Finding Photographs

Early on, I learned to disguise myself in words, which were really clouds.

Walter Benjamin, ‘Berlin Childhood around 1900’

Running out the door to bring my son to his baseball game I usually grab something to read in those long and irregular moments between pitches and innings. This day I pulled a paperback copy of Walter Benjamin’s Berlin Childhood around 1900 from the bookcase. I hadn’t looked at it in years and although I remember thinking it lovely and provocative, I almost pushed the spine back in snug among its companions because it seemed pretentious to be reading such a thing among the enthusiastic parents shouting words of encouragement on a Saturday morning. But really, who would care?

The baseball field claims modest territory between the large green spaces of a private school, the utilitarian asphalt playground of a public school and the carefully groomed grounds of a Roman Catholic cathedral. There must have been a wedding or a funeral that morning because the cathedral’s bells began ringing at 10am while my son was at bat. He swung and missed a couple of times but walked to first base as the fourth ball sailed high over the catcher’s mitt. The bells continued to resound for a full 15 minutes while a couple of dozen 9 and 10 year old boys pitched, swung, ran, and cheered under the cloudless dome of blue.

I remembered the bells of Saint James church in Medford, Massachusetts where I served as an altar boy and where I also attended the adjacent parish school. In seventh grade I began to nurture two serious crushes that remained unresolved and unrequited before I went to high school. The focus of my affections embodied the binary of female identity that was the cultural norm of that time and place, the virgin and the vixen. Conveniently, the virginal was named Virginia, while the bad girl purred her name Rosanna. Rosanna’s hair bounced in a short bob and bangs that drifted below her often arched eyebrows. In wet weather she wore a shiny white raincoat with big black polka dots that she cinched tightly around her waist emphasizing her budding breasts. Rosanna had scarring on both cheeks as if she had survived a fire. No one had the nerve to ask her what happened but it was the subject of endless whispered speculation. Some girls thought her roughened skin made her hideous, monstrous, but I think it was Rosanne’s unapologetic boldness that intimidated us most. That Rosanne supported me to be the ‘Humor Editor’ of our school publication was the highlight of my early adolescence.

Virginia was not fashionable and was, as far as I could tell, completely asexual. She was a bit pudgy and her Catholic School uniform was a hand-me-down from her older sister. She was the smartest person in the class and could effortlessly answer questions on any subject that Sister John the Baptist interrogated us with. I always came in second place to Virginia’s first in school-wide spelling bee competitions, but I did not mind since I got to stand next to her in front of the class, my fidgeting hands leaving humid imprints on the blackboard behind me. Every spring a vote would be taken for the girl whose life and manner most mirrored the Virgin Mary. No one was surprised that it was Virginia who led the procession from the school to the church after her crowning as Queen of the May. While the bells rang, we sang along with the clanging melody ‘Oh Mary we crown thee with blossoms today! Queen of the angels, Queen of the May’. Feeling both pious and lustful, I gazed upon Virginia’s pale and cherubic face with confused fervency.

Reading Walter Benjamin I am reminded that history happens everywhere and that childhood is a rich chronology of often minor events that can have unexpected consequences years later. I wonder what my son might remember of his early years. Will he remember the bells ringing while he swung a baseball bat on a perfect spring morning? I cannot recall my father accompanying me to baseball games but I can instantly summon vivid images of the whiskered stubble sprouting like tiny licorice plugs from the folds in his neck. He always smelled of cigarettes and often of whiskey and beer. At the sudden and sharp crack of the bat I raise my eyes to watch a scuffed white ball spinning high in the air only to come down, miraculously, in the first baseman’s glove. The parents, fellow teammates and the first baseman himself, exclaim wildly. As the game proceeds I take a few pictures with my iPhone while listening to the very specific chatter of baseball, ‘good eye!’, ‘protect the plate!’, and ‘look alive!’.

