Pieter Hugo

Pieter Hugo, from the series 1994. Portrait #16, South Africa, 2016, Digital C-Print © Pieter Hugo, Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

Born in Johannesburg in 1976, Pieter Hugo is perhaps South Africa’s best-known photographer. He is certainly one of the most prolific and challenging photographers working today. His work has been shown in museums all over the world, including solo exhibitions at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the National Portrait Gallery in London, and the Photographic Museum in Stockholm. His work is in the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the San Francisco Museum of Art, the J. Paul Getty Museum, the V&A Museum in London, and many others.

Hugo’s photography deals with “marginalized or unusual groups of people: honey gatherers in Ghana, Nigerian gang members who bring hyenas or baboons on their rounds to collect debts, Boy Scouts in Liberia, taxi washers in Durban, judges in Botswana.” He has stated that his work is informed by the problematic and paradoxical circumstances of his birth. “My homeland is Africa, but I’m white. I feel African, whatever that means, but if you ask anyone in South Africa if I’m African, they will almost certainly say no. I don’t fit into the social topography of my country and that certainly fueled why I became a photographer.”

This conversation took place at Yossi Milo Gallery on January 26, 2017 on the opening day of his new project 1994. The press release for the exhibition states:

Pieter Hugo’s fifth exhibition at the gallery will feature color photographs taken of children born in Rwanda and South Africa after the year 1994, the year of the Rwandan genocides and of the end of Apartheid in South Africa. Wearing often fanciful clothes and posed in nature, each child symbolizes the budding hope of a life unladen by active oppression, yet is rooted inextricably in the landscape into which they were born.

MAD: Before I read the introduction you wrote for your new book / project 1994 — I did my own calculation and figured out that you were 18 years old in 1994. That was the year Nelson Mandela became president, which must have caused a significant shift in your consciousness.

PH: Yes. At that time, there was lots of goodwill and enthusiasm. It was an incredibly liberating period, and not just in terms of rights, but also psychologically. The period of time I grew up in before the end of Apartheid was isolated. A lot of music was boycotted; there were no live bands that came out there, for example. And I guess the period from ’92 until 2000 or around there was a period where this shift happened, and nobody was quite sure as to who was running things, so it was quite anarchic, and very free in a way. And then eventually, I think like what happens after all revolutions, the scum slowly rises to the top again. We see this over and over. But it was interesting growing up in the transition of these two meta- narratives, from one meta-narrative to another meta-narrative — from the Apartheid period to the Mandela period.

MAD: 1994 was also the year of the Rwandan Genocide. On the one hand there must have been so much hope with Mandela, on the other there is the horror of Rwanda.

PH: I have a sense that we had more news about it in South Africa generally than in Western media. I remember seeing daily broadcasts on television. A lot of South Africans and fellow journalists went there. I think because it was in vague proximity we were just more conscious of what was happening there. But the narrative — the politics — of what was happening was being articulated in the same way, which was that it was a tribal conflict as opposed to the geopolitical conflict having to do with the legacy of French colonialism.

MAD: At the time, when you were 18, were you politically conscious of that difference in how it was represented in the media?

PH: No, I think growing up in South Africa when I grew up, to travel as a white person with a South African passport in Africa was quite difficult. So it’s only after 1994 that suddenly a lot of doors and opportunities opened up. And I think that during the time I became a photographer and started working as a photojournalist, I would get a lot of work around Africa, clearly because people somehow thought that, “He’s African, he’s got a sense of understanding of the narrative.” When in fact, it was cheaper to fly from France to Nigeria, than it was for me to fly to do work there.

MAD: So in some ways you were more isolated from what was going on in the rest of Africa because you were in South Africa. A French photographer would have more freedom to travel around in Africa, at least in Francophone countries.

PH: Yes, I mean, you’re part of the topography, but you don’t belong to it.

Pieter Hugo, from the series Kin. Loyiso Mayga, Wandise Ngcama, Lunga White, Luyanda Mzantsi, and Khungsile Mdolo after their initiation ceremony in Mthatha, South Africa, 2008

MAD: In one of your interviews you used a very vivid phrase to describe this – was it ‘cultural driftwood’?

