McDermott and McGough

THE INDEPENDENT ORDER OF ODD FELLOWS

In 1990, somewhere between Green Bay and Milwaukee, Wisconsin, I discovered time machine. Coincidentally I happened to be returning from an academic conference where I participated in a panel titled “History as Source.” On the way home to Chicago, I stopped at a number of diminutive and dusty secondhand stores whose contents were bravely considered antique by the shopkeepers. As an artist, I am naturally interested in discovering objects with a certain aura. Despite Walter Benjamin’s early twentieth-century warnings about the reactionary and decadent value of aura in the age of mechanical reproduction, one might observe that artists are solely interested in collecting and cultivating aura. With my auratic detectors in full alert, as if vintage Geiger counters, I scanned the shelves and glass cases for kitschy authenticity. When my eyes passed over a barnyard animal cookie jar or a heavily airbrushed photographic portrait of a farm family, my acquisitive glands pumped “I’ve-got-to-have-this” juice into my internal stream. My eyes widened, not immediately in recognition, but rather in covetous delight when they rested upon an enigmatic object bearing the poetry “McIntosh Stereo-0pticon Co. Chicago” stamped in the metal housing.

The lens barrel as well as the focus knob was of polished brass, the bellows brown leather, and the lamp housing a dark gray with a delicate red-flowered vine motif painted around the edges. The lamp’s height could be adjusted with a wooden knob; the bulb- with all manner of grotesquely twisting filament- looked like something from Dr. Frankenstein ‘s laboratory. Humbly sitting beside my nineteenth-century beauty, and blinded by my lust for archaic projection machines, I did not initially see the real treasure chest, a slotted wooden box full of glass slides. Nineteen 3″ x 4″ black-and-white and hand-colored images were resting in seemingly random order. Several of the slots were empty; already I mourned their absence. Dislodging a glass slide and holding it up to the fluorescent lights above, I brushed aside a grimy coating of dust with my thumb and revealed a slash of primaries, sky blue and cherry red. I pulled a white cotton handkerchief from my jacket’s inner pocket and wiped the crystal to uncover the remainder of the image. The specimen showed a gathering of Cigar-like stubby branches sashed together by a red ribbon, floating on a tricolor background of brown, pink, and blue. The label on the slide read, “6 – Bundle of Sticks”, and like a jack-in-the-box, the tune of ‘ This Old Man” popped into my mind, “with a knickknack paddy-wack, give a dog a bone …. ”

Inspection of the entire group of image-objects revealed a most eclectic portfolio, with representations and juxtapositions of the strangest order. Biblical references mixed with allegorical images, universally recognized symbols, and obscure icons rested side by side; a hand-painted hourglass was followed by a skull and cross bones, a Bible floated above a blue ground. Three links in a chain, an axe, a scythe, scales and sword, and a bow and arrow were etched into the surface of t his century-old glass. Images of tiny figures inhabited dramatic landscapes with labels reading “Narrow Defile” and “Pines on the Mountainside.”

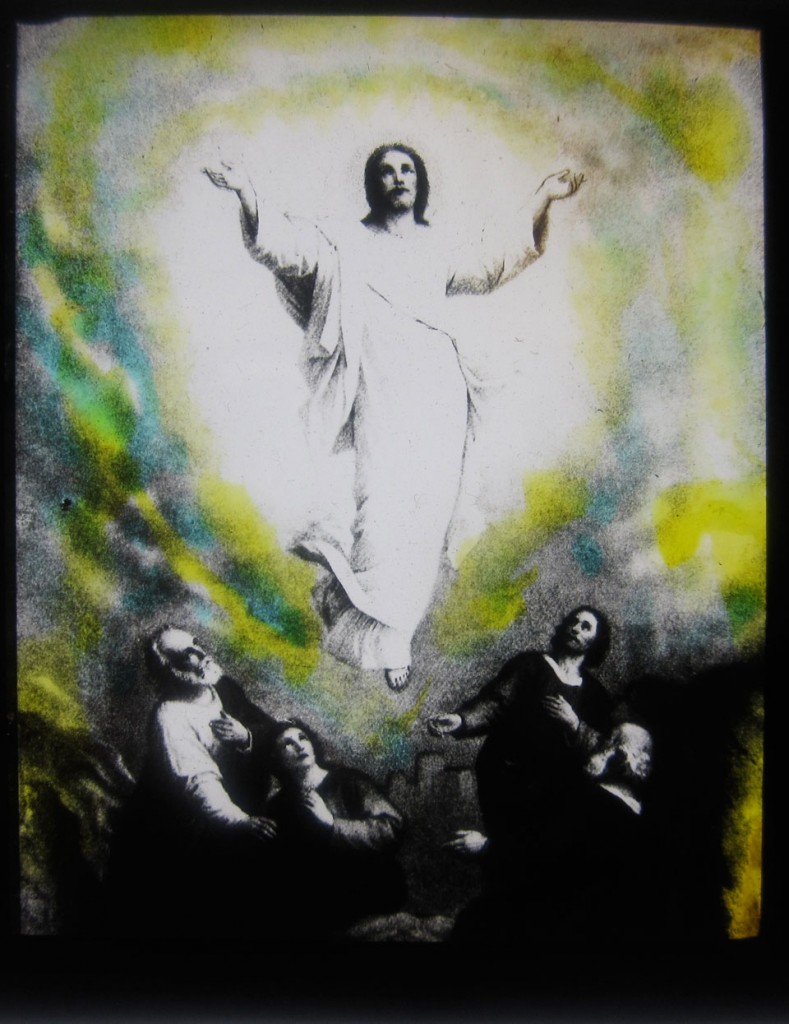

Strangest of all, and seemingly out of place, were photographic slides of what I presumed to be colonial missionary activity in what appeared to be Africa. A white man in safari attire topped by a pith helmet stands triumphantly with hands on hips a few feet away from a gesturally more uncertain black man who holds his hands in front of himself looking vaguely worried. Another image shows five black men digging a large hole that could be a building’s foundation or a mass grave. In the background another helmeted Caucasian blurrly steps into a wooden structure. A third image simply presents a bare-footed peasant-acolyte in loose-fitting robes standing in front of a stone wall holding a dark volume. He seems to smile slightly as if inspired by the words within. This pictorial extended family was topped off by the final slide I removed from its slot, a hand-painted image of the Ascension of Jesus into heaven. With upraised hands, eyes turned above, Jesus floats in a swirl of blue and yellow ectoplasm, while Mary, Joseph, and assorted apostles cower below.

