Pierre’s Chimera

To be one human creature is to be a legion of mannequins. These mannequins can become animated according to the choice of the individual creature. When the creature steps into the mannequin he immediately believes it to be real and alive and as long as he believes this he is trapped inside the dead image… Every individual gives names to his mannequins and nearly all these names begin with “I am” and are followed by a long stream of lies. from My Mother is a Cow by Leonora Carrington

The French artist Pierre Molinier was born in 1900 and died in 1976 from a self-inflicted gunshot. His suicide was a final performance in front of the mirror in his studio where for a dozen years he enacted and photographed his rituals of erotic self-transformation. I first saw Molinier’s unforgettable pictures in 1983 while a graduate student at the San Francisco Art Institute. My teacher Linda Connor showed me an obscure catalog from the early 1970s. Covered in black linen and embossed with the words, Pierre Molinier, lui-même (a reference to the Surrealist publication, le Surréalisme, Même), the rest of the text was in German including Peter Gorsen’s accompanying essay On Hermaphroditic Surrealism.

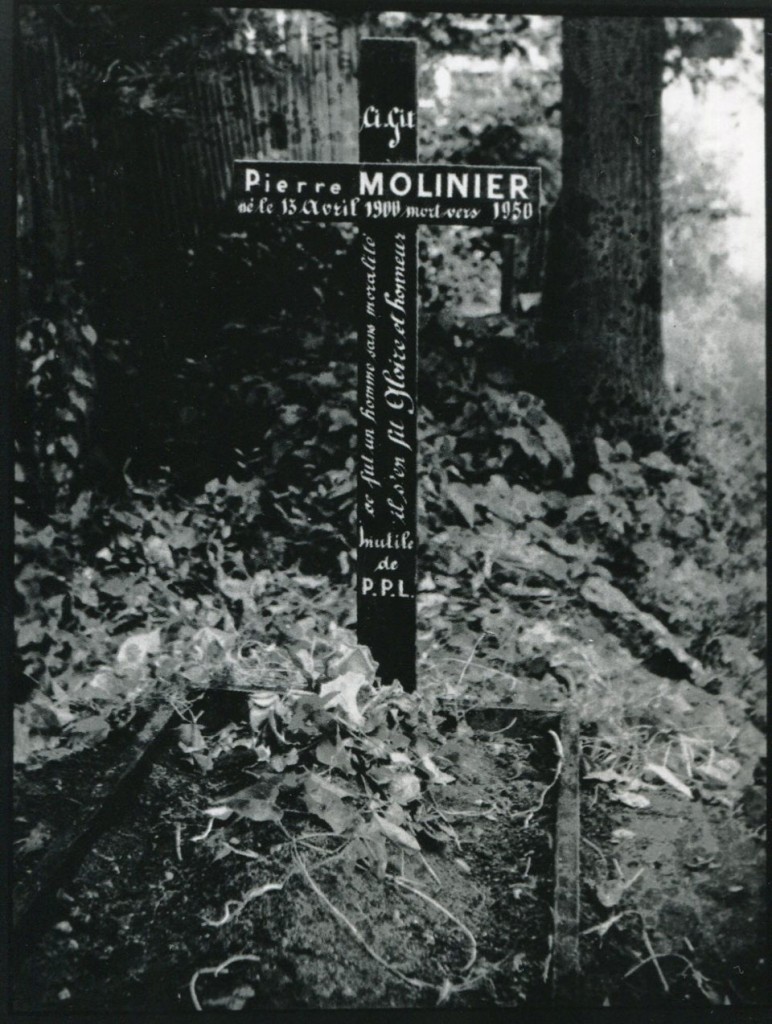

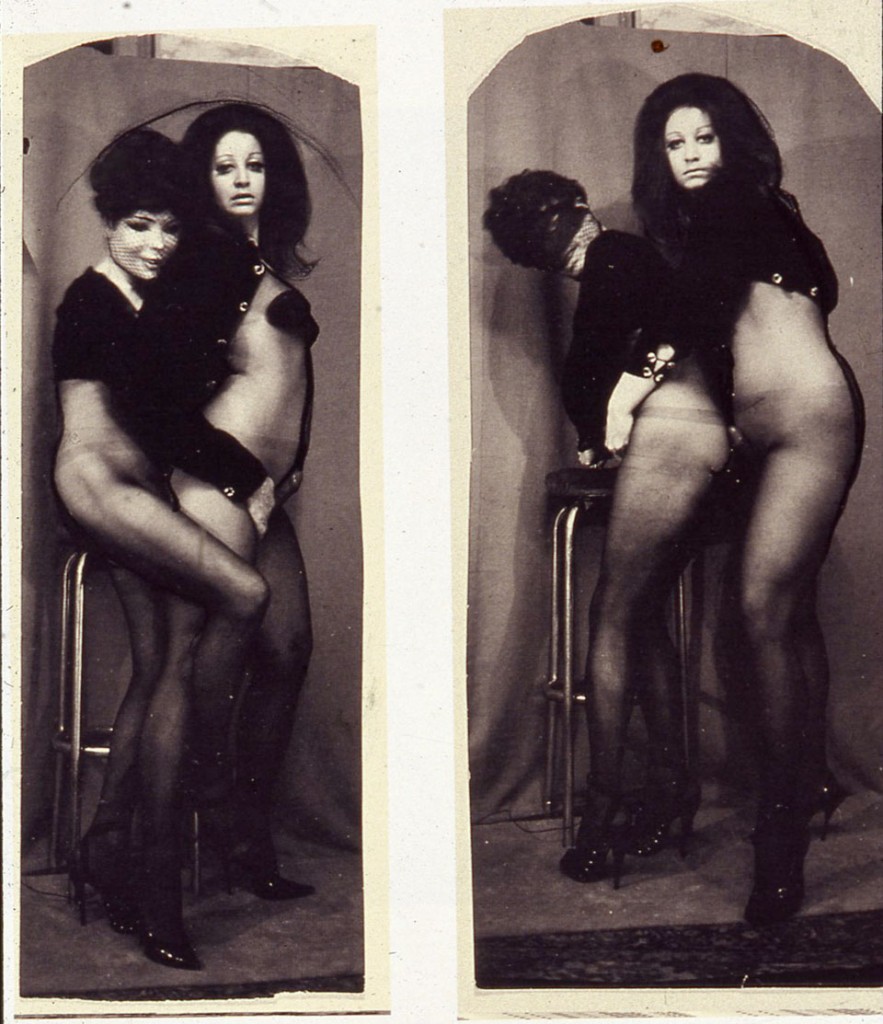

The catalogue itself was like an elegant peep show, black taffeta-like pages separating each new image or sequence of images. The first image depicts a wooden cross grave marker with the name of Molinier carved into the wood. In French, the inscription reads: “Here lies a man without morals.” Transfixed by these photographs, I