PH: Colonial driftwood. I’m the artifact of a colonial experiment, that didn’t really work out. [Laughs]. I definitely feel that in some ways.

MAD: And this continues to be a dilemma?

PH: It’s a constant battle as to what you can claim and when and where your place is to be assertive, and when to apologize. I think growing up in the period I did, everything is just super politicized. And to me, it’s a bit of a sword hanging over my head all the time. And I think over South African photography in general, if one looks at the prolific figures that have come out of there. All of it is very political. And in some ways it makes for very important, observant work, but in many ways it’s incredibly limiting. If your work is not political, it’s expedient, frivolous.

MAD: You’re expected to speak to a situation, or to a history.

PH: To a history, yeah. It definitely comes from a socially engaged and committed tradition.

MAD: And you have a push-pull about this expectation.

PH: I used to be very conflicted about it. But now I quite enjoy being able to play with that expectation. I think what’s interesting to me about photography is the space it sets between document and art, and I’m still very much enjoying work that’s about engaging with the world and stepping into it, but I also like the idea of being able to play with that. Sometimes people don’t get that. [Laughs.] Unfortunately.

MAD: You didn’t study photography formally, but I would imagine now that with your career, that you regularly give lectures about your work at universities and art schools.

PH: Occasionally, more museums than universities. But I do workshops occasionally.

MAD: I’m just curious about your relationship to the academy. How much you feel that training is necessary. Especially since you don’t come from that tradition?

PH: In South Africa, it seems to me, that of the photographers who have succeeded, the majority of them did not come from a formal art academy background. And the ones who did succeeded despite the academy. I’m sure there are some professors who I’m friends with who are going to call bullshit on me. The nice thing about photography is really that in its craft, there are only three or four variables, really, which is what is fantastic about it. It makes it very easy, democratic, and accessible. But that’s also its curse in a way. Everybody’s a photographer, and everybody’s got an opinion about it.

MAD: (Laughter). But I like that.

PH: So do I, but the problem is the language that you and I use to talk about photography is very different to what the layman reads photography. It’s almost a different dialect, different languages. And this is problematic. Still to this day, in a lecture, the first question I am often asked is what camera I use – then you know you’re in the wrong place.

MAD: (Laughter) Somebody is going to inevitably ask that question, it is like the plague of photographers for decades.

PH: [Robotic] I use a camera.

MAD: I was actually at a Robert Frank lecture and somebody asked him that.

PH: Oh yeah? And what did he say?

MAD: He just shook his head. [Both laugh.] Can you tell me what was your first series or completed project? Was it the Rwanda images?

