Referential Mania

Phenomenal nature shadows him wherever he goes. Clouds in the staring sky transmit to each other, by means of slow signs, incredibly detailed information regarding him. His in- most thoughts are discussed at nightfall, in manual alphabet, by darkly gesticulating trees. Pebbles or stains or sun flecks form patterns representing, in some awful way, messages that he must intercept. Everything is a cipher and of everything he is the theme.

Vladimir Nabokov Symbols and Signs

Certain images strike us, leaving an impression. The why of that can be either obvious or mysterious. In Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes coined two terms to describe the spectrum within which images attract us. The studium is a kind of generalized interest in things; for example, you have been to Paris, love all things Parisian, so any image of Paris will grab your attention. The second term, punctum, is harder to pin down, in Barthes’ understanding the punctum was a surprising and powerful attraction to a particular detail of an image. So you might be leafing through a family photo album and suddenly the light shining on your little brother’s hair in 1973 devastates you. It might be inexplicable why this minor detail among all the other images of your brother has such an immobilizing effect. Barthes employed the term punctum because it suggests a point, a piercing, a wound, through which the image enters us. A visceral entry, not necessarily welcome, through the body as well as the eyes.

As maddeningly vague as Barthes’ dichotomy might be, it remains an evocative approach to contemplate the power of photography. Might there be different terms that describe other ways in which photographs attract us? For example, some images seduce us through a false premise, like an associational lure, we think we see one thing and it turns out to be something else. We may be disappointed, even irritated but also curious about how we were fooled.

The first time I saw a Fred Ressler image I was in MoMA’s bookstore thumbing through monographs and catalogs. I had spent the day wandering the newly renovated and expanded galleries and was feeling like a saturated sponge, I just could not absorb one more piece of art. I picked up Create and Be Recognized, a catalog for an exhibition of ‘Outsider Photography’ by John Turner and Deborah Klochco, and began reading Roger Cardinal’s introductory essay in which he writes: ‘’Not every home in the Western World can boast a collection of amateur watercolors, yet almost any family will possess an album of photographs taken by its members’. He makes distinctions between conventional notions of outsider art, usually drawings, paintings and objects made by untrained artists and characterized by wild, obsessive and/or naïve uses of materials, color, pattern, and perspective, and what might constitute ‘outsider-ness’ in photography, an odd phenomenon especially since virtually everyone has used a camera which is both a complicated mechanism and relatively fool proof.