felt as though I was looking through a keyhole at the end of a dark hallway, the room within lit dimly, perhaps by candlelight and just out of reach. I felt the naughty thrill of stumbling on something not meant for my eyes. In this group of photographs and photomontages, Molinier created hybrids of male and female, mannequin and human, young and old, phallus and fetish, all dimly glowing and vignetted by an enclosing darkness – delicate bubbles of perversion floating like semiotic mutations of the language of identity.

While still a young man, Molinier’s obsessions already began to take form: androgyny, stockinged legs, high heels and obsessive autoeroticism. He was fond of wearing his mother’s and younger sister’s stockings and shoes and became a practicing transvestite by the age of eighteen, which was also the year of his sister’s death. His sister Julienne was, to Molinier, the perfect embodiment of androgyny with her “masculine features, high cheekbones, large fleshly lips,”

As Molinier’s self-mythologizing would have it, when alone with Julienne’s body lying in wake, he photographed her veiled for burial in her gown and silk stockings. After making the exposure, he climbed upon the corpse, caressed her legs and ejaculated on her stomach. Later, on printing the photograph, he wrote: “My love/Its ending.” While determining the truthfulness of the anecdote is impossible, it clearly demonstrates the nexus of obsessions and impulses that were to be the cornerstones of the artist’s final body of work: sex and death, male and female, blasphemy and travesty, performance and its documentation.

