1440 Decisions to Look

Before Baudelaire redeemed him in The Painter of Modern Life, the image of the flaneur was that of a time-waster, an idler, a young man wandering the streets with no purpose. Describing the flaneur as “a passionate spectator” and “a kaleidoscope gifted with consciousness”, Baudelaire redefined the solitary urban observer as a rough connoisseur, imbibing the subtle pleasures of the city, its chance juxtapositions, its minor dramas. The flaneur became the model for the modern artist for whom the theater of the street would spark reverie and revelation.

Artists have always been drawn the city of course; until photography, it was almost always in the form of symbol, allegory or metaphor. Fra Carnavale’s The Ideal City from 1480 presents tightly arranged tableaux of historic architecture as a metaphor of good government, a stately balance of scale between state and citizen. Almost five hundred years later, George Grosz’s lurid Metropolis presents the Weimar-era city in pandemonium, streets claustrophobically inhabited with monstrous citizens indulging every kind of base desire. This image is as garishly exuberant as The Ideal City is soberly restrained and these two visions represented a stubborn binary of excess and moderation that have dominated the popular imagination for generations.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, photographers of the city, such as Eugene Atget, were themselves spectacles as they set up their clunky tripods and cameras for long exposures. There was no surreptitious angling to catch people unaware of the camera. Consequently Atget’s images tend to look like empty stage sets, formal yet haunted. When he did photograph people, they posed themselves self-consciously as might performers at rest. With the appearance of the 35mm format in the mid-1920’s, the photographer was unburdened from the cumbersome large-format camera and could assume the role of the flaneur strolling unnoticed among the people, camera tucked into one hand, finger on the shutter release, always ready to take an image in an instant.

The role of the street photographer was to prowl and furtively reproduce what Baudelaire called ‘the multiplicity of life and the flickering grace of all of it’s elements”. The major and minor epiphanies of the resulting improvisatory photograph can be discovered in the images of Henri Cartier Bresson, Brassai, Robert Frank, Roy DeCarava, Helen Levitt, Garry Winogrand, Lee Friedlander, Daido Mariyama, to name a few. Cartier Bresson coined the term ‘decisive moment’ to describe that point in time when the formal and narrative elements of a photograph come together in a perfect synthesis of form and content. Whether photographing in Paris or Beijing, Cartier-Bresson framed the world as a proscenium, its citizens as minor characters in an epically fragmented narrative. As if to follow that model, the history of photography is generally written as a collection of moments, disparate, dispersed, yet tightly edited and sequenced.

The history of 20th century photography is dominated by this practice that curator Kerry Brougher calls ‘social surveillance’. Street photography was so ubiquitous and synonymous with what it meant to be a modern photographer that by the mid 1970’s its habits and assumptions came under the critical eye of Susan Sontag who described “an armed version of the solitary walker reconnoitering, stalking, cruising the urban inferno, the voyeuristic stroller who discovers the city as a landscape of voluptuous extremes”. It is true that to photograph is to participate in an asymmetrical equation of power. To roam the streets and photograph strangers is to assume the privilege of sight over all other concerns and the activity begs ethical questions about privacy and aggression. Sontag’s critique was a factor in the decline of street photography as a legitimate practice and was a subtext in the birth of post-modernist practices. With the rise of photo artists such as Cindy Sherman and John Baldassari who utilized photography not as evidence of the existential confrontation between individuals on the street but rather ideas about representation and media, it appeared as if this rich but contested chapter in photographic history was coming to a close.

