Penelope Umbrico

Things are going well for Penelope Umbrico right now. This spring Aperture published her stunning monograph, in 2010 she was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship, her work was featured in the New York Times magazine and is receiving increasing international attention. Not to be simplistic about it, but Penelope is a photographer of the internet era. She hunts and gathers images from the internet, assembling the most banal artifacts from online catalogs and image sites such as Flickr and Craigslist. In doing so she cumulatively transforms the insubstantial pixelated fragments into immersive meditations on what beauty, identity, loneliness and desire might look like in the digital age. Penelope is also a dedicated teacher, She taught at Harvard in 2010, was the chair of photography in the Bard MFA program, and is currently on the faculties of both the graduate and undergraduate programs at SVA. This conversation took place in her Brooklyn studio on May 11, 2011.

MAD – You use the word narrative a lot when describing your work especially with this book – can you talk about what that word means to you?

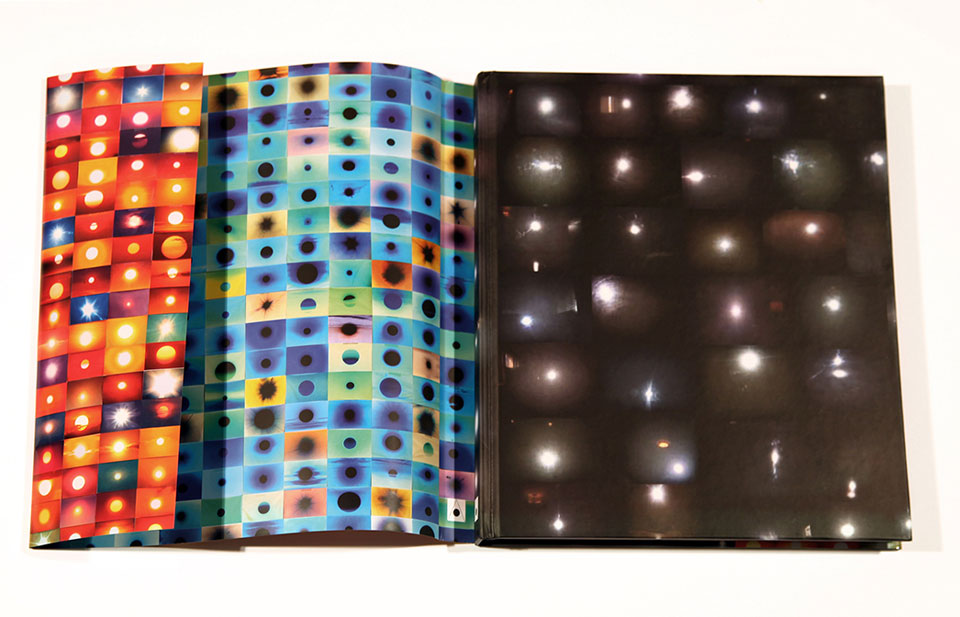

PU – I mean that the book tells a story – not necessarily a plot-driven story – but the work in it sets up a set of expectations that shift over the course of the pages and ends somewhere that may not have been expected. So there is a narrative relationship between things, between images and ideas. Any one the bodies of work does not have a narrative, like the suns…….

MAD – Right, its not a series of suns getting progressively closer to the horizon line – they are all suns in the middle of the frame…

PU – Right if the suns started at the top of the frame and incrementally moved closer to the bottom that would be a kind of narrative within the body of work

MAD – In your book there are 16 pages devoted to setting suns – how do you know how many there should be?

PU – Well its always a different size – depending on where and how its presented – also the number of setting suns available on Flickr is always growing – in 2006 there were 500,000, now there are more than 9 million. I have 2,500 sun images that I’ve cropped from these sunsets and since the images never repeat in any one installation, I might have to search sunsets on Flickr again for more suns if I’m given the opportunity to install on a larger wall than I have work for.

MAD – I like how you include excerpts from an online discussion board on Flickr in which some people are posting disses of you because you are stealing other people’s photos.