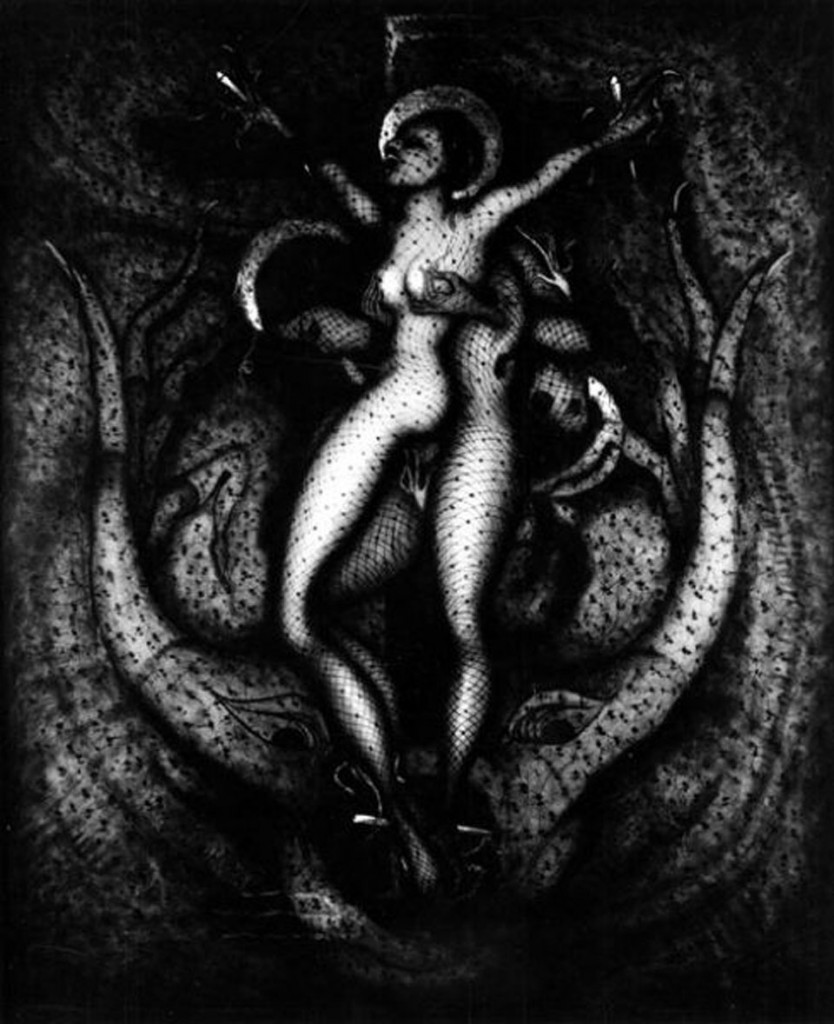

Molinier was essentially a provincial artist. After serving in the French army from 1921 to 1922, he settled in Bordeaux where he lived and worked for most of his life. He considered himself primarily a painter, making photographs for his own erotic pleasure, considering them ancillary to his artistic production. In his early years as an artist, he experimented with previously established styles such as post-impressionism and Symbolism. The influence of Symbolism remains evident in his later paintings and photographs with their melodrama, decadent atmospheres, and mythological motifs of a hybrid bestiary. Artists such as Aubrey Beardsley, Gustave Moreau, and Odilon Redon clearly left their impact.

You got your mother in a whirl, she’s not sure if you’re a boy or a girl. David Bowie, Rebel, Rebel

It was not coincidental that during the period of the late 1960s through the mid-1970s, when Molinier was making his late images, there was a broad resurgence of interest in the Symbolists, accompanied by major European survey exhibitions and the publication of several richly illustrated catalogs. The 1960s counter culture’s interest in alternative structures and visionary/hallucinogenic experiences fostered an explosion of symbols and philosophies that combined eastern and western motifs, the exotic with the urban, the political and the mystical.

In the post-hippie world of rock and roll, the music and images of such androgynous figures as David Bowie (represented on his Diamond Dogs album cover as a chimera), Lou Reed, and the New York Dolls (whose proto-punk sensibility fused with transvestism) resigned in the bohemian underground. Even Mick Jagger, rock and roll’s most notorious heterosexual, had his bisexual androgynous moment in 1972 in the film Performance. If implicit in this turn toward decadent hedonism was the counter culture’s failure to create realistic alternative social structures, a new site of rebellion became the constraints of conventional sexuality.

I search for new perfumes, bigger flowers, unknown pleasures. The Chimera to Flaubert’s St Anthony

Molinier’s mystical, sexual, fetishistic kitsch recalls the Symbolist’s mythical chimera. Most often described as a fire-breathing monster commonly represented with a lion’s head, a goat’s body, and a serpent’s tail, the chimera could be any grotesque creature of the imagination consisting of vivisected body fragments. In genetics, a chimera is defined as an organism that is partly male and partly female. As utilized by the Symbolists, the chimera was a kind of guide or gatekeeper to secret worlds associated with sensuality and visions. The chimera stood at the threshold between the historical and the mythological, between the classical and the modern, between the human and the animal, between the mortal and the divine, between the miraculous and the mundane, between science and the imagination. In a widely read book of the early 1970s about Symbolist art, Dreamers of Decadence, Philippe Jullian described a kind of typology of the chimera:

The mystical chimera… the female pope of secret religions, surrounded by ambiguous angels, flies towards Wagnerian basilicas; with that she is, she conjures up spirits… her sister, the erotic chimera, is a daughter of Baudelaire… sad and even cruel in character; once eroticism had become a priestly function… it gave as much pain as pleasure.

The model of the artist/bohemian versus the bourgeoisie has a particularly French heritage and was often abetted by a vehement anti-Catholicism. Albert Aurier, an important French critic and contemporary champion of Symbolism, penned this simple allegory which concisely illustrates the blasphemous sensibility of his circle: “an evening came since when I have done nothing but weep, grinding my teeth with insatiable longing, an evening of unforeseen madness… the crime of stealing the Madonna’s garter.” The cult of Christ, the sanctity of the Virgin, and the denial of the carnal that so permeate Roman Catholicism became the targets for the French avant-garde’s traditional hostility toward the Church.

The ephemeral, diaphanous, and ultimately vague world imaged and inhabited by the Symbolists was revisited in the 1920s by the surrealists. By this time, the artists were armed with new weapons with which to attack the bourgeoisie: the theory of the unconscious, irony, and a new-found faith in the inherently surreal characteristics of photography. With heroes like the Marquis de Sade, the Surrealists invented a kind of black symbolism – more sexual, more predatory, more agressive – which sharpened what Walter Benjamin has called surrealism’s “bitter, passionate revolt against Catholicism.” In search of “convulsive beauty” (Breton), and “profane illumination” (Benjamin), the Surrealists attempted to reconfigure the almost exclusively female body in accordance with an unconscious landscape of repulsion and desire.