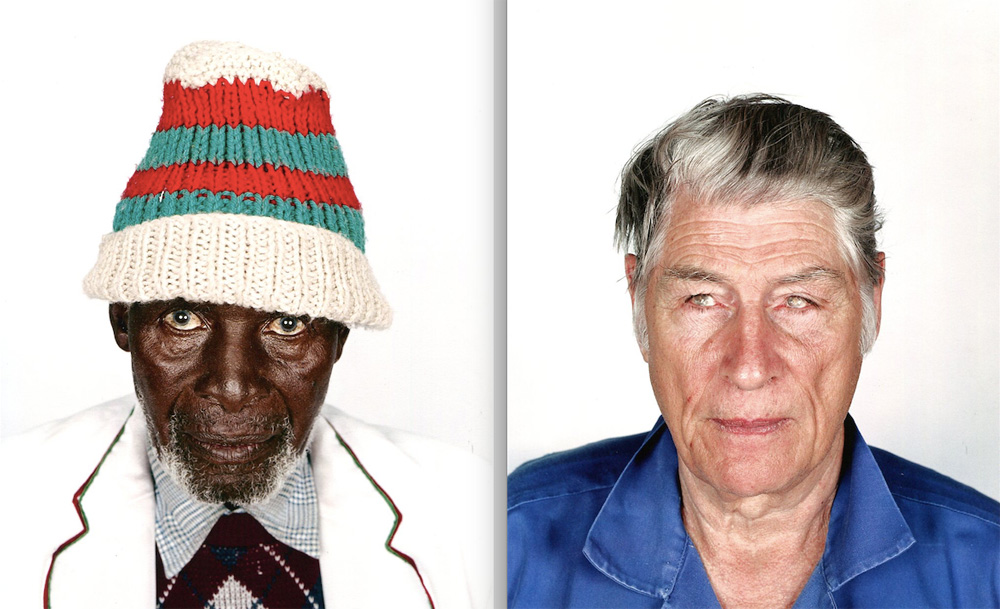

Pieter Hugo, from the series Looking Aside. Left, Aron Twala, Vrede, 2006. Right, Justus Wilhelm Reitz, Carnarvon, 2005.

PH: No, it was a series called Looking Aside. When I grew up, all I wanted to be was a photographer. I didn’t even know that art photography existed, it didn’t occur to me. What attracted me to photography was the fact that it was out in the world, and it was physical, and engaged. All these things attracted me to the medium. I didn’t want to sit in a studio; I didn’t want to sit in an office. So, for a long period I worked as a documentary photographer, very much an assignment photographer, first at newspapers, then at magazines. Looking Aside was the first project that I felt resolved itself and ended up as a photo book. I mean, that was really my life’s ideal, to publish a photo book. So when that finally happened, I had to find some new ambitions.

MAD: And what was that? Did you feel restrained by how much of photo- journalism is assignment driven?

PH: Yeah, what started happening was that I felt like a propaganda artist of sorts. That I was taking pictures for articles that were already written and the journalist’s mind was already made up. For example, I would get assignments from UNICEF saying, “Go to Rwanda, find a woman who was raped in the genocide, pregnant, contracted HIV, had a child, is now receiving anti-retrovirals because of UNICEF, and is leading happy life.” You know? It’s like, I can make great, beautiful pictures illustrating all these points, but sometimes I would find that this is not my experience. My experience is much more opaque, complicated. So I started becoming more aware of the limitations of my practice.

And that’s how that shift started happening. I wanted to go to Rwanda. I’d worked for numerous publications. It was the tenth year anniversary of the genocide, and I just couldn’t get anyone to commission me to go there. There was a reaction against Afro-pessimism and editors wanted ten years of democracy in South Africa covered. So I packed my bags and went to Rwanda for three months and sort of approached the scene without any clear idea of exactly what I was going to do.

Pieter Hugo, from the series Looking Aside. Thami Mawe, Johannesburg, 2003. Archival Pigment Print © Pieter Hugo, Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

MAD: A long-term commitment to a subject, following it where it takes you rather than a pre-existing editorial slant, distinguishes conventional photojournalism from a project that can reveal deeper meaning.

PH: I sat on those photos for ten years before I even published them. But I think for me that is one of those differences between assignment journalism and art photography. The fact that you can take time to look at your pictures, review them, analyze them, it becomes possible to imbue them with meaning that may be deeper, more nuanced.

MAD: There is a stillness that seems to hover on the edges of your photographs. That has to do with maybe the large format process. But also there’s a sense that we’re looking at something for a long time. This is not a quick candid snap; your pictures invite a level of contemplation.

PH: I think that is what I am good at. Creating stillness in an anarchic atmosphere. [Laughter)

MAD: I want to ask you about something you said that has been widely quoted in which you express a deep skepticism about the efficacy of photography in helping solve problems….

PH: [Laughing] That’s the one thing I said when I was drunk that’s going to haunt me forever!

MAD: I’ve said many worse things, and I think the skepticism is healthy…

PH: That’s what I was speaking about with the two different languages. You and I know that a photograph can never represent anything but the surface of something. When we read imagery, it’s as much about the baggage that we bring to the picture as to what is pictured or represented. One of the portraits in 1994—the child lying in the Earth—by some people could be read as demeaning and degrading. And some people will see it as me speaking about the Rwandan genocide and the landscape is the site of the atrocity—you know, there’s a different, depends on from what level you are looking at the imagery. But I think having a healthy distrust of photography is good. I think if you have been doing it for twenty-odd years and you don’t have a distrust, you are either naive or overly enthusiastic.

