Miroslav Tichy

In a Stuttgart bookstore in early 2008, I came across a small catalog of the work of Miroslav Tichy; I was charmed. I was not previously aware of his work and it tweaked my interest in outsider art. I approched the editors of a now-defunct art magazine in New York that seemed interested in obscure figures working on paper so it seemed a natural fit. After some back and forth with the editor he finally stated that although he was both intrigued and repulsed by Tichy’s work, the magazine was reluctant to support it because of his approach to female subjects. For a minute I had to question myself, was I blind or lacking critical sensitivity to Tichy’s misogyny? Was I giving the work a critical pass because of the romantic lure of his biography? Is there something repulsive about Tichy’s work?

What is resisted and what is defended tells us a lot about the boundaries of personal and cultural territory. Consciously or by happenstance artists poke around the edges of things and by extension the viewer is invited to contemplate those limits. There are photographers for whom the response to their work is sometimes more revealing that the imagery they produce. A couple of decades ago Jock Sturges, Joel Peter Witkin, Andres Serrano and Robert Mapplethorpe pushed some cultural buttons exhorting viewers to line up in fervent condemnation or in rabid defense. I was not inclined toward either side of those arguments – for it seems to that trying to balance art and ethics is an unrewarding endeavor. Serrano and Mapplethorpe are more complex artists than those fundamentalist arguments portrayed and while one might be initially taken with Sturges’ budding beauties or Witkin’s metaphysical darkness, the ‘vision’ of these photographers soon becomes tiresome, mostly because the work was/is so predictable: after all, other people’s obsessions are generally a bore. But sometimes, as the cliché suggests, boredom can lead to something else, maybe a relaxed fascination. This was the case for me with Miroslav Tichy’s photographs.

Although he has been a practicing artist for over sixty years, Tichy was unknown outside a small circle of neighbors, friends and supporters, until his scratchy, unkempt, obsessive, lovely yet slightly creepy imagery was unveiled to the art world at the 2004 Seville Biennial. Since that introduction there has been a rapidly growing interest in his work and biography including several monographs, a documentary film, website, and a flurry of major exhibitions including the Pompidou Center, the Syndey Biennial and the Museum of Modern Art in Frankfurt. That Tichy does not travel to his exhibitions and appears to be entirely uninterested in the fate and reception of his photographs only increased the charm. Tichy is being packaged as a modern primitive. It’s the art world’s version of finding a stone-age tribe in the Philippine rain forest. He is ragged, dirty, primitive but pure, toothless yet sweet. I do not suggest this is malicious or even inappropriate. It is difficult not to mythologize his character and since he does not possess the university-trained self-consciousness of a contemporary artist to contextualize himself, I suppose this was inevitable.

A delicate child of a tailor, Tichy was born in 1926 in a small village in Moravia. In 1945 during a brief interval between war and dictatorship Czech culture attempted to shake off the darkness. Fueled by provincial enthusiasm, Tichy adventured to Prague to enroll in the Academy of Fine Arts to study painting. But the clampdown returned in 1948 when the Stalinist government fired faculty and replaced the nudes of figure drawing class with heroic proletarians brandishing hammers. The suppression of creativity seems to have coincided with the onset of psychological troubles that have plagued him for decades. For personal and political reasons Tichy retreated to his childhood home where he has lived since, becoming, in essence, the village madman, both avoided and occasionally loved for his stubborn eccentricities. With his wild long hair and beard, obvious scorn for personal hygiene and rejection of ennobling labor, Tichy’s personal decay represented a daily mockery of the ideal socialist man. Over the years Tichy was regularly assaulted and arrested by local officials and often committed to institutions against his will.