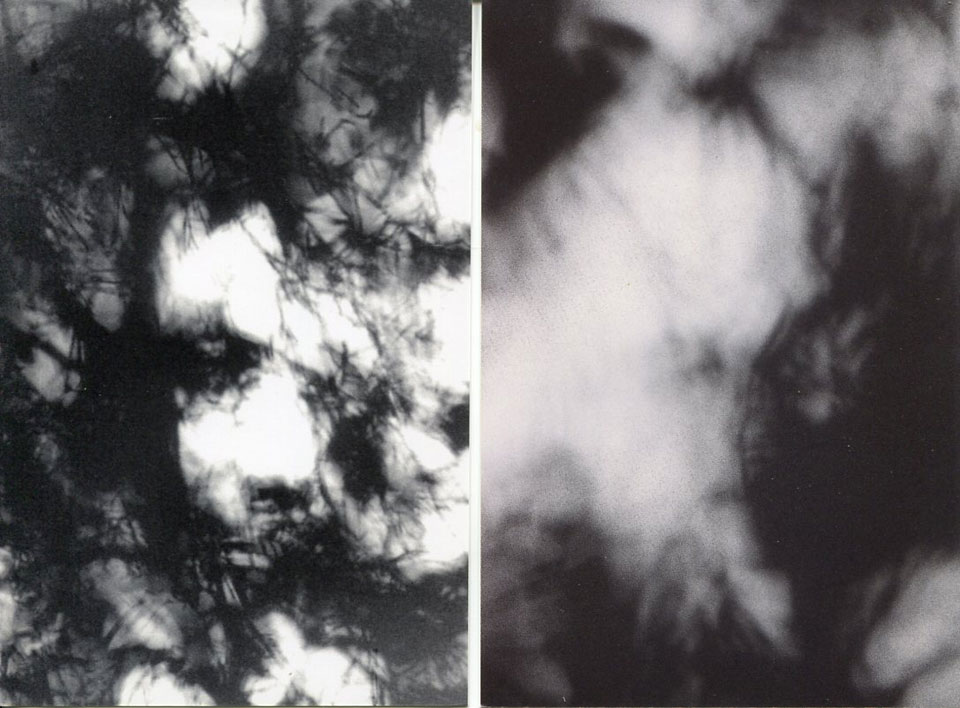

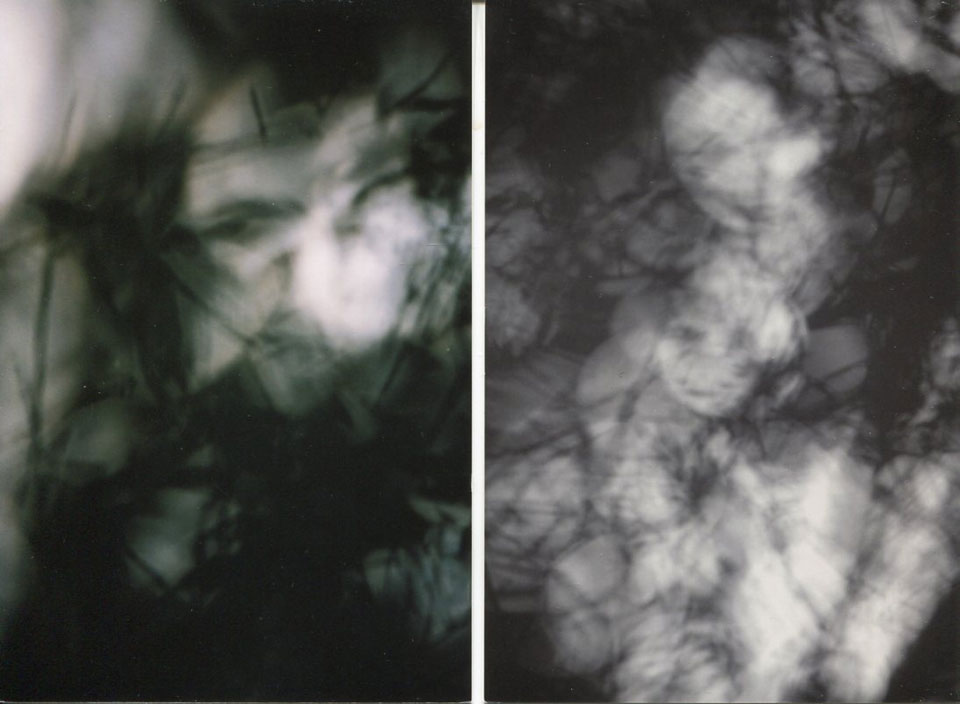

Cardinal briefly mentions Fred Ressler and his images that are formed by sunlight passing through foliage creating recognizable faces in the play of light and shadow. There in the margin was an illustration about the size of a credit card, a puzzle of white and black shapes that seemed to cohere into a portrait of a young female. Ressler titled it: Lila, Native American Princess (daughter). It was as if I had seen nothing else that day, Ressler’s image forced its way into my consciousness, the masterpieces of Impressionism, Cubism and Abstraction that I had dutifully stood in front for hours dissolved like mirages. It’s true that I have had a long interest in Spiritualist Photography of the late 19th and early 20th centuries and am always eager to pore over image of UFOs to determine both authenticity and gape in naïve wonder, but something of a different order was compelling about the Ressler image.

I contacted Roger Cardinal who kindly provided a mailing address for Ressler with whom I began a correspondence that lasted for several months in 2005 leading up to the exhibition that I was co-curating with Jane D. Marsching, titled Blur of the Otherworldly: Art, Technology and the Paranormal. As if to convince me of the authenticity of his images, Ressler generously filled his envelopes with 4×6” prints of his work. He wrote short but intense messages with unanswerable questions such as “If these presences are not real, then why are they appearing to me?” He inscribed the back of the snapshots with the names of his visions, some were religious in nature ‘Mary’ ‘Mother and Child’ and ‘Angel’, some were literary or philosophical ‘No Exit’ ‘Window Watcher’ while others were funny ‘Punker in Lace’, ‘ET’ and ‘Lobster Claw Man and Clara Bow’. We not only included his work in the show, his Leila, Native American Princess graced the cover of the catalog.