Familiar and foreign, these images floated freely from their original contexts; without narrative they were both specific and mysterious. What meaning, if any, was there in this found collection? Was there a relationship between the three links in a chain to the rod and serpent, between the photographic ghost of a holy man and the kitschy representation of an hourglass? Dislodged from a language to make these loaded symbols and fugitive figures meaningful, I was free to construct my own narrative and I found myself daydreaming a fantasy world of priests and initiates who knew enslavement and redemption. I imagined a secret brotherhood with its own passwords, handshakes, bizarre rituals, and oaths to secrecy. Grown men playing little boys’ games, yet the playing field, the backyard, so to speak, of these games was the very real world of colonial relations.

There was one clue yet to be deciphered: initials teasingly scripted on the label of one of the slides, The hand-painted image depicted two robed figures standing at the edge of a roiling sea, a silvery orb floating over the horizon. Under twin palms, the figures stand with their backs to the viewer. They wear large golden hats and carry long staffs, and one beckons to the top of the cliff. The label reads “I.O.O.F. Second Degree – Pines on the Mountainside.” I later discovered that these initials stood for The Independent Order of Odd Fellows, a nineteenth-century fraternal organization that in 1896 boasted 810,000 members in the United States. Among the many fraternal organizations that flourished in Victorian America were Freemasons, Knights of Pythias, Improved Order of Red Men, Knights of the Maccabees, and Modern Woodmen of America. Along with the Odd Fellows, these organizations claimed the membership of more than forty percent of the adult male population in the United States at the turn of the century. These societies had multiple functions, not the least of which was replacing rural, agrarian, familial, and religious social orders that were being undermined by rapid industrialization and urbanization.

The majority of the glass slides residing in my slotted wooden box were projected during Odd Fellow initiation rites. The membership utilized such symbols as the bundle of sticks, the ark, and the scythe to anchor ritual narrative, to heroicize homo-social behavior, as well as to provide historical (albeit invented) continuity. By mining the past for meaningful icons, an entire constellation of myths and legends was cobbled together in new configurations. Add a little sense of irony to process and it sounds a lot like the dominant art strategy of 1980s post-modernism. Why the colonial photographs and the Ascension of Jesus image where among the fraternal order’s pastiche of historical symbols remains mysterious. Yet as coincidental as juxtaposition may have been, there may be an underlying relation between these seemingly disparate types of images.

The Ascension of Jesus is the reigning symbol in the Christian West of the triumph over the temporal, a victory of the spirit over the doomed flesh, a resurrection of life in the face of death. The conflation of martyrdom, redemption, and eternal life in Christianity most certainly provided the powerful element of the messianic in the colonial impulse. Phenomenologically speaking, the photographic slides of missionary activity seem to be of a different order. They are, like all photographs, rooted in the specificity of time and place. Even if the contextual information is lost, there remains the undeniable fact that these men, wrapped in tattered cloth, stood in the soft and wet soil of the shallow foundation, shovels strewn about, squinting in the direction of the photographer. And it is certain that they no longer live on this earth. Photographs are chained to the temporal and with that fact comes the melancholy of their existence. The odd assortment of icons, such as the scales or the bundle of sticks, and even the Ascension of Jesus operates solely in the realm of the symbolic, and although a photograph may function symbolically, it contains an existential power that no two-dimensional sign can ever attain. This is what differentiates photographs from all other forms of representation; the photograph is a trace, an emanation, a ghost of a specific time, person, and place.

The Odd Fellows were not alone in their impulse to create alternative social structures. The founding myths of colonial America are idealist and escapist; from the Pilgrims to the Mormons, social and religious utopian movements blazed the paths of American expansion from a few beleaguered communities to a continental power. The Inspirationists of Iowa, the Harmony Society of Pennsylvania, the Society of Separatists and the Grahamites of Ohio, the Perfectionists of upstate New York, and the Aurora Communes of Oregon are but some of the many communitarian and utopic societies that offered alternative religious, political, dietary, and philosophical models for social organization. Some of these societies were disdainful and even openly hostile to the dominant American identity that was characterized by secularization, immigration, and increasingly antagonistic labor and capital relations.

Americans have been characterized as a forward-looking people, sometimes to a fault. Consider the apocryphal tale of the Chinese Ambassador who commented, “Americans are so charming, they have no memory.” Idealism and forgetfulness seem to be the secret ingredients for assimilation, success, and progress. As American artists, McDermott and McGough intimately know and explicitly challenge that most fundamental of American myths, that of progress. McDermott and McGough parade themselves in the present like lost ancestors whose very presence questions the hermetic seamlessness of our present moment. While their aesthetic strategies are representative of the late-twentieth century, their philosophic sensibilities feature the nineteenth-century qualities of eccentric individualism, fraternal Iove, and utopic idealism.

“I HAVE LOOKED INTO THE FUTURE AND I HAVE NO INTENTION OF GOlNG THERE.” -David McDermott

Considering the slippery notions of time espoused by the collaborative duo of David McDermott and Peter McGough, one wonders about the relevance of such things as fixed dates of birth and other biographical details. But since context determines meaning, the cumulative details of a life lived, even if it is a “performed” life, can lay the foundation for a necessary, if unstable, structure of facts. McDermott was born in Hollywood, California, in 1952, although he spent the majority of his childhood in New Jersey. McGough was born in 1958 in Syracuse, New York, where he lived until moving to New York City to attend the Fashion Institute of Technology in 1977. Coincidentally, David attended Syracuse University studying Advertising Design in the seventies but their paths never crossed until they were both living in New York City a few years later.

McDermott claims to have always been attracted to “old-fashioned things.” As a fourteen year-old he tried on a pair of high top lace-up shoes from the turn of the century, and, as if slipping on Dorothy’s ruby slippers everything changed, including his relationship to walking and running and, of course, his relationship to everyone else around him whose feet bore sneakers and penny loafers. This memory evokes the same talismanic quality that objects can have for the imagination, especially clothing with its direct relationship to the body and to the timeliness of fashion. Donning a frock coat, a top hat, a corset, and other such magical items, the body is pushed, pulled, tucked, adorned, exaggerated; such donnings transport the individual to another time, another worldview, and an altogether different aesthetic via the body’s relation to itself and to social space.

