Peter Hujar’s Photographic Truth

If asked to name a New York photographer in the 1970s and ‘80s, who employed a medium-format camera to make elegant black-and-white portraits and homoerotic figure studies, more than likely you would think of Robert Mapplethorpe. This is not surprising, since Mapplethorpe achieved meteoric success and celebrity in his lifetime. Yet Peter Hujar was there first, making intensely intimate and exacting photographs of lovers, friends, and artistic heroes for more than a decade before Mapplethorpe picked up a camera. Hujar and Mapplethorpe inevitably knew each other and everyone in the downtown scene, it seems, knew them. They traveled, at least initially, in similar social circles, and photographed many of the same people. So pervasive was their influence and reputations that the photographer Josef Astor recalls that when he moved to New York in the late 1970s as young, gay, aspiring photographer, it was expected that he choose allegiance between the Robert Mapplethorpe or Peter Hujar camps. Despite their commonalities, they created very distinct bodies of work, and their rivalry was not always friendly. Hujar considered Mapplethorpe’s images too calculated and sanitized, dismissing the work by observing, “Well, it looks like art.”

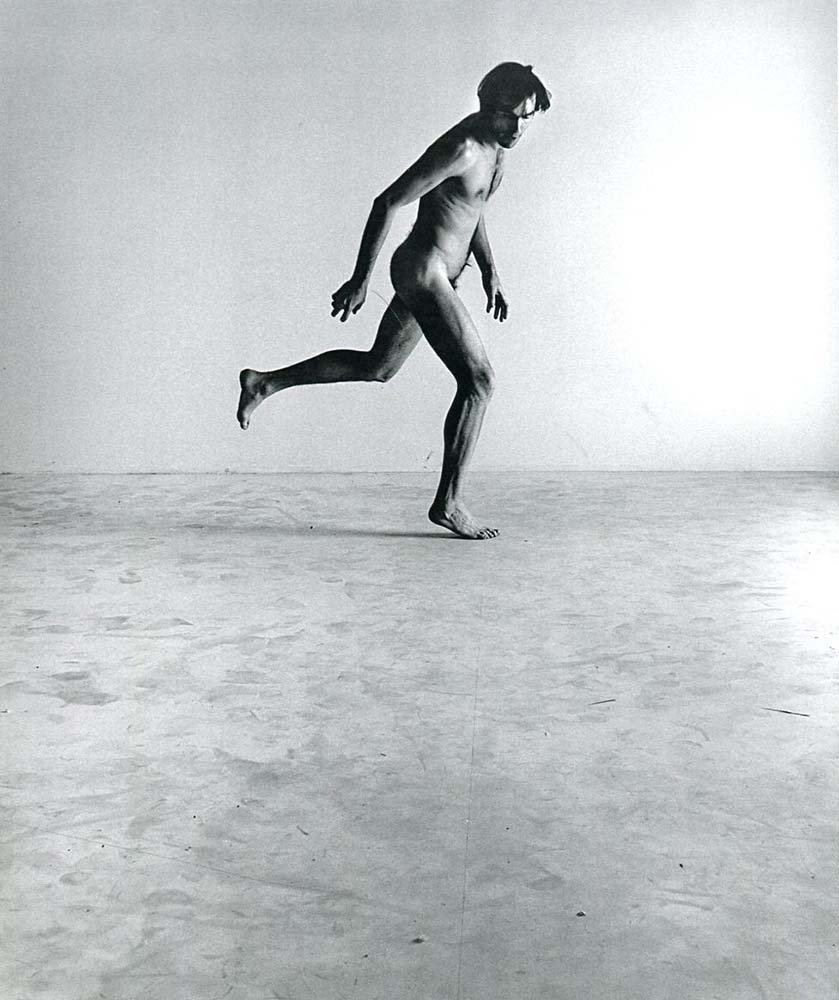

Born in 1934, an only child of a single mom, Hujar was shuffled between New Jersey and Manhattan, finally leaving home to live on his own at 16. In high school, one teacher observed that he was “only interested in photo.” Like many young people with limited exposure to art, he found visual access to a world of creativity and fantasy in fashion magazines. From the mid- 1950s through the mid-1960s, Hujar worked in a variety of photography studios, traveled extensively, and began building a network of artist friends and lovers. In 1967, in what proved to be a personal and professional turning point, Hujar was accepted into a Masters Workshop with Richard Avedon and Marvin Israel. For his application, he made a series of self-portraits while running naked in front of a white backdrop. With echoes of Eadweard Muybridge and influenced by recent encounters with Yvonne Rainer’s Judson Dance Theater, the photographs have a coolness and raw physicality that hint at some of the qualities that characterized his later work.

