Book Report #4

This is the fourth installment of a regular series on photobooks. Books discussed this time are Women’s Mobile Museum, (Philadelphia Photo Arts Center), Somewhere Along the Line by Joshua Dudley Greer (Kehrer Verlag), and Dhaka by Scott Benedict (Self-published).

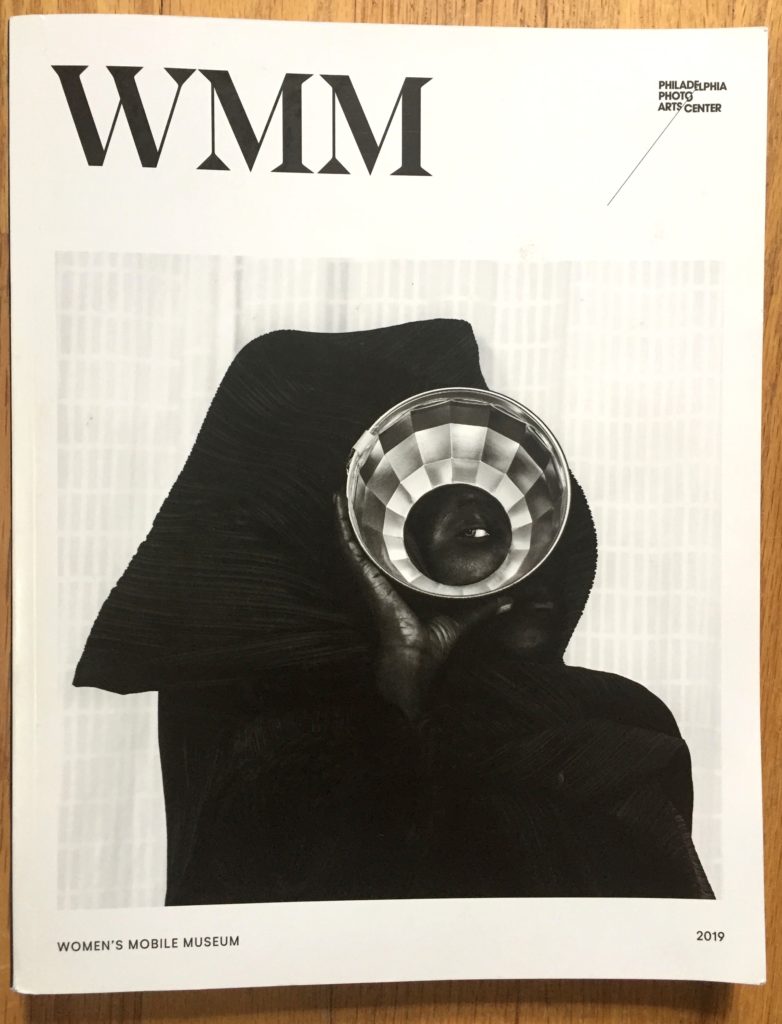

THE WOMEN’S MOBILE MUSEUM

The Women’s Mobile Museum (WMM) catalog is a document of “a collaboration between the Philadelphia Photo Arts Center (PPAC), the South African visual activist / photographer Zanele Muholi, and ten Philadelphia artists who identify as women and femmes.”