The body is like a sentence that invites dissection in order that its true meaning may be reconstituted in an endless series of anagrams. Hans Bellmer

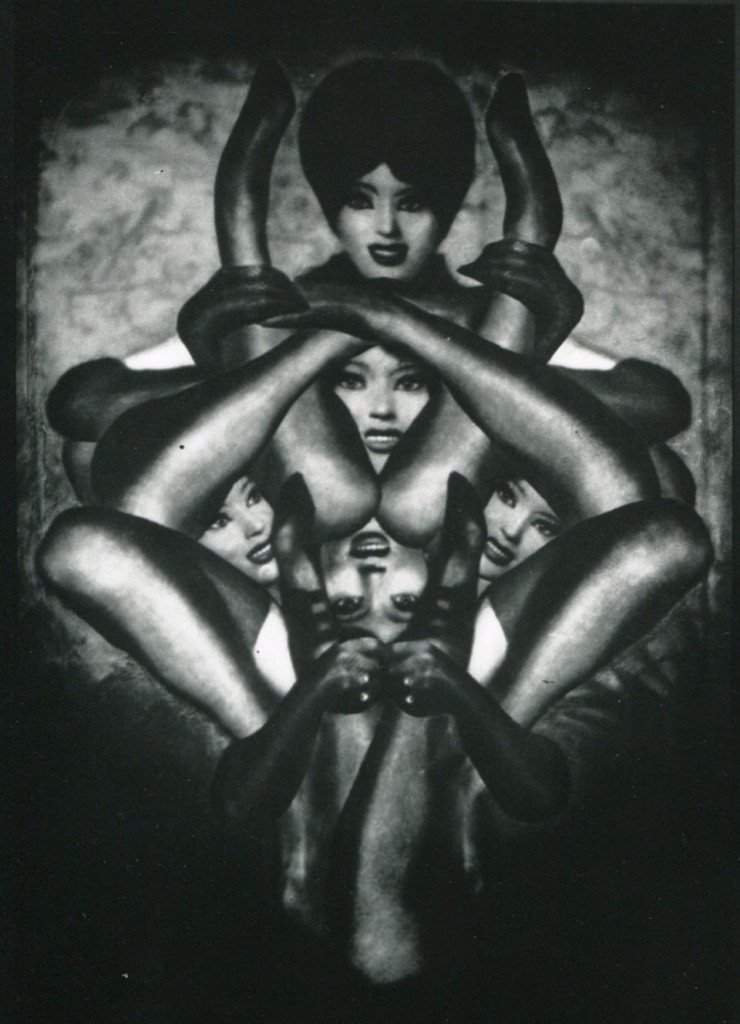

Hans Bellmer’s drawings and photographs of reconfigured dolls are especially relevant as precursors to Molinier’s later experiments with transgressive representations. Bellmer describes using a mirror at the right angles to the body to create a fragmented symmetry of the body and its reflection, what he called the third image, stating “the mirror divides and reproduces at the same time it creates antagonisms, but its movement resolves the contradiction, as a whip does for the top, and goes beyond it to create a third entity.”

The contradictory impulses of montage, that of interruption and reassembly, are both evident in Bellmer’s photographs and Molinier’s photomontages. In Bellmer’s case, the intrinsic seamlessness of the photographic window and the photographic surface serve to make real his puzzle-like reassemblages of a young girl’s body. The presence of the doll is made convincing and palpable by the uninterrupted surface of the photograph. It is as if Bellmer’s dolls appeared before his camera, were found in the world in this manner, and that the photographer merely documented the encounter. This effect contributes to the hallucinogenic and nightmare-like qualities of the images, like stumbling on the aftermath of a grotesque crime in the dark. Additionally, it gives evidence of what Rosalind Krauss and Jane Livingston describe in their ground-breaking catalogue, L’Amour Fou, as “the seeming contradiction between the extravagant productions of the unconscious and the documentary deadpan of the camera.” This, for them, is the reason for photography’s surprising centrality to the surrealist enterprise.

In her essay Surrealism: Fetishism’s Job, Dawn Ades writes that Bellmer’s photographs are haunted by the idea of the “possible body.” “Bellmer claims that desire has its point of departure not in the whole, but in the detail. The body fragment isolated and compulsively repeated also points to male anxiety about lack in the Freudian sense of the fetish.” While there are certain traits that Bellmer’s and Molinier’s works have in common, such as the reconfigured body, the mannequin, the seemingly endless duplication of limbs, and the seamless and evidentiary qualities of the photograph, there are some fundamental differences. The most obvious is that, for Bellmer, the subject of his manipulations is the metaphorical body of the young girl. Bellmer assumes the invisible, yet omnipotent, directorial role, twisting and contorting the object of his obsessions in the attempt to visualize the internal landscape of his own desires.

As for Molinier, while he enlisted occasional collaborators for some of his images, he himself was the primary subject and object of his desire and control. Since Molinier’s photographs were produced by him, of him, and for him, he creates a hermetic trinity of operator, subject and spectator.

In 1955, Molinier contacted André Breton in Paris. Breton was still the ringmaster of the surrealist circle, even as its influence and relevance was in eclipse in the postwar years. Initially, Breton was quite taken with Molinier’s daring images. In them, Breton saw a manifestation of his lifelong mantra: “Beauty should be convulsive, or not at all.” Breton arranged for Molinier’s first Paris exhibition in January 1956. Molinier continued his association with the surrealists until 1965, publishing images and texts in the magazine, le Surréalism, Même. In 1964, Breton collaborated with filmmaker Raymond Borde on an experimental documentary on Molinier and his works.

Molinier continued his association with the surrealist group until the next year when unveiled his collage-painting Oh! Marie… Mere de Dieu in a surrealist exhibition. The painting depicts Molinier as a hermaphroditic Christ on the cross being sodomized with a dildo by Mary Magdalene. Mary, the Mother of God, is squeezing his nipples and sucking his cock. Despite its outrageous humor, evidently he crossed some line even for Breton, who although he fancied himself as the provocateur of the bourgeoisie was quite homophobic.