When David and Peter met in New York City in the early 1980s, the art world was exploding: the number of artists, art spaces, art magazines, and artworks being sold was growing exponentially. Art careers rivaled Hollywood glitz, Wall Street stockbrokers were jealous of the killing some painters were making in the art market” It was a unique moment in art history, a charmed and corrupting decade to be an artist in New York” Resuscitated from its conceptual beginnings, performance art returned metamorphosed in a big way with the spectacles of Laurie Anderson and Robert Wilson on one end of the performance spectrum and the transgressive monologues of Karen Finley and Spaulding Gray on the other. The “act” of being an artist became performative. Artists “played” at being artists; Jeff Koons, Mark Kostabi, and Jean-Michel Basquiat were but a few of the children of Warhol playing in the ruins of taste, high on celebrity, kitsch, and self-as-commodity” How artists presented themselves was as much a part of the art as the art object itself.

Obvious predecessors to McDermott and McGough are the British artists Gilbert and George who began collaborating as art students in the late 1960s. And like McDermott and McGough, Gilbert and George came to photography via other media. Coming of age as artists when the primacy and relevance of the art object was in question under the assaults of minimalism and conceptual art, Gilbert and George initially employed their own bodies as sculptural objects. The “performative” life they invented for themselves functioned not only as a way of exploring the body as active sculpture but as a way of investigating the interrelatedness of maleness, sexuality, British-ness, and class could be illuminated via simple, socially motivated actions. Choosing the relatively unpretentious medium of photography, Gilbert and George began creating spare, minimal, and monochromatic photographic sequences and grids as a way of both documenting the conceptual and exploring the pictorial. As their careers progressed they added bright primary colors and built their photographic sculptures in grand scale, as the content explored more explicitly homo-eroticism, desire, repression, morbidity, and AIDS. Their humble photographic works of the early 1970s blossomed into the “big picture” movement of the 1980s.

It is in this milieu that McDermott and McGough found each other, becoming aesthetic and spiritual collaborators. Recognizing in common, a yearning for a cultivated elegance not found in the present era, they began to think that it might be possible to create a world within a world. This was not to be just some fancy version of escaping the proverbial rat race but more of a proposal of time experimentation, an attempt to live in at least two worlds simultaneously, creating a skip in the progressive linearity of history. To this end, they moved into a duplex on Manhattan’s Lower East Side and ripped out the electricity, light fixtures, copper plumbing, shag carpets, and other artifacts of twentieth-century modernity. Utilizing wash basins, bed pans, ice boxes, and kerosene lamps in their daily activities whilst wearing Edwardian waistcoats and plus fours- and reading only literature from the nineteenth century-McDermott and McGough created within their own walls a totally encompassing environment. More than antique collecting run amok, this transformation was not in service of a feverish nostalgia but represented attempt to transform a late-twentieth century consciousness to one from the late-nineteenth century through total immersion in the cultural artifacts of that period. Like characters from a lost Jules Verne manuscript, McDermott and McGough are both the mad inventors and the subject/specimens of their extraordinary machinations of time travel.

This bubble of dandyism could have a stupefying effect upon ordinary citizens of the late-twentieth century. Imagine yourself going about your daily errands, a plastic sack of tomatoes in one hand, your cell phone in the other, speaking loudly into the mouthpiece so that your English friend may hear your Brooklyn accent over the street sounds of the Lower East Side. You stop for a moment on the corner to listen intently to the voice from London whispering into your ear. You think to yourself, “This technology is amazing, miraculous, yet I have no idea how it works.” Across the avenue you spy two young men, one is wearing a top hat and a long-flowing overcoat, the other, on his left, is wearing a fedora with its brim turned up. The taller man on the right is clasping his hands behind his vested chest, his gloves perch above his coattails. The man on the left laughs heartily while bending to adjust the buttons on his plus fours. High starched collars enclose both of their necks and seem to prop up their heads in an unusual manner. Even the way they stand, awaiting the change of traffic signals, sets them apart. More erect, seemingly serene, oblivious to the visual, auditory, and cultural cacophony that is the experience of these streets, you cannot even begin to guess whence these ghosts come, and you question where it is exactly you are at this moment. Is the present haunted? Is time stable? Are who you see just a couple of odd fellows?

McDermott and McGough initially achieved notice with paintings that explored themes as diverse as homoeroticism, nineteenth-century men’s fashion, and vegetarianism. Their time traveling was made implicit in their canvases through time-specific subject matter and formal elements, but most explicitly in the strategy of backdating the paintings to the year that seemed most appropriate. In the 1987 Whitney Biennial their painting A Friend of Dorothy, 1943 caused quite a stir. Inspired by a Stuart Davis painting from the early 1920s in which phrases such as “banana royale” and “hot fudge sundae” hover and inter twine in a linguistic play of pop poetry, McDermott and McGough substituted a litany of homophobic epithets. Denigrating words for homosexuals in the I940s such as “faggot,” “queer,” “fairy,” and “cocksucker” create a free-floating field of slurs and accusations. In a visual and rhetorical gesture of acknowledgement and owner ship, the painting subverts the power of insult and marginality. In a sly manner it also historicizes the secretive demimonde of gay euphemism in its reference to Judy Garland in The Wizard of Oz by implicitly declaring that we are not in Kansas anymore.

A dominant visual strategy of 1980s post-modernism was appropriation of preexisting imagery through quotation and recontextualization. Collage, montage, pastiche, and layering were prevailing techniques utilized to create an allegorical relationship to history and historical motifs. The use of allegory is inherently discursive, it is a dialogue between the present moment and what has come before, it is a strategy that puts into question the meaning of symbols and texts in relation to the iconography of history. The 1980s was a decade in which our culture turned its sights toward the past in an attempt to review, reassess, and revise the images and narratives that had come to define us. Be it in rhetorical or mythical guises, artists as disparate as Barbara Kruger, Anselm Kiefer, Jimmie Durham, McDermott and McGough, and many others, were in their own ways, mining cultural memory as a way of exploring how the unresolved contradictions and omissions of history have shaped our present condition.

