Lucy and her Neighbors

To become involved in a work of art entails, to be sure, the experiencing of detaching oneself from the world. But the work itself is also a vibrant, magical, and exemplary object which returns us to the world in some way more open and enriched. Susan Sontag – On Style

Lucy is my girl. I think about her all the time. Her name derives from the Latin word for light – Lux. Saint Lucy was a young Sicilian Christian living in the third century who was martyred when she refused to marry a pagan nobleman. Sentenced to be defiled in a brothel, legend has it that when the nobleman’s guards came to take her away she was immovable as a mountain. She suffered numerous tortures including having her eyes gouged out. Another version of the story has Lucy taking out her own eyes to offer them to her would-be husband who thought them beautiful. Saint Lucy is the patron saint of the blind, of eye disorders and the protector of sight. She is often portrayed in religious paintings holding a golden plate upon which her eyes rest. Her feast day is December 13, which in the Julian calendar was thought to be the shortest day of the year. In Swedish villages her feast day is celebrated with processions in which the youngest girl of each household wears a headdress of candles.

During the summer of 2010, when I was thinking about launching a website for writing about photography (mostly), I made lists of possible names, ‘Light Box’, ‘Caja de Luz’, ‘Incidental Light’ and many of which were unavailable. I would stay up late into the night purchasing numerous lame domain names (‘Luminous Flux’ anyone?). I was reading Maggie Nelson’s compelling meditation on the meaning of the color blue – Bluets – in which she invokes the legend of Saint Lucy. I remembered all those plates full of eyes: Lux, lucid, Lucy in the Sky, Camera Lucida, even. I was struck. Lucy acknowledges darkness and the coming of light.

The logo for my website is a detail from one of the earliest paintings of Saint Lucy which presents a regal Lucy holding a stem of a flower whose buds have been replaced by two eyes. I found the image online and discovered it was in the permanent collection of the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. I soon began making regular trips to visit her. After ascending the monumental steps that face the National Mall, to find Saint Lucy one must pass through the majestic central marble dome / oculus, stride west along a great corridor and then turn north, zigzagging through a warren of increasingly smaller rooms until arriving at Gallery 13 labeled, ‘North Italian Painting of the Late 15th Century’.

In addition to Saint Lucy, 17 additional paintings hang in Gallery 13. I never paid much attention to them until I thought about how much time my beloved symbol spent in their company. Who were Lucy’s neighbors? Did she like them? Were they worthy of her graceful presence? I was worried that Lucy might be bored, irritated or even offended by her neighbors. What was their deal? How did this assortment of paintings end up here in the first place?

14 of the 18 paintings were donated by Samuel H. Kress, the founder of a nationwide chain of five and dime stores in the early 20th century. Kress made his millions selling shoestrings and dishwashing detergent in small towns across America then spent his fortune amassing a distinctive collection of Renaissance masterpieces. His gift, among others, was the basis for the establishment of the National Gallery of Art in 1937. Saint Lucy then is, in effect, a foundational image for the institution itself.

Despite it’s historical importance, Gallery 13 is a lonely place, far from the Vermeers and Rembrandts that draw constant crowds. Excepting a small canvas by Mantegna, there are no celebrity painters in this modest gathering, but even with his reputation in Art History, celebrity is not a word you would associate with Mantegna. I once spent an entire afternoon – four hours – in Gallery 13, excepting one young man who sat for a few minutes, only 5 people strolled in who, after a quick scan, pivoted squeakily out to galleries with richer fruit. Guards peaked in every 5 minutes or so but graciously left me alone with my notepad and pen. Paintings do not come with instructions for looking; there is no suggested length of viewing time. Not that I was concerned, but I wondered how long I could stare at an artwork in a public place before appearing crazy. At what point will guards interrupt and escort me out, as if the power of a concentrated gaze might strip an image of its color.

I had committed myself to a day of deep and long looking. I wanted to find out what Lucy and her neighbors might reveal to me if I gave them a chance. I first checked in with Lucy. Made by Francesco Del Cossa in 1473, like most paintings of its time, Lucy is rendered in tempera on wood. Tempera color is extremely stable, much more so than oil paint which can darken and yellow over time, consequently Lucy’s lightly blushed cheeks and gray / green eyes are as vivid and luminous as they were when they were painted 542 years ago. Mirroring the style of Byzantine iconography she floats in a sea of gold leaf that would have shimmered and glowed in the candlelight illuminating a chapel interior. She holds a palm branch in her right hand, symbolizing victory over evil. Although partially camouflaged by the deep folds of her green robe, her left leg is raised in an unusual gesture, as if to prop up her hand proffering the flower petal eyes. Perhaps a result of a hasty restoration somewhere in the past, a thin smear of gold intrudes upon Lucy’s palm, compromising her perfection. Lucy’s gaze is averted toward the disembodied eyes that uncannily stare out at us. The color of her two sets of eyes does not match.