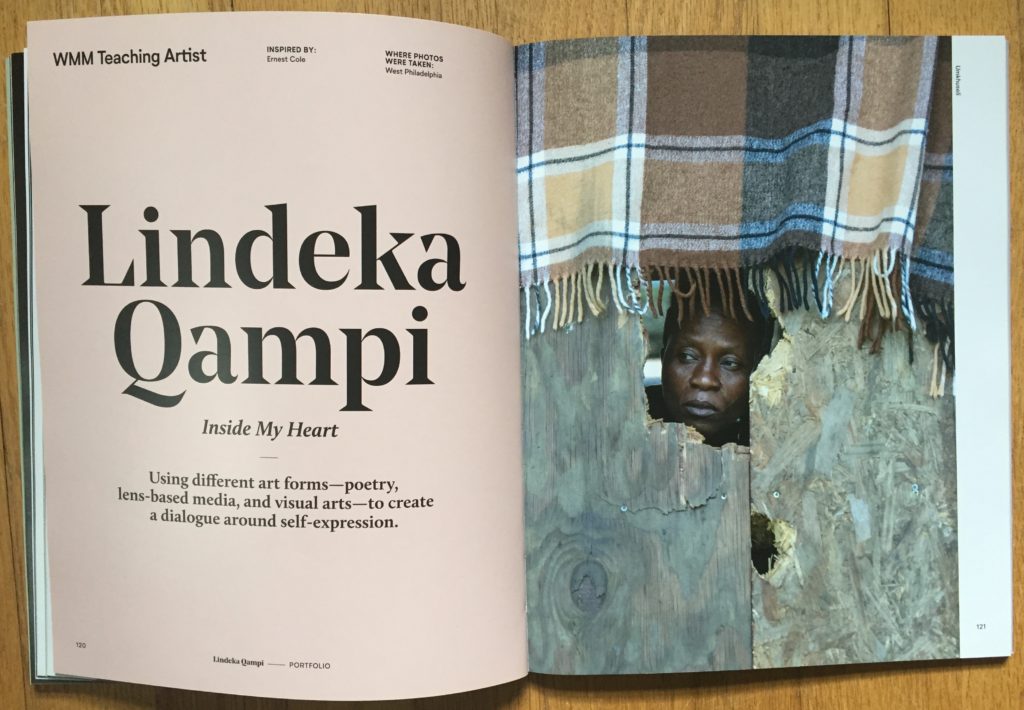

Everything about this project is instructive and challenging, from how participants were recruited, to the photographs and texts that were created during the workshop. With the goal of including people who “did not feel welcome in arts institutions nor have had the financial resources to engage with photography before,” the PPAC created a simple application in which women were “asked to describe themselves and why they were interested in the program.” 59 applicants were interviewed, of which, 11 were selected. Zanele Muholi, assisted by curator Renee Mussai and artist Lindeka Qampi, ran a six-week workshop for which the participants wrote, made photographs and participated in weekly critiques. Community exhibition sites were selected to show the works produced in the workshop. While in Philadelphia, Muholi not only led the workshop, she also continued to produce her series of self-portraits that have garnered so much popular and critical attention over the last few years.