After the Avedon workshop, Hujar opened his own studio and was awarded numerous assignments from Harper’s Bazaar and GQ. Despite these professional opportunities, he chafed at all that what was required to run a successful studio and yearned to pursue his own photographic interests unimpeded. The classic tug of war between financial need and artistic freedom produced an underlying tension that colored many of his professional and personal interactions. Throughout the 1970s Hujar photographed many artists and writers, including William S. Burroughs, John Waters, Susan Sontag, Andy Warhol, Candy Darling, Yvonne Rainer, and Fran Lebowitz. As his collection of portraits grew, he conceived of a project in which he would pair the portraits with a series of images of the mummified dead that he had made in the Palermo Catacombs in southern Italy. His first book, Portraits in Life and Death, was released in 1976 and featured an essay by Sontag in which she wrote:

Peter Hujar knows that portraits in life are always, also, portraits in death. I am moved by the purity and delicacy of his intentions. If a free human being can afford to think of nothing less than death, then these memento mori can exorcise morbidity as effectively as they evoke its sweet poetry and its panic.

Hujar’s portrait of Sontag from 1975 was taken two years before she published On Photography, her unprecedented cultural critique of photography’s influence on modern society. The image shows her reclining on her back with her hands clasped behind her head. The room is barren, cold, monastic. The first few wisps of what would become her trademark gray streak are gathering in her dark mane. It is a quiet image, contemplative, yet it hints at an active inner life. Sontag appears to be staring up at the ceiling, lost in reverie, but it is unlikely she is unaware of the camera. She must perform the image of Sontag while perhaps searching for the exact phrasing for her book’s opening sentences, “Humankind lingers unregenerately in Plato’s Cave, still reveling, its age-old habit, in mere images of the truth.”

What was Hujar’s truth, his photographic truth? Hujar understood and utilized photography’s tension between document and theatricality. In the act of photographing there is a performance, not only on the part of the subject, but for the photographer as well. For Hujar, to photograph was a balancing act between fierce observation and manifesting his devotion. As Jennifer Quick observes in her essay for the catalogue, This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s, “While Arbus and Mapplethorpe are known for their detached postures, Hujar’s silent, tacit presence pervades his work. Like Avedon, Hujar was the instigator of the performances captured in his portraits, as much as a director as a photographer.” That Hujar is considered in the same company of Avedon, Arbus, and Mapplethorpe, reminds us that the retrospective Speed of Life is long overdue.

