Trickle-Down Counter Culture

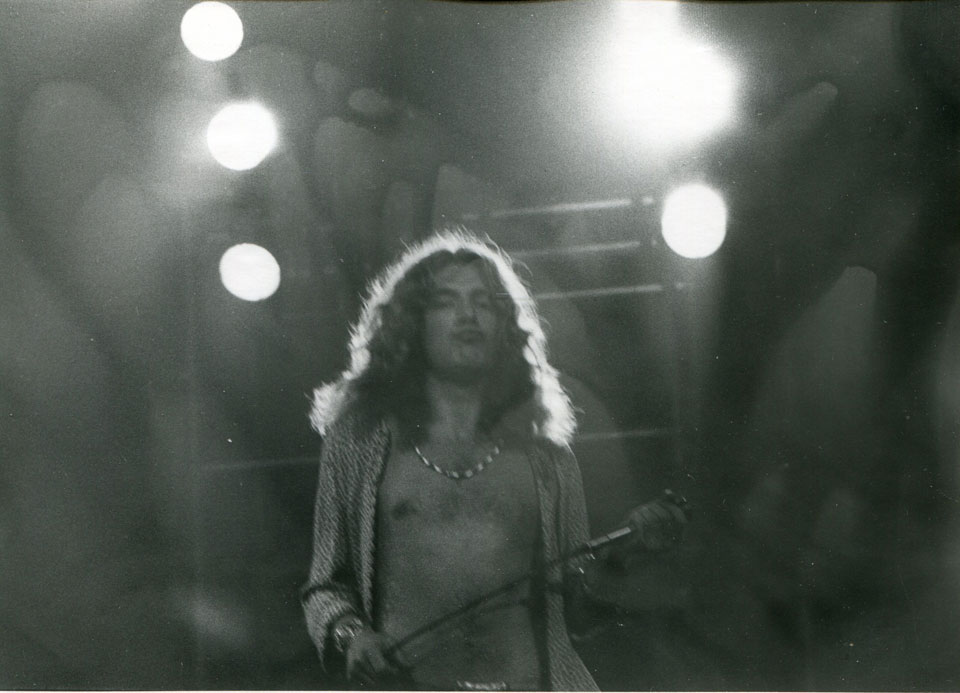

The first time I ever used a camera, I mean a real camera, not a Brownie or Instamatic, I was standing in a tight crowd of teenagers surging toward the stage as Led Zeppelin’s guitarist Jimmy Page kicked off the concert with the stuttering riff of ‘Immigrant Song’. I was trying to steady my hand so I could focus on the halo of backlit hair enveloping the wailing Robert Plant.

Just days before, a self-described media activist who looked exactly like Cat Stevens had pulled a camera out of his shoulder bag and asked me if I wanted to learn how to use it. I mentioned that I had tickets to Led Zeppelin that weekend. He gave me two rolls of Tri-X and entrusted me with his Canon FTb equipped with a 200mm lens, saying, “Bring it back and I will show you how to develop the film and print the pictures.” This image of Robert Plant is from the introductory printing session. The negative is thin, underexposed, and to prevent the image from being swallowed up in darkness, I pulled the print out of the developing bath too soon resulting in that mottled, underdeveloped look.

Despite its imperfections this photograph is proof that I worshipped at the foot of their altar, that I was baptized in the sweat spritzing from Robert Plant’s golden locks. The technical flaws are also an essential part of its documentary truth. The streakiness of the image speaks to the novice’s impatience. There are no true black tones in the picture to provide depth and drama, and instead of a glistening expanse of skin, Robert Plant’s torso appears murky and unsexy. But it didn’t matter. Like any rebellious teenager of that era, I had scribbled my share of heartfelt poems and Dylan-esque songs, but while holding the camera in my hands I felt transformed, I had some idea of how I might be in the world, how I could proceed. I had become a participant observer.

The mechanical and technical aspects of photography provided cover for a working class kid with artistic tendencies. Because the tools and processes involved glass and metal, optics and mechanics and noxious chemicals doled out in carefully measured batches, photography seemed manly enough.