Absurd as it is to project 21st century perception onto an image that inhabited a world that was more attuned to gesture than facial expression, it is difficult to read Lucy’s; she looks a bit repulsed by the strange blossoms, as if she is doubtful of God’s restoration of her sight. In the Middle Ages and well into the Renaissance, gestures were understood as an expression of interiority. Society was not only rigidly organized but also highly ritualized. This included requisite bowing and scraping before superiors of course, but also how one stood in church or ladled soup into one’s mouth would be indicative of the body as the ‘prism of the soul’. For a vastly illiterate society, the positions and gestures of painted figures were instructional tools illustrating a precise rhetoric of body language.

The paintings in this room are virtuosic, formal and reverent, everything that my world is not. I want to animate these images and have them animate me in return, not through religious faith but through their material presence, miraculously preserved 500 years in their future. I was raised Catholic so these icons are familiar but to recognize is not the same as to know. Maybe it has something to do with what Sontag writes in ‘On Style’ “The knowledge we gain through art is an experience of the form or style or knowing something, rather than a knowledge of something (like a fact or moral judgment) in itself.” I feel as if I am on a pilgrimage toward a vague transcendence, as if looking may have its own rewards.

Beginning with Lucy I make several clockwise circuits around the room, appreciating color and gesture, faces of grief and serenity, before slowing down in front of three adjacent Madonna and Child paintings hanging in the middle of the east wall. Painted in 1460 by the son of a shoemaker Cosme Tura, the first portrays the pair in a garden representing Eden. In an acknowledgment of Christ’s human origin, the child sleeps between Mary’s parted legs, his head supported by her knee. Sleep was thought ‘the brother of death’, so the napping child prefigures Christ’s sacrifice, a large rose blooms behind the pair like a bloody aura. And if that weren’t enough foreshadowing, Mary sits upon a stone sarcophagus. One of Tura’s esthetic idiosyncrasies was the manner in which he elongated human anatomy for expressive purposes. The Madonna’s skull seems to inflate under her lacey headscarf and her impossibly long fingers shape a Gothic arch to hover over her sleeping child.

Carlo Crivelli, Madonna and Child Enthroned with a Donor, tempera on panel, 1470. Left detail, right full image.

Hanging to the right of Tura’s is Carlo Crivelli’s Madonna and Child Enthroned with a Donor from 1470. It is a royal depiction of the sacred duo, seated as they are upon an elaborate throne. Despite his patronage, the Donor in question is pictured as a diminished supplicant at the foot of the throne, painted in a cursory, cartoon-like way, as if Crivelli resented having to include him in his otherwise exquisite image. Mary does not meet our gaze, seeming distracted or disinterested. Christ himself is oddly misshapen, his back asymmetrically hunched up as he were an escapee from a Medieval sideshow. Perhaps this indicates the burden of the large apple he is holding, a reminder of our fall from grace and the promise of redemption through his personal sacrifice. The explicit or implied intimacy between mother and child prompted Saint Augustine to describe Christ as the ‘Infant Spouse’. And as Leo Steinberg has taught us in The Sexuality of Christ, Mary’s left hand gestures, as it often does, toward Christ’s genitalia, emphasizing his humanity that he is, in fact, of us.

On the south wall the twinned portraits of a man and a woman are hung so as to face one another. Painted by Ercole de’ Roberti in 1474, of all the human likenesses in this room, only these are based upon observation and familiarity with actual persons. Giovanni II Bentivoglio and Ginerva Bentivoglio make an elegant couple, he in his vivid red cap and perfectly cut light brown locks looks across to his wife in her brocaded and bejeweled gown, her blond hair provides support for the burst of brittle lace cascading down to her left shoulder. Both are pictured in front of a discretely parted curtain that reveals the crenellated walls protecting the city of Bologna and the Northern Italian landscape fading off to a bluish horizon. Giovanni’s rule over Bologna was notable not only for his generous support for the arts but also for his cruelty. He once tortured a fortuneteller because he was not pleased with his predictions, yet Ginerva looks pretty good considering she bore Giovanni 16 children.