Observing this almost Normal Rockwell-like scene, you wouldn’t guess that Baltimore had been under curfew for the past week and that the National Guard occupied parts of the city. Since Freddie Gray died in police custody on April 19, the populace had been consumed by inflamed passions. Like Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner and Michael Brown, Freddie Gray became an instant symbol of state violence against black bodies. The Baltimore Police attempted to describe his injuries as ‘self-inflicted’. Everyone else with any sense applied the more accurate term ‘murder’. Political persuasions are revealed by the choice of words used to describe the unfolding events of the last 10 days; is it ‘Uprising’ or ‘Riot’, ‘Civil Unrest’ or ‘Anarchy’, ‘Protesters’ or ‘Thugs’? Language and representation are (as they should be) as contentious as the confrontations between citizens and police.

Later this day I will bring my son to the protest in front of City Hall. We will chant ‘I can’t breathe’ and ‘No justice, no peace’. He attends a Baltimore public school and although he is only 9 years old, he is quite aware of the issues of racism and poverty in our city. He is excited to join the throng. All week we had been talking about what was happening on the streets. We watched the news, read online reports, and received incoming personal observations from the social media feeds of friends participating in marches and demonstrations. My wife and I are both teachers in public institutions and we have facilitated heated classroom discussions. But my son is white and I don’t have to warn him about the police and on this lovely morning in the leafy northern end of the city there are no fires or looted CVS stores, or riot-geared National Guard. The adults, many of whom send their kids to private school, gather behind the chain link backstop behind home plate and politely discuss the ‘terrible situation’ while uttering platitudes of upper middle-class liberalism. Queried if they intend to participate in any of the protests, they demure, speaking vaguely about appointments and wanting to avoid violence.

Walter Benjamin, tragic hero of left-leaning intellectuals, describes his childhood immersed in luxurious surroundings, exploring the theatrical shadows of colonnaded interior gardens, running his fingers over the haptic richness of tapestries, brass, silver and silk. Three decades later, the onslaught of National Socialism would sweep away the privileged illusions of assimilated bourgeois Jews, and Benjamin, suffocating in a vortex of despair would take his own life in 1940. Not surprisingly, Benjamin’s philosophy, or sensibility, had an apocalyptic inclination. This apocalyptic view is represented powerfully in his description of ‘The Angel of History’ who understands history not as a series of events but as a single ongoing catastrophe. While studying the past Benjamin was always in search of traces of what was to come. He looked for the future in the past as if believing that what was could somehow could communicate with what would be. By secreting charged images, objects, and textual messages that might be discovered among the shards of time, history attempts to warn us of our unresolved conflicts and contradictions.

‘Finds are for children, what victories are for adults’ writes Benjamin in Berlin Childhood. I don’t know what victories I have had as an adult. I don’t think in terms of winning and losing, instead my binary thinking quavers somewhere between skepticism and ambivalence. But I am still acquainted with the thrill of an unexpected find. Sitting back down and opening Berlin Childhood while my son’s game meandered on, I opened the book to previously unnoticed photograph tucked deep in the gutter between pages. The small black and white picture looked familiar and foreign simultaneously. I must have found it at a flea market and put it Benjamin’s book some years ago but could not remember doing so.

