28 Notes for Roy DeCarava

1. I am not nostalgic but I want to visit the world of your photographs.

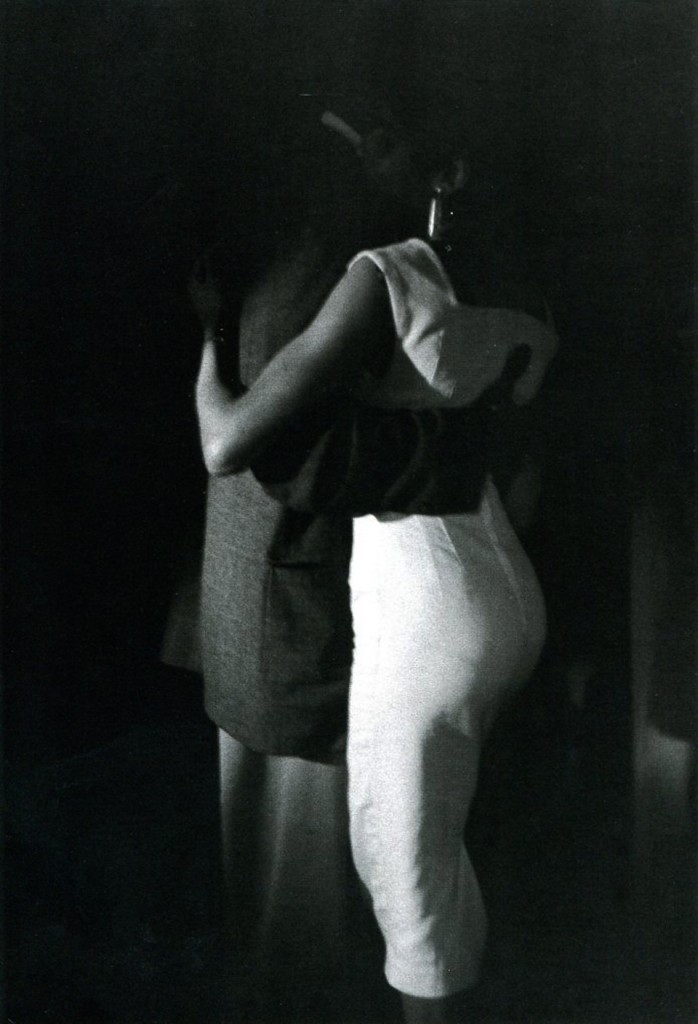

2. One of the first paintings that ever captured me was Renoir’s man dancing with a woman. In my memory the couple swirl in a vortex of blue and pink. While the brim of the man’s hat hid his eyes, I knew they were filled with ardor. It was the first time that I understood that art could suggest something without showing it. Your photograph of a couple dancing in 1956 hides even more. They embrace at the edge of darkness, swaying in that liminal space. Will they twirl into the luminescence or slink into shadow? Their heads bow toward each other in mutual adoration. The way they fit together makes me ache. I want to pull her warmth into my gravitational influence. I need her hand planted in the middle of my back to anchor me from an erratic orbit.