It is unclear whether Molinier kept his homoerotic inclinations under wraps, so to speak, to remain in Breton’s favor, or whether it was a personal and aesthetic revelation that led him to break with the hetero-myopia that so characterized Breton’s version of surrealism. But it was at the point of Breton’s excommunication that Molinier began his final body of remarkable photographs and photomontages that reach beyond the sometimes kitschy, second-rate post-Symbolist, post-surrealist paintings and drawings that were the primary product of his artistic career.

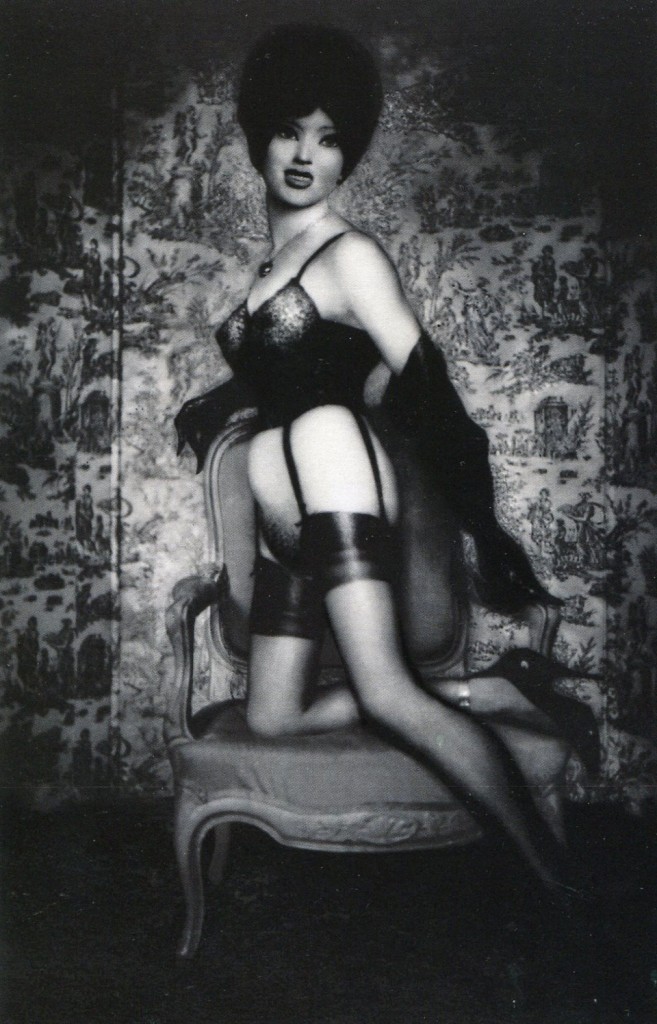

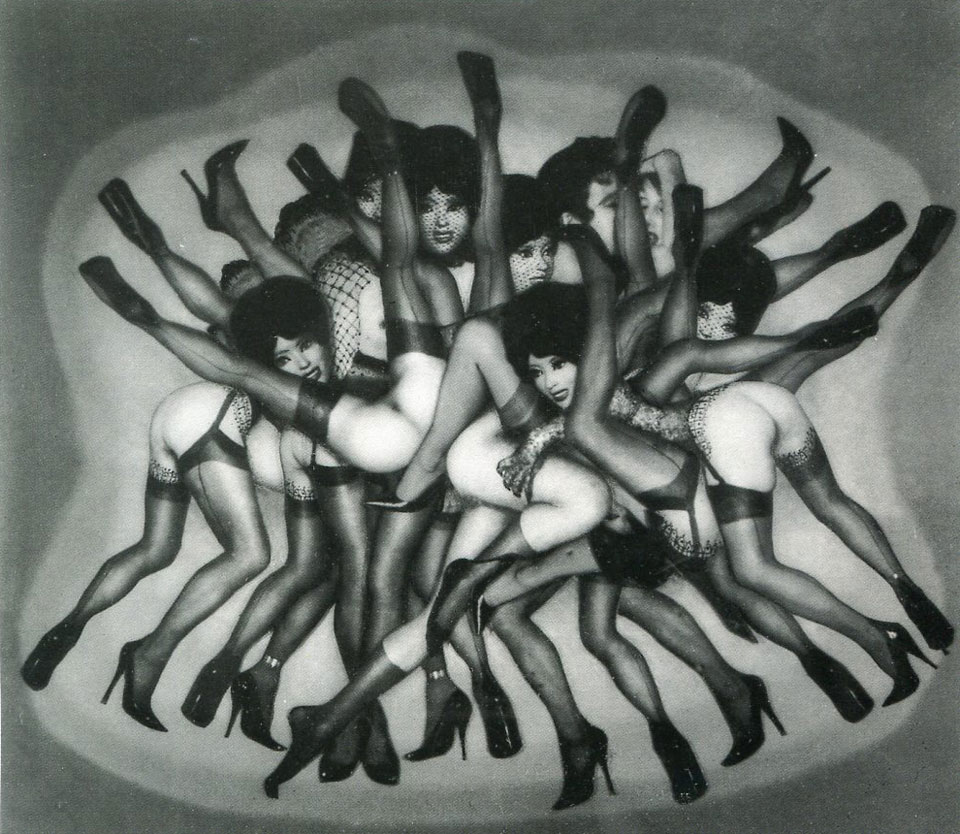

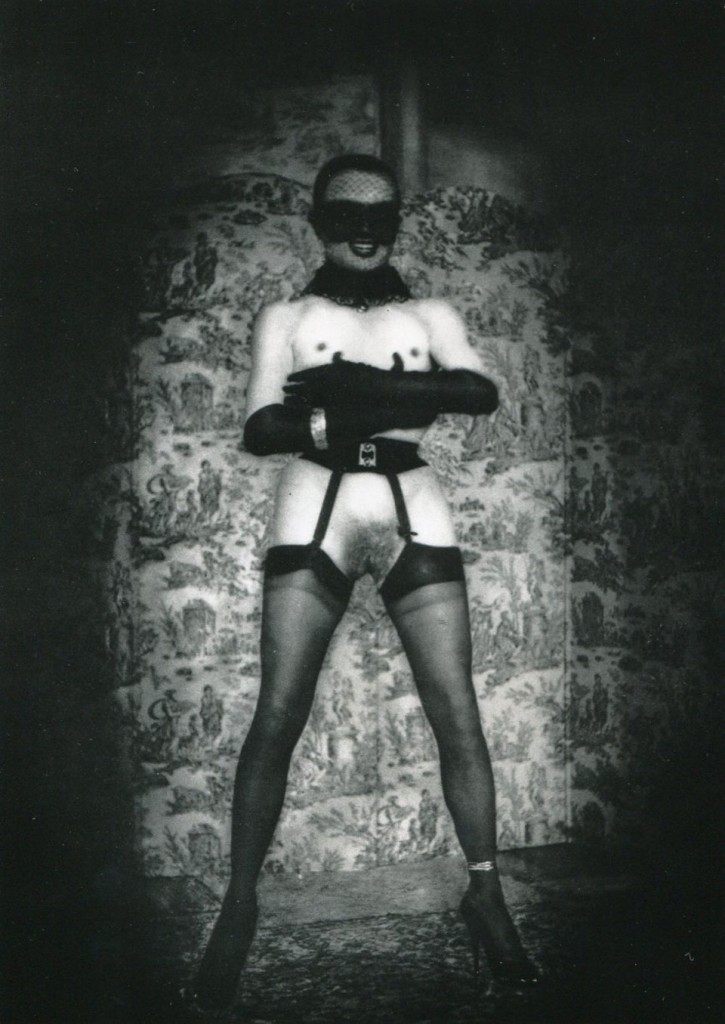

Cumulatively, Molinier’s photographic works display an array of images and objects within his studio: paintings, drawings, collages, fetish objects, godemiches (dildos), masks, high heels, stockings, and customized furniture that serves as props for his photographic tableaux and erotic performances. By his own declarations, Molinier wanted to attain a permanent state of multiple perversion. Aided by extensive airbrushing and montage techniques, Molinier achieved a kind of self-shattering, self expanding, fantasy – a stategic travesty of manhood, a hybrid of male and female, animate and inanimate – a new creature of simultaneous genders. Molinier’s liminal creature, a twentieth-century chimera, stands erect in his high heels at the threshold leading from subversion to submission.

