Man of the World

men of the world was a performance duo that I co-founded with Mathew Wilson in 1991. I met Matthew when I was teaching at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and was a member of an end-of-semester review board evaluating graduate student work. We were scheduled to meet Matthew in the maze-like hallway of one of many re-purposed downtown buildings that the School had acquired for studio spaces. Stepping off the elevator, we seated ourselves in chairs that appeared to have been provided for us. We sat for several minutes waiting in silence for the presentation to begin. A soft scratching noise from behind seemed to creep into our auditory consciousness, when we turned around there was a short bald man, bare-footed and swaddled in an oversized trench coat scribbling on the hallway wall with a pencil.

Getting up to observe more closely, we approached as he walked away dragging the pencil along the corridor wall moving into the dim interior of the building. Hooked, we followed a few steps behind. ‘This man is activating a secret world’, I thought to myself, remembering scenes from the Quay Brothers’ The Street of Crocodiles. Shadowy gestures appeared in several vestibules leading off the main corridor; one figure lay on the ground, a cloudburst of white powder across his shoulders obscured the head. Arriving back at our seats, after making a full circuit of the corridor, Mathew sat down and waited for us to respond.

It was for me, a moment of recognition. A strange recognition to be sure, because I hadn’t realized that I was looking for the thing I just witnessed. Which was a kind of performance that was formal, yet humane, that stayed on the right side of the line between the mysterious and the vague. An approach to performance that was theatrical but not sited in a theater, and that through simple gestures involving the human body, more specifically the male body, could be represented in ways that were unexplored.

I was interested in performance, but inarticulately dissatisfied with the current state of the practice with its stars like Karen Finley, Holly Hughes, and Spalding Gray, all of whom I admired but whose works were rooted in the conventions of theater in which the audience passively observed from comfortable seats. In Mathew Wilson’s gestures I saw the possibility of a way forward in performance, an approach that took it’s cues from artist heroes of the 1960s and 70s like Mendieta, Wilke, Schneeman, Acconci, Abramovic, Ono, Fluxus, while not shying from romantic or narrative elements.

I approached Mathew with the idea of collaborating. I thought we should get to know one another not in the usual way over coffee or drinks but through gesture and improvisation. I suggested we meet in an empty lot near my apartment. We agreed to bring a few simple tools / props and wear white shirts and ties. Surrounded by knee-high weeds, the lot was partially surfaced with a slab of concrete, the ghost of a floor from a long-since-demolished structure. We met, took off our shoes and socks, shook hands and stared at each other for a long time. I brought a chair, a metal bucket filled water and some white chalk. Mathew arrived with a briefcase and flowers. Instead of speaking, we wrote cryptic messages on the concrete. We played hopscotch. I washed his feet. He gave me flowers. I adjusted his tie. He measured my waist. We lay on our backs staring at the clouds. Although we did not realize it at the time, over the next hour we set the parameters for our decade long collaboration. People out walking their dogs or waiting at the bus stop had something new to look at that morning.

In response to our initial encounter, we composed some simple guidelines. We would only dress like office workers (white-collar drag, we called it). We would only perform during normal business hours in view of working people. Our actions would be unannounced. To curious onlookers we would never describe what we were doing as art but only reveal the title of the piece. We called ourselves men of the world and wrote a manifesto.

Gestures in the Paradise of the Ordinary

And two men faced each other. These were the holy days of obligation. We exchanged goods and services until the factories closed. We were ghost workers. We fantasized that history was no longer our only mediator. We learned much from our mothers and fathers. We wanted to clean them, dust them off, resuscitate them, and recover ourselves in the process. We attempted to reinvent poverty and violence. We harbored vague hopes to arouse ourselves and our fellow men from indifference. We were not simply circus freaks living in individual tents. We believed we could be cured by a single touch.

We believed we had no agenda.