A concern for manliness may seem odd for someone whose hair was well down to his shoulders but it was mixed message kind of world. I lived a mere five miles from centers of youthful rebellion of Harvard Square, Boston Common, and dozens of university campuses where long-haired and radicalized students were challenging the war in Viet Nam and myriad other injustices, creating what was termed the ‘counter-culture’.

Although I couldn’t wait to be old enough to be a hippie, to participate in the creation of a liberated egalitarian society, there was an underlying anxiety of inauthenticity. I didn’t know any actual hippies or campus radicals. My friends and I used to joke that the only way we would be going to Harvard was as janitors. But I gleaned what I could from magazines, album covers and revolutionary literature. Without asking his permission I converted my father’s U.S. Marine jacket into an anti-war fashion statement by pinning to its back an American Flag with a peace sign made of electrical tape. Unable to fund an actual fringed suede jacket like the one Neil Young was wearing in the poster on my bedroom wall, I bought a Naugahyde version and hoped I could get away with it. “We’ve got to get ourselves back to the garden’, Joni Mitchell pleaded in her ode to Woodstock. Would Joni accept me as one of her own?

Canada, jail or Vietnam: these were our impending choices and we argued the repercussions of each option. We heard that acting crazy or claiming to be a homosexual apparently wouldn’t exempt you anymore. By the early 1970s with the war winding down and the military draft all but suspended, our very real fear of conscription began to fade. To be sure, there were other outrages to protest: the overthrow of Allende in Chile, the gun battles at Wounded Knee between activists in the American Indian Movement and the FBI. But when in 1974 the demonic President Richard Nixon resigned in scandal, our bête-noir had become a pathetic, puffy, shell of a man, stuttering in his historic embarrassment. Among young people the angry urgency and thrill of rebellion had tempered into amorphous ideas of living ‘alternatively’. I felt like I missed the boat for true righteous indignation.

In high school we had access to any kind of drug we wanted, which I, for one, consumed greedily although I never experienced the utopic optimism, the oft-trumpeted ‘freeing of the mind’ promised by Timothy Leary. With four thousand students, Medford High School was as distant from a communal paradise as one could get. Its main function, as far as I could tell, was to serve as a giant warehouse of disgruntled adolescents, a Costco of disaffection. We got the drugs and the long hair but none of the liberation.

The student population self-selected into tribal identities: the freaks, greasers, jocks, art kids, and intellectuals. My tribe fancied themselves high school revolutionaries. We published ‘underground’ newspapers with names like ‘Breathe Free’ and ‘New Dawn’. I published anti-war, anti-everything articles under the pseudonym L.D.V. that stood for Leonardo de Vodka. Our fellow high school students treated us with disdain or outright hostility. I considered this derision a badge of honor, proof of my subversive power, until confronted in the hallways but thugs flinging the epithets “hippie, commie, faggots’ (where do we learn to play our roles so authentically?), which would send me scurrying like a frightened rabbit.

We were virtually asexual; very little romantic intrigue compromised our solidarity. There was no hint of Larry Clark’s depravity or Nan Goldin’s emotional excesses for me to photograph. We had created a mostly chaste, non-violent bubble for ourselves, a disorderly array of escapists, motivated by an unarticulated desire for a prelapsarian Eden. With basic picnic supplies and whatever crumbly twigs of marijuana we could cobble together, my friends and I passed much of our time traipsing the scruffy pine, oak and birch woods just north and west of Boston.

Walden Pond was an attraction for us, not that we knew anything about American Transcendentalism, we just liked walking in the footsteps of Henry David Thoreau. Kicking aside rusting beer cans we would spread out in pairs, threes or solo into the homely woods, finding paths that led to higher ground, sharing jokes and brief moments of wonderment and confusion. I don’t remember ever discussing careers or college ambitions. We rarely discussed books except for The Little Prince, the Lord of the Rings, the Chronicles of Narnia or The Teachings of Don Juan by Carlos Castaneda. Mostly we shared a love for music and an amorphous vision to live uniquely. Frequently we sang ‘Over the Rainbow’ atop of rocky promontories.

