Odette England

Odette England makes lists of the things she intends to do to photographs, including burning, scratching, burying, microwaving, and immersing in foul liquids. It’s usually something “terribly mean,” she says, laughing, “but it’s always done with a loving hand.” A paradox of contemporary photography is that while it grows ever more ubiquitous, it has simultaneously become less physical. The material presence of photography is increasingly rare. Even the tools we use to make photographs are less and less camera-like. The paper photograph, especially in snapshot form, is an endangered species. England is intrigued both by the “thing-ness” of the snapshot, its presence in the real world, and its connection to personal and collective memory.

England exhibited three bodies of work at Klompching Gallery in Brooklyn in the spring of 2019: The Outskirts, Exposed, and Punched. Each project interacts with photography’s material history in distinct ways. For The Outskirts, England uses, as she often does, her parent’s family album. She scans and enlarges select images and partially covers them with the pages from the photo album from which they were taken. The pages act like curtains – they reveal, veil, block, even shroud significant details. The fundamental theatricality of photography becomes immediately apparent – each photograph is a kind proscenium stage. But by obscuring the subject of the original photograph, the main event, so to speak, England explores what happens when the edges, the periphery, the ambient aspects of the images become the subject.

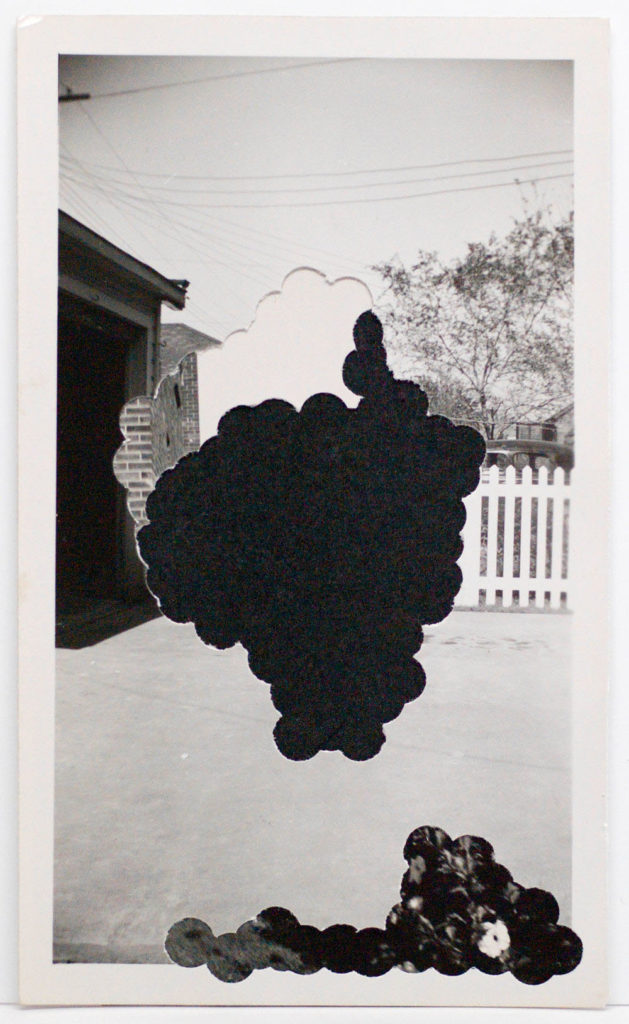

Odette England, Punched #4, vintage photographs, hand punched and layered, 2018, courtesy of Klompching Gallery

