Zoe Leonard

Zoe Leonard, Wax Anatomical Figure, full view from above, gelatin silver print, 1990, courtesy of Hauser and Wirth

The truth about the past is not that it is too brief, or too superficial, but only that we, having turned our faces so resolutely away from it, have never demanded from it what it has to give.

James Baldwin, ‘Notes of a Native Son’

To call Zoe Leonard a photographer would be a misleading, or an incomplete descriptive, yet photographic phenomena are at the center of much of her artistic activity. Her work in photography, sculpture, and installation is concerned with what might be called the ‘politics of looking,’ in that she is interested in exploring not only what we see, but also how the forms and contexts of visual material shape what we think we see.

For three decades, Leonard has employed deft gestures that appear relatively simple or straightforward yet reward engaged viewing with revelatory clarity and emotional depth. In projects such as her uncanny photographs of wax anatomical figures from 1990, her mournful installation Strange Fruit from 1992, her growing arrangement of blue suitcases titled 1961, her epic assembly of postcards of Niagara Falls titled You See I am Here After All, or the meditative camera obscura environments she has created recently, Leonard beckons the viewer to observe oneself observing, thereby reviving an awareness of the complex process of perception.

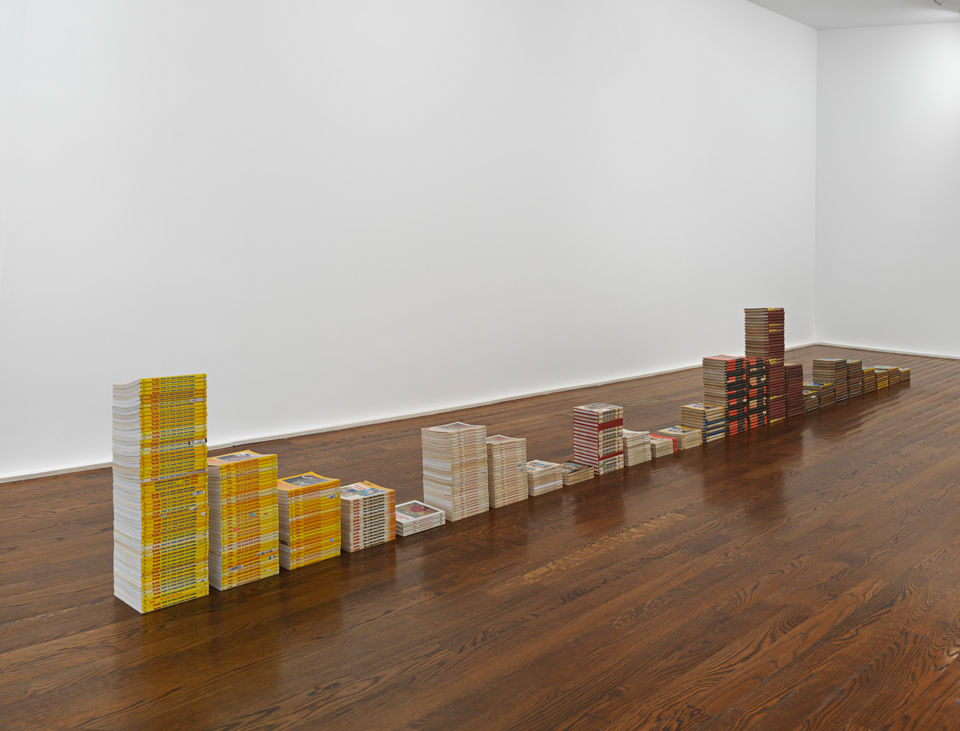

Her new solo exhibition, her first with Hauser and Wirth, is no exception. Titled In the Wake, the show consists of photographs and books installed throughout the three levels of the gallery. Leonard embraces minimalist strategies of presentation; the books are gathered in simple piles, the photographs are behind glass but are unframed and un-matted. There is nothing extraneous or decorative here to distract the viewer from the essential materiality of the images and objects. This unadorned presentation is a challenge, asking us to set aside the precious and spectacular in favor of the direct and plainspoken.

This is not to say the Leonard’s work panders to glib accessibility — she asks us to pay attention, to study, and to ponder subtleties and nuances — activities that are becoming more and more rarified in our everyday lives. To be In the Wake suggests immersion in churning waters after a great ship has passed, to inhabit an aftermath of something momentous, but the title also hints at the duality of life and death — to be (a)wake in the place of mourning. With this in mind, we encounter a selection of World War II-era photographs of Leonard’s European family. The scalloped edges of some of the images remind us that photographs are postage stamps to the future.