MAD: I think as an artist, as a photographic artist, skepticism is really important. While I am aware of theoretical critiques, and the limitations of photography, I also think the critique dismisses or underestimates the power of photography to reveal and empower on the personal level and within the public sphere.

PH: Well, I think that if I had gone to university, and had been confronted with those types of critiques before becoming a practitioner, it would have paralyzed me. And I’m very glad that I have had to deal with it during practice rather than before even going on that journey.

MAD: Sometimes people have to learn to succeed despite their university training. I am not suggesting that we teach nothing about the history and ethics of representation, but sometimes seeds of doubt can be planted too early, before substantial experience can lead to a deeper commitment to the medium. Sometimes university or art school training can be quite paralyzing.

PH: I encounter it all the time, I do. Particularly in undergraduates, because by the time you get to post graduates, you’ve hopefully found your voice or your journey, but I often find with undergraduate students, arguments they are having with themselves. This is not the function of art. I tell them to make first, analyze later.

MAD: One of the things I love about your work is that your photographs prove the power of photography. They have an unflinching quality that suggests something that Diane Arbus talked about, to make the familiar strange and the strange familiar. So it creates this sort of image that doesn’t resolve. Your images can’t be easily read or digested, which creates a resonance. I think that’s where the power of your work is.

What is so remarkable about the photographs in your current show here at Yossi Milo is the singularity. They are individual portraits in these close-up environments that are like still lives in a way. They aren’t grandiose or sublime landscapes, but intimate encounters with an individual in a specific slide of the earth.

PH: Thanks, I appreciate it. It’s not easy photographing kids, I can say that.

MAD: To get beyond the sentimental?

PH: To get beyond the sentimental but also there’s an honesty in kids that you can’t create. They don’t model, they are what they are. So for every twenty kids that you photograph, only one will have that energy. That I’m specifically looking for. So for this series there was a real numbers game being played. I photographed a lot to be able to get it.

MAD: In Camera Lucida Barthes talks about a significant difference between photography and film is that one can look as long as one desires at a photograph. In film one image is constantly replaced by the next.

So one can have a contemplative relationship to a photograph. It gives me permission to look in a way that normally in encounters in the world can’t exist because it would be rude, or it would be impossible, to gaze at a stranger so intently.

PH: Absolutely. I think there’s something about that desire to look, which I’ve tried to find in my portraits. 90% of the time when I photograph someone, the gaze is returned. And that’s very important to me. I think somehow I want to make pictures that hold you, and give you space to escape.

MAD: One of the things I think you addressed in some article or interview elsewhere, is the agency of the person, that they give you permission, right? Because the critique of representation is often reduced to a simplistic question —‘who are you to objectify these people?’ — as if to suggest that people are just passive victims of the photographer. Obviously that can be an issue in photography but in photographs like yours there’s no way that those photographs happened without the other person’s cooperation.

PH: If someone doesn’t want to be photographed, I don’t want to photograph them. I’ve taken enough, I’ve accomplished enough photographs in my life to know it’s every way around you, that one moment is not the definitive picture, I would rather let someone be than transgress someone’s space. Sometimes people aren’t happy with the result. That’s a whole other story, of course.

Pieter Hugo, from the series Nollywood. Left, Obechukwu Nwoye, Enugu, Nigeria, 2008. Right, Escort Kama, Enugu,Nigeria, 2008.

MAD: I wanted to read you a couple of quotes about photography from Susan Sontag and Larry Sultan to see how you might respond. The Sontag quote is, “Harrowing photographs do not inevitably lose their power to shock, but they are not much help if the task is to understand. Narratives make us understand. Photographs do something else. They haunt us.”

Then the Larry Sultan quote, is: “Like a ventriloquist that laughs at his dummy’s joke, I keep trying to make photographs that seduce me into believing the image. All the time knowing better, but believing anyway.”

PH: (Laughs) That pretty much hits the nail on the head.

MAD: I thought about both of those quotes when I was reading some of the things you had said about conflict and paradox in your work.

PH: It is like Nietzsche declaring that God is dead and then spending his entire life writing about it.

MAD: Every photograph then, to some extent, is an acknowledgement of skepticism, yet is also an attempt to connect.