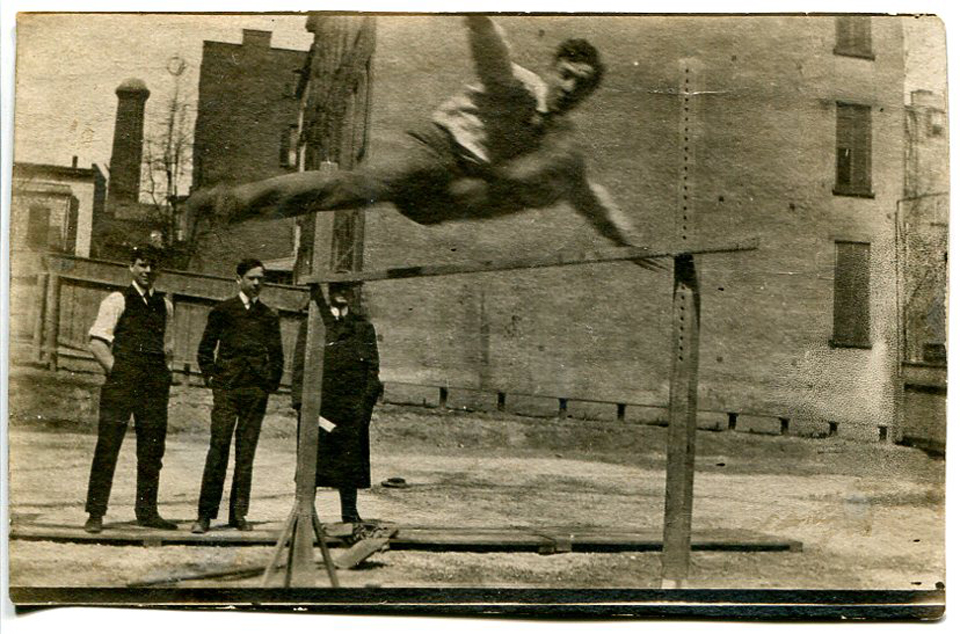

A bit of shredded gray paper stuck to the back of the photograph suggests it had been torn from a family album. The image is banal and mysterious, showing a young man in the foreground hurdling over a wooden bar while three men observe from behind. There is a kind of descending order of formality in the men’s attire, the first of the observers on the right is fully clothed in topcoat and hat, the next man has shed his topcoat but sports a jacket, while the next stands with rolled up sleeves and vest, the jacket-less jumper stares at the camera as he aerodynamically stretches out his arms while folding his left leg under his torso, heel to genitals.

It is an urban scene; the men occupy an empty lot, a smokestack looms in the distance. It could be any industrialized urban center in Europe or the United States circa 1920. As if to defy the stabilizing pleasures of a horizon line, the majority of the image is filled in by a collage of brick surfaces. It is a theater without exits. Unanchored from other photographs that may have narratively or geographically contextualized its enigmatic assertiveness, the photograph exemplifies the inherent surrealism of photography. Specific and inscrutable, it is a sign without a secure meaning, and for a moment I imagined this snapshot to be a study made by the proto-Surrealist painter Giorgio de Chirico.

Finding photographs is a different adventure than taking photographs. Nostalgia and irony are the first obstacles one must overcome in seeking deeper mysteries. The yellowing paper image of the hurdler and his friends is barely 3 x 4 inches yet it has survived for almost a century. Not only was it mounted in a family album, it was then carefully separated from that album by someone who thought it evocative enough to send into the world to fend for itself as a fragile image / object, then traded among strangers leading to a possible resurrection in the future. That premonition or act of faith was a gift to me and I mouthed a silent thanks on that complicated day in Baltimore 2015.

The baseball game is winding down as I pull out my phone to check Facebook and Instagram for any new images or reports of what was happening in Baltimore. I madly scroll through my feeds of updated profile pictures, mundane landscapes parroting the sublime via digital filters, and silly Gifs of malicious politicians. My thumb moves like an inchworm on crack searching for something that might temporarily halt my attention. Usually I desire content that is vaguely interesting but does not require actual engagement or risk. But today there is a surfeit of engaging posts, images and commentary about the Freddie Gray uprising. I am grateful that I do not have to rely on the warped sensationalism of CNN or other corporate entities. Josh Sinn, a young photographer who spends a lot of his time roving the streets of Baltimore has particularly lively images. In late afternoon slanting light a beautiful young man stops his bike to brandish an upraised fist. In the softened blur of the background he is followed by others with arms raised, perhaps shouting ‘Hands up, don’t shoot’ in honor of Michael Brown. The young man’s face is open, non-judgmental yet unyielding as if to ask ‘Knowing what you know, how can you not be my ally?’

Can a single photograph still have the power to delay us in our obsessive desire to see more? What is photography when there is no object, no paper artifact? Will the face of that young man haunt someone in the future? Will anyone find his unswerving gaze and raised fist inserted between the pages of an unlikely memoir? Will it be found in some pixelated cellar of a long-defunct Internet? Will he still need allies?

A young man raises his fist in solidarity during a protest march following the death of Freddie Grey in the Sandtown-Winchester neighborhood of Baltimore. Photograph by Josh Sinn, April 21, 2015