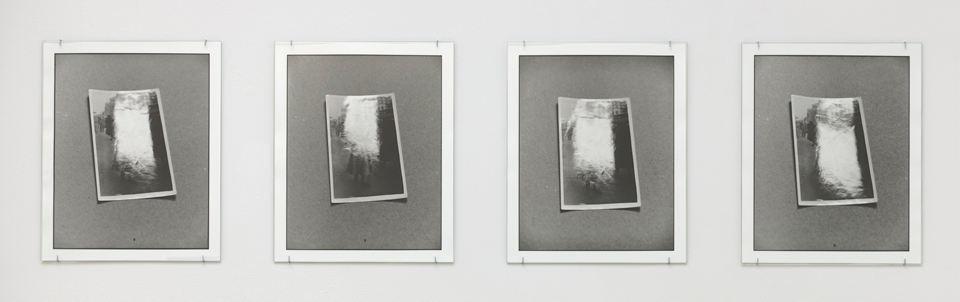

Knowing in hindsight what these people must have faced with the rise of fascism, genocide, war, and displacement, it is particularly poignant to gaze upon a photo a woman and her daughter strolling down an avenue in a carefree fashion. Not content with simply relying on the pathos of the past, Leonard nudges us to think not just about the content of the images but the form and the meaning of photography itself. A photograph is not simply a frozen moment that carries a fixed meaning; a photograph changes through time. It is not only an object and subject to withering, fading — a photograph changes because we change. To photograph a photograph and then to photograph it again, is not simply a tautological exercise, but a gesture that acknowledges that each moment is connected yet discreet and subject to shifting contexts. Leonard’s doubling does not empty the image of meaning but instead reinforces its enigmatic singularity.

A suite of four silver-gelatin prints titled Misia, postwar, shows the same image photographed from above at slightly different angles. A luminous patch of white reflects off the glossy surface of the photographs suggesting they were re-photographed, moments apart, by the light of a window. Each subtle shift of perspective creates a different surface glare — all but obliterating the original image of a woman walking down a street. I stood for a long time in front of this sequence wondering to myself, why do that? Why obscure the image? Why repeat it in such a fashion? As if in answer to my internal interrogation, like the ghost of Walter Benjamin, I imagined a voice in a different register whispering, “The reflected light of now obscures the image of the past.”

Standing like sentinels among the galleries are totemic piles of old photography books that were marketed to serious photography amateurs in the post-war era. With titles such as “This is Photography,” “Dealing with Difficult Situations,” “Evidence in Camera,” and “Total Picture Control,” the books promise that a god-like mastery might be attained through knowledge, discipline, and the right equipment. Through this juxtaposition with her family photographs, Leonard wryly compares the desire for control and mastery in photography to the unpredictability of history itself.

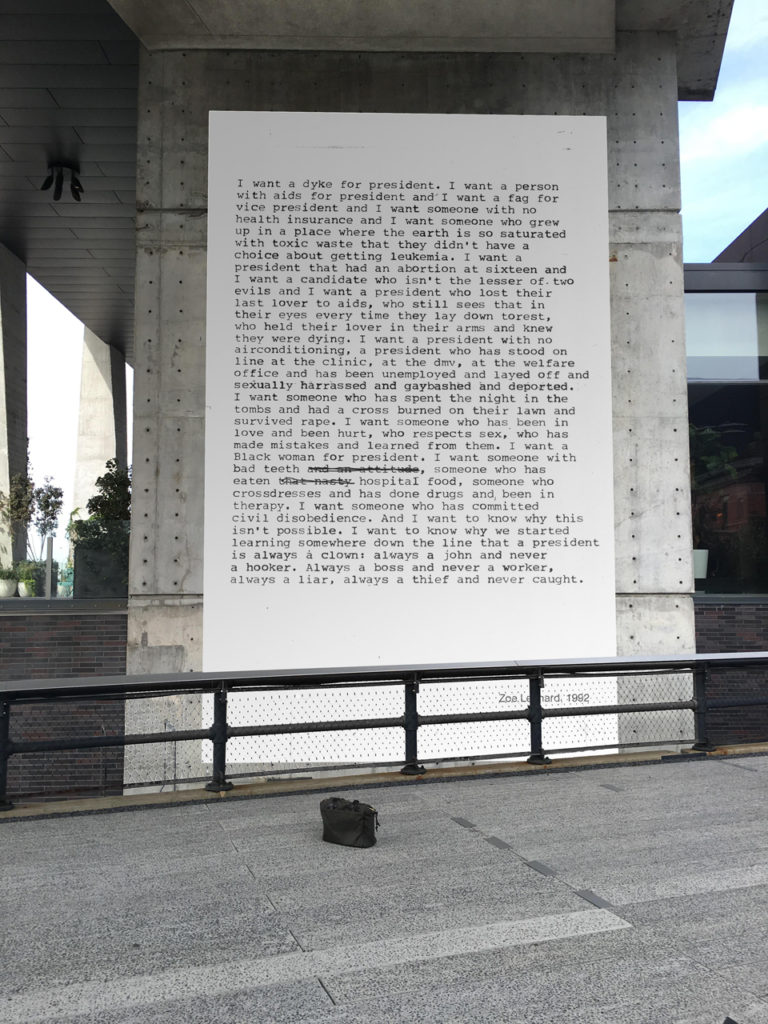

In 1992, Zoe Leonard, typed an urgent manifesto which started with the proclamation “I want a dyke for president.” She followed that introduction with a litany of equally fiery demands – “I want a person with aids for president” and “I want a president who had an abortion at sixteen” and “I want someone with bad teeth, someone who has eaten hospital food, someone who crossdresses and done drugs and has been in therapy. I want someone who has committed civil disobedience and I want to know why this isn’t possible.” This humble artifact, written in response to the banality presidential rhetoric in light of the very real crises facing everyday Americans has, through the years, been touchstone for many artists / activists. It has been resurrected physically and virtually online during this particularly toxic political cycle and is perhaps more relevant than ever. In October, Leonard’s manifesto, enlarged to monumental scale, was pasted up along New York’s High Line reminding us of the redemptive power of directed anger and of truthful things stated simply and directly.