PU – Yes – and I am accused of being lazy! But then they decide that they like the work anyway! But some photographers cannot accept the fact that I am treating images this way and I think it has something to do with the anxiety around authorship in photography – that anxiety that has haunted photography since the beginning, along with its fight for a claim to artistic legitimacy. I love the fact that everyone takes pictures of sunsets – that we are part of this collective practice of photographing sunsets, yet there is still this pressing need to claim that act as original and authored “This is my picture of a sunset, I made it!”

I also really love that people are taking pictures of themselves in front of my work as if they were actually standing in front of a sunset, and then they post their portraits – I’ve found a number of these pictures (of people in front of my “suns”), on blogs, Flickr, Facebook – they have no problem using my work as part of their images. And I found pictures on Flickr of people taking pictures of people photographing their friends standing in front of my pictures. Laughter

MAD – It’s a constant loop of rephotography. Just before I came to meet you I was just at MoMA to see the Francis Alyss show and the German Expressionist Print show, I took a walk through some of the galleries and I passed by Wyeth’s Christina’s World and it was surrounded – an arcing crowd huddling to get closer – with dozens of hands holding up cameras and cell phones to photograph it – so I photographed the people photographing the painting. I wonder how anyone gets in a snit about originality anymore. Anyway, I was thinking about the popularity of your sunset pictures and I was wondering if this would be your ‘Moonrise over Hernandez” that image that became emblematic for Ansel Adams. – Laughter

PU – That’s a really good question, in a way I am, or am beginning to be haunted by the popularity of that piece. On the one hand its kind of annoying that everyone likes it so much but on the other hand its not like ‘Moonrise’ in the sense that my piece is about how universally popular the sun, as subject, is, evidenced by how many sunset pictures there are on Flickr.

MAD – I think all of the work I know of yours employs appropriated imagery, but I am curious, did you ever work with a camera in the conventional sense, you know, sling the 35mm around your neck and head into the world looking for things to photograph?

PU – Yes, I still do, I always have – I have a project on my website right now called Jasper Walking which involves hundreds of pictures taken while walking my dog. This became a kind of project when I realized that a bunch of pictures I had taken in the country one day all had my dogs nose in them… even though he was off leash. He followed me around constantly. He thought he’s my shadow, or that it was his job to be at my side at all times. Taking those pictures became symbolic to me of his insistent presence, his loyalty, and somehow his mortality…. But in a way, my other work is fairly conventional from a photographic point of view as well – I just head into virtual spaces, rather than the outside world, looking for things to photograph. I use the screen grab or the crop tool the way I’d frame a picture with a camera on the street.

MAD – When did the work with online sources begin?

PU – With the “Suns from Flickr” and the “Views from the Internet”, I had been working with imagery from home décor mail-order catalogs with a series of Views through the windows in the images of rooms in the catalogs. This work was about the idea of escape – how one could move though the idealized rooms in these places and virtually exit right out the windows into a wonderland kind of space. And when I started working with the suns in 2006 I realized that the views from home décor websites on the Internet are so much more interesting in this regard than views from print media.

MAD – What about the mirror pieces – are they from the Internet or printed catalogs?

PU – From catalogs originally but for the Rencontres d’Arles photo festival I proposed to remake the piece using mirrors found on the internet. They are so different – moving from the dot screen to the pixel grid – such a different kind of imagery. That project was originally about erasing the viewer. As you look through these catalogs you lose yourself and vicariously become someone else, as you fantasize about living in a completely different environment. But when you look into the mirrors in these environments you are not reflected back, the objects replace you. So what I did was to take mirrors from these catalogs – blow them up, cut them to the shape and turn them into non-reflecting objects in the gallery space – sculptures of mirrors. With the online home décor websites that idea of erasure is magnified – you can lose yourself much more easily, faster and for longer periods of time in an online environment.

MAD – Did you study photography?

PU – As an undergraduate I did at the Ontario College of Art but my focus was on painting. 6 years later I did my MFA in Fine Arts at SVA and started to make photographs again there.

MAD – What kind of photographs were you making?

PU – Big blurry dumb photographs – laughter. I was interested in a subversive relationship to the medium, or maybe not the medium itself, but to the machine. The idea that there is this tool that we make that we use to replicate the world, in order to see things the way we see things. Its curious – the idea of fidelity and how it has dominated the history of the medium and I wanted to turn that on its head.

MAD – Were you unsatisfied with that work at the time?