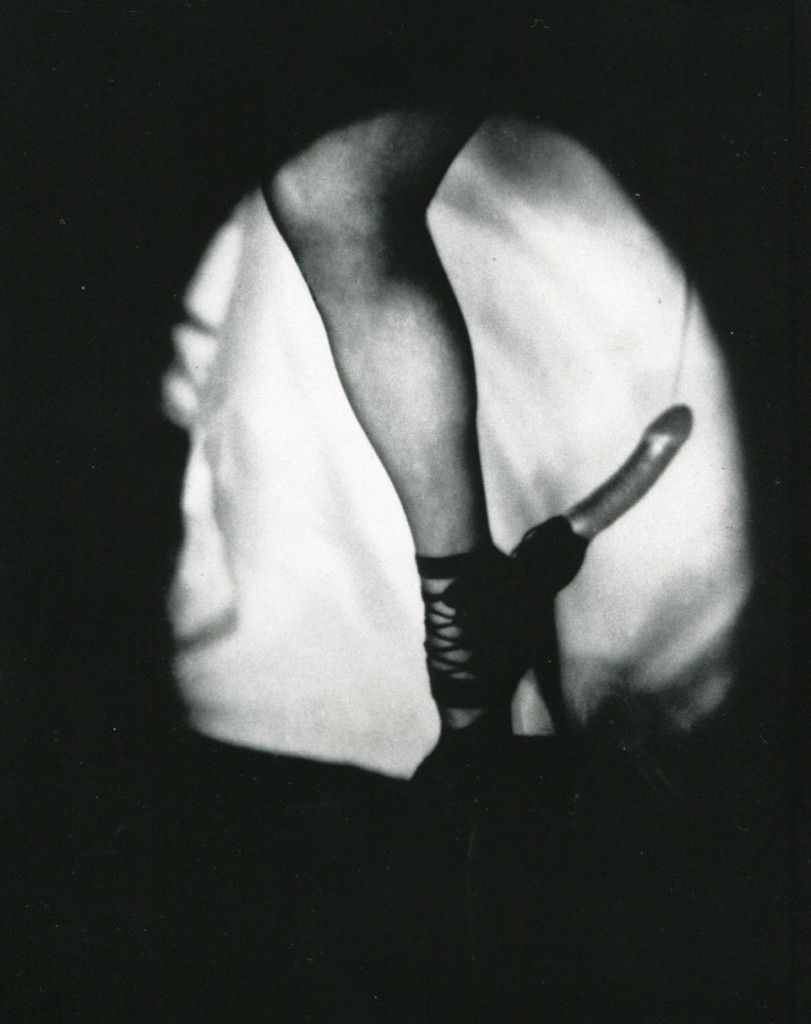

Mon fétiche des jambes is perhaps the most compressed and reductive image of Molinier’s constellations of symbols, objects, and fetishes. In a dramatically vignetted tableau, a stockinged leg is shown from the knee down. The foot is wearing an extremely arched high-heeled shoe that seems to be bound to it by multiple leather straps. Extending from and attached to the heel is a sleek and erect phallic form, one of the artist’s self-constructed godemiches. From compressed silk covered by a prophylactic, Molinier fabricated hundreds of these dildos of various shapes, sizes, and methods for attachment. In this particular configuration, the godemiche could easily be brought up to the anus simply by fully bending back the knee. Molinier’s solution for attaining true androgyny was to be both the giver and receiver of penetration. For Molinier, the phallus becomes both symbolically and actively the agent of transformation, a literal and figurative magic wand.

The doll was so utterly devoid of imagination that what we imaging for it was inexhaustible. Rainer Maria Rilke

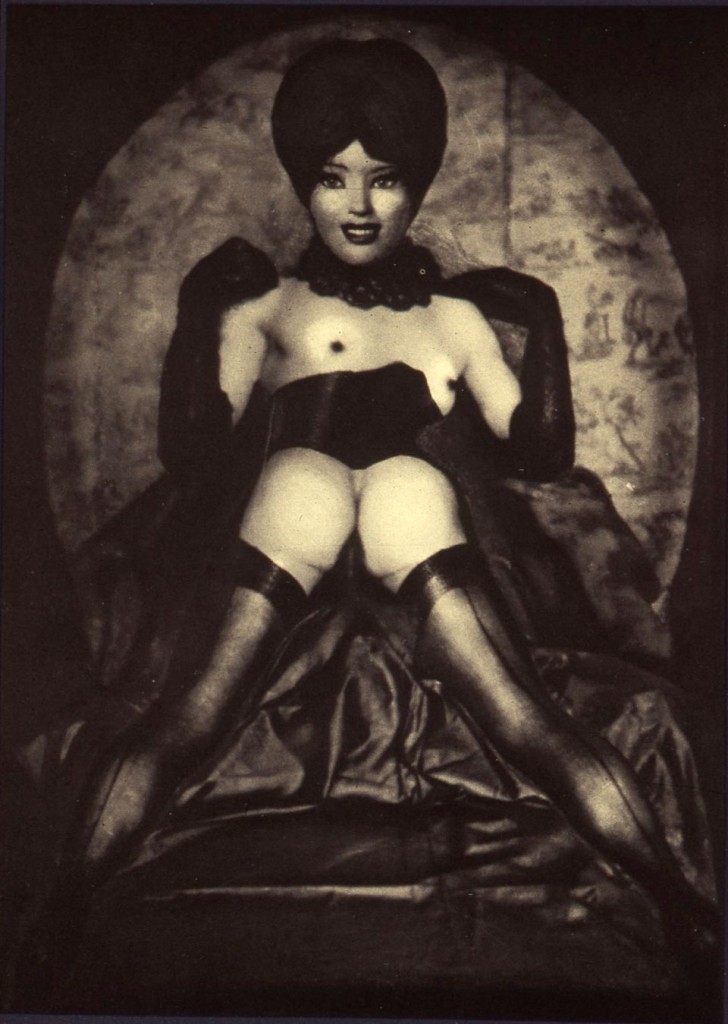

In Torso II, a perfect keyhole effect is created by Molinier’s vignetting. A smiling face atop a body of impossible configuration looks at the viewer invitingly. Are the arms lifted in a gesture of surprise or beckoning? Perhaps s/he is the barker for this carnival of sex acts and freak shows. This figure is unashamed, its face a picture of painted innocence, young and girlish – but finally, an impenetrable mask. The torso is contorted or reassembled so that the breast, buttocks, and face are aligned, overturning one of human anatomy’s basic oppositions, that of front and back. Gorsen writes, “the most important arena for acts of travesty is the female face… ambiguity always arises from self-transformation, from feminizing and rejuvenating an essentially negative connoted, otherwise male-only face.”

It is important to remember that these photographs were made during the last decade of Molinier’s life. He was in his late sixties, and his self-transformations occurred not only at the frontier of gender but also in the face of mortality, of aging and the loss of vitality. What is that face, that masked expression, that frozen smile? Is this the face of rapture, or is this the face of absence, of death? Or, is it simply an attempt to mask the specificity of the aging male physiognomy?