3. You said that a lousy camera could make a beautiful photograph – that beauty is in the person taking the photograph.

4. You describe the territory between the entwined and the entangled.

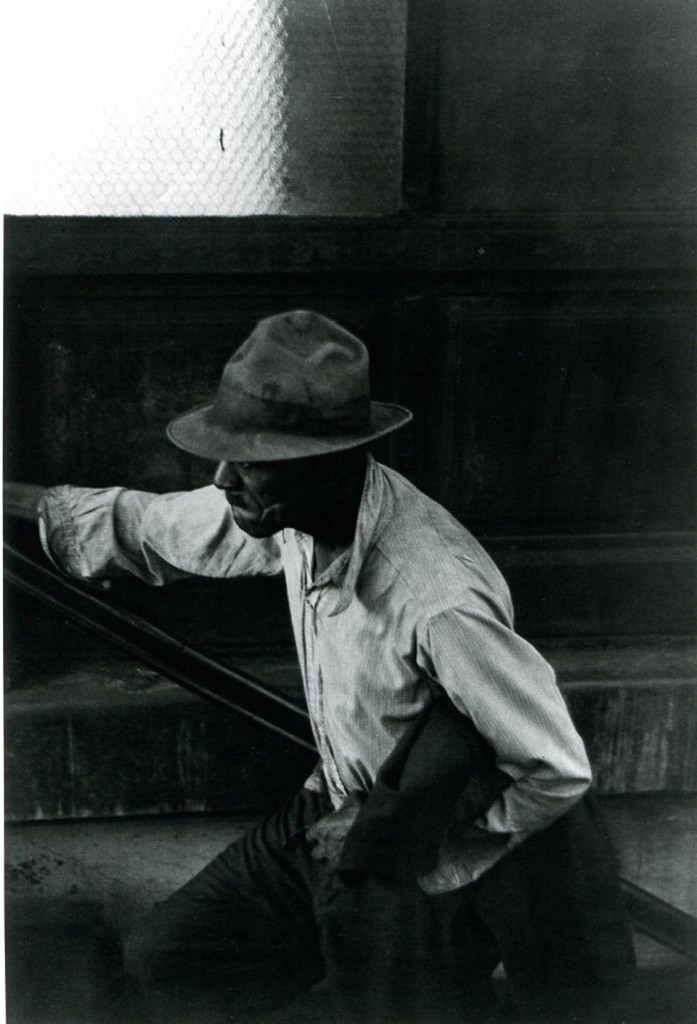

5. A man climbs the subway stairs in New York, 1952. He reminds me of the trudging industrial slaves in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. How long did you wait for this dark angel to process from the bowels of the city? His embattled fedora, sweat-stained and dented, hovers over his head like smudged halo. He is the proletarian’s silent companion, witness to drudgery and quiet rage. He arrives early, before the sun’s promise, so that he can wrap his arm around workers’ shoulders to help them rise and face what you call ‘the crush of every morning’.

6. Pliny and others have suggested that the history of painting began with longing. The first artist drew the outlines of her lover’s shadow before he set off on a dangerous adventure. His shadow became a ghost, haunting her future without him with the half-life created by memory. This is the photographer’s condition.

7. You were born an artist in Harlem. Almost as soon as you could crawl, you spent hours making sidewalk drawings in chalk – your first exhibitions.

8. Shirley looking down the stairwell, New York, 1952. In her sweet summer dress, Shirley is enveloped in dim filtered light. She presses herself against the railing, raising a soft mound below her belly. I hope something or someone fine is ascending as she waits on the landing, but her expression suggests otherwise.

9. The standard definition of photography is ‘writing with light’. This seems inadequate to describe your process. You quietly redefined the medium to carve with darkness, to inscribe with night, to sing with shadow.

10. I would like to have watched you in the darkroom. Did you dreamily move from enlarger to developing tray or did you strut decisively under the crimson safe light? Did you hum, whistle or sing Duke Ellington or did you cultivate a monastic silence?

11. Immersed in the developing bath the photographic paper begins a shiny and resistant white, after a few moments, wisps of smoke-like patterns emerge. Within a minute a souvenir of the world floats below you like a hallucination. You know it is optics, physics and chemistry, but every time it still seems like magic, the alchemy of sight and memory.