PH: Well, it is. There’s something interesting to me about the process, whether I’m photographing children or politicians or a guy working in a computer dumpsite. In the process of making a portrait, there is a very brief moment when economic, linguistic, or any cultural divide gets bridged—albeit briefly… So even though I’m cynical about the social implications of photography, the social activist potential, I think my pictures are still humanist, because they are still dealing with people. There is a human interaction.

Pieter Hugo, from the series 1994. Portrait #10, Rwanda, 2015. Digital C-Print © Pieter Hugo, Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

MAD: So, this is kind of a pretentious question, but I was thinking about your work in relationship to August Sander. While you may not have the sociological agenda of Sander, there is something equally epic, I think, about your project. Perhaps in the future your photographs will be viewed as a particular collective portrait of a moment in time in Southern Africa. And I know that sounds sort of grandiose, but does that resonate with you?

PH: Well, I’ve never thought of it that way, but thank you! You know, I often wonder whether August Sander actually had that grand ambition, or if he just had to frame what he was doing anyway.

MAD: He was, as far as I know, was very influenced by the Neue Sachlichkeit or New Objectivity movement, which was a reaction against the emotional and esthetic excesses of Expressionism. He wanted photography to serve the social sciences. He photographed people with a sociological agenda; individuals were representations of types within a society. He rarely gave his subjects names. Yet one of the reasons he is such a fantastic photographer is that in addition to his sociological bias, he approached each person on their own terms to some extent. There’s no explicit judgment, whether he is photographing a baker or a proto-Nazi. And there’s a sense of dignity without being ennobling or sentimental. And that world he photographed, Weimar Germany, was soon to be destroyed

PH: The first proper paycheck I got from work, I went to buy the full set of August Sander images.

Pieter Hugo, from the series The Hyena and Other Men. Abdullahi Mohammed with Mainasara, Lagos, Nigeria, 2007. Digital C-Print © Pieter Hugo, Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

MAD: You’re probably sick of talking about the hyena men that you photographed in Nigeria?

PH: I was sick, I go through cycles.

MAD: In those photographs I feel like I’m looking at a medieval beast. It’s a strange and odd creature, and then the way you photograph them and then the humans that they interact with. There’s this juxtaposition of scale, and not only scale in relation to bodies, but in relation to how bodies interact with one another. The images are extraordinary, I know I am exoticizing yet….

PH: But you do not get more self-exoticizing than these guys. It’s part of their act that they are all ripped. They work out, they are super muscular. They wear flamboyant embroidered clothing, and have muzzled but massive West African hyenas. They put the chains—the chains that they put them on are super large, metallic links. A friend of mine found a photograph from the turn of the century of a family in West Africa with exactly the same dresses and hyenas in the same muzzles. And when I asked these guys if this is an old tradition, they said no.

MAD: But these Nigerian guys are clearly marginal in terms of the economy, yet Nigeria is the world’s fourth largest economy, an oil economy, but these guys live as medieval entertainers. Is this a family trade? How do you become this?

PH: It’s a family trade. They’re all related to each other. They remind me—the closest thing I can relate them to are the Roma traveling people, who had dancing bears on chains, that kept moving around day to day. Probably because people only come see a show once or twice and then you’ve exhausted your customers. But also probably because if they stay too long, they’d be chased out. When I first photographed those guys I went with a box of large format film—I don’t know what I was thinking. I ended up shooting with medium format although I only had 20 rolls.

Pieter Hugo, from the series The Hyena and Other Men. Mummy Ahmadu and Mallam Mantari Lamal with Mainasara, Abuja, Nigeria, 2005. Digital C-Print © Pieter Hugo, Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

MAD: There’s that story you tell about hiding in the bushes with some guys and their hyenas while someone on the road tried to flag a taxi.

PH: Yeah, we needed to get somewhere. Transport happens in these minibuses. So we were all hiding, a minibus pulls over, and we spoke to him and chartered the bus, then everybody jumped in quickly, including the two hyenas in the trunk, and like three baboons and a few rock pythons. I was sitting in the front next to the driver with a baboon by my feet. [Laughs] This guy could not—I mean, I think he was just glad for the work. It was a ten-hour journey. Too terrified to not do it. And he drove as fast as he could.