We operated under the default belief that we were fresh citizens of the new world that was organically bubbling up from youth culture. We were instead trying to live the inherited ideals of the previous decade. The Watkins Glen Rock festival promised to be the Woodstock of the 1970s; I was one of the 600,000 people who flocked there. Not only did Joni Mitchell not write a song about us being stardust, the Grateful Dead noodled around endlessly and pointlessly. When the Allman Brothers took the stage, it was like Independence Day for every yahoo with a Confederate flag. I hated every minute of it. I did see a lot of exposed breasts and colorfully painted vans, but everyone seemed kind of shabby and clueless, white trash in hippie costume. I woke up one morning with my head tucked under the arm of a smelly and unfamiliar girl, my own hair matted and filled with pebbles. Epiphany eluded me.

Wandering around with a Mamiya hanging from my neck provided a temporary anchor for my aimlessness and gave me something to do with my hands. Although I identified myself as a photographer I was not consciously trying to make art. I simply photographed who or what was in front of me and that was almost always my friends. My photographs of friends were not metaphoric or cultural statements but modest acknowledgements that we had found each other in the cultural desert of Medford, we who were diverse in our bewilderments and united in our alienation.

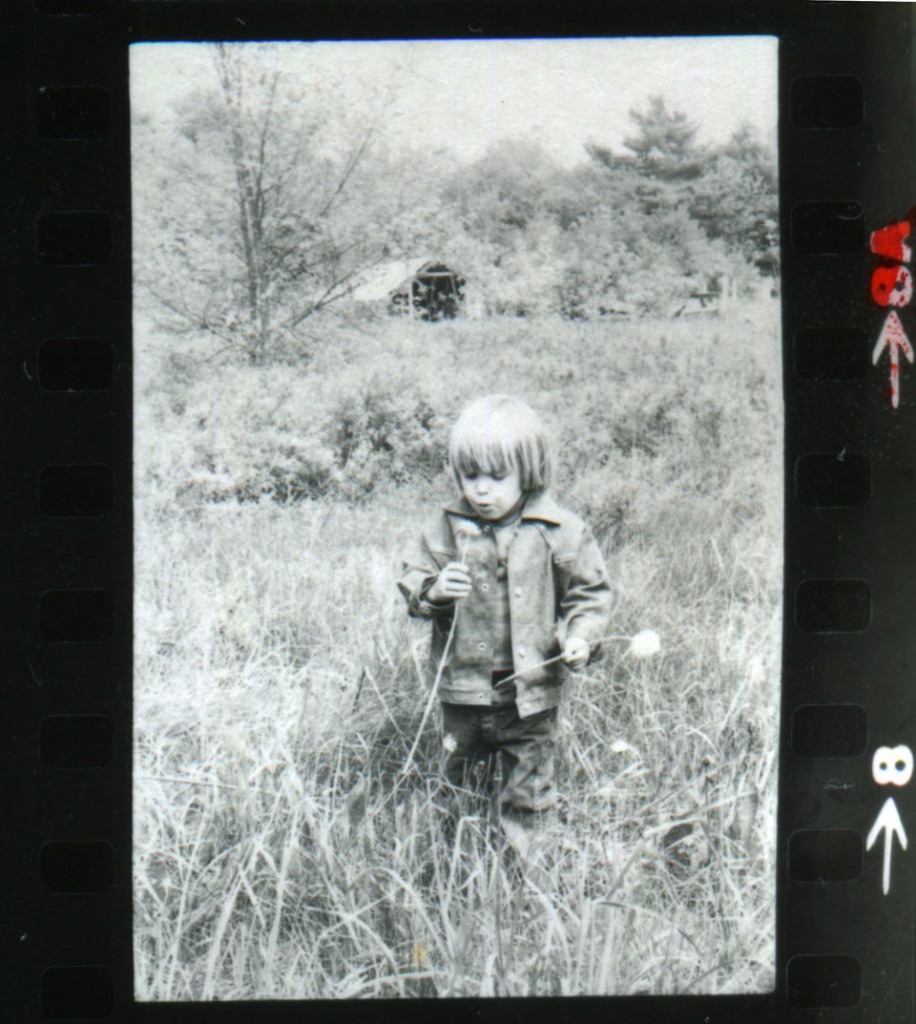

Unless I was viewing a landscape or organizing random objects into a still life, I never considered composition or perspective in any deliberate way. My first ‘artistic’ photograph was of my toddler cousin Terry, blowing dandelions in a field of tall grass. He was dressed head to toe in denim, his blond hair cut in a manner as to suggest a mini Brian Jones. All my aunts and uncles went nuts for this picture; I had somehow bridged the divide between trickle-down hippie esthetics and working class kitsch.

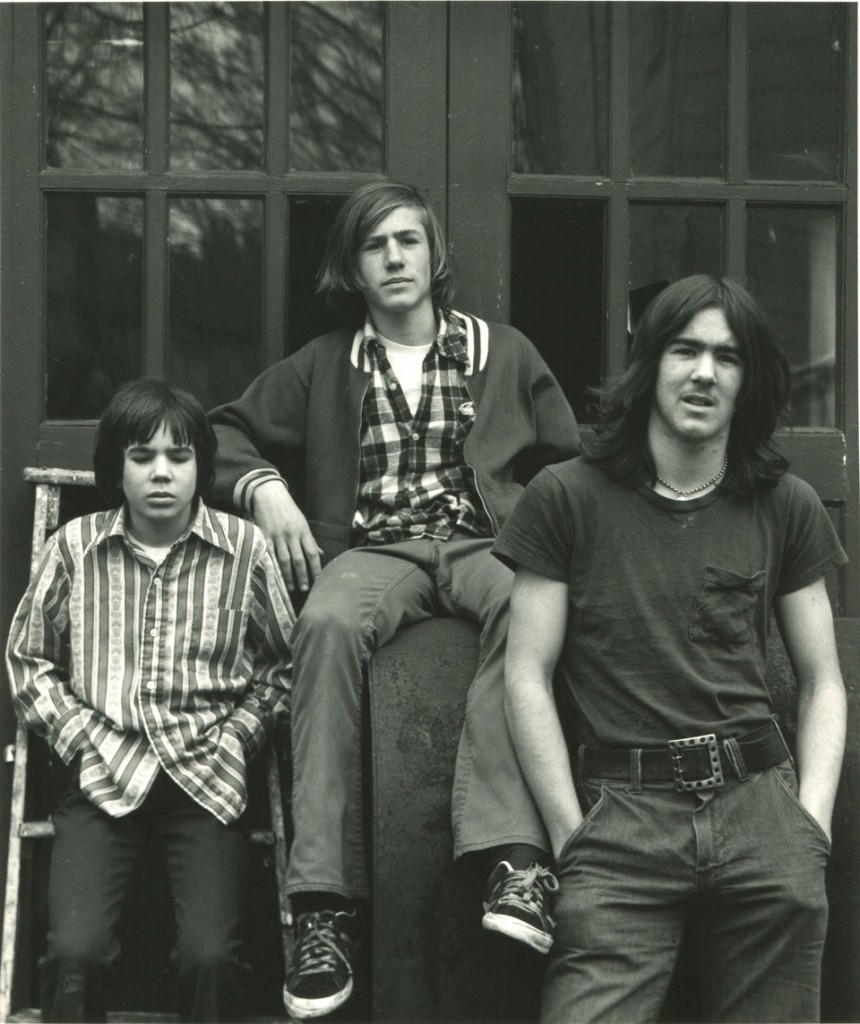

After high school I worked multiple bad jobs to save cash for a West Coast sojourn, after which I began attending the New England School of Photography where I was introduced to the 4×5 view camera. I loved every aspect of its clunky processes. Once under the dark cloth, I practically fondled the brass fittings, the snaky cable release and the accordion bellows. As expected, I made pale imitations of Edward Weston and Ansel Adams. Otherwise I mounted the camera on its hefty tripod and pointed it in the direction of friends and family.