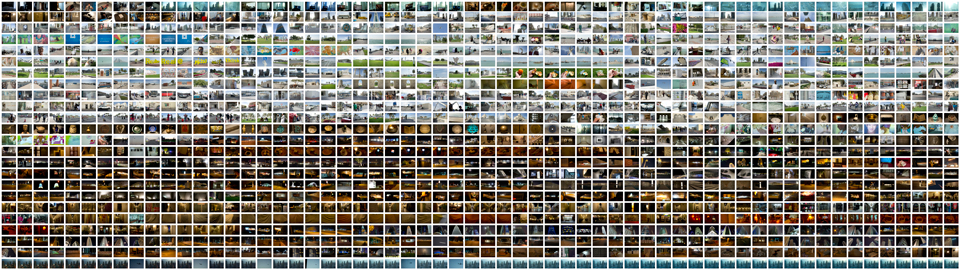

Roberto Lopardo has found a way to resuscitate and expand the idea of street photography in a way that implicitly acknowledges its problematic past without jettisoning the promise of the chance encounter. This is not as easy as it sounds. His monumental grids are indeed physically impressive yet refreshingly free of sweeping rhetoric or overwrought symbols about the state of the 21st century city. Because no single image is privileged over another, there is instead a cumulative affect; Lopardo’s large-scale photo works weave transitory moments into an immersive visual experience, in which tensions, contradictions and instants of fleeting beauty manifest themselves in the most humble and unprepossessing corners of the world. Lopardo provides a rigid structure to capture the disordered inventory of everyday life.

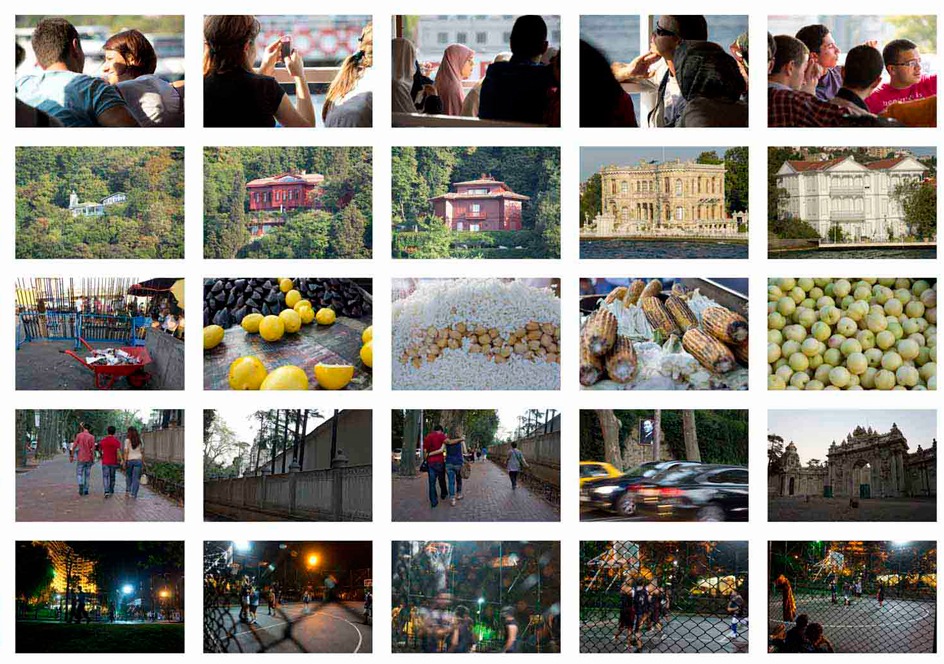

Considering that he is an American living and working in the Middle East, the titles in this series might suggest something fraught with political minefields; Mapping Kuwait, Mapping Jerusalem, Mapping Jeddah, etc. Lopardo confounds these expectations by creating documentary evidence of twenty-four hour walks through the various neighborhoods and districts that comprise the fabric of these varied cities. With a wristwatch alarm acting as a prompt, he moves intuitively, sometimes following a sound or moving toward an interesting architectural feature in the distance, taking a photograph once a minute. Over the course of the twenty-four hours he does not sleep, nor does he stop and linger on any one subject for very long. He will have a meal and occasionally hop in a taxi or bus to get to a different neighborhood, but the procedure he has set up for himself; one photograph per minute over the course of twenty four hours, proceeds inexorably toward the total of 1,140 frames. In this sense, Lopardo’s project has much in common with conceptual and performance art. He sets up a rigorous structure, a beginning point and end point; with strict limits put on the vagaries of personal subjectivity. In the process and in the presentation, no picture takes precedent over another; all are of equal value.