Zoe Leonard, i want a president, on the High Line under the Standard Hotel, October 11 – November 17, 2016

This interview took place initially in Zoe’s home in Brooklyn in early 2015 and was completed at Hauser and Wirth in October 2016.

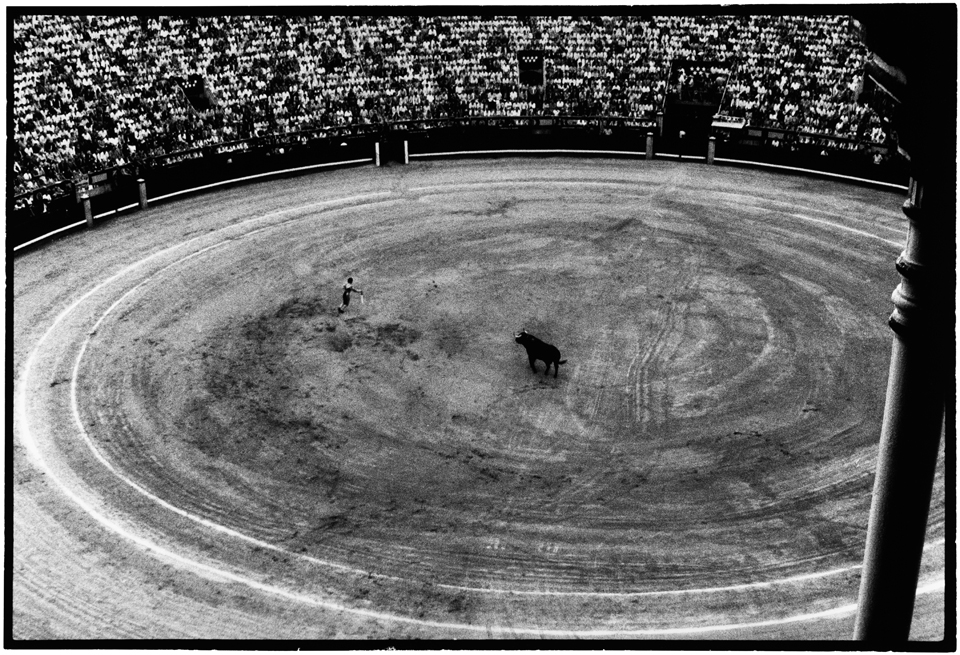

MAD: I want to start in what might be an unexpected place. I was doing some research on depictions of bullfighting in art and I picked up a book titled Bullfighting: A Troubled History. In addition to bullfighting posters, there were the fantastic etchings of Goya, paintings by Picasso and Francis Bacon. Among all of these somewhat expected representations is an image you made of a bullfighting ring, is it in Mexico?

ZL: In Cordoba, Spain.

MAD: Let me describe the picture a little bit. It’s a black and white view of a bullring. Although it is immediately identifiable it is also a very strange and detached image. We can see the matador and the bull near the middle of the ring surrounded by a series of concentric circles that sort of ripple out from the center, which both focuses and distances at the same time. It is as if we are seeing with a telescope and microscope simultaneously. Surrounded as it is in that book by passionate, dramatic and expressionistic images, your photograph is so distinct. I was also struck by how you were able to make an image of something so spectacular and diffuse it somehow so that it becomes something more meditative. Can you talk about that image?

ZL: Sure, I love that you started there and you are right that is a very unexpected place to begin, but is a great entry way into the work. There are a couple of things I could talk about. On one level I would say that those images engage with a set of interests that permeate my work, which is observing and examining how human beings engage with the world. We are born into certain institutions of power whether we want to comply with them or not. The bullfighter exemplifies a certain kind of power dynamic between humans and animals, between performer and spectator.

I have always found those dynamics hard to understand, frustrating, baffling, and maddening. Picking up the camera and looking, taking the time to look at a situation helps me get purchase somehow, get some traction in my surroundings. So that photograph is one of three in which the two main players, the matador and the bull are very small in proportion to the bullring and how the image is framed. Of course, I was in the cheap seats, sitting really far away. So what you are seeing is the game or arrangement of power, it is as much about the arena and the swipe of slightly blurred out faces of the spectators as it is about these two figures. It is also a questioning of the dynamics of photography: who is the subject? Where is the viewer? How does the way in which we arrange our looking reveal our position in the world?

The intention was not to make a critique of bullfighting per se but to look at these ancient forms of engagement. Sometimes my work is a critique, sometimes it’s a love song, but always in there is a curiosity and a desire to understand my own position vis a vis pre-existing structures.

MAD: There is something in your image that creates a moment of quietude in the middle of a spectacle, which is an idea that I think runs through your work.