The first official image / gesture took place on June 28, 1991 at Daley Plaza in Downtown Chicago, beginning at 8:30 in the morning. We traveled separately by subway, the first man to arrive chose a place to stand somewhere in the middle of the open plaza, while the second faced the other from a distance of approximately 50 feet. After this silent confrontation lasted for some minutes, each man bent down to open his briefcase to remove a gallon bottle of water and 12 clear plastic cups. With deliberation, the cups were set in an encircling clocklike pattern and filled to the brim with water. Returning to an upright position in the middle of a circle, we faced each other and waited.

After some minutes, one of us picked up a cup of water exited his circle to walk across the plaza. Upon entering the other man’s circle, he gently supported the back of the other man’s head while proffering the cup to his lips. After pouring the water into the other’s mouth, the man returned to his own circle to await reciprocation. This back and forth was to continue until all the water was consumed, signaling the end of the performance. Initially the gesture was gentle, nurturing, but becoming crueler in increments as the body began to reject the excess. But our inaugural performance was interrupted before completion by uniformed security. Asked what we were doing, we had no choice but to follow our newly instituted guidelines to state the title and offer no further explanation. “men exchanging fluids” we replied. Consternation. Then a shrug of the shoulders as the security men stated that although we must desist, one could get permission to use the plaza. We were directed to an office on the 12th floor where we obtained the proper forms.

One month later, on the same site we performed hour of the 100 flowers (we are jewels on a chain). Each man carried an aluminum bucket with 50 red carnations, attached to each stem was the typed message; ‘we are jewels on a chain’. After strolling through downtown in the early morning light we arrived at Daley Plaza and proceeded in an almost ritual fashion, to place one flower per granite square to make a 100 square grid. We then stood with our backs to the flowers for one hour. When anyone asked us what we were doing, we replied ‘it’s the hour of 100 flowers, please take a flower”. After the hour passed we turned to retrieve the remaining dozen flowers, embraced and exited.

men of the world continued to perform throughout the summer of 1991 in a variety of locations around Chicago, including the image / gestures 24 decisions to look, was mother silent?, the price of monuments and several iterations of men exchanging fluids. When we met to discuss performance ideas, we found easy agreement with the form and parameters and so we purposely kept our interpersonal relations minimal. We were, in a sense, becoming acquainted with one another solely through our interactions on the streets of Chicago. We were two men playing with the boundaries between public and private behavior, and in the process establishing new relationships with physical bodies to architectural and social space.

Walter Benjamin once stated that there wasn’t a park or town square in Europe that was not ruined by a monument of some sort. For much of the 19th and early 20th century, the erecting of monumental statuary was considered a civic duty for many American cities as well, and Chicago is no exception. Founding fathers, war heroes, and allegorical figures perched upon plinths and gazing down from the tops of victory columns besprinkle the city like so many random chess pieces. Over the years, through no fault of their own, these figures are loosed from their original narrative or ceremonial contexts, diminishing them to the merely decorative. men of the world decided to come to their temporary rescue. On September 27, 1991, armed with two buckets of soapy water, brushes and washcloths, men of the world approached various public monuments to give them a good scrubbing. Although not a single curious citizen inquired, we were prepared to respond to any questions with our own query ‘is father dirty?’.

Although I left for Los Angeles at the end of 1991 and Mathew stayed in Chicago we continued our collaboration actively throughout the 1990s. We were invited to performance festivals and by galleries and institutions to do our work on the streets of San Francisco, Seattle, Houston, Cleveland, Boston, Washington D.C, Toronto, and New York. We designed new actions for the specifics of each city.