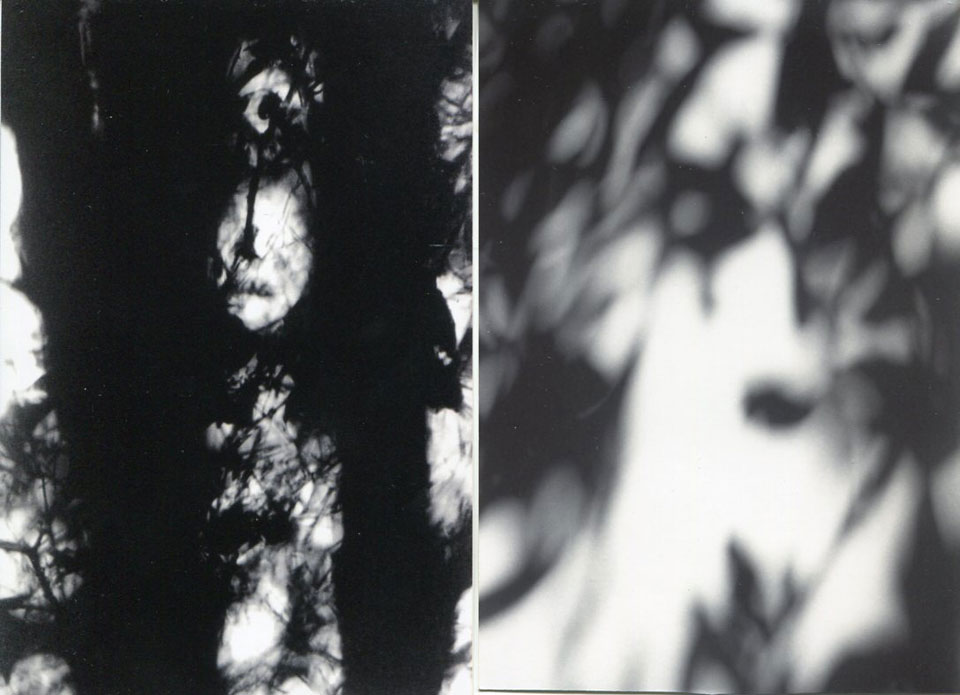

To wander and photograph one’s surroundings is a form of heightened awareness, in this sense, Ressler practices photography as a way to become more sensitive to the furtive mysteries of our world. Ressler, who lives in rural Florida, made most of his pictures over a five-year period in the late 1990s with a point and shoot camera. After accidentally discovering a face in the shadows of one of his photographs, a likeness seemingly hidden in plain view but only revealed through the gathering principles of photography, he began to avidly search for similar apparitions. Later he placed a piece of foam core in the scenes in order to eliminate distracting textures and architectural details. As opposed to 19th c. spirit photographers who self-consciously staged their ghostly images in order to prove and / exploit pre-existing beliefs about the afterlife, Ressler believes this to be a slowly unfolding revelation.

Utilizing the basic material and mechanical characteristics of photography – perspective, framing, focus, and contrast – Ressler transforms these shimmering and elusive apparitions into delicately laced icons. From Bob Dylan to Albert Einstein, from long lost friends to Modigliani’s mistress, Ressler’s images capture elusive visitations both of personal origin and those that represent a larger cultural symbology. What do we ‘see’ when we recognize a shape in a bank of cumulous clouds or the play of light and shadow on a wall? Is this habitual projection merely a genetic predisposition, hard-wired through evolution to help us survive a visually complicated environment? Are we simply playing with the coincidence of infinite variability of form in nature? If this is nature’s Rorschach test, does what we see reveal anything beyond our anthropomorphic imaginations?

Although conscious of the skepticism that might greet his work, Ressler is refreshingly uncynical about the power of revelation in nature and art. He is not a proselytizer but a kind of hunter of radiance and shade, hoping the spirits will reveal themselves through the fundamental binary of photography. He cites the phenomena of pareidolia, a term used to describe our tendency to discern human faces and figures in random patterns. Pareidolia is at work when we see a face in an electrical outlet or see the Virgin Mary in water-stained wall. While pareidolia seems to be programmed into human perception, in exaggerated forms it can be a symptom of apophenia in which the perception of patterns in random phenomena leads to paranoia and delusional thinking. Schizophrenics suffer from apophenia. To travel a bit further down this etymological path, whereas apophenia suggests moving away from knowledge or revelation, the much sought-after experience of epiphany means the opposite, to be in, on or moving toward revelation. Which brings us to a very thorny question: How do we distinguish revelation from delusion?

