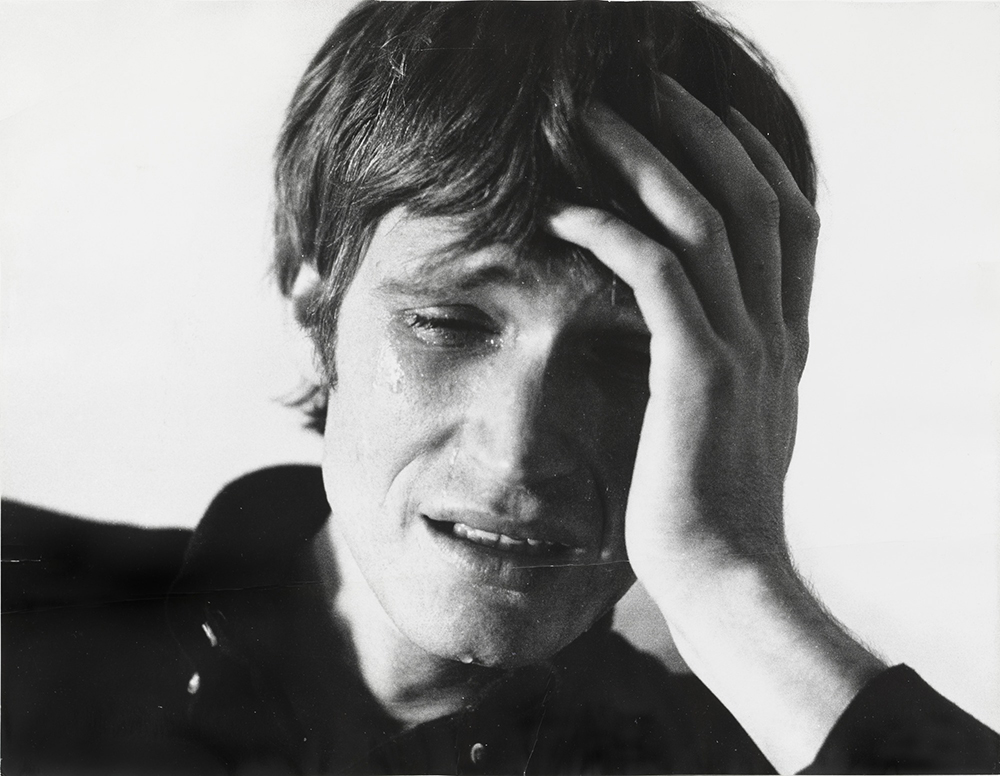

Photography can transform the ordinary into a spectacle, can alchemize the mundane into metaphoric gold. Relying on the paradoxical space that photography creates between the familiar and the distant, Bas Jan Ader, in a very brief five-year career, recorded himself enacting the simplest of gestures such as walking, falling, and crying. Perhaps no other artist has benefited more from the aura generated by the photographic, his brief life and death have been mythologized to an almost absurd level. I’m Too Sad to Tell You was originally a series of photographs and later re-enacted for a short film. Ader’s face crumples in what we assume is private grief, his fingers dig into his eye sockets as if to dam the flow of tears. The image is both obvious and utterly unknowable, relying on photography’s inherent inscrutability to point towards the mystery of another’s internal landscape. His last work was part on an ongoing series titled In Search of the Miraculous, a solo voyage across the Atlantic. Other works in the series are photographs that show Ader, always from behind, wandering around Los Angeles at night, strolling along the highway or disappearing in the dusk by the Pacific. In a final photograph, taken by his wife, we see him piloting the diminutive sail boat toward the vast gray horizon. The capsized boat was found ten months later off the coast of Ireland. Ader’s body was never recovered.

Carrie Mae Weems is usually not thought of as a performance artist, but she employs photography with a performative and rhetorical force in order to think about presence and absence in relationship to black representations in culture. From her early projects such as Ain’t Jokin’ (1987-1988) in which she constructed photographs that embody and literalize racist jokes, and the Kitchen Table Series in which Weems herself poses in a variety of domestic scenes, she has staged imagery that is obviously theatrical yet rings with emotional and political truth. In her 2006 series Roaming, we see Weems, usually dressed in a long black gown, from behind, standing in front of ancient edifices and layered landscapes. Her elegant yet insistent presence suggests a ghost, a goddess, a sentinel, a silent witness. Like an unyielding interrogator, this enigmatic presence confronts history, writ-large, as if to pose the question “What has happened here?”

If Weems casts a questioning gaze over the past, in her new work, Laurie Simmons gives us a glimpse into our not-too-distant future. Over a 40-year career, Simmons has staged miniature and monumental dramas, to explore issues of feminism, domesticity, and the uncanny, while employing all sorts of familiar and strange human surrogates, from doll house figures and ventriloquist dummies to life-like sex dolls. In her recent series, Kigurumi, Dollars, and How We See, Simmons turns to Japanese manga / anime – inspired Cosplay to further blur the line between humans and their escapist fantasies of themselves. Taking her cue from an already fertile sub-culture, Simmons commissioned the fabrication of several Kigurumi characters with enormously exaggerated doll-like eyes, Dayglow-colored hair, and skin- tight latex outfits. As if posing / posting on Facebook or Instagram, the characters, with their ready-made poses and selfies act just like us. Maybe they are, in all of their highly-crafted theatrical superficiality, of us and somehow more than us. Simmons has said of this work, “I wonder about the fuzzy space between who ‘we’ are to ourselves and the ‘we’ that is created, constructed, and expressed using the readily available tools of the 21st century. Aren’t we all playing dress-up in some part of our lives?”

In Camera Lucida Roland Barthes writes, “Photography cannot signify (aim at generality) except by assuming a mask.” Barthes is suggesting that while an individual might hide behind an image, the mask is the meaning, in so far as it can reveal larger truths about history and culture. This paradox in photography, of accepting, rather than seeing behind the assumed mask, is a crucial aspect of all the great portrait photographers from August Sander to Diane Arbus, from Seydou Keita to Richard Avedon, from Nadar to Warhol. This paradox can also be a tool in the hands of the artist / performer who seeks not to reveal the inner life the individual but something more mysterious about the transformation of the familiar into the enigmatic.

This essay originally appeared in FOAM Magazine, Issue #51, Seer /Believer.