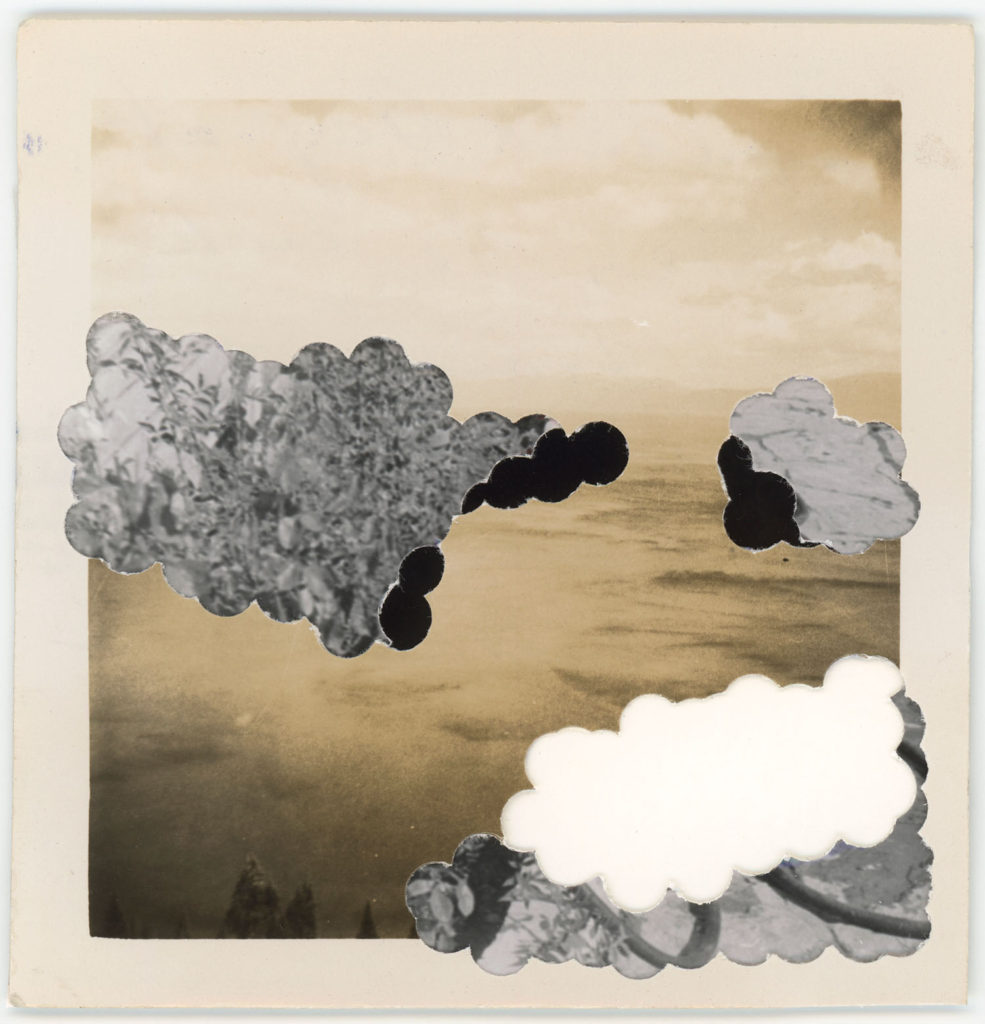

Odette England, Punched #42, vintage photographs hand punched and layered, 2018, courtesy of Klompching Gallery

England thinks of photographs as imperfect containers. She describes them as “leaky” — they promise specificity but often raise unexpected questions. For her most recent project, Punched, she literally makes bubble-like shapes in the image with a hole punch. Again, using family snapshots, she enthusiastically violates the seamlessness of the photograph. She then layers these “injured” images to erase the original content and reveal new possibilities. In a sense, these interactions with photography’s materiality are performative – she tests the images to see what they are. How far can she push an image and have it still retain essential aspects of itself? While she may remove any trace of human presence, the clustered shapes point to her own interactions which are unexpected, playful, and violent all at once.

Originally trained as a painter, England seeks to reassert photography’s physicality. For many photographers, the print is the culminating object; for England, the print is the beginning. She calls herself a “material thinker:” she does things to photographs that cannot be undone, achieving her images intuitively, through experimentation. In finding new ways to interfere with photography’s transparency, England reveals not only photography’s limitations but its hidden possibilities.

Odette England, Margin, Pigment print and vintage and vintage photo album page, 2018, courtesy of Klompching Gallery