McDermott and McGough’s project is multi-faceted, not content to simply mine the past, they actually want to go there, not by leaving the present but by creating a parallel universe, a simultaneity of time, a hermetically sealed world within our own, impervious to the contagion of late-twentieth-century modernity. Just as the look of their images is historicized so it is that their history is imagistic. Their work is painterly, photographic, and performative, yet these three modes are not mutually exclusive but inextricably bound to one another. The “performance” of the work revolves around the notion of extreme historical subjectivity; whether it is in their paintings, their photographs, their domestic life, or public persona, McDermott and McGough are revising the historical visual record. At times their motifs seem quaint, nostalgic, and perhaps even reactionary. Yet their yearning is not for the perfection of the past-they implicitly acknowledge its imperfection-but rather they would like to manufacture a history that never was, a history of tolerance and gentility. All aspects of their art are time experiments that propose that if one could return to begin again, insert oneself into the narrative, occupy the absence, reassert the erasure, then in some good and fundamental way, life in the present moment would be more humane.

As old-fashioned as they may seem, the paintings (and photographs) speak of another modernity, one that now seems quaint, anachronistic, but at one time was progressive and threatening to an older order. Three paintings from the early 1990s illustrate McDermott and McGough’s unique blend of homoeroticism and turn-of-the-century progressivism. The symbolic and compositional elements of Soul Mates 1918/1991 are based upon an advertising design for a new-fangled invention of the time, the electric light bulb. A moment of homosexual passion is caught, framed in the filaments of modernity, as if this love could light up the darkness of previous centuries. This bulb is like a Victorian glass dome, enclosing in the invisible vacuum a passion transformed into a frozen shrine. This icon of modern illumination is a perfect phallic vessel of desire, an announcement of a most extraordinary embrace (which reminds me of Act-Up’s “read my lips” campaign), a terrarium of forbidden love and light.

Chart 5 1904/1990 references anatomical, physiognomic, and phrenological charts that categorized human traits and behaviors according to various criteria. The inventions of the time-keeping devices, electricity, telephones, gramophones, automobiles, and cinema, as well as the manias and pseudo-sciences such as séances, eugenics, and phrenology, promised a new world, a world fundamentally different from previous epochs, a time in which science, technology, and spiritualism would help society shed its inequalities and soothe life’s cruelties. Chart 5 1904/1990 gently mocks the obsessive compartmentalizing of the human brain, as if the mysteries of desire could be named and pinned to cushions like butterfly specimens. Areas of the brain are circumscribed with historical dates, but this system is obscured by the names of men, Lance, Ed, Theo, and so on, as if to say that personal, anecdotal, and perhaps, even erotic memory supersedes the merely chronological. Captioned with the text “He loved boys, artists, and aristocrats,” McDermott and McGough transform what could have been a proof of perversion into an unmistakably proud declaration.

Finally, Echo Homo 1919/1992 presents a hybrid of fashion advertising and messianic revisionism. The snazzy heads of six men float against a dramatic sky of billowing cumulus clouds as the crucified Christ occupies the compositional and symbolic apex. In their original context, the men were most likely portrayed as chaste dandies sporting the latest trend in haberdashery, men of the world who were up-to-date but fundamentally harmless. In McDermott and McGough’s universe, their previously neutral smiles become knowing glances of recognition and sexuality, creating a self-enclosed economy of shared sensuality. Christ centralizes the composition and Pontius Pilate’s words “Ecce Homo” are tweaked to anchor the piece in a somewhat blasphemous manner, showing that McDermott and McGough are not content to revise secular historical figures but would like to address the eroticism and homo-sociality of the figure of Christ as well.

THE SPIRIT OF PHOTOGRAPHY: FIXING GHOSTS

Although successful experiments had been performed decades earlier, the generally accepted date of photography’s invention is 1839; the year Louis Daguerre announced his process of fixing an image on a polished copper plate. Nicephore Niepce, Daguerre ‘s hapless partner, lived long enough to share his photographic experiments with Daguerre but died before reaping any acclaim or money. Across the English Channel, simultaneous and unbeknownst to Daguerre, Henry Fox Talbot was having spotty success with his paper -negative process, creating haunting photograms of lace patterns and ghostly silhouettes of blossoming flora. The birth of what was to become the most ubiquitous and influential of mediums was not the invention of the camera. The camera obscura and similar optical devices had been in use for centuries by artists, anatomists, and scientists in aiding the rendering of nature onto a two-dimensional surface. The treasure box of our image-glutted contemporary society was the fixing, or capturing, of the image in a stable and reproducible manner.

Roland Barthes has noted that the century that invented history also invented photography. Critic John Tagg reinforced this notion when stating “History and photography, the two steam-engines of representation, are given to us as inventions, devices, machines of meaning, built in the same epoch under the sign of the real.”’ For most of us, history looks like an image/text combination; the image embodies the text, illustrates its point, and gives evidentiary force to its truth while the text elaborates on the visual clues of the image and anchors its ambiguity. This semiotic marriage of photography and language has, since its inception, been a seductive device for persuasion, condemnation, and both validation and invalidation. When this marriage is dissolved, the photograph floats away like an unmoored balloon. Without narrative, the image shakes loose of its predetermination; it is resuscitated, alive with possibilities. Again, this serves to illustrate the point of a photograph’s essential ambiguity; the photographic image carries an undeniable indexicality, a mark left by past events, but as it is also fragmentary and elusive, it needs language to give it context. The photograph standing alone remains an enigmatic image / object.

As film historian Tom Gunning has noted “In the nineteenth century we enter new realm of visuality, and it is the photograph that stands as emblem to this new world.” Although incubated in the nursery of science during the early years of the medium, the essence of the photograph remained mysterious. Photography historian Geoffrey Batchen has investigated the notion of “uncertainty” that clouds the medium’s birth. The language employed by its inventors, Niepce, Daguerre, and Talbot to describe the process of acquiring the image was strangely passive. They understood the optical, chemical process, but on a phenomenological level it occupied the realm of the uncanny. Daguerre described his own process as “the spontaneous reproduction of the image of nature ‘ received’ in the camera obscura.” Talbot thought his process “imitated” his botanical specimens in photograms, even going so far as to believing that the object drew its own picture; photography was “nature’s pencil.”