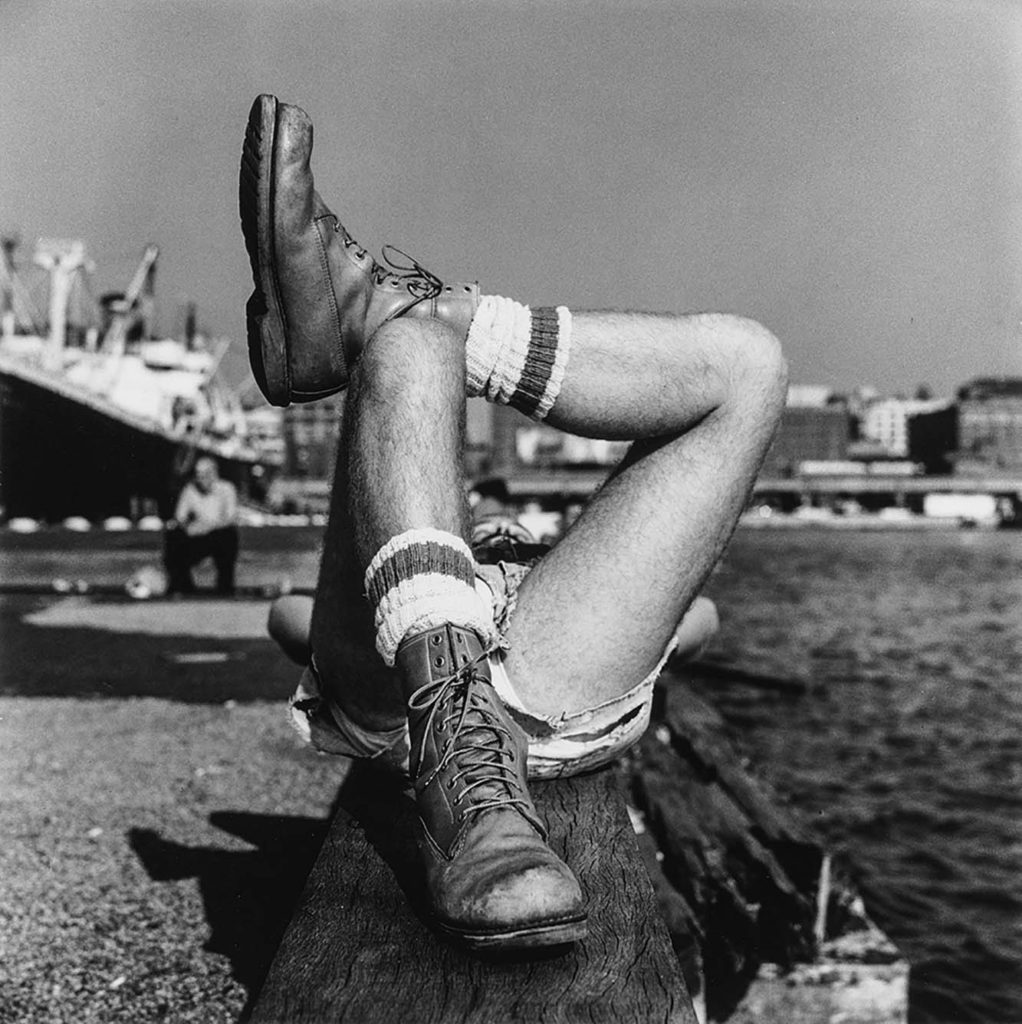

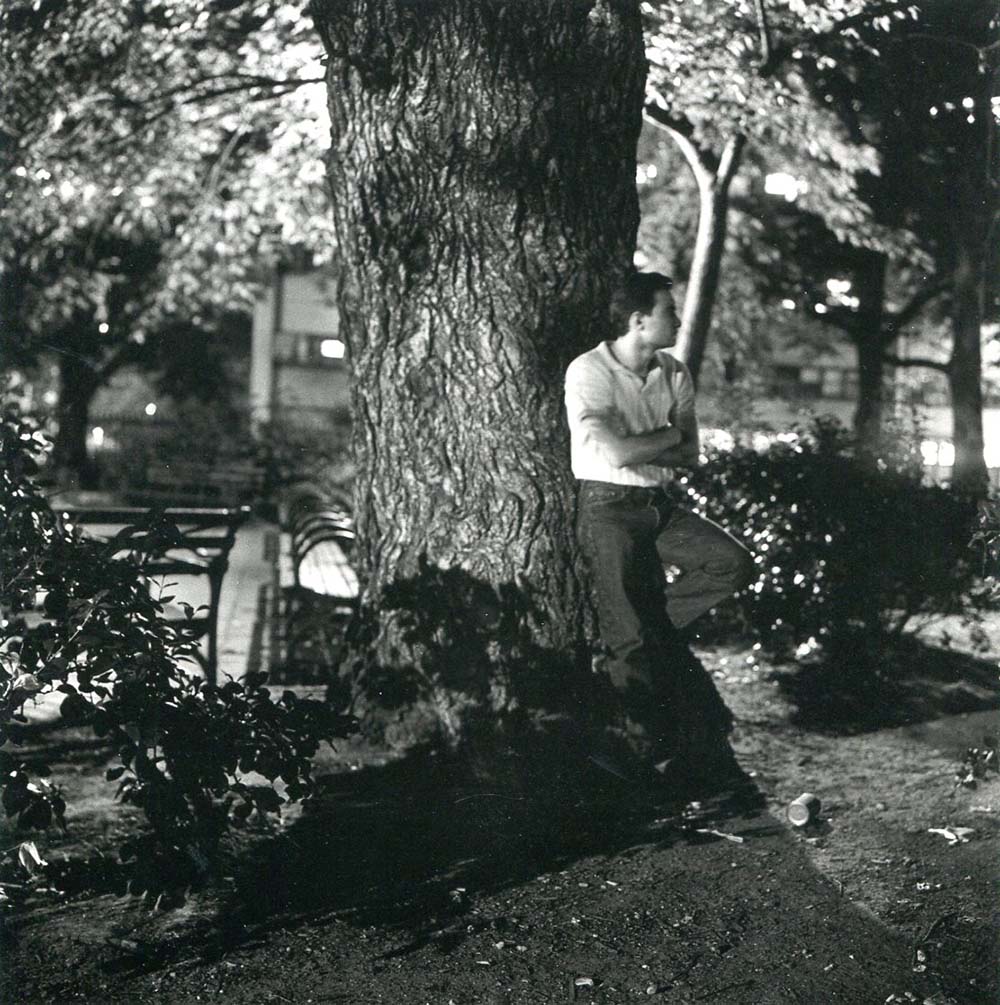

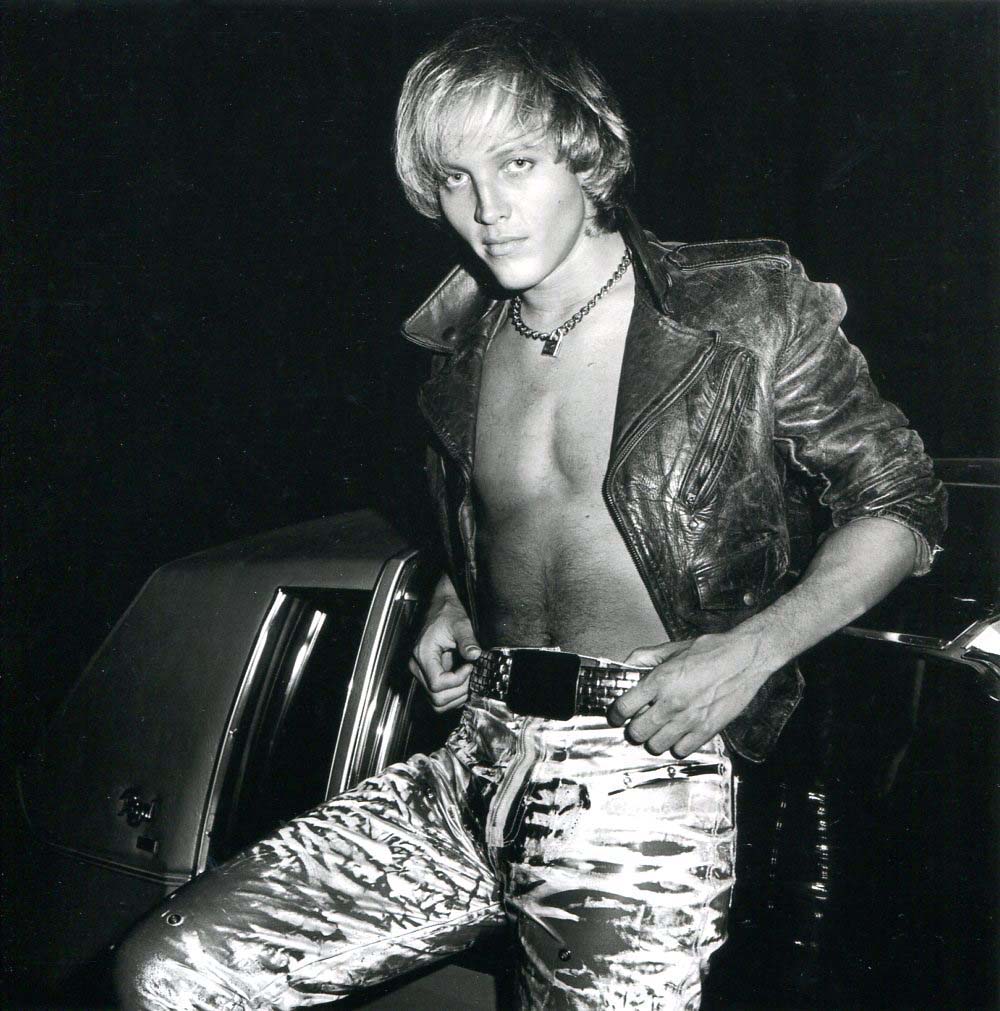

Hujar’s restlessness led him to wander beyond the confines of the studio. Like Brassai, Hujar was a poet of the urban nocturne, prowling the streets with his camera as the day unraveled. Brassai’s Paris is gritty, erotic, sentimental, yet impersonal. Hujar’s photographs of New York’s streets at night embrace emptiness and furtive gestures, glowing skyscrapers, assorted rubble, discarded rugs, boys in drag, and girls passed out in his doorway. His nighttime images of the Hudson river are disquieting, suggesting powerful currents not fully understood by the dappled surfaces. The thrill and danger of an anonymous sexual encounter is manifested in the 1981 image, Man Leaning Against Tree. It is the moment for Hujar to surveille and assess, when the object of desire is seen but has not yet turned his head to return the gaze. There is a little bit of softness in the image, due, perhaps, to the dim light or the camera moving while the shutter remained open. This image is as much a document of Hujar’s habits of looking as it is about the man leaning against the tree. Despite claims of photography’s objectivity or passive observation, the photographer, consciously or not, visually manifests subjective desire, and Hujar was masterful in this regard.