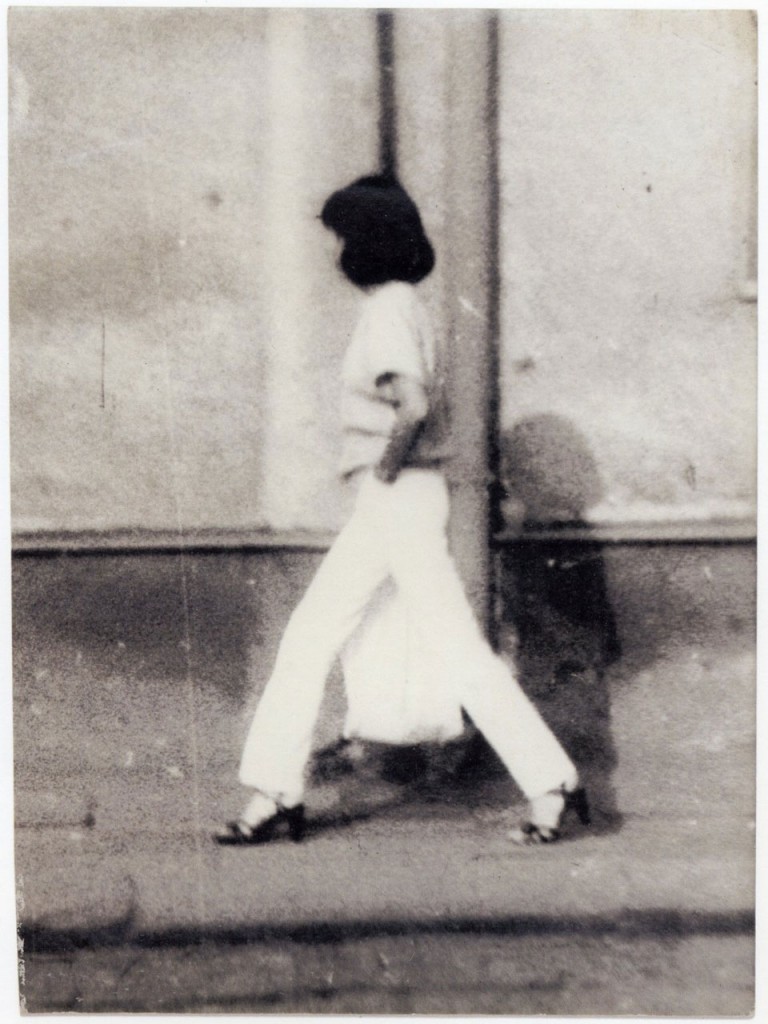

Sometime in the 1960s Tichy stopped painting and adopted a primitive form of photography by cobbling together cameras from bits of discarded Russian models customized with toilet paper tubes, wooden spoons, string and plexiglass lenses. For the next quarter century, with his fake-looking camera poking from beneath threadbare coats and sweaters, Tichy shot 100 frames a day, mostly of female citizens of his village. The process by which he printed his imagery was equally disrespectful of photography’s clean and precise habits; he developed his film in a tub in his courtyard at night, hung the film on a line as if to dry his laundry. The enlarger looking as if it had been recently unearthed produces blurry and vignetted effects and his fingerprints are a regular feature on the surface of his images. He will only make a single print from a negative, he mounts the photograph on construction paper or cardboard and often doodles a decorative pattern around the image. Hundreds of such images have spent decades in random piles around his chaotic environment gathering dust, scratches, mouse nibblings and assorted stains that collectively serve to burnish the aura of his imagery and legend.

Previous texts on Tichy have made reference to Polke, Richter and the Starn Twins and in terms of surface and affect these comparison are apt to a point. If the conventional photograph is supposed to be a transparent envelope, to use Barthes’ term, then to interfere with its clarity is to obstruct its immediacy – to point toward other subjects beyond the thin pictured. The self-conscious manipulation of photographic surfaces and processes by Polke and the Starns lead us to think about history and the spectacle of its representation. Is this what Tichy is up to? The aggressive street photographs of women made by Garry Winogrand or even the unintentional decay of Bellocq’s New Orleans’ prostitutes might provide some interesting historical tangents. And with all of the dust and detritus that immerses his work and life, Tichy could be an escapee from the set of a Brothers Quay film, he is even the son of a tailor! But will these varied contexts help in understanding Tichy’s obsessions?

Watching the documentary Tarzan Retired, it is evident how Tichy’s environment is transformed by his closed-circuit fantasy life; this colorful, 21st century town, complete with street traffic, internet cafes and kids in hip hop fashion is all but invisible in his monochromatic, diaphanous, furtive, vaguely erotic imagery. At first glance his pictures may appear voyeuristic and predatory but they lack the malice or ulterior motive of someone truly creepy. Cumulatively they are all the same – endless variations on the fairly chaste longings of a man who has lived without intimacy. Are these repulsive pictures? Only if you lack imagination and cannot summon an ounce of feeling for an old man who wanders the streets attempting to embrace, photographically at least, that which because of politics, mental instability or the simple fact that growing old, is, and perhaps has always been, beyond his grasp.

Originally Published in Pluk Magazine, Fall 2008