Left, Andrea Mantegna, The Infant Savior, tempera on canvas, 1460. Right, Ercole de Roberti, The Wife of Hasdrubal and her Children, tempera on panel, 1490

Still on the south wall but on the other side of the entrance and the inscrutable guard, is a small painting by Andrea Mantegna, The Infant Savior. Although Mantegna was one of the first Italian artists to use oil paint, this is still tempera but rendered on canvas instead of panel, an unusual choice in 1460. This image is unlike any other in this room for its smoky, smudgy, moody quality. This is partially due to a varnish that has darkened over time, but also because it is painted on canvas. The figure is less hard edged, less graphic, less iconic, suggesting a three dimensionality and corporeality that tempera on panel could not achieve. Here Christ appears to be emanating from an inchoate landscape that suggests desolation or maybe the limbo where souls languished before his opened the gates of heaven with his sacrifice. He is without the succor of his mother, his face is shadowed, his expression determined, betraying no innocence. Here is a child fully aware of the horror that awaits him, yet he moves toward it without hesitation.

The west wall has several paintings that reference well-known biblical or historical subjects, but are imagined with such narrative complexity and gestural drama, as to compete with the most existential and surreal stagings of the 20th century. The first, and perhaps the strangest is The Wife of Hasdrubal and Her Children, painted by Ercole de’ Roberti in 1490. Hasdrubal was a Carthaginian military leader who surrendered to the Romans in 146 B.C., resulting in the complete destruction of Carthage and the end of the Third Punic War. Hasdrubal’s wife (unnamed) was so ashamed of her husband’s cowardice and humiliation that she threw herself and their sons into the flames engulfing the Temple of Eshmoun (the Phoenician god of healing). Roberti has pictured the enraged wife in mid-stride atop the temple’s rubble, her face contorted with emotion as if she is proclaiming her disgust to the entire world. She grapples with her naked children who appear to struggle to free themselves from their mother’s madness. The drama and violence of this animated scenario is enhanced by the red backdrop that appears as if it were hung there for the express purpose of theatrically isolating the figures from the chaos surrounding them.

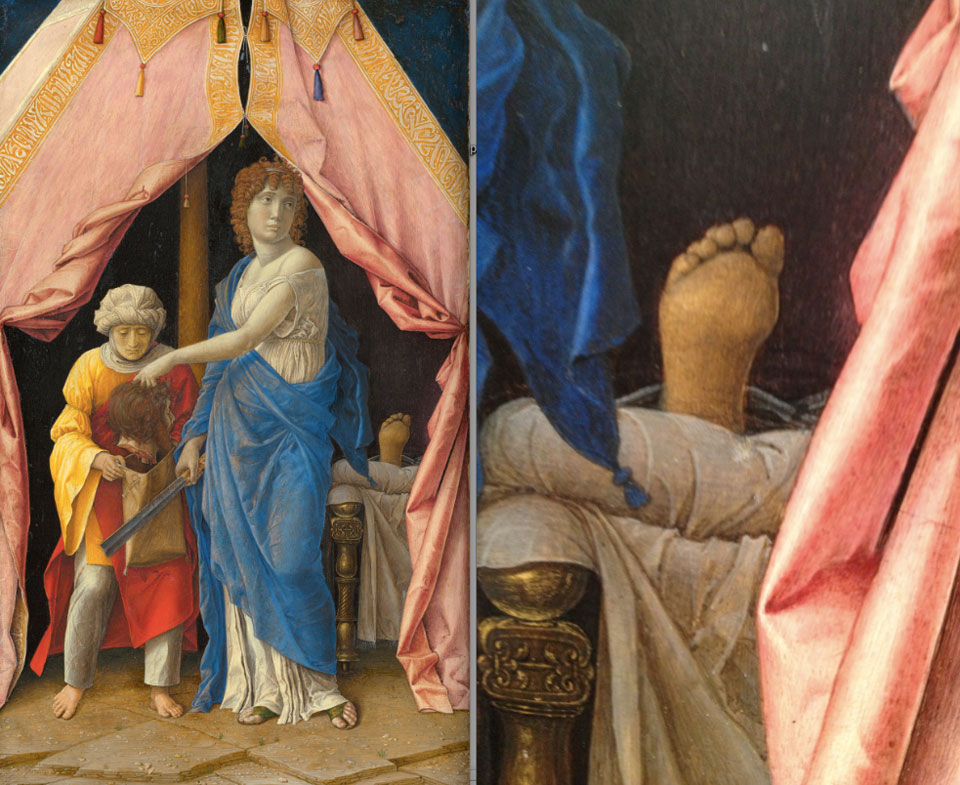

A couple of frames down from Hasdrubal’s Wife is another Mantegna painted in 1495, this time more conventionally, on panel. It portrays the perennial Old Testament favorite (if apocryphal) Judith with the Head of Holofernes. Holofernes was an Assyrian general about to invade and destroy Judith’s home, the Israelite city of Bethulia. Judith exploited his lust for her, visiting him in his tent, getting him drunk and decapitating him when he passed out. The old school righteous violence and heroism of Judith’s act contrasts sharply with New Testament passivity as embodied by Saint Lucy, who, as far as we know, never attempted to thwart her suitor and instead accepted her martyrdom without complaint. Mantegna’s version is small by today’s standards, barely 12 inches tall and 7 inches wide, yet it commands attention from any angle. In spite of her recent act, Judith stands serenely like a Renaissance supermodel, swathed in blue and white, her hand still tangled in Holofernes hair as she is about to drop the severed head into a sack held by her elderly servant. A forlorn foot in the tent’s darkened interior signifies the general’s corpse. The scene is transformed into a sexual proscenium by the pink drapery that part like curtains of labia to reveal the potent darkness of the vulval vestibule.