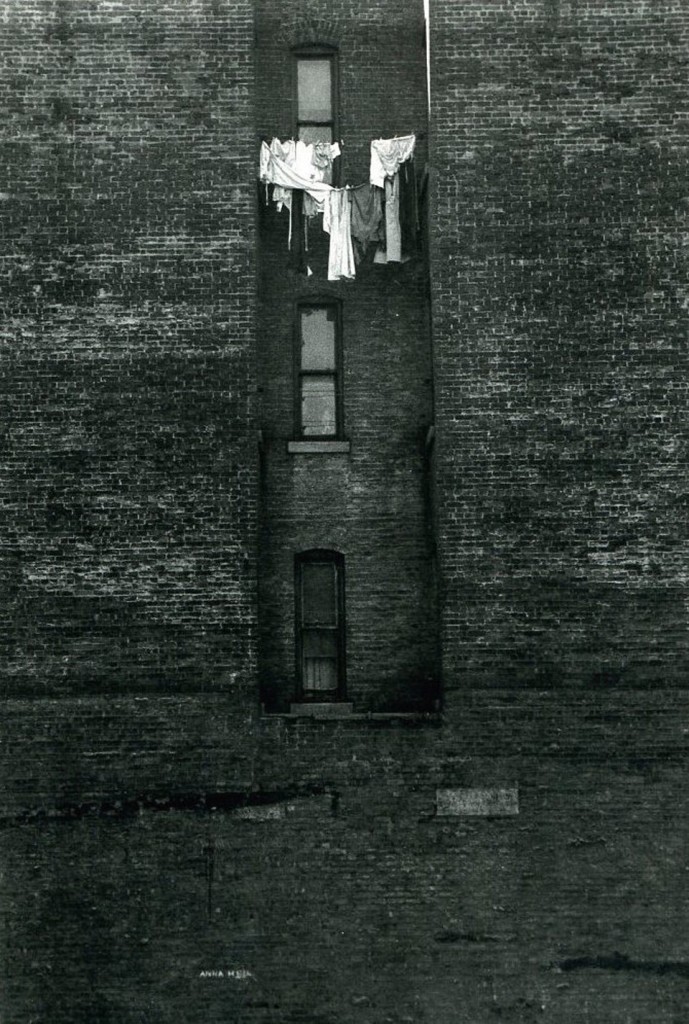

12. Child in the window, clothesline, New York, 1950. You have composed your photograph like an abstract expressionist painting: chunky rectangles of textured dark tonalities with a slice of white piercing the top of the frame like a taunt from the infinite. Without the title I might have missed the child behind the middle window. Between two upturned hands she cradles her head like a pillowed prayer. The floating clothes are threadbare clouds.

13. You said that if you bring light into a dark place it changes, and maybe it is the darkness that one falls in love with.