ZL: I would agree with that. I want to pick up on something you said before when you described the feeling of looking through a telescope and a microscope at the same time. The concentric rings and the circular form of the arena and the distance speak about the apparatus of photography. I am fascinated by the tools that we use to investigate the world. Photography is often understood as an investigatory tool — there is a thwarted desire to arrive at the truth of the thing but you never get there. There is no authoritative ‘there’ there, it’s always relational. So I am interested in photography as an interdependent interaction with the world. The way we produce images has become a central activity to human life; we all take pictures. The images that we take, look at, and share are as much a part of our interaction with each other as our body language, our voice, or our posture in the world. I am interested in thinking about photography as a way to examine who we are and how we live.

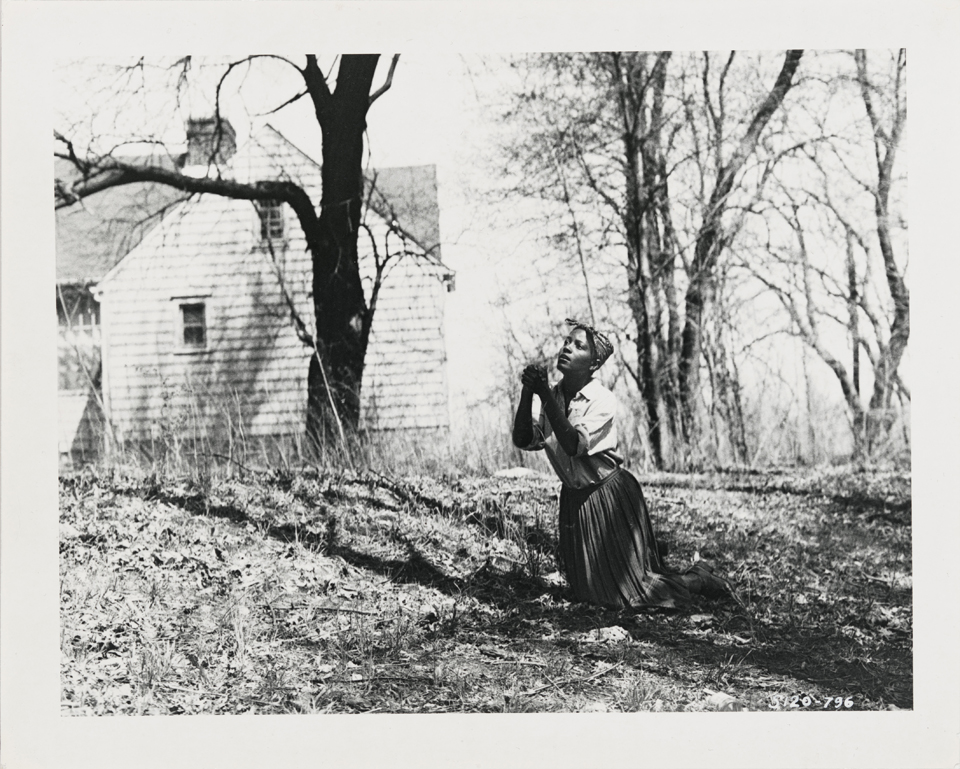

Zoe Leonard, The Fae Richards Photo Archive, 1993-1996, detail. Created for Cheryl Dunye’s film, ‘Watermelon Woman’ (1996). 78 Black and white and 4 color photographs and notebook of typed text, courtesy of the artist

MAD: Let’s talk about you collaboration with Cheryl Dunye on the Fae Richards Photo Archive, which is essentially a fictional archive that you and Cheryl created of an African-American woman who was an actress and a singer in the earlier part of the 20th century. The images are used in her film Watermelon Woman and subsequently exhibited and published as an independent work. Can you describe the genesis of that project?

ZL: I knew Cheryl from around, we had mutual friends, both of us being queer, interested in film and art. I think we met when we were both in the 1993 Whitney Biennial and became friendly. She had an idea for a film that became Watermelon Woman. She asked me to make photographs that would document the life of a fictional character to be used as props in her film.

We had numerous conversations about this character: Fae Richards. We sat down and made a timeline of her life, what year was she born, where did she go to school, how many siblings did she have? We came up with a list of events in her life when she might have been photographed, taking into consideration her class and the historic period of time.

It took me about a year and a half of research, looking at books, spending a lot of time at the Schomburg Center (for Research in Black Culture, at the New York Public Library) and the Lincoln Center for Performing Arts Library. I studied the lives of Butterfly McQueen and Josephine Baker. I was looking at how African American families of modest means were photographed in that period and how Hollywood constructed film stills, glamour shots and what did Black Hollywood photographs look like? How was white skin and black skin photographed in the 1920s and 30s; I mean skin literally. This was a huge problem during that period; films were usually lit so that the white actress was radiant, while the character of the black maid was in the shadow. We embedded those kinds of choices in our process in order to reflect the biases of that time.