My three brothers and I were, by this point fatherless. I was insecure about what kind of version of manhood I was offering in my father’s place. Just a few nights before this picture was taken I had a violent confrontation with local ruffians who climbed upon our garage roof almost nightly to smoke and drink and tear off the shingles. My mom was desperate. The confrontation ended with me seeking the protection of our basement while the ruffians chanted threats and beat on the door. My brothers were rougher than me, tougher too and not too impressed with my macho credentials. As I assembled them against our garage, I think I took notice of their shaggy beauty for the first time, saw the volatile mix of defensiveness, charm, bravado and resignation settle in their gestures of self-presentation.

To release the camera’s shutter is an acknowledgment that a moment is significant. Or, sometimes it is in the hope that we might confer importance and redeem the moment from the quotidian flow. In that sense, to photograph is a kind of paradoxical prayer, a gesture toward sanctity of the everyday that requires a temporary severing of that connection.

Somehow, after ducking beneath the dark cloth to focus the upside down and backwards image, I began to sense a gap between my subjects and me. In part it was the formal distancing required to make a thoughtful composition. But more keenly, I observed my own observational remoteness. I was stepping outside the myopic bubble of what James Baldwin calls ‘the adolescent dark’.

The stink of old fixer drifts into my nostrils as I squint through the magnifier to examine 40-year-old contact sheets. Red ink marks the frames I thought worthy of printing. I flip open the lid of a small yellow cardboard container and spread the still vivid Kodachrome slides across the light box. The blue skies of 1974 seep into my eyes like tears in reverse. Its such cliché that all photographs are time capsules, but when its your past, a past that only is accessed through misshapen memories, bits of dialog and doubts about whether certain things actually occurred, photographs can provide specificity, material clues to help prevent reverie from devolving into pablum.

Our tribe, our social experiment, our minor rebellion, lasted half a decade before acquiescing to jobs, college and mental illness. Kenny was my best friend, he cherished his blue-lensed glasses and studied geology, Barbara petite and tough, had the most passionate sense of social injustice, Michael, who ran away from an abusive home at 15 did not believe in brushing teeth and instead ate a lot of apples to keep his mouth fresh. Anita was horse crazy and worked at the local stable, leading trail rides and shoveling manure with glee. Charlie had the unfortunate luck to be a jock in our pacifist culture, he compensated by always chopping wood, building fires, carving peace pipes, and hoisting all of our backpacks onto trees at night.

And then there was Eddie, beautiful Eduardo Rojas, his Cuban hair thick as rope. As supporters of Castro and the Revolution, his elegant parents were forced to leave Havana nonetheless. This haunted them with a palpable melancholy that trailed behind them as they shuffled the hallways of their house like aristocratic refugees. Yet they were so kind to their son and his strange friends huddling in his bedroom listening intently to Hendrix. Eddie did not escape, at least not in any enviable way as schizophrenia pulled him inexorably toward a paranoid stasis in his early 20s. I don’t know if he remembers any of this, so these wisps and shards are offered in his honor.

Eddie was the most eccentric among us. In the face of violent mockery he bravely wore his pink tuxedo throughout his entire junior year. He inventively mangled Spanish and English to create a kind of meta-language that infused our world with nonsense and wonder. Within minutes he could play any instrument he picked up. His minor chord improvisations provided a constant soundtrack to our hazy meanderings. Through woods and over sand dunes, we followed him like a messianic troubadour, his pink tails flapping in the breeze as he led us on with clarinet, bagpipes, accordion or double-necked guitar, toward our utopia that most certainly awaited just beyond that ridge.

This essay originally appeared in Dear Dave, #14, Summer 2013.