The last painting on the west wall is Saint Apollonia Destroys a Pagan Idol by Giovanni de’ Alemagna (or German John as he would be called today in casual English). While not as exquisitely painted as Hasdrubal’s Wife or Judith, the image has a vertical theatricality worthy of our attention. Apollonia was an early manifestation of what became known (like Lucy) as the ‘virgin martyrs’, those young women who chose death over defilement or renouncing their faith. Apollonia was a citizen of Alexandria in the third century, who during a particularly brutal anti-Christian purge, was tortured by having all of her teeth pulled or knocked out. Not surprisingly she is the patron saint of dentistry and tooth troubles. Medieval churches competed vigorously for possession of her alleged dental relics.

The painting is neither luminous nor subtle, yet Apolloinia’s determination as she climbs the tall ladder with a sledgehammer over her right shoulder is, in it’s own way, an impressive display of iconoclasm. A healthy cross-section of Alexandria’s citizenry have arrived to observe three women fellow co-conspirators steady the ladder as Apollonia makes her way up to the unidentified pagan idol. The male figure is naked and holds some kind of floral arrangement near his genitals. He is oblivious to his fully clothed and chaste nemesis rising from below to topple him from his heathen plinth.

This brings us full circle back to the north wall, back to Saint Lucy. Two paintings hang to Lucy’s right. Saint Florian, the patron saint of chimney sweeps, soap makers and firefighters and a rather gruesome crucifixion. All three were painted by Francesco Del Cossa in 1473 and are remnants of a dismembered polyptych, commissioned by Floriano Griffoni for his private chapel in Bologna. Florian was Griffoni’s patron saint and Saint Lucy was rendered in honor of his deceased first wife, Lucia. Florian looks upon his sword with as much ambivalence as Lucy does her own eyes, and mirroring Lucy’s gesture, Florian’s leg is also propped up in an unusual position.

Francesco del Cossa, left, Saint Florian, right, The Crucifixion, both tempera on panel, 1473 / 1474

Cossa’s Crucifixion is a simple circular composition of three figures set atop a painted altar. The faces of the witnesses are studies of disfiguring grief. Blood flows down from Christ’s pierced feet dripping over a skull like unrelenting tears. This mutilated and broken body has been the dominating icon of Western culture for two millennia. Much of the beauty and terror of history, all of that which we consider sinful or pure emanates from this portal. Every image in this room was conceived, commissioned, collected, and displayed to honor, teach and insist upon the dogma of this faith. Each of these paintings, no matter how delicate, is in orbit around this dark star of cruelty.

It has been decades since I rejected the tenets of Catholicism; I do not have a shred of Christianity left in me. Yet I do believe in the power of images. In 1998 I visited the Convent of San Marco in Florence to see Fra Angelico’s frescoes, scenes from the life and Passion of Christ painted in the moist plaster walls of diminutive rooms in the 1430’s and 1440’s. In effect these paintings were created for the contemplation of a single monk inhabiting each cell. Upon entering one is compelled to bow to avoid hitting one’s head and perhaps there was something in that bow that opened a part of me that I thought long closed. With each successive bow and straightening up again in order to behold these images, my body became involuntarily ritualized. I experienced the frescoes like visual whispers of the sanctified, intimations of secret things. I wept openly. Here I was, this late 20th century Irish American from a working class family standing alone in a cell adorned with an image embedded in the walls a half a millennia ago, and I felt as if it were painted for me. This historical bridge, fervently crafted as it was from pigment and plaster, reached me on the other side of time and belief. On some fundamental level, I have wanted nothing else in life but that feeling.

Today I bow to Saint Lucy, not in supplication but in gratitude. I am thankful for the strange, random and circuitous path that brought her to this quiet and elegant room. I bless the artist Francesco Cossa who fashioned her; I nod to the often cruel and self-serving patron who commissioned her and the varied unknown Italian aristocrats that protected her through the centuries. I throw a shout out to the American capitalist who acquired her out of love or greed or both and lastly I praise the institution that preserves and houses her and her complicated but never boring neighbors.