Zoe Leonard, The Fae Richards Photo Archive, 1993-1996, detail. Created for Cheryl Dunye’s film, ‘Watermelon Woman’ (1996). 78 Black and white and 4 color photographs and notebook of typed text, courtesy of the artist

Cheryl had zero budget for the film and I, of course, had no money either. But there was a network of friends who helped with research, costumes, props, make-up, and then later printed in the darkroom. While Cheryl was writing the film I was working on the photo archive. As time went on her film became more about the contemporary characters and less about Fae Richards, so she handed this part of the project over to me. I was not only the photographer, but also the director, working in collaboration with a large group of people. After the shoot, there was so much great material, way more than Cheryl needed. As I started to go in the darkroom with it I realized it was its own separate piece and Cheryl agreed.

I think it is important to mention one more thing. There so much about Fae Richards that appealed to me. She is an incredibly juicy, fantastic character, and although she is a fictional character she is absolutely historically possible. The circumstances of her life were in some ways determined by racism, sexism and homophobia and yet she is not a victim. She was often frustrated by the constraints of her time, yet she had an incredible life filled with love and creative expression. We decided to not make it a story of complete abjection and defeat, but instead to show her inventiveness and her agency. I love Fae.

Zoe Leonard, The Fae Richards Photo Archive, 1993-1996, detail. Created for Cheryl Dunye’s film, ‘Watermelon Woman’ (1996). 78 Black and white and 4 color photographs and notebook of typed text, courtesy of the artist

MAD: I think another part of the project’s inventiveness has to do with how the look of the photographs changes throughout the decades; the final images of her sitting on a park bench in her leopard skin coat have a distinctive color of Polaroid instant prints. There is history in the changing nature of photographic technology in terms of its vernacular use. As for the false archive, other artists have employed this strategy although almost exclusively with irony – projects like Fontcuberta’s Fauna or Sultan / Mandel’s Evidence. You reanimate history not in service of irony or with the goal of tricking the viewer, but neither is it sentimental or nostalgic. In The Fae Richard’s Archive you have created an absolutely plausible life that illuminates so many stories that have never been told. The project implies so much about historical erasure.

ZL: Exactly, it is about recovering histories that aren’t documented. Traditionally history is written by the dominant forces. I am interested in pushing against that. Fae became a believable character- a person- not only for Cheryl and me but also for the actress who played her, Lisa Marie Bronson.

Cheryl approached me in 1993, I think, and I identified with the idea of historic erasure. We were coming out of the darkest moment of the AIDS crisis, so many friends, colleagues and comrades were sick or had died and the idea of an erasure of queer history was vivid. It was also a time when the cultural wars around censorship in the arts were raging, the rise of the Christian Right was gathering steam and the idea of historic erasure did not feel like an abstraction, it felt very present. Fae Richards story was not my story but I identified with it.

Zoe Leonard, Strange Fruit, 1992-97 (detail). 297 orange, banana, grapefruit and lemon skins, thread, buttons, zippers, needles, wax, sinew, string, snaps and hooks installed on floor, dimensions variable, courtesy of the artist

MAD: You made the piece Strange Fruit over a period of several years in the early–to-mid-1990s, in which you essentially reassembled the skins and rinds of fruit that had been eaten. It is piece that still provokes, disturbs with all of its evocations of AIDS, Lynching, and the Billie Holiday song in relation to people disappearing. The work combines abjection and tenderness in a way that feels very true to the cultural moment in which it was made. The fruit are transitory and continue to deteriorate and change over time, but your gesture of attempting to mend remains just as emphatic, because that material, the thread, zippers and buttons do not fade. Your gesture to ‘make whole the past’, brings to mind Walter Benjamin’s phrase from his discussion of the Angel of History. I find the piece heartbreaking. Maybe it is difficult for you to talk about the work or maybe you have been asked about it too much…..

ZL: It is gratifying to hear your description of it. The work is very much about the impossibility of holding on to the body, the bodies of people we love, our own bodies. We want to hold on but we can’t. The body allows us to be here but it does not travel through time the way the mind can. Is there a fundamental human condition? If there is, it is that we are mortal and we know it. The fruit is also about sweetness, there is a sweetness, a value and a beauty because you know it is going to end and you should enjoy it. And just because someone is dying or dead does not mean you cannot love them with tenderness and commitment.

I wasn’t trying to make any of those grand claims, I was just sad and confused and a lot of people were dying and one morning after breakfast I sewed up an orange. The next day I did it again and for some reason it felt good. After some time the skins would darken, a friend came over and said ‘What are these?’ and I said ‘I don’t know it’s just something I am doing’ and I kept doing it because it felt good. I started to get excited ‘Oooh pink! Oooh Yellow! Let’s put some buttons on that one.’ I just enjoyed the making. They lined my apartment and studio, it was just a thing I did and over time I slowly realized it was a work.