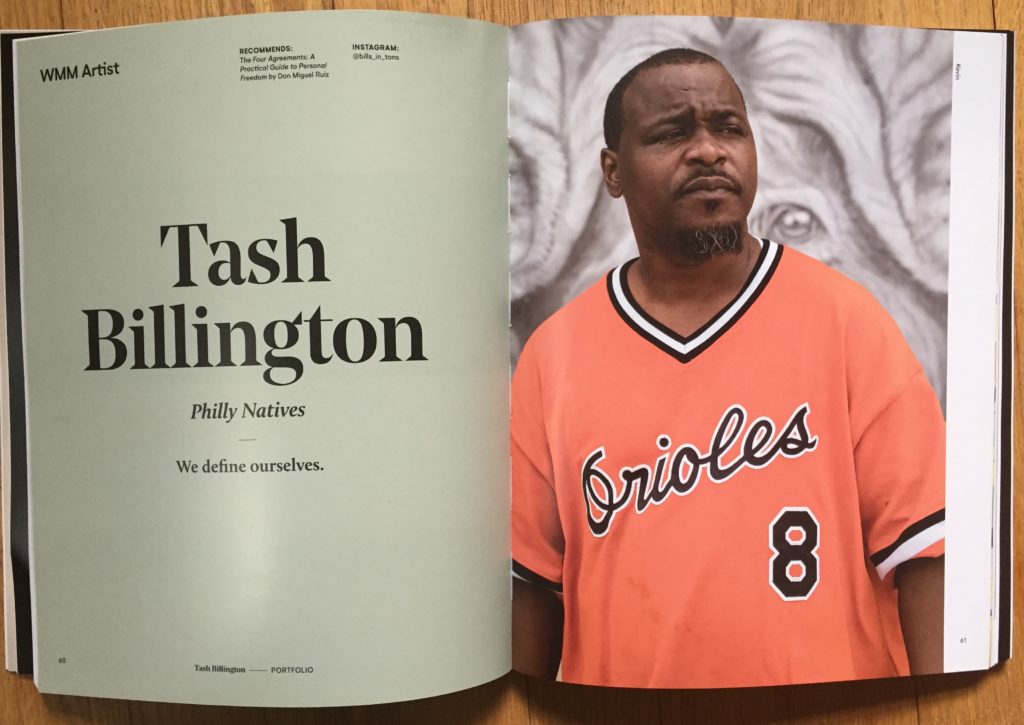

Women’s Mobile Museum artists include Andrea Walls, afaq, Iris Maldonado, Tash Billington, Shana-Adina Roberts, Davelle Barnes, Lindeka Qampi, Shasta Bady, Carrie-Anne Shimoborski, Muffy Ashley Torres, and Danielle Morris. Tash Billington makes portraits of Philly natives, she states that her work “rejects the outsider’s gaze,” and that the work seeks to “acknowledge the beauty and resilience often overlooked in the people of this city.” Shana-Adina Roberts also makes portraits, although her images are more atmospheric and suggestive. Her pages also include her bracing poetry. afaq works with language and image as well, to explore self-portraiture, she states: “I battle with religion, culture, blackness, love, gender, nationality, and what it means to be seen as other in a world of everyone else.” Davelle Barnes’ work is grounded in her experience in the military serving while the idiotic ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’ policy was in place.

The Women’ Mobile Museum catalog, rich with images and texts, including a great conversation between Muholi and Mussai, is not only a gathering of the many extraordinary photographs made in the workshop, but it also presents a vital model for inclusivity and visual activism. Many arts organizations pay lip service to inclusion and diversifying their audience. With this project, the Philadelphia Photo Arts Center demonstrates how it’s done.