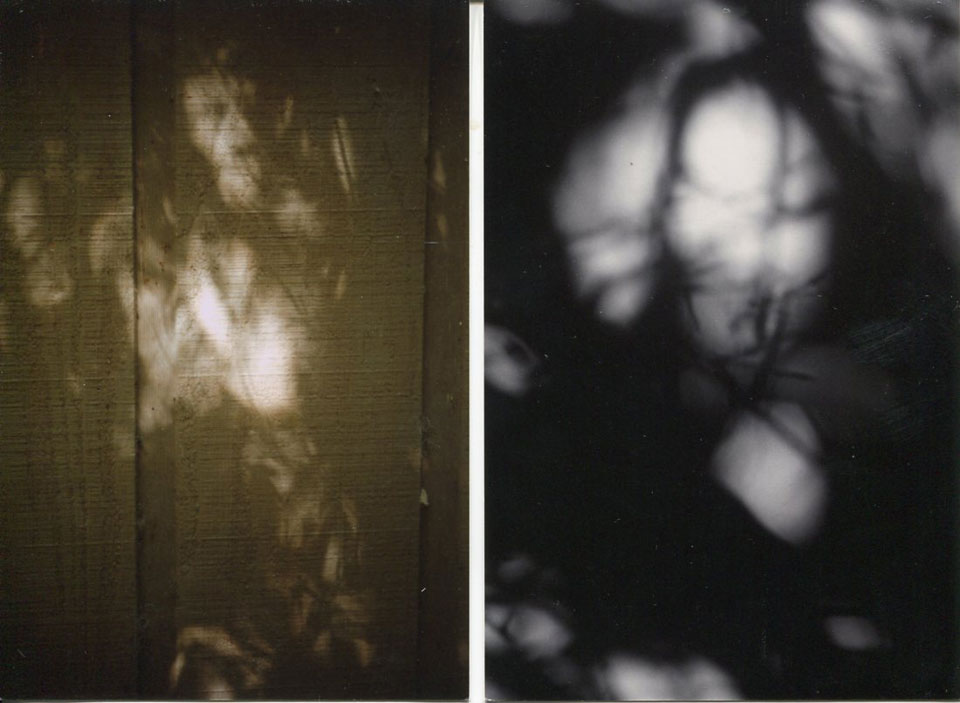

Fred Ressler, Left image, Dan Doloff. Right, Mother and Child (first photo of couple). 6×4″ photographs.

In his short story Symbols and Signs published in 1948, Vladimir Nabokov presents two refugees from Hitler’s Europe now living in a New York tenement. They are older parents of a mentally ill young man who perceives every image and gesture as part of an elaborate conspiracy. Nabokov writes: “He must be always on his guard and devote every minute and module of life to the decoding of the undulation of things”. The parents have read an article describing this behavior as ‘Referential Mania’. Unable to care for him properly he is now institutionalized. As the story opens they are on their way to visit him on his birthday.

Upon arriving at the sanatorium they are told that he has attempted to take his own life, they cannot see him. The story follows them on their long bus and subway rides home, each lost in thoughts filled with bittersweet memories and litanies of regret. Once home they try to establish a sense of normalcy through rituals of shopping, cooking, playing cards and perusing old photographs. Their moods brighten considerably when they resolve to bring their son home. But their merriment is interrupted when the phone rings late at night, not once but twice, by someone dialing the wrong number, a young woman’s voice asking after ‘Charlie’. They are unnerved when, as the story ends, the phone rings a third time.

What do those phone calls mean? Should they answer that third call? And if so, what bad news, because it can only be bad news, will assault their tenuous calm? Mired in uncertainty we realize that Nabokov has tricked us; we are led to feel a sense of dread as we attempt to ascertain the significance of these random misdialed calls. Seeking a revealing pattern, we twitch with apophenia. In Nabokov’s story this question of delusion or revelation is a false binary, as they often co-exist within the same experience. I cannot refute Fred Ressler’s images in the same manner I would an ectoplasm image from the early 20th century, those strange, hysterical and hokey images of cotton oozing from a medium’s orifices. Unlike a supposed UFO image that is most likely a cake pan thrown in the air over the treetops, I cannot prove deception in his shadow plays. Ressler’s images do reveal recognizable patterns, I think I can detect a presence there. Do they signify anything beyond coincidental likeness? Can we acknowledge the images’ significance to the finder / maker without being drawn into the play of meaning ourselves? If we indulge these questions for any length of time we inevitably become referential maniacs ourselves.