14. Your politics are in your tonalities.

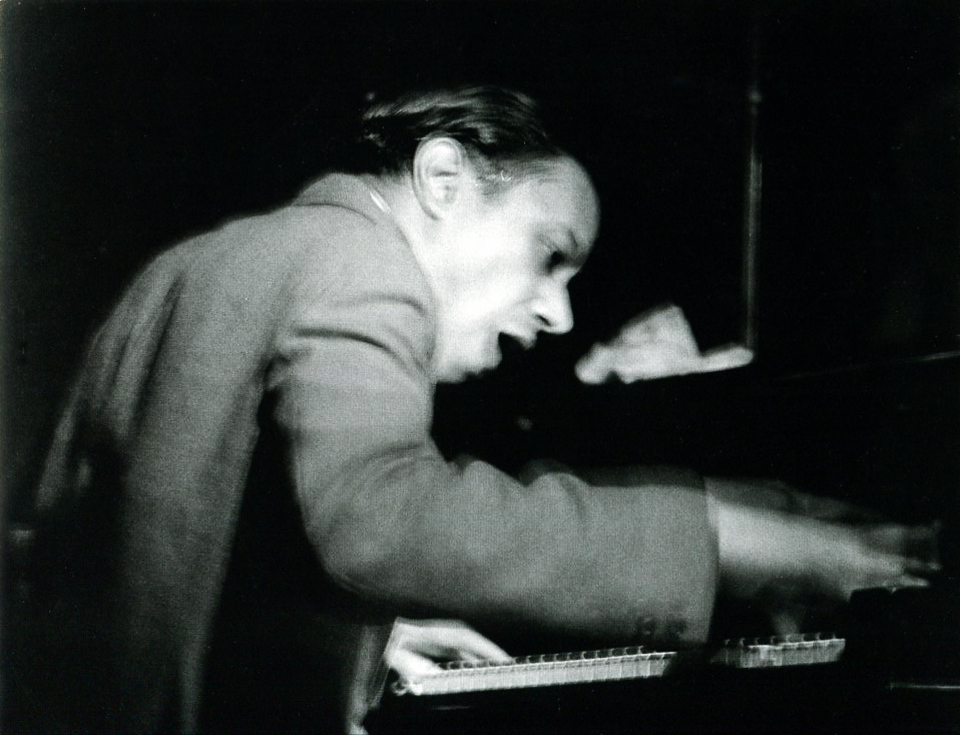

15. I hate my ignorance and that makes me hungry. I knew nothing about jazz so I went to jazz clubs often without knowing who was playing. One night I walked into the Village Vanguard and discovered Horace Silver hunched over the keyboard sweating profusely. Between chords, a white handkerchief would fly out of his pocket like a frantic banner. His long hair was slicked back, cascading over his short neck which was swallowed by his hunching shoulders. When he played the first notes to Song for my Father I was reminded how much black music is stolen by white musicians. Later I saw your photograph of Horace. In granular dimness his face hovers and stares intensely at the ivories as if to tease out their secrets. Horace’s crumpled handkerchief a soft blur just beyond his gaping mouth.

16. You printed photographs in your own language of tonalities. While other photographers printed brightly with exaggerated contrast, you found a smoky and granular aesthetic that could tease out a multitude of accents and attitudes among an infinite variation of grays and blacks.

17. Your late night diner still life features salt and pepper shakers, two snuggling bottles, two bowls and an empty glass stacked upon one another, a soiled napkin and a woman’s jacket draped over an empty chair. The background is as black as a night without stars, a stage set after the actors have gone home. How would Georgio Morandi, arranger of elegantly paleness, react to the velvety depths of your photograph?

18. Camera Obscura – a dark chamber that allows light to pass through its calculating aperture allowing us to see contemplatively.

19. Your images are not content with a simplistic binary of light and dark. Instead we feel a pull, a force, a quiet volatility, an incessant tug between luminescence and shadow.

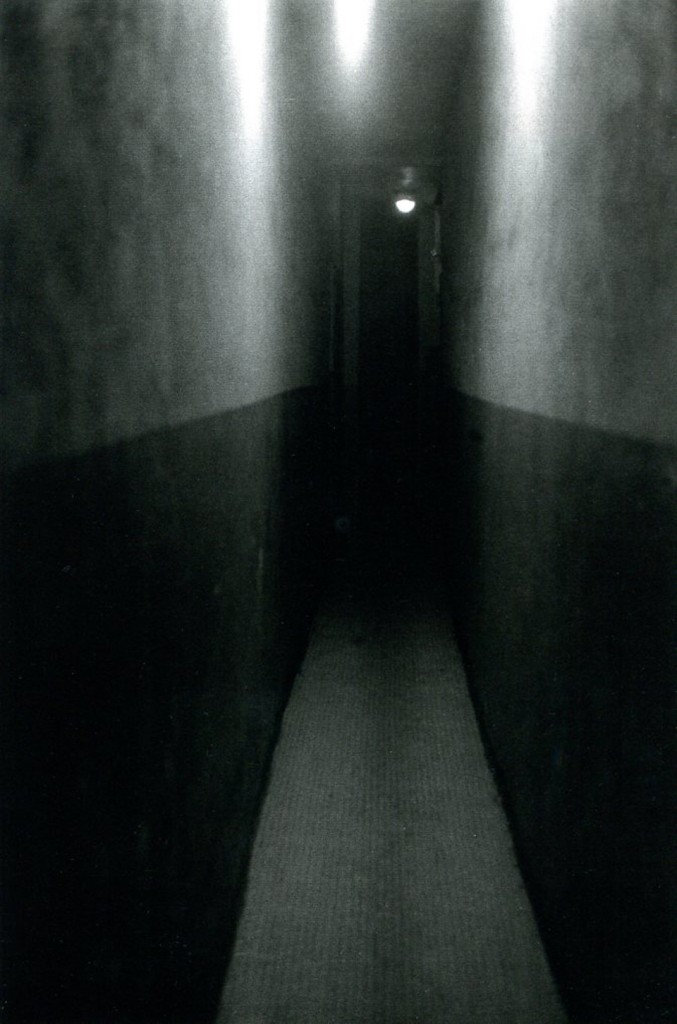

20. That hallway in 1953. A child might never get over the fright that passage would instigate; it is a place where innocence ends.