The earliest photographic images rendered a detailed impression of the subject’s materiality, and, through the process of doubling and repeating, it seemed to destabilize reality by producing a ghost image, a dematerialization of the three-dimensional world ‘” How was the image transferred to the photographic plate? Did the spirit or essence of the subject somehow reach into the camera and impress itself upon the light-sensitive material? Did the image lift off the subject like a skin? Were these immaterial skins constantly being shed or, more maliciously, did the camera somehow strip them off? How many layers or copies could be made from the subject before it became insubstantial itself? Were there a fixed number of layers, and was there a relationship between the number of layers to be shed and the length of one’s life? Did one’s life end when the last skin was shed? You can see how such a litany of questions stimulated by a scientific process quickly led to metaphysical speculation.

Photography in service of science and history proved to be a most utilitarian medium, proving such phenomena as horse’s hooves leaving the ground in full gallop and the horror and violence of battlefield engagements of the Civil War. Paradoxically the specificity of the photograph served the supernatural and the talismanic. Alongside the experimental studies of Edweard Muybridge was the parallel universe of spiritualist movement. Certain Victorian minds associated photography with the occult, believing the human eye did see all, that human perception was blind to the spirit world. Occultists believed the air was charged with floating images and disembodied spirits, and they set out to prove their claims by documenting episodes of “visitations.” Even Alexander Graham Bell’s invention, the telephone, was initially suspected of transmitting the voices of the dead. In a continuum, with science and the occult bracketing opposite poles, photography inhabits the center position.

Queen Victoria, who gave name to the entire epoch under consideration, came to the throne just months before Daguerre’s method was patented in England. During much of her reign a signet ring containing tiny photographic portraits of her family adorned her royal finger. Photographs became ubiquitous; a democratic process of historical representation, they replaced silhouettes and other forms of inexpensive portraiture. The photographic ghost acted as a kind of guardian angel; alchemical traces of loved ones hung on walls, sat atop mantelpieces, hid in treasured secrecy in lockets dangling from powdered necks and nestling between breasts. Whether it is in the hard-mirrored surface of the daguerreotype, in the amber glow of albumen, in the diaphanous platinum/ palladium, or the watery melancholy of the cyanotype, the photograph became a way of privatizing history. As Susan Stewart has noted, “The photograph as souvenir is a logical extension of the pressed flower, the preservation of an instant in time through a reduction of physical dimensions and a corresponding increase supplied by means of narrative.”

Despite photography’s long association with “truth,” from its inception it has been inextricably bound to the theatrical as well. I think it no coincidence that before he devoted his life to photography, Louis Daguerre designed and constructed theatrical dioramas. Monumental screens of gauze would unfold like a player piano roll revealing exquisitely detailed epic narratives, paintings of historical figures, faraway places, and atmospheric conditions. Like Niepce and Talbot, Daguerre yearned to invent a process in which nature in all its mysteries could be captured and history in all its drama could be stilled. The medium was embraced by nineteenth-century Western culture and in that way became a mirror for its manias and obsessions: science, criminology, westward expansion, ethnography, colonialism, the occult, and pornography. Photography is more than a practice, it i a multifarious phenomenon that changed the way we understand time, the manner we visualize the past, and how we occupy the present.

POSTCARDS FROM THE PAST: HAVING A LOVELY TIME, WISH YOU WERE THERE

The history of photography is not simply a progression of technical and formal advancements made by artistic and scientific visionaries. The history of photography is a history of ambiguity. Every photograph is, in itself, a displacement of time. Every photograph is a time capsule sent into the future with a simple message, “this is what things looked like.” Images from the past fill our eyes, and the present is like an enormous iconostasis we must pass through in our attempt to communicate with our ancestors. But what if our ancestors are absent from the visual record? How can we fill in what is missing from personal and collective memory? Can a photograph, which more than any other form of representation is anchored in time, be made in the present to rectify the past? Can a photograph at least suggest a presence that had been missing though blindness, amnesia, or erasure? If so, what kind of performance would be necessary to pull it off? What theatrical gesture could carry the weight of historical revisionism?

“Yet it is not (it seems to me) by Painting that Photography touches art, but by Theater,” so states Roland Barthes in Camera Lucida. To photograph is to theatricalize. To frame a part of the world with an optical recording device, whether it be a street scene captured with 35mm camera or a studio still life rendered with an 8″ x 10 view camera, is to create a proscenium, a theatrical space in which the photographer is the director. Select any photographer from the history of the medium and one could view the relationship of their images to theatricality in terms of time and place. Civil War photographer Matthew Brady was known to shuffle the location of corpses in the aftermath of battles so as to create more effective compositions. Bill Brandt often used family members as actors in his supposedly documentary images of the British class system. What is the location, geographically and temporally speaking, in the contemporary photographs of Joel-Peter Witkin or Cindy Sherman for instance? Both construct an almost mythical past-in-the-present world in which their photographs refer to images from the past, yet clearly their work speaks about the present moment. In the photographic process, the combination of theatricality and the specificity of time creates a paradoxical image/object that contains and represents a moment saved or stolen from the past.

In 1987 a friend suggested that the two painters try their four hands and four eyes at photography. In their foraging of secondhand stores and antique shops, the duo discovered a turn-of-the-century 8″ x 10″ view camera, which their friend and colleague Adam Fuss taught them how to operate. The maiden exposures were made of the interior of their apartment on Avenue C. Using the objects of their home, they set up still-lifes, tableaux vivants, and David modeling while Peter labored beneath the black cloth behind the camera. Various factors contributed to lengthy sitting times, which were an experience of a different order than that of instantaneous exposures of contemporary processes. A seventeen-second exposure is not a click but an embrace; it is not a theft of the soul but an invitation to exist, not a frozen moment but a deep impression.

The initial prints were unsatisfying in the cold contrast of a contemporary gelatin -silver emulsion. This prompted McDermott and McGough to research other photographic materials more suitable for the subject matter. Cyanotyping, based upon the light sensitivity of ferric salts, was commonly used in the mid-nineteenth century to reproduce images of botanical specimens, and the process enjoyed an artistic revival at the turn of the century. Cyanotype emulsion requires long exposures to ultraviolet light; nineteenth-century prints were made by exposing a negative pressed tightly against the sensitized paper that was left outside under the sun for several minutes to several hours depending upon the time of day, the time of year, the density of the negative, and many other variables.