Zoe Leonard, Strange Fruit, 1992-97 (installation view, Philadelphia Museum of Art). 297 orange, banana, grapefruit and lemon skins, thread, buttons, zippers, needles, wax, sinew, string, snaps and hooks installed on floor, dimensions variable. Photo by Adam Reich, courtesy of the artist

Over the course of a few years I had sewn hundreds of them, there are a few smaller groupings of 4, 5 or 7, but most of them ended up in one large configuration on the floor. I showed them a few different ways and at one point it was like ‘Oh yeah, the floor’, because it’s a garden and its an orchard, its fallen bodies, it’s a graveyard. Its about the ground, its about looking down, and autumn leaves and decay and returning to the soil. But like many things that I’ve made, I didn’t know what I was doing, I didn’t set out with a grand plan. I start out by doing something that feels good, or interesting to me, in this case just comforting. Sewing takes a lot of time and it gave me time to think about people who died. There was a lot of mourning in my life at the time. Not just because of death, but friendships that were broken or in troubled places. You want to recover but you can’t recover, you want to fix it but you can’t fix it, you want to make history whole but you can’t. Even if you sew it up it’s only the peel, the skin, the fruit is gone.

I’m not good with titles; I struggle with them. My dear friend Greg Bordowitz suggested I call it Strange Fruit and at first I thought, no, that song is too specifically about race and lynching but then I realized it was just right. ‘Strange’ is another word for queer and so is ‘fruit.’ I felt that the connections could be loose. I didn’t need my work to be only interpreted in a queer context; there’s a connection between different forms of social violence. The work is about the experience of unrecoverable loss. Eventually the Philadelphia Museum of Art acquired it and it felt like the right place because of the wealth of Cezanne and Duchamp works there; if Cezanne and Duchamp had an art baby together it would be this piece. (Laughter)

The issue of conservation came up during that acquisition and I worked with Christian Schiederman, an extraordinary man and leading thinker in contemporary conservation. He tried many methods including dehydrating the skins and re-infusing them with molecules of a polymer. He finally came up with an incredible process that did not change the look of the pieces at all; it was perfect. And the minute I held it I understood that it wasn’t about finding the right method of conservation, it was that this work shouldn’t be conserved at all. I apologized to him, and said I just think it needs to decay. And to his credit, he said immediately, ‘I think you are right’, he understood that the meaning of the work is that it decays over time and to try to conserve it was a contradiction.

MAD: Photography is so connected to mortality, to time passing, to the temporal and transitory. Also photographs once they have been taken are objects that live it time, as they are handled they age, become brittle, faded or scratched. One would think that photography would be a perfect medium to explore some of these issues. But it is not just about the meaning of the work; it is also about the process. The experience of the artist in the making of a work is seldom discussed. So whatever that repeated gesture of sewing did for you, the way it grounded you or put you in a meditative space, it was essential for the piece to exist.

ZL: We find and build a practice that satisfies us. The amazing luxury of being an artist is that you build a life determined by your interests. A lot of studio time is repetitive labor, for me it is sorting things, stacking things, all of these tasks give you space to contemplate. Like I said about Strange Fruit, I did not get up one day and know that I was going to sew 400 skins of bananas and oranges and make a piece about the dying. I just go to the studio and see what happens.

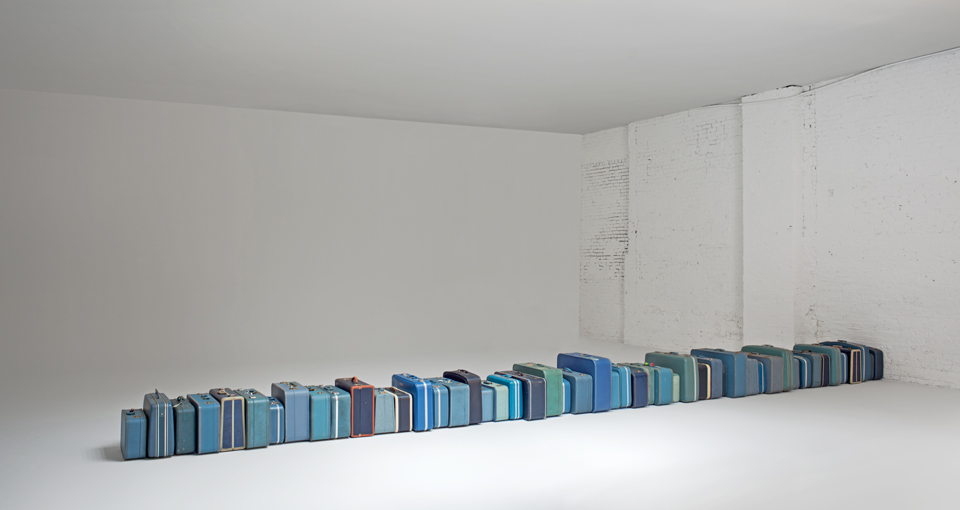

Zoe Leonard, 1961, 2002–ongoing. 41 suitcases, dimensions variable. Photo by Bill Jacobson Studio, courtesy of the artist

MAD: There is sometimes a vernacular aspect to your photography just as there is a vernacular aspect to some of your sculpture, the fruits and the suitcases for example. I saw your suitcase piece in that wonderful show at the Whitney Blues for Smoke. How many suitcases are there?

ZL: The piece is called 1961, which is the year I was born. I add one suitcase every year. I first presented it when I was in my early 40s maybe ten years ago so the piece is bigger now, its 53 suitcases and next September there will be 54, hopefully. (Laughter) Hopefully it’s going to get really long!