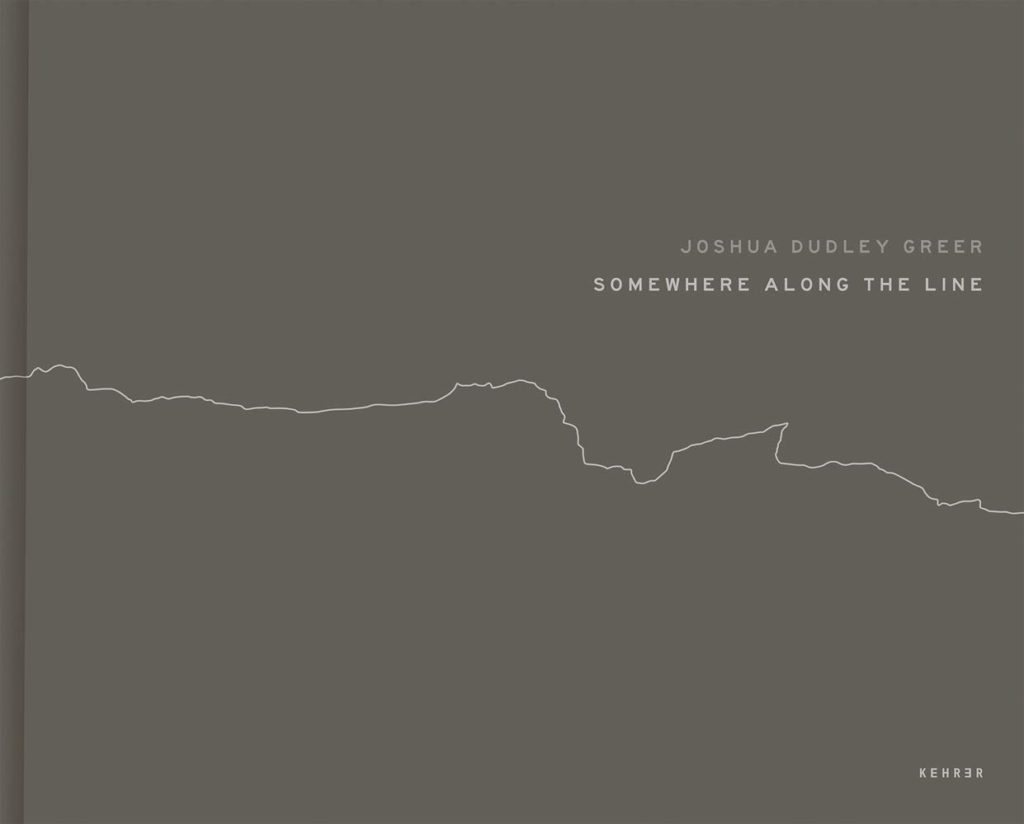

Joshua Dudley Greer is a photographer based in Atlanta whose work has appeared in many exhibitions and magazines, he also teaches at Georgia State University. His book of photographs, Somewhere Along the Line, with texts by Tim Davis and Ginger Strand, was recently published by Kehrer Verlag / Berlin. The images were made between 2011 and 2017 along the super highway network weaving across the United States. Working with a large-format camera, Greer has created and assembled a powerful and nuanced portrait of the American landscape. From Timothy O’Sullivan, to Robert Frank, Greer’s images refer to, echo, and extend, the rich photographic tradition of the road trip that is so much a part of American history and ethos.

In addition to the conceptual / procedural structure of following the highways to make them, the photographs are held together by Greer’s strategy of capturing images that embody both the specificity of place and the dreadful feeling that these are pictures of everywhere and nowhere simultaneously. The book opens with a close-up of the ubiquitous green directional signage that arch over interstates. Draped in black fabric, the signs are transformed into inscrutable funereal sculptures, announcing themselves dramatically but providing no direction, signifying nothing perhaps but a bleak end. The following photograph places us somewhere in Arizona, the arid reddish-brown landscape extending, seemingly, infinitely. In the foreground, on a paved cul-de-sac, two dogs act as sentinels, staring into the distance. I thought about many images, including Lee Friedlander’s ‘Albuquerque, 1972’ in which a lone dog, like a canine Waiting for Godot, sits on a street corner contemplating nothingness.

Homeless encampments under highway overpasses, a sea of motorcycle riders parked outside the Pentagon, a gutted Jetta rests by the side of the road in North Carolina like an unburied corpse, a massive sink hole swallows the road in front of a lonely strip mall in West Virginia; Greer’s book contains many powerful photographs that condense the essence of place and the general angst of the current American moment. He has made a photograph in my beloved Baltimore which shows boarded up homes in close proximity with those which are lovingly tended, an image which perfectly captures the city’s spirit and challenge. Although sometimes grim, the photographs in this book are beautifully constructed, and often have an undertow of dark humor as in the hand-painted billboard on Interstate 70 in Kansas that proclaims, “I Need a Kidney.” Greer’s book is beautifully produced and vital document of our time.