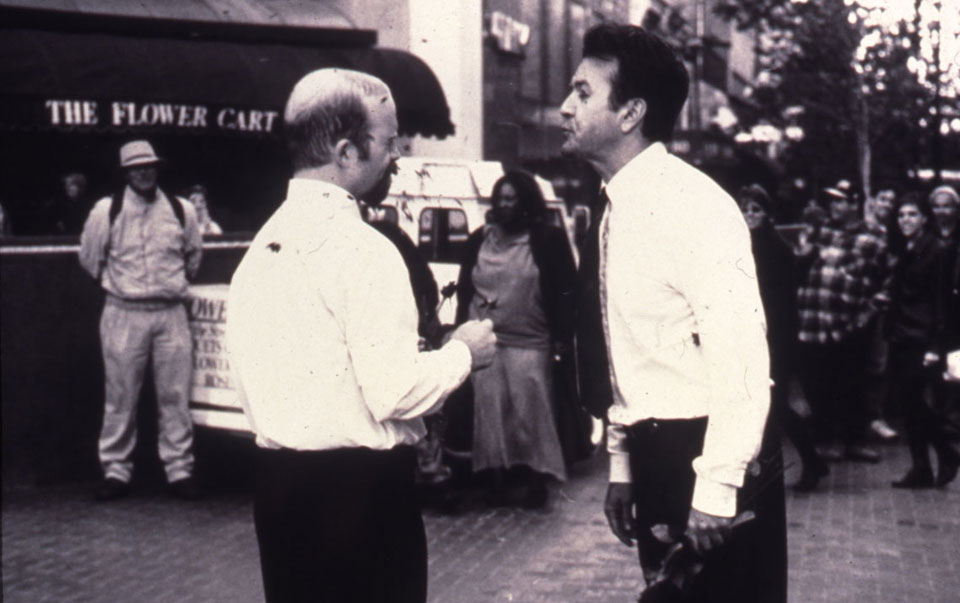

In 1996 men of the world participated in a group exhibition called Workspace that explored the esthetics of corporate culture. We performed 9 positions at the intersection of Market and Montgomery Streets in downtown San Francisco. At the top of each hour, beginning at 9am, we performed a single extended gesture. After each 10-minute gesture, we parted and met back again at a different corner of that intersection to perform the next gesture.

shake, groom, embrace, succeed, laugh, scold, dance, cradle: These actions unfolded each hour until 5pm when we performed spit. After each purchasing a bouquet of small budded roses at the corner flower stand, we faced one another for several minutes, flowers in hand. Eventually a single rose was proffered, the head of the rose was bitten off, chewed thoroughly and spat back in the face of the other. This action alternated between us until all of the roses were offered, consumed, and spat. By this time, people were pouring out of the surrounding office buildings on their way home from work. As if witnessing a schoolyard fight, several dozen encircled us and began shouting in surprise, disgust, and support, as our chomping and spitting became increasingly vehement. When finished our faces and white shirts were sprayed with pink spittle. We embraced and walked away together.