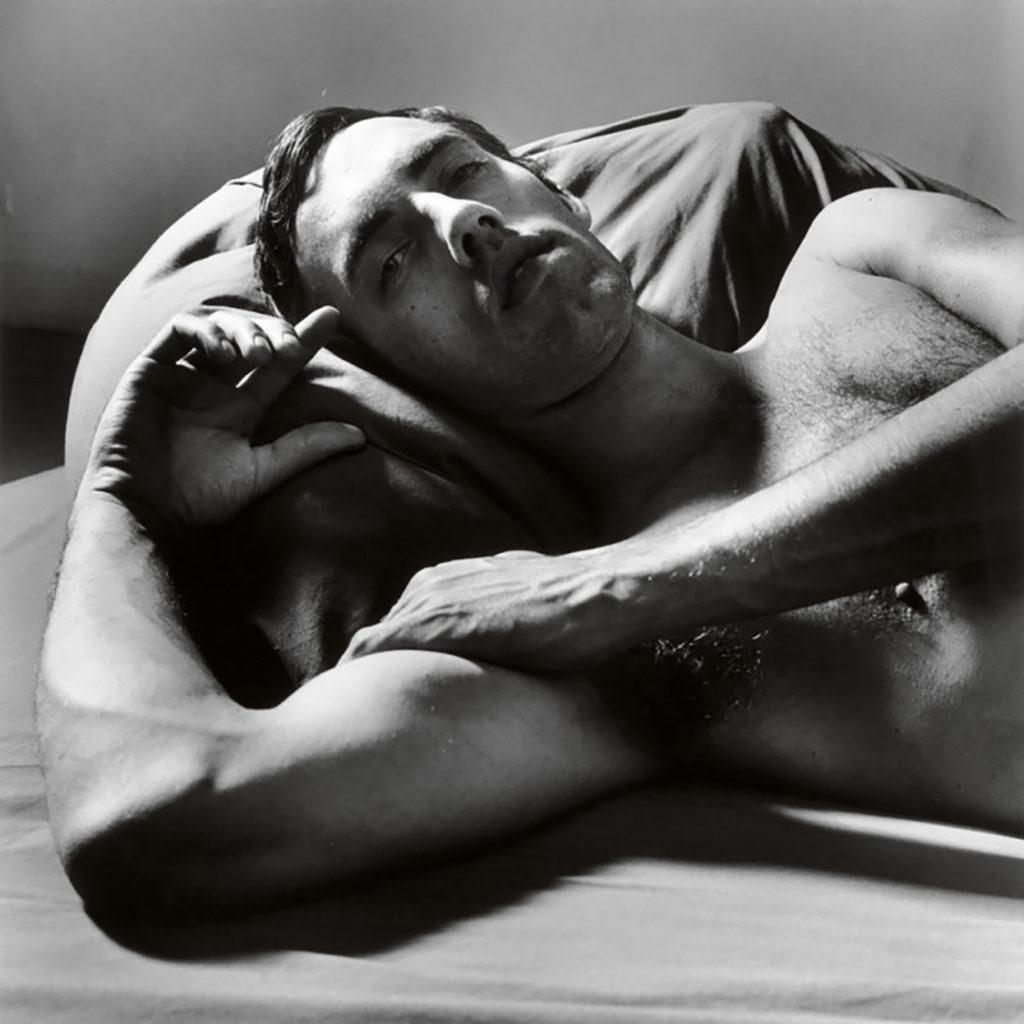

Two of Hujar’s favorite subjects were the artist David Wojnarowicz and the actor Ethyl Eichelberger. Hujar met Wojnarowicz in 1981; they were lovers briefly but their relationship evolved into an intense artistic friendship in which Hujar served as mentor to the younger Wojnarowicz, encouraging him to expand his artmaking beyond graffiti. Hujar’s images of Wojnarowicz are varied in place and mood, from the tough guy persona evoked as his leather-clad friend lights a cigarette on a darkened street to the image of Wojnarowicz reclining in bed, his heavy-lidded eyes softened by affection as he stares back at the camera. Eichelberger was a magnetic presence in the downtown experimental theater scene. Hujar adored his long and angular body, admired his fearless performances, and he became a recurring character in Hujar’s pantheon of subjects. In 1981 alone, Hujar photographed Eichelberger on multiple occasions collectively describing various persona, from an unadorned and somber close-up portrait to Eichelberger as Minnie the Maid perched on the edge of a chair in a long blond wig, bare shoulders, glittering smile, fishnet-clad legs and enormous spike heels.

Hujar died of AIDS-related illness on Thanksgiving Day, 1987. The plague years took so many among his devastated generation, friends and rivals alike. While there is little consolation to be found in those losses, one can be grateful for the images that remain. While all photographs are tethered to mortality, there is something exemplary in Hujar’s cool acceptance of our temporality. He was fully engaged with his moment yet unsentimental in his attachment. Whether he was photographing a lover or an abandoned dog as elegant as it is scruffy, we can sense that Hujar’s interest was intellectual and physical in equal measure. He may not have been comfortable with the world as it was, but he embraced and even loved what was in front of his camera. “My work comes out of my life, the people I photograph are not freaks or curiosities to me,” he said. “I like people who dare.”

This essay originally appeared in Photograph, January / February 2018. Thanks to editor Jean Dykstra.