MAD: And you didn’t know if the driver or the baboon was more terrified?

PH: Well it was just this moment of looking at the baboon and just—there’s a famous Rilke poem, “My dear God, there’s only a small divided wall between us.” But the same applies to men and animals, and that was one of those moments where I had this anthropomorphic moment when I could see that the baboon was aware of its own mortality, like “Oh my god, are we all going to die here?”

Pieter Hugo, from the series 1994. Portrait #19, South Africa, 2016. Digital C-Print © Pieter Hugo, Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

MAD: Let’s talk about the show here at Yossi Milo. It’s called 1994 and it features large-scale photographs of children from South Africa and Rwanda. I liked what you’d said about children being without history, they don’t have the baggage of adults. So in that sense you see them as all potential, ahistorical to some extent. But it is difficult for viewers not to project history upon them.

PH: Which is why I photographed them in nature, as opposed to urban settings. There’s something interesting about that space of nature where, if you leave a city, the first belt of nature around the city is a threatening space. Where the gypsies live. Where people dump bodies and things like that. And then you move farther out. The more the space becomes Arcadian and idyllic. We return to the environment, our natural environment. That’s something that was on my mind and then of course this ties into my experience when I worked in Rwanda at the beginning.

At that time in 1994 there were still bodies everywhere. Swimming through a lake or going for a walk through a plantation was a threatening, psychologically heavy experience, because there are still artifacts of the genocide. The vestiges are still there. And then furthermore, being white—this is a big fear I think, around being a white South Africa, the colonial history and the repercussions thereof, around the idea of land and who owns land. Farm seizures in Zimbabwe, it’s very much what ties someone to nationhood, identity—it’s the right to own or claim land, in a way. So these things are playing out in those photos.

Then there’s the clothing. I purposefully avoid clothing with any sort of branding on it. I don’t want to distract in any way. I often ask children to wear the clothes that they would wear on a Sunday to church or to a wedding — to put on their best.

Pieter Hugo, from the series 1994. Portrait #7, Rwanda, 2014 Digital C-Print © Pieter Hugo, Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

MAD: One of the children is wearing a gold sequined thing as she reclines in the earth, the red earth.

PH: Yeah, a super red earth. A rich soil. But then also a lot of the clothes were given to the kids. Or bought in markets in Rwanda, donated from European and American countries, that end up in these markets in Africa. They get a whole other life there. If we wore them here it would be ironic and something an art student would wear. It’s often clothes of synthetic material that lasts much longer than cotton clothing, etc. Which also reminds me of images from the Balkan War of bodies that were being exhumed, the clothing that was often all that remained because it would be this synthetic material, tracksuits and fatigues, things like that. So it’s tapping into my memory of that period.

MAD: But they show up wearing whatever they are wearing.

PH: Sometimes there might be a bit of help.

Pieter Hugo, from the series 1994. Portrait #1, Rwanda, 2014. Digital C-Print © Pieter Hugo, Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

MAD: There’s the one image in which the child is wearing a very large jacket.

PH: That was one of the first pictures and he was dressed like that. I was in Rwanda photographing a commission for the criminal court, which I eventually sold to the New York Times Magazine — a series of portraits of the perpetrators and survivors of the genocide. People directly related to each other who were neighbors, killed each other’s children. The story was about the potential of reconciliation, to forgive. While making these portraits, which was an intense experience because you are listening to stories while you are making the photographs. It’s quite hard to place yourself in these people’s positions, and you wonder how can they sit there and have this conversation without breaking down. It was during the school holidays in Rwanda, so the kids came around, curious to see what we were doing. And I photographed the girl in the pink dress first; she was playing with a bunch of kids including the boy with the huge jacket. Those two portraits were the first two and they just stuck with me. Immediately after that I made the portrait of my daughter standing with the geranium crown. And I thought, here’s something, here’s a real challenge, photographing children beginning their lives after the year 1994.

Pieter Hugo, from the series 1994. Portrait #44, South Africa, 2016. Digital C-Print © Pieter Hugo, Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York