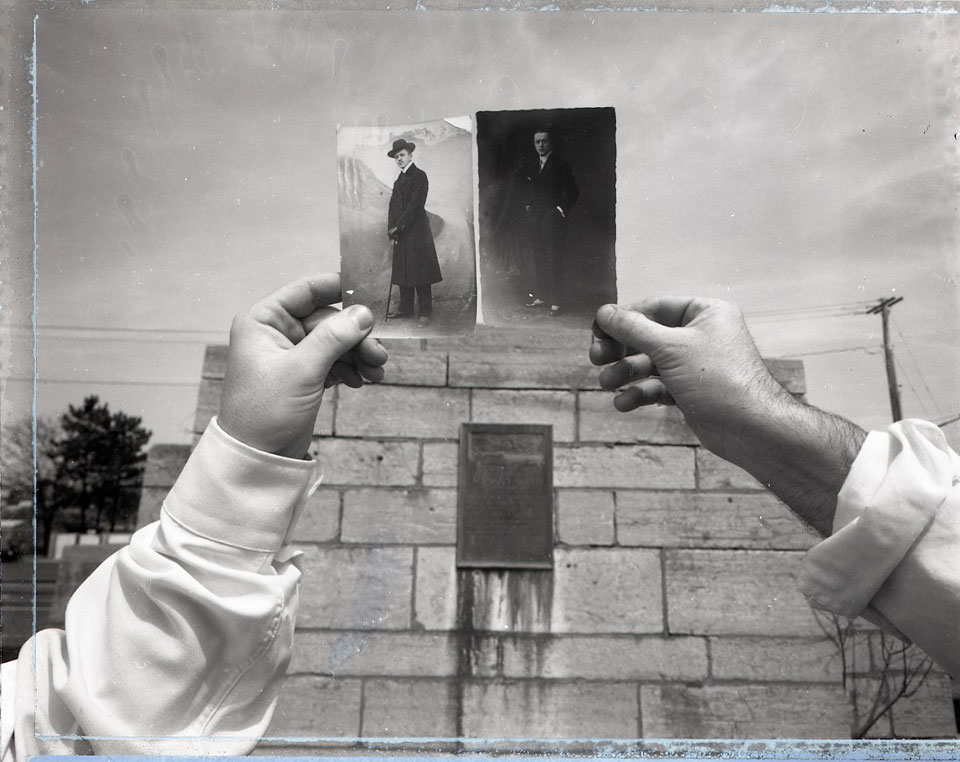

As with much of the history of performance art, photography plays an integral role in documenting the actions of men of the world. Mathew and I both studied photography as art students and were cognizant of how photography shapes, communicates, and in some ways replaces the meaning of the original gestures. Yes performance by definition is supposed to be an ephemeral art form, time-based, immaterial, and therefore transitory. But the documents of performance have become like holy relics. When we look at iconic performance images such as Chris Burden’s Transfixed, Beuys’ How to Explain Art to a Dead Hare, or Carolee Schneeman’s Interior Scroll, we tend not to think about how the photographic frame edits out non-essential details ensuring that the viewer can focus on the mythic symbolism. Beuys’ went so far as to desaturated his performance scenarios in anticipation of how they would translate into photographs.

men of the world did not document every performance but those that we did were chosen for their pictorial potential. We worked with many photographers over the years, most significantly the Scottish-born photographer Donald McGhie, and to a lesser extent Kyoshi Morikawa, Ken Rosenthal, and Annie Appel. Although we could not anticipate many of the variables of our actions once they were initiated on the street, we did pre-visualize sightlines, perspectives, and compositional possibilities. After strategizing with the photographer our basic directive was for the photographer to act like a tourist who just happened upon this enigmatic occurrence. A few exposures were made quickly and then the photographer would scurry off, for concern that the constant presence of the photographer would cast our action as some kind of publicity stunt or photographic assignment.

We attend museums and galleries anticipating some kind of engagement with images and objects. As we ascend grand staircases and pass through columned entrances of art museums, we are ceremonially prepared for this esthetic encounter. Even the industrial elevators and labyrinthine corridors of Chelsea’s gallery buildings provide a kind of ritual entrance into the halls of art. Like any art form, performance hopes to activate something in the viewer, yet men of the world’s actions, unfolding on the street as they did, were designed to skirt this preparatory experience, with the hope that we might induce unexpected wonder or at the very least mild surprise.

As might be imagined, anecdotes abound of mystified passersby attempting to decode men of the world’s actions. Anger and hostility were sometimes expressed in intimidating ways, although for the most part, we were met with bemusement and delight. But something often not considered with performance art is the sensual, emotional, and psychological experience of the performer himself, which can be deeply felt, creating sense memories as vivid as anything in ‘real’ life. I can report in precise detail the patterns of cracks on particular street corners of Cleveland. I can tell you what it feels like to have dozens of daisies rain upon you while standing in front of parking garage in Seattle. I have empirical evidence of real and symbolic vulnerability gathered while climbing high upon Civil War statuary in Washington D.C. as a Vietnam veteran harangues from below. I can describe the warmth and vitality of another man’s long embrace, the sweat beginning to wick through his white shirt while cars and trucks rumble past and assorted youth shout denunciations from the back of busses. I was a man of the world.