MAD: I hope you get to use every blue suitcase in the world. Are you always on the lookout for blue suitcases?

ZL: I have a backlog of them but the nicest thing has started to happen in the last two or three years; friends find blue suitcases and give them to me. That’s not something I ever expected and it makes me so happy. The suitcase I added this year, the 53rd, was given to me by Andrew Ong and his boyfriend George. I got an email from Andy saying they had found a battered blue suitcase on the corner and they brought it home for me. My friend Josiah just gave me one, so now these relationships are being layered into the piece.

But to go back to the vernacular aspect, I love rigorous minimalist work but I am also interested in objects that are used, that are part of everyday life. I think the sculptures that I make are photographic in a certain sense. They are things that are found and rearranged, I am asking you to look at something that was already there. I don’t make a banana out of metal, it’s a banana, and there it is.

MAD: In an interview with Shannon Ebner in Bomb you said you like things to be startling in a quiet kind of way.

ZL: (Laughter) I’ll just say any old thing.

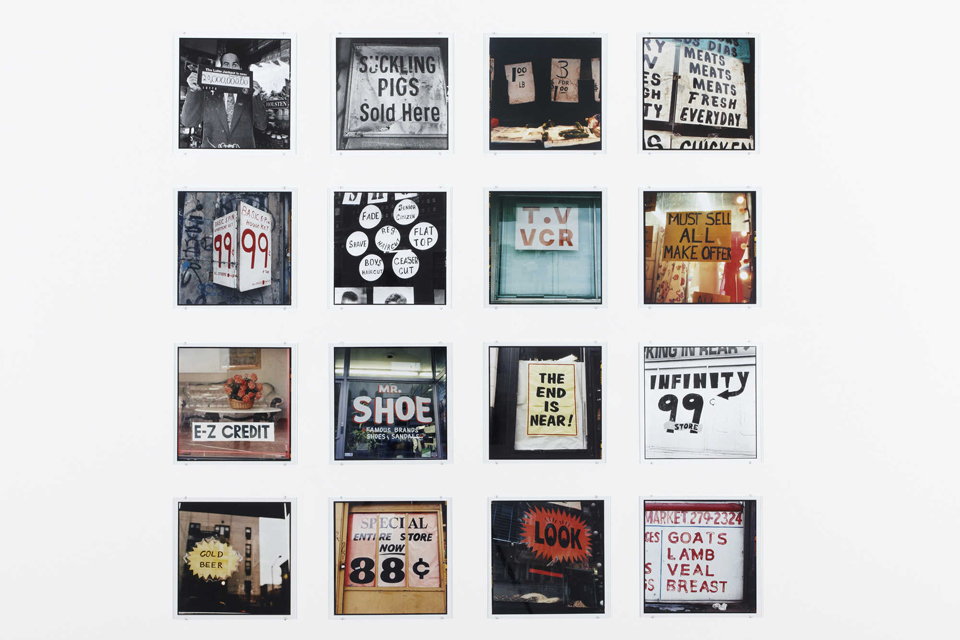

MAD: (Laughter) No, it certainly seems true to me. I think of the camera obscura work in relation to that. But before we discuss that I want to take you back to the Analogue project which is a voluminous series of photographs that you made of storefronts in your old neighborhood of the East Village and then other parts of the world as you traveled. These are not fancy storefronts selling luxury but small-scale commerce, again illuminating the vernacular in architecture and signage. While you work does not mimic, Analogue recalls canonical work by Atget, Sander, Evans, and the Bechers. While the individual images may appear to describe a neutral interest in the quotidian, what is revealed cumulatively is a form of what I would call a ‘politicized looking’.

ZL: I have looked at and thought about all of the artists you mention. I love the audacity and impossibility of these crazy late 19th and early 20th century projects to exhaustively photograph some aspect of society. Or like Walter Benjamin’s Arcades Project that wanted to include everything. Of course they fail in a wonderfully human way, Atget did not succeed in photographing every doorway in Paris. But these projects work because it is not that one succeeds in photographing everything but by extension the viewer moves outward on their own. Analogue in the full installation form is 412 photographs and while I care about each one of those images, how they are composed and printed, what I care about most is what happens to the viewer after they leave. It’s not about standing in front of some ‘masterwork’ of a photograph.

Being immersed in this environment encourages close looking, noticing detail and particularity. When you walk out you may not remember my photographs, but maybe you will look a little closer at your own street, your own life. I am hoping to instigate a kind of attention, a kind of looking that will continue after. There is a contradiction in the idea of photographic typology. I don’t think of Analogue as being about sameness, but difference. In Sander, it is ostensibly about typology but I am not thinking about ‘The Baker’ or ‘The Bricklayer’ in general sociological terms, I am thinking about that particular guy. So you end up thinking about specificity, not type, so in some ways Sander’s work argues against category. When are categories useful and when do they fail us and lead to a kind of fascistic looking?

Zoe Leonard, You see I am here after all, 2008, detail. 3851 postcards Installation view, Dia:Beacon

MAD: It seems to me that your camera obscura projects bring together, in a very subtle way, many of the concerns we have talked about today; the experiential, the quotidian, heightened attention, and the politics of looking. Can you describe your process and way of thinking about the camera obscura pieces?