McDermott and McGough found the cyanotype process intriguing and soon embraced other archaic photographic processes as well, including gum bichromate and palladium. Invented in the I850s and enjoying widespread use from 1895 onwards, the gum print combines potassium bichromate and gum arabic, which hardens upon exposure to light. The gum print has the advantage of variable color depending on the pigment added to the emulsion by the photographer. In the palladium process, which is similar to the Platinotype process patented in 1873, the pure platinum emulsion infuses the paper it is applied to, producing a particular graininess and a luminous tonal range, This process became a favorite for well-to-do “artistic photographers,” especially those within the Pictorialist movement. When the price of platinum sly-rocketed around the First World War, platinum prints virtually disappeared and the ubiquitous gelatin silver print became the most commonly processed image for the remainder of the century.

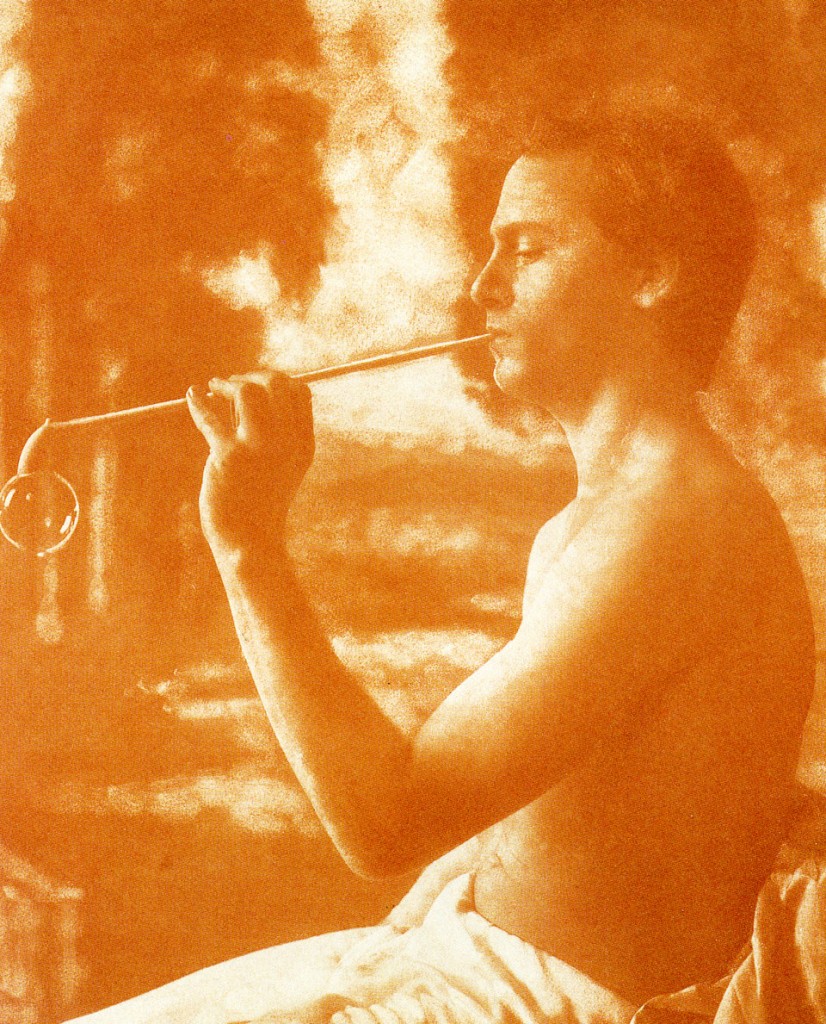

McDermott and McGough’s approach to photography has more than chemical processes in common with an earlier era. It was common for nineteenth-century photographers to have training in other art forms. Thomas Eakins, one of the most important American painters, for example, was an accomplished photographer and photographic inventor. Oscar Rejlander, although trained as a painter, made historic contributions to the establishment of photography as an art form. Rejlander ‘s lifelong experiments with the medium illustrate that the origins of both photographic seeing and photographic process in the nexus of art and science. Rejlander was interested in claiming grace, imagination, and subjectivity for a medium that was pulled toward scientific objectivity. Rejlander fell in and out of favor with critics, his photographs were often overtly theatrical, and his knowledge of art history is clearly evident in his elaborately staged photographs, with painterly quotations and actors fleshing out his allegorical scenes. Even a casual stroll through McDermott and McGough’s photographic world reveals the deep sympathies in sensibility that they share with Rejlander and other photographic ancestors such as Julia Margaret Cameron and F. Holland Day.

This volume opens with a pair of images suggesting domesticity and labor, followed by the 1990 palladium diptych As Much as a Pitcher will Contain, 1907/1990. Dual enamel vessels are simply presented sitting upon a tabletop, a wrinkled white sheet softly patterns the background. This image can be seen as referencing the two bodies, two souls, and two minds of our collaborators, sitting side by side, distinct, individual, yet united in proximity, sensibility, and utility. The pitcher is a receptacle to be filled and emptied, a vehicle for the storage and transportation or liquids, substances that conform to their containers. The pitcher is fully itself in form and function when it allows itself to be filled. The pitcher is receptive, passive yet collaborative, metaphorically analogous to early notions of photography, in that like the camera, the pitcher receives, captures, and contains vital fluids or essences. The diptych is used in this case, and in many others of McDermott and McGough’s photographic work, as a double self-portrait, the vessels offering themselves as receptive vehicles of light and spirit.

In the 1988 cyanotype Eighteenth-Century Salon as Reflected in a Nineteenth-Century Vase, 1907/1988, four distinct time periods are evoked: the old salon reflecting in the blown glass of the next century, photographed in the we twentieth century and pre-dated back to 1907. As any object, the vase is a product of its time; it not only speaks of its own cultural and aesthetic construction but also reflects back upon a pre-existing period. Its meaning in this photograph exists in its ability to contain and to reflect; the vase is empty of flowers, blossoms which speak directly to the bounty of the moment are absent. Paradoxically what is present is emptiness and loss; the blush of youth, the vitality of summer, the flowers of sensuality have long since faded. A distorted image of the past, a room filled with ghosts bends in the elegant flaws of the curved glass. Implicating the curved glass of the camera lens, this image asks the questions: What are the gifts of the present, and what have we lost of the past?