21. Two boys gesture toward the rubble. They point at nothingness. Behind them looms a featureless wall of unrelenting brick. A large letter ‘C’ is scrawled on concrete. Ha, ha, a semiotic game. See this emptiness? The only window here is the implied photographic window, through which generations have now peered. We are on the outside and in the future. We can turn away, at a time of our choosing, toward the modest pleasures of our present moment.

22. You employed rubbled lots like ravaged proscenia. It’s Waiting for Godot in Harlem. Your characters are refugees in their own country.

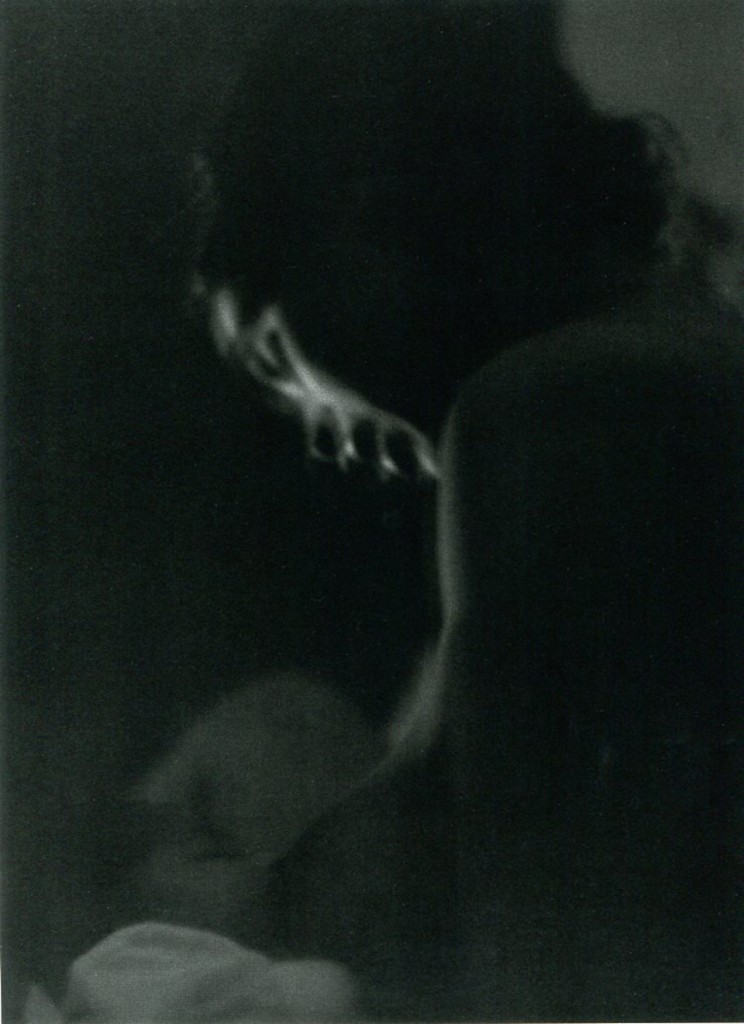

23. Night Feeding, New York, 1973. This is the holiest image made in the history of art since Bellini. In the twilight of a dim star your wife Sherry offers her breast to your daughter Susan. Deep in the night you awaken bleary-eyed when you sense, even in your dreams, the aura emanating from your loved ones, as if they are generating their own light from within. You get out of bed and reach for your Nikon, open the aperture and shutter believing that this miracle of the ordinary will pass through your lens onto the skin of film.

24. Darkness is not a wall or an end. It is a universe of undertones, a place of infinite subtleties. We must adjust our perceptions and expectations if we are to benefit from its liveliness.