ZL: I am interested in the interplay of the space, the architecture, the history of any given site as much as the view that is brought in with the lens. The lens carries the image but also carries light. The light that forms the image also illuminates the space. In a traditional camera obscura, and most galleries, the intention is to make the space as neutral as possible. I am interested in the exact opposite, I am interested in how the image that comes in illuminates and reveals the characteristics of the space. So you end up with something that could almost be called a ‘double exposure’.

I am interested in situations that are layered. For example, the camera obscura in Marfa is in an old ice plant that sits across from and parallel to the railroad tracks. This ice plant provided refrigeration for the goods, mostly beef and wool, which were shipped on those trains. So the building and its use are implicitly connected to the image that comes in. I also like the confluence of the camera and the railroad and how those two technologies relate to the American west.

But all of this content is implicit. You can go into the camera obscura and notice, ‘Wow, there are clouds on the floor’ and leave or you can stay in there for hours and hours and think about the railroad and the politics of the settlement of the American west. That material is there and I am trying to draw attention to it, but the work also allows the viewer to engage on their own terms, to have their own experience. Your thoughts can wander. There is no accompanying text that tells you what to do or think.

Zoe Leonard, 100 North Nevill Street, 2013. Lens, darkened room Installation view, detail. Chinati Foundation, Marfa, Texas, Photo by Fredrik Nilsen, courtesy of the artist

MAD: In describing the camera obscura pieces earlier you used the phrase ‘You start to see’. I like that because it implies a process. We assume we just see by opening our eyes, like it’s an involuntary passive act. But in fact seeing is a process in which things are revealed over time. It requires a commitment. It is clear in your work that you are interested in the apparatus of photography and its cultural implications. I read someplace that you said you were not interested in the dominant binaries of photography, such as documentary versus art, or digital versus analog. In fact in your Available Light catalog, the first essay by Diedrich Diedrichsen, he writes about what he calls the ‘Third Photography’, which is outside the art versus journalism binary that has shaped much of the history of photography since its inception.

In your camera obscura pieces there is no ‘decisive moment’, there is no ‘click’, no freezing of time, no fixed image. Instead we are immersed in the phenomenon of light forming into an image. We float in the phenomenon of doubling. In this sense we can escape the acquisitive impulse in photography, which is about ‘taking’ the picture, freezing the moment. In this way photography has thrived in capitalism, feeding and coaxing the acquisitive impulse. Camera obscuras are often understood only as precursors to the invention of photography. But camera obscuras were also used as meditative spaces; they were not just utilitarian aids to drawing.

In another essay in the Available Light catalog Glen Ligon quotes you as describing photography as “a fulcrum point where your view and my view meet.” I like this sense of shared perception that you suggest. And my experience of your camera obscuras is that there is something communal about them. People become hushed, or strangers and friends whisper to each other, one observes how long other people are in there. It’s not like the running time of a movie, where a bunch of strangers sit in the dark for the appointed two hours. It is completely voluntary how long one decides to be immersed and in that time one begins to ‘start to look’; more is revealed the longer we are committed to the experience.

One last comment: I know you are a fan of Svetlana Alpers’ book The Art of Describing: Dutch Art in the 17th Century. One of the many topics she explores is how Dutch art as opposed to Italian art, was not so concerned with narrative, instead it was interested in recording with great acuity the visual and material culture of its time. This is a pre-photographic idea, to observe what is in front of us speaks not only to our personal perception but our cultural life. We live in a culture so proliferate with images that we are in some ways blind. I love how you have taken this anachronistic technology of the camera obscura and resuscitated it in the 21st century to create a space that allows for an optical and cognitive re-set.

ZL: I like what you say about there not being a ‘click.’ There is no click that determines a decisive moment, its not this moment as opposed to that moment. There is an image available but there is no picture. There is no recording, nothing in material form to take with you. When the piece is over the lens comes back to me it goes on a shelf and that’s it. The camera obscura installation at Marfa is 116 feet long by 48 feet deep and when the lens comes out of the window it will fit in a tiny little box on my shelf.

The room is full, dense; all sorts of visual events are happening and changing from moment to moment as time unspools. The longer you stay the more you see. As your eyes adjust, you are able to apprehend more of the image, to discern an image in the darker regions of the room, not just the brightest points. And as you spend time and the room becomes more hushed it heightens your other senses. All of that is happening although in a way nothing is in the room. I like the economy of means.

You have to be there to experience it; the image is fugitive and slips outside the bounds of stability or acquisition. The culture of contemporary museums is about providing the same exact experience for every viewer. The camera obscura installations do not provide that, every single visitor has a different experience. This comes from your subjectivity and the nature of the work itself. It is unfolding in real-time and there are never two moments that are quite the same. It poses a series of questions about unpredictability, variability and the fugitive nature of life. It is also a social experience. The piece belongs to whoever is in the room at that moment.

Zoe Leonard, 945 Madison Avenue, 2014. Lens, darkened room, installation view, detail. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York Photo by Bill Jacobson Studio, courtesy of the artist