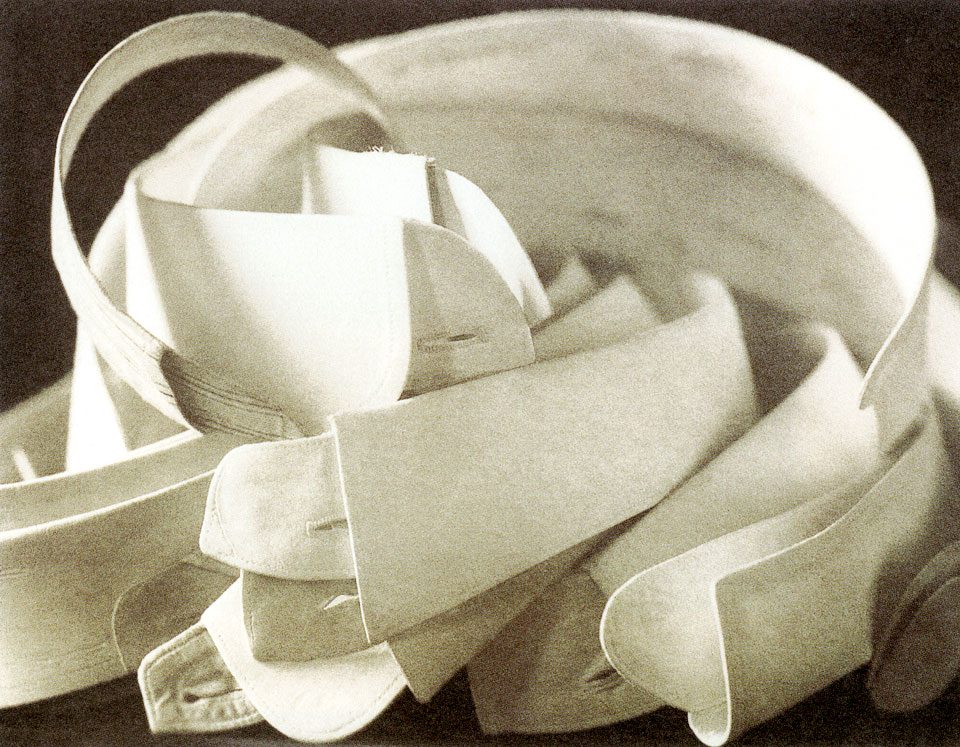

A recurring motif is the detachable collar, a turn-of-the-century fashion that allowed the wearer to attach a fresh collar to a shirt. In addition to the convenience for a man about town, this gentlemanly contrivance functions, usually to lift the head above the body, symbolically reaffirming the separation of mind over flesh, intelligence over physicality. Worn About the Neck Either for Cleanliness, Comfort, Protection or Ornament 1911/1991 is a vertical triptych of palladium prints, each image juxtaposing two starched white collars floating on a dark backdrop. Again these objects can be seen as stand-ins for McDermott and McGough, side by side, understated, minimal and proper, perfectly respectable, and elegantly presented In such a stark grid there is a suggestion of a taxonomic system beginning to be elaborated upon, as if pedigree could be discerned through the comparison of similar types. Yet there is something ghostly about these enigmatic objects, they are simultaneously familiar and foreign. Obviously the fellows that would sport such specific article of clothing are absent, lost to the relentless passage of time, as is the culture that would have its men of a certain class dress in this manner. Lost also culture of formality, where a delicate control of the body was cultivated and reinforced through a kind of refined bondage.

Like followers of nineteenth-century spiritualism, McDermott and McGough utilize photography in the attempt to contact the dead and to verify the presence of mysterious phenomena beyond the ordinary comprehension of a human being’s five senses. One could argue that this belief is fundamental to all of their images, but several in particular use the props, tropes, and gestures of Victorian occultism in of parlor tricks and amateur science. Experience of Equilibrium with Three Knives 1884/1990, Conductibility of Sound by Solid Bodies 1884/1990, and Mode of Formation of Rings of Smoke 1884/1990, palladium prints all, illustrate basic physical laws but imply greater forces at work. In the universe of McDermott and McGough, the boundary lines between science and metaphysics, between photography as an evidentiary medium and one that mystifies, are not drawn distinctly. Although the titles of the images pose to literally explain what occurs under the camera’s gaze, the performative aspect of the gestures remains enigmatic. As in the Roman Catholic Mass in which the bread and wine literally become the body and blood of Christ in the ritual of transubstantiation, there is something mysterious about these images wherein science and metaphysics conflate through the process of photography. A new and somewhat blasphemous Holy Trinity is implied: science and metaphysics beget photography, which is called to be the messenger and savior for both.

The Victorian tradition of photographing “Notable Men” is echoed in many of McDermott and McGough’s portraits. The Versailles portfolio of the preeminent French photographer Eugene Atget can be felt in the lonely drama of the salt prints A Lifelike Representation of a Female Figure from Behind 1865/1994, Fountain of Apollo 1865/1994, and Entrance to the Chateau de Sceaux 1865/1994. A pastiche of photographic references to Rejlander and Julia Margaret Cameron are at work in the religious and classical themes of Death of Marat 1907/1989, Virgil Reading to Augustus 1907/1989, and Children in Kindred Worship 1907/1989. McDermott and McGough also explore the homoeroticism of biblical themes in such images as Ascension of St. John the Baptist 1907/1989, and Study of a Crucifixion 1907/1989, and in doing so pay homage to F. Holland Day, the turn-of-the-century photographer. While these images may pay tribute to the legacies of these photographic pioneers, McDermott and McGough are not merely plagiarizing or mimicking their style in an attempt to create a patina of age. What would happen if a pair of nineteenth-century eyes gazed upon these photographs? Would the historical disruption be recognized or would the images fit seamlessly into the cognitive geography of the Victorian citizen’ Can photography’s power to indicate what has been be extended to what may have or should have been?