Art is most often discussed in relation to the viewer, but just as important is the experience of the artist. Lopardo’s wanderings around foreign cities are physical, emotional, esthetic, psychological and political challenges. Like a shark that has to keep moving, Lopardo is compelled to proceed into the unknown around the next corner, or down that darkened alley, or toward that minaret glowing dimly in the early morning light. He might find himself at the dwindling edges of the city where human habitation gives way to desert. He is sometimes seized with a solitary anguish on an empty street late at night, the litany of self-doubts interrupted by the signal to take yet another photograph. Darkness gives way to light, literally and figuratively, as Lopardo finds himself in the intense concentration of looking closely at the world for what it actually is, instead of what we imagine it to be.

There is a power dynamic in every decision to take a photograph, sometimes explicit sometimes subtle but it is always there. On the most fundamental level, to take a photograph is to confer importance on the moment, as if to proclaim, ‘this is worth saving’. Furthermore, the photographer is not a passive observer; he is recording his observations with a sophisticated tool. No matter the intentions of the photographer, whether benign or malicious, people observe the observer; he is a stranger met with hostile eyes glaring with the unspoken ‘What are you doing in my neighborhood?’ Lopardo’s performance, his explicit presence and unrelenting documentation of every minute are partly an acknowledgement of the fundamental aggression of photography. In this uneasy role we might think of Garry Winogrand.

This referential aspect of the work is also at play in the presentation of the Mappings, which are in effect, enormous light boxes, six meters in length. Anyone who has studied analog photography, has spent any time around a darkroom, developing and printing photographs will be intimately familiar with the light box, over which photographers hover, peeking through magnifying devices to examine their negatives or slides. For many photographers this was a deeply meditative process; quiet moments in determining which images best represent the subject and the photographer’s intention.

Lopardo’s Mappings offer simultaneity of images; we can follow a sequence, scan in a radial fashion making discontinuous associations or pensively examine individual images. This is an emphatic alternative to the manner in which most photographs are displayed discretely in window-like frames behind glass. The visual gravity of scale draws us in close revealing the exact sequence of every image over a twenty-four-hour period. Lopardo has not edited anything out, has not decided which is the ‘best’ photograph. One can literally trace his path in sixty-second intervals and imagine the pressure, the panic, and yes sometimes even the boredom of being prompted every minute to take a picture. In his monumental grids, we observe every decision to look.

And what do we see? In Mapping Kuwait, for example, we observe a television in a hotel room, twenty-one frames of Lopardo getting a haircut, water sprinklers keeping lawns green under the desert sun, bits of pop culture, random shrubbery, a hazy sea, big red doors numbered from 1 to 7, a man putting on a keffiyeh, lights hovering over a parking lot like some otherworldly vision from Stephen Spielberg, an omelet disappearing bite by bite, food stalls and malls, illustrations of political figures, empty playgrounds at night, construction sites and naked mannequins. It is Kuwait City yet it could be almost anywhere, photography as index and as enigma, paradoxically unique and quotidian. The city is not mapped with any apparent logic except for the moment-to-moment decisions of a photographer who is experiencing and hoping to capture the inexorable drip of the minutes passing. For Lopardo photography provides a temporary reprieve from the unassailable fact that time is a thief and that all moments dissolve like apparitions.

The photographer Paul Graham has stated that the power of photography is in the territory where documentary and artistic instincts coalesce. The instinctual yet structured territory that Lopardo is mapping is improvisational within a set of rules and situated between the material world and our projections of that world. These massive grids are not mere formal exercises, accumulations of rectangles representing abstract units of time. No matter how mundane, a photograph is always ‘this moment, this place’, and through the sheer visual weight gathered by this relentless accumulation of the quotidian, all of the implied questions rise up between the frames: Who is on the street and why? Where am I allowed to go? What is my connection to the world? Do I belong here? Is any one moment more important than another? Is everything significant or is nothing?

This essay originally appeared in Contemporary Practices: Visual Arts from the Middle East, Volume XIV