25. You did not have to go looking for Langston, Langston found you. He fell into your photographic world like a happy drunk. You gave him 500 prints to take home, he lived with them, conversed with them, inhabited them. Your photographs animated him and he came back some months later with The Sweet Flypaper of Life, a joyful antidote to the patronizing clichés of social documentary.

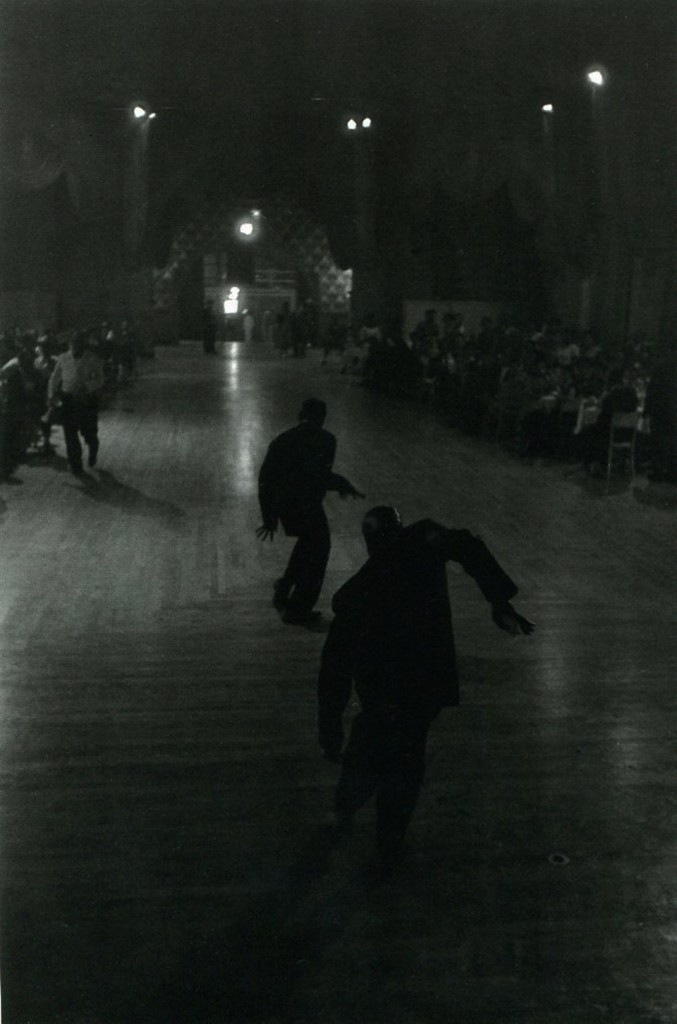

26. One of your most famous and beloved images is Dancers, New York, 1956. It shows two contorted bodies silhouetted by the dull shine of a wooden dance floor. Bracketed by a gauntlet of people sitting down for dinner, the dancers express their presences like exaggerated signs. Despite its animated humor, you felt deep ambivalence about your photograph because it implied a history of the shuffling negro, a caricature of survival, and the painful contradictions of the black body in relation to the white gaze. Yet you loved the image because it captured represented a wily spirit, an ironic nod to the creativity of black folk in the face of oppression.

27. You loved your picture of Milt Jackson, master of the vibraphone; you said it described the movement from ritual to religion. It is a holy picture, Milt with his head raised, hands tenderly clasped and eyes gazing upon the infinite. You are the visual scribe of America’s most brilliant and courageous generation of musicians. Your image of Milt Jackson captures him not playing but listening, listening to the notes conjured by another, enraptured, suspended, attentive, astonished.

28. You said that art has the ability to speak many languages. You said that art gives us the benefit of someone else’s feeling and experience. You said that art is one of the most important things a human being can do. You said that all societies produce art and that art is essential to human communication. You said that you wanted to address the human condition. No one talks about the ‘human condition’ anymore, or if they do, they are accused of being sentimental or naïve. What fool would dare call you sentimental or naïve?