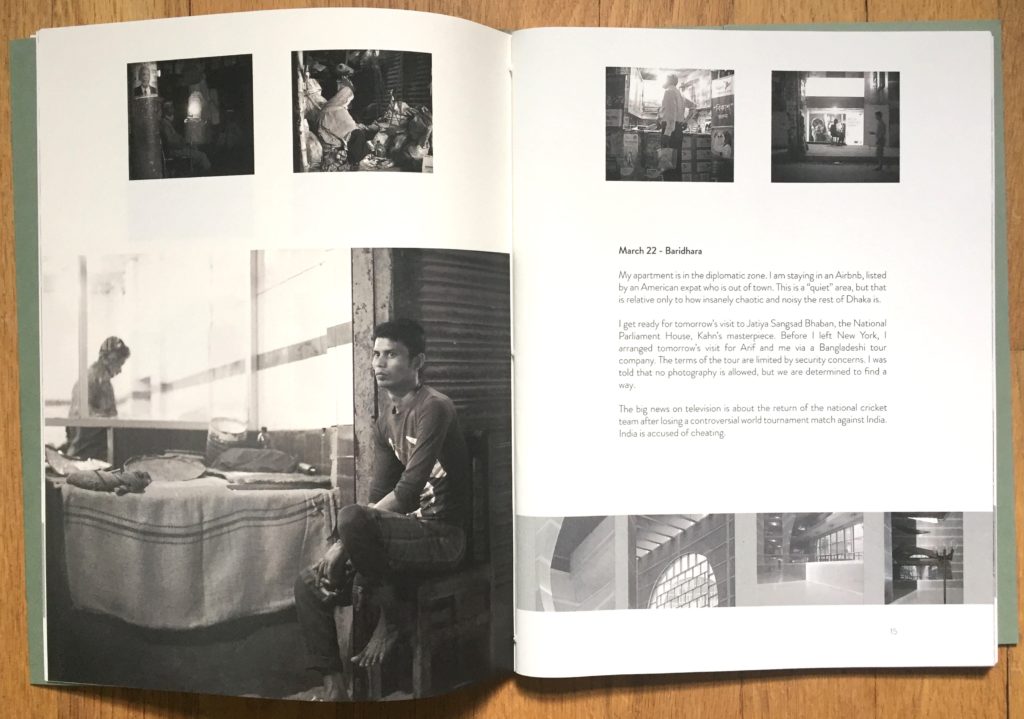

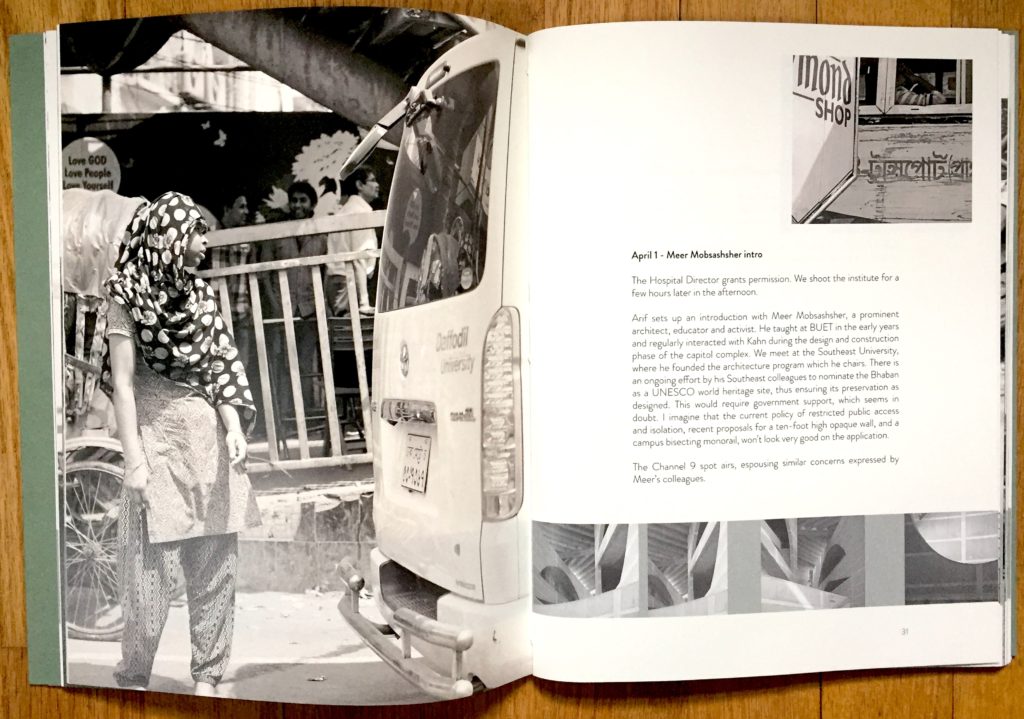

Scott Benedict, a photographer based in Hudson, New York, is also a trained and practicing architect. Not surprisingly then, his work as an image-maker and writer has concerned itself with architecture, its history, its relation to landscape and social environments. His self-published book, Dhaka (released in a limited edition of 300), is an elegant document, in words and pictures, of his travels to Dhaka, Bangladesh, to photograph Louis Kahn’s House of Parliament, considered by many architectural historians to be Kahn’s masterpiece.

Official concerns with security and protocol resulted in Benedict’s photographic agenda being met with bureaucratic resistance, to put it mildly, on the part of the Bangladeshi government. Despite Benedict’s inability to gain permission to photograph in the House of Parliament, he decided to travel to Dhaka nonetheless, for what he calls “a multitude of practical and delusional reasons.” The lively design of the book leads the reader through Benedict’s travails, the obstructions he faced, the streets he walked, the Bengali citizens he photographed. It is a fascinating tale of esthetic obsession and thwarted desire. Benedict is able to convey a faceted sense of place that encompasses the social landscape of Dhaka, the texture of the city, and his own internal struggles as he negotiates the Bangladeshi bureaucracy. His book then, by necessity, is a journal of frustration, a diary of unmet expectations. He faces failure with equanimity and understated humor. It is an epic misadventure; the paradox is that it produced something that is perhaps more instructive, more fascinating for a wider audience, than his original intentions.