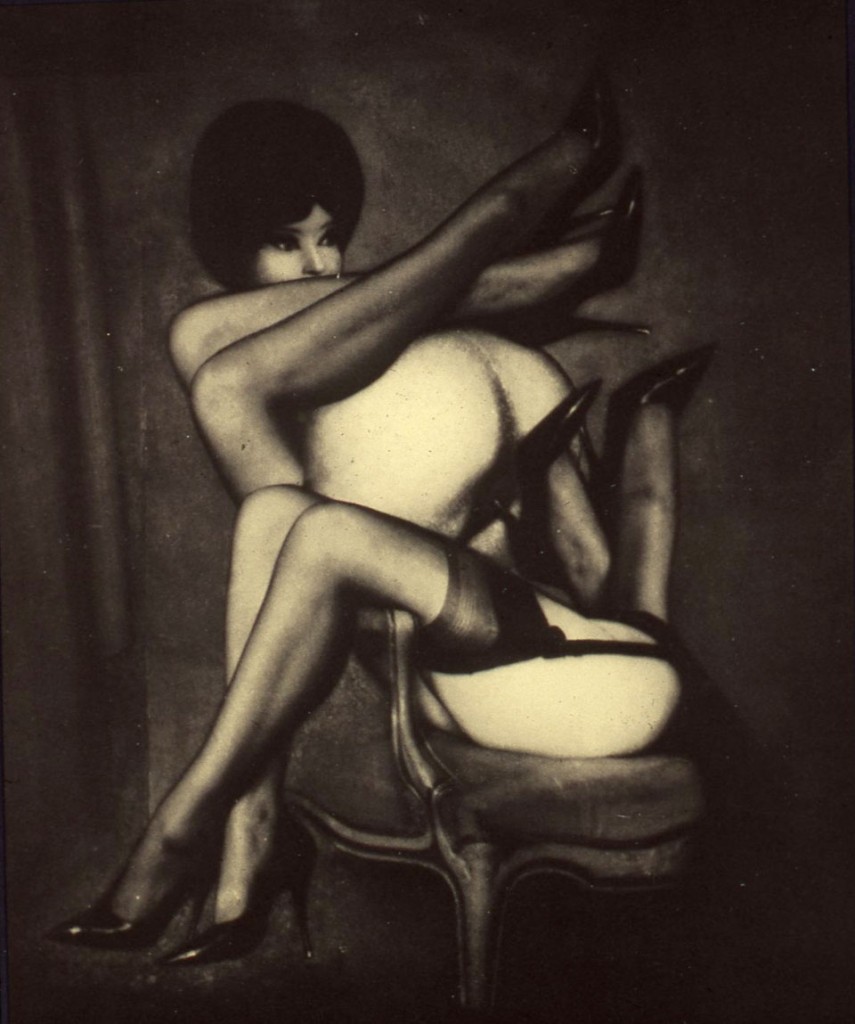

Lenah-Hanel contains three pairs of intertwining legs which spring from two sets of buttocks; a hyper-feminine face looms over this landscape of orgiastic dismemberment. In addition to doll and mannequin fragments, Molinier would often invite his male and female intimates to pose for use in his montages. His most beloved collaborator and model was Hanel Koeck, a German art student whom he met in 1967 when she was in her early twenties and he was sixty-seven. Koeck became the embodiment of Molinier’s androgynous ideal, replacing his long-dead sister. She was also involved with the Viennese Actionists, and in 1969, she re-enacted Molinier’s infamous painting, Oh! Marie… Mère de Dieu, in Herman Nitsch’s 31st Action, having herself crucified and sodomized. Acting out alone or in concert with each other and with dolls, Molinier and Koeck created a series of sexual tableaux and, in a magical transfer of youthful vitality and sensuality as embodied in the fragmentary icon of the photograph, Molinier was able to create an image of youthful androgyny that was no longer possible in his life.

In Self-portrait with Fetish Items, Chaman I, Molinier or his surrogate stands erect and alone, a backlit hermaphroditic figure in high heels, stockings, garter belt, corset, necklace and face mask. The shadowy face appears to be smiling, its eyes resembling flickering flames, cat-like and mischievous. Breasts and phallus exuberantly point upward, and the skin that peeks out from behind the silk, lace and fishnet is all aglow with a satanic shimmer. The hybridization of signifiers is clear, the figure literally stands at the threshold, parting the theatrical curtain with an aggressive flourish and without a hint of furtiveness; this image could function as Molinier’s manifesto. The aging male body attempts to rejuvenate itself through a shamanistic ritual crossover – not into the feminine, but into the netherworld between male and female. This youthful figure is the lead character in Molinier’s ritual theater of transgression, the master/mistress of ceremonies, the man/woman behind the curtain, the painted puppeteer of between-ness.

Molinier’s efforts at transgression and his obsessive attempts to rejuvenate himself not only rattle the windows of what Laura Kipnis has called the “prison-house of binary gender role assignment,” but simultaneously call into being the resurrection of his female doppelgänger, blessed or cursed with a Dorian-Gray-like youthfulness. Visually redundant, but hypnotically repeated, Molinier’s iconography orbits the twin suns of Eros and Thanatos, the burning brightness of desire and the black hole of extinction. Molinier’s chimera, his hermaphrodite, his perfect androgyne, his liminal alter-ego flits in and out of the gates of our various prison-houses and, with each passage, there is a momentary shiver – like the click of the shutter upon release, like the orgasm that is all too brief.

A very different version of this essay originally appeared in The Passionate Camera: Photography and Bodies of Desire, edited by Deborah Bright, Routledge, 1998