God’s Documentarian

All artists play God; they are lords of their creations. Some play God with more enthusiasm and fervor than others. People who worked with film director Stanley Kubrick witnessed (or survived) his obsessive attention to detail, his relentless push to satisfy his perfectionist’s eye. The actor Ryan O’Neil, who starred in Barry Lyndon, described Kubrick as having power over climatic conditions, as if he were able to part clouds and call down strafing sunbeams to illuminate a scene. After even a casual survey of Kubrick’s cinematic worlds, from the metaphysical 2001: A Space Odyssey to the dystopian A Clockwork Orange to the period drama Barry Lyndon, it would be difficult to refute Kubrick’s mastery.

Regardless of your interest in Ansel Adams, whether you think his work ‘classic’ or anachronistic, pure or fallacious, he remains the most godlike in the history of photography. His images of unblemished primeval landscapes combined with a kind of esthetic absolutism that practically defined what it meant to be an American photographer in mid-20th century. With his white beard, his rigor and benevolent manner, he came down from the mountain and presented the Zone System as a guiding principle for serious photographers. While many of us have rebelled, become agnostic or followers of other idols, the masses still revere him.

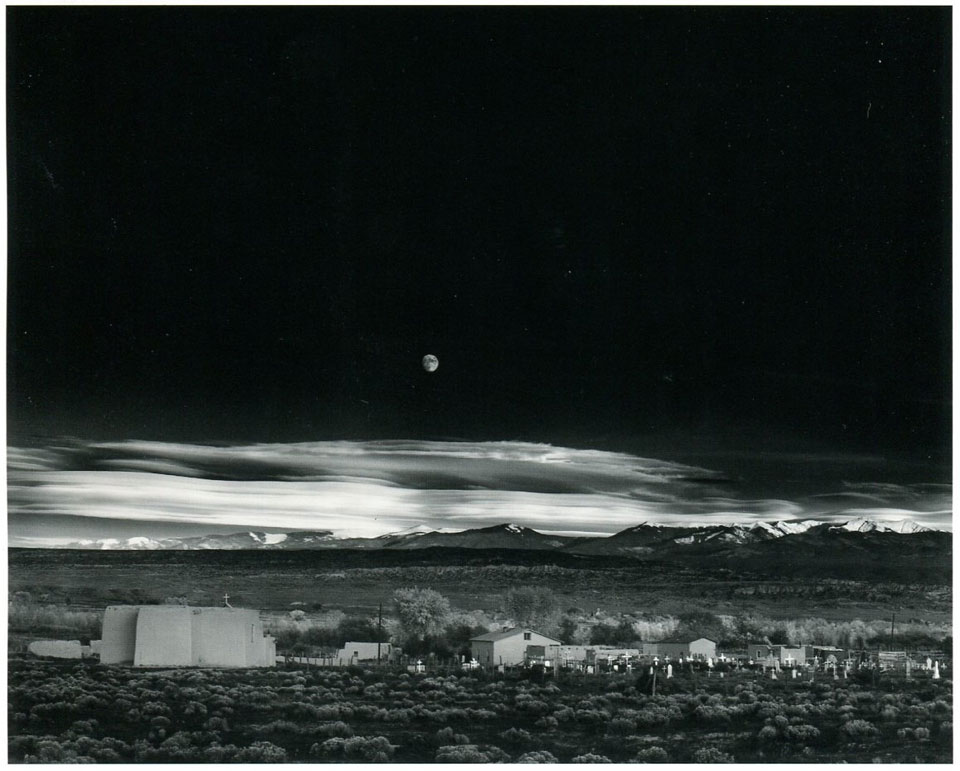

Let us revisit one of his creations and see if we can resist bowing before his greatness. Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico from 1941 is Adam’s most reproduced photograph. There are images that are graphically more dramatic such as Moon and Half Dome from 1960 or the exaggeration to near abstraction of Unicorn Peak and Thunderclouds from 1967 but these were made later in his career when he was perhaps a bit too emphatic in his printing. Despite its apparent stillness Moonrise, Hernandez was made in a hurry. Driving south on the way to Santa Fe, his eight-year-old son Michael and his friend Cedric Wright in the car with him, Ansel looked to the east and saw the moon rising over the Sangre de Cristo Mountains complemented by a final glimmer of sunlight illuminating the adobe village of Hernandez.

After a 60 second flurry of activity to set up the tripod and camera, one exposure was made, and by the time he could flip the film holder to make a second exposure, the foreground had fallen into a shadowed twilight. In his haste, Adams could not locate his light meter, so he set the aperture and shutter speed by calculating the moon’s luminescence in relation to the rest of the scene. The glow of the moon was not simply a romantic trope but a measureable light source. Adams sold his first print of Moonrise, Hernandez for $25.00, in recent years a vintage print from 1941 was sold at auction for $600,000.00, but that is another story.

I can think of few images in the history of the medium that so immediately and grandly displays the connection between the individual and the cosmos with such an elegant economy of means. The metaphysical scale of this picture is like an inverted pyramid. At the bottom, or pointed end, we find the individual grave marked simply by a wooden cross, beneath which rest human remains. Behind the graveyard a humble village, an adobe church anchoring the north end. The village is nestled on the east side by a close-knitted grove of trees peeking above the rooftops. Beyond the trees, open high desert creeps toward the snowy peaks of the Sangre de Cristo, behind which alto-stratus clouds stretch across the entire panorama like icy white drapery.

Floating above the terrestrial scene is a waxing moon, its craters and seas finely etched into its silvery face. Our satellite is a lifeless rock ensnared in earth’s orbit; it is our stillborn offspring destined never to thrive but to function as a malleable symbol of night and myth. The top half of the photograph embodies the sublime threat of the infinite. A luminous darkness presses against the earth’s atmosphere reminding us of our isolation, that the space above our oxygenated cocoon is largely empty and beyond measure. This is a photograph of profound beauty and loneliness and it reminds me of something Kubrick said:

“The most terrifying fact about the universe is not that it is hostile but that it is indifferent, but if we can come to terms with this indifference, then our existence as a species can have genuine meaning. However vast the darkness, we must supply our own light.”

If we accept film theorist Andre Bazin’s notion that the material world is God manifest, then all of photography is a record of God, and Ansel Adams is God’s most worshipful documentarian. In the Greek pantheistic model, Ansel would be a demigod of silver and light, at whose altar we humbly offer our own photographs hereafter. If instead we are inclined to agree with Kubrick, than Adams is one of our greatest suppliers of light and we should be thankful that he faced universal indifference to create such luminous objects.