McDermott and McGough’s photographs are not documents in the traditional sense. It is no secret that these are historical fabrications. Their images depict a quiet, simple, unconflicted homo-social paradise, yet it must be admitted, that a certain madness must fuel the great lengths that they have gone to create this bucolic bubble, this pastoral picnic. McDermott and McGough’s photographs are domestic in a way that their paintings are public; the photographs calmly explore interiority, while the paintings make declarations. Yet it is the photographic work of this collaboration that literally, figuratively, and metaphorically encapsulates their experiments in time most profoundly. McDermott and McGough flit through time, visiting the early twentieth century most readily, moving with a bit more difficulty to the mid-nineteenth century, encountering more resistance as they attempt to travel further back. This is due in part to the diminishing archive that history provides, but also because the epoch-the span of McDermott and McGough ‘s obsession-is the one that straddles industrial and agrarian cultures. McDermott and McGough inhabit, photographically and performatively, a world that is at the edge of mass media, a world for a moment hesitating between the intimacy of the agrarian and the fragmentation of the industrial. Photography not only straddles the same era but also is the engine of the mechanical reproduction of images, and it is our incessant production and ceaseless consumption of images that so characterizes our era.

LIVING IN DUBLIN: STRADDLING THE CENTURIES

Leaving the Lower East Side, Brooklyn, and the Hudson River Valley to the gentrification and spiritual rot of the late-twentieth century, our time traveling duo has recently relocated their domicile to Dublin, Ireland, in hopes of finding a more receptive and less distracting culture. Dublin was founded millennia ago invading Norse Vikings bent on raiding the rich but decentralized Celtic culture. Lihn Dub, as it was originally called, means Black Pool, designating the area where the Rivers Liffey and Pobble meet. Although the Vikings were soon driven out, the site has been inhabited since, and if McDermott and McGough want to visit the past to communicate with ancestors then there are few more appropriate cities.

When I visited Ireland, McDermott and McGough had three bases of operation: a studio in the Temple Bar section of Dublin; a townhouse where they initially lived and is now used for guests, storage, and studio assistants; and a country house about twenty kilometers west of Dublin. The first time I called upon the country house, named Baldonnel, it was a typically cold, dark, and wet late-autumn afternoon. The sky was turgid. The road leading up to the house was gated and chained. Fallen tree trunks spaced at regular intervals blocked the passage of any wheeled vehicles; visitors must approach the house on foot or on horseback. After turning out of the heavily wooded path into a clearing. I encountered Baldonnel house as if the passage through the wood led from one time period to another. I became aware of how my perspective is, in every way, shaped by the technology I unconsciously utilize in my day-to-day existence. Had I been able to pull up to the house in a taxi, for example, I would not have had the tiny revelation of my contemplative stroll. I would not have noticed the thick and ancient moss hanging from the trees, nor the faraway, cacophony of a murder of crows, nor would I ha\’e tasted so deeply the sea and fog in the back of my throat. These sensory and visceral experiences would have been lost to the convenience of the late-twentieth century.

Though it was mid-afternoon, David McDermott greeted me at the imposing door in his nightclothes and stocking cap, explaining that French gentlemen in the eighteenth century only dressed to go out. Apologizing that Baldonnel house was not truly up and running as a time machine, he and Peter occupied only a portion of the house and estate. The general impression was of a place in transition, not only between inhabitants but between centuries as well. The process of de-modernizing had swept through the rooms; hidden cupboards had been reopened, recent plumbing removed, long-cold hearths rekindled. In the warmth of the wood stove, the kitchen was draped in the hand-washed laundry, clothing waiting to be mended and socks to be darned. Wooden crates full of apples just picked from the many trees surrounding Baldonnel were stacked in the corners of the kitchen. During the tour of the house, shutters in darkened studios were drawn exposing dozens of silhouette portraits that McDermott and McGough have been commissioned to paint. From a second floor window more laundry could be seen hanging on lines behind the coach house, vainly waiting for a drying sun.

Ireland, perhaps more than any other country, is identified by the particularly seductive combination of history and ethnicity; the so-called “heritage industry” is Ireland ‘s most important economic contributor, transforming Irish-ness and selling direct connection to the past. Like many ancient and historic cultures that rely on tourism, Ireland and Dublin in particular must cultivate a facade of historical authenticity in order to survive in the present. Crumbling structures, fading scripts, foggy legends, archaic dialects and such must be dug up, dusted off, resuscitated, and re-presented for the consuming sentimentality of the citizens of the present moment. Dublin is a site of historical pastiche; the medieval is neighbor to the Victorian, Edwardian windows look out upon council flats, pagan stones are the foundation for the cathedral, and Dunkin ‘ Donuts shares a cobbled walkway with “ye olde pub” with a name like The Drunkin ‘ Poet. The meaning of authenticity is apparently in the eye of the beholder, but one thing is certain: in a city like Dublin, the authentic present must include convincing simulations of the past.

On the surface, McDermott and McGough’s quixotic quest to synchronize the past and present it in one moment may seem sweetly naive and ultimately doomed, or perhaps they appear as elegant escape artists fleeing the complexities of contemporary culture. It is not a Luddite fanaticism that fires their utopic ideals, they are not interested in smashing the machines of the late-twentieth century, but prefer to revise and relive the past as an infectious bubble of gentility within the present, a bubble that will flit into the future. But there is no denying that their historical reconstruction is an embellished past, it seems not scarred by slavery, the Civil War, the genocide of Native Americans, industrial servitude, women’s second-class status, to mention just a few highlights of the “good old days” in America, This historical airbrushing makes for an odd feeling of depopulation in their photographs, as if they include as their subjects only those boys, artists, and aristocrats they would have loved.

The dominant atmosphere of their photographic time capsules is one of a pastoral meditation, of gentlemanly contemplation; McDermott and McGough are not historical thieves, they do not raid the past in service of the present. The bucolic nature of McDermott and McGough’s photographs, however, belies their historical aggression. Their photographs act as artifacts from a fantasized history of gay subculture in the late-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; they are not so much appropriating the past as making crucial additions to it. Donning Victorian and Edwardian guises- the gentleman scientist, the fraternal brother, the dabbler in the occult, the utopian communitarian, the explorer, and the dandy-McDermott and McGough “play” history and then document the results. The elaborate contrivances are self-evident, the contraptions shaky, sparks and smoke fly from the infernal machines of imagination, we know somehow that these photographs cannot be authentic, yet as if leaving our bodies and logic behind in the opium den, we arrive in the calming azure of their cyanotype dream.

Originally Published in McDermott and McGough: A History of Photography, Arena Editions, 1997