PU – No I was excited about it – I was coming out of painting and it was interesting to be using a medium that had a certain claim to veracity. I have always been more interested in how we as a culture see things than how I see in particular. I am not interested in producing work that shows how I see, in that literal manner that photographs can confirm.

MAD – That’s interesting – I like the way you describe the camera as this device we invented to replicate the way we see the world. It implies a kind of narcissism that we have created this elaborate industry to reflect back and constantly reaffirm how we see.

PU – That goes back to the anxiety we were talking about – that we need a device that re-affirms our existence, that reassures us and soothes our anxiety around this. I mean I am generalizing and obviously artists use the camera differently, but again I am interested in the mainstream use of the camera – that need to get the picture, the proof, the feeling of relief once the picture has been taken and that’s all that matters.

MAD – I am reminded of Sontag’s observation in ‘In Plato’s Cave’ that people, especially from highly industrialized nations, use the camera especially when traveling or on vacation as a way to ease their anxiety about not working, it gives them something to ‘do’.

PU – Yes… and it allows us to own what’s in front of us, take control of it, and make it our own object – the unknown, known. I think it’s why sunset pictures are so popular.

MAD – One of the interesting things about your work is that you take virtual things and give them form in the real world – you re-objectify them in a way. The mirrors for example, what starts as small details in print catalogs or online home décor sites are re-presented as scaled-up objects with real physical presence. The suns as well, a sunset image on Flickr ends up being part of a large-scale immersive environment. That same impulse to make images physical is applied to the conceptual framework for your book. With the Nicholson Baker essay, Books as Furniture, you could have had it reformatted and printed so that it may have taken four pages but instead you devote 24 pages of an scan of the essay from a clearly used book with its slightly yellowing pages. I find that extraordinary. I mean its almost crazy – if you think of having an Aperture monograph as a kind of high-point in one’s career – to give up so much of its real estate to a scan of someone else’s words. I think that decision speaks to the integrity of the conceptual foundations of your work, its not about ‘you’ per se, it is about the right form for the idea.

PU – I am using the scan as a way of talking about the book as an object. It becomes a piece in its own right. One of my projects in the book involves looking at the way books function as a kind of furniture in home décor catalogs, and Baker’s piece is the literary equivalent. I love that it equally talks about, and becomes the thing it talks about, in my book. All of my photographic work uses other people’s work in some way and I wanted to do that with the texts as well. I didn’t want anything written about my work in the way a conventional monograph has a writer introduce the work. It made sense that the writing with the work be treated the same way as the work – the words are not directly about my work – they’re in conversation with it. In the second part of the book, the appendix-like section where there are a variety of people from various contexts asking me questions, the writing is in the first-person (“I”, “you”) – it’s a kind of interview collage.

MAD – Lyle Rexer asks you the question I would have asked: “Do you believe in ghosts?” and “What about electronic ghosts?”

PU – I am really interested in the idea of the ghost and the idea of erasure and the loss of subject-hood that the mirror project started with. And I think the avatars that we are online are ghosts in a sense and that we inhabit a kind of ghostly mental space when we are on the Internet. My answer to Lyle was that you couldn’t really believe in ghosts when you are the ghost.

MAD – I know it sounds nutty with echoes with that apocryphal story of primitive people thinking that photography stole one’s soul – but it seems like the more images we make of ourselves the more insubstantial we feel.

PU – Yes! And especially the pictures we post of themselves online. There we’re atomized into millions of immaterial representations. Pictures that were intended to say ‘I am here’ become part of this collective online archive and do just the opposite – they become a part of an anonymous sea of millions of people that are everywhere and really nowhere at all. And that is the life of a ghost, a total purgatory, or limbo that is neither heaven nor hell, just floating around in this insubstantial in-between.

MAD – What we are talking about reminds me a little of Hans Peter Feldmann who I just wrote about for Aperture. He has been working with pre-existing images for 40 years and he occasionally makes his own images but he makes no distinction between photographs he makes himself or those that he collects. He does not believe in the redemptive image – he gathers images of a type and what happens is a kind of flattening out….

PU – This goes back to the idea of narrative in a way, that flattening out which then questions the narrative integrity of the singular image. But what happens is it forces a narrative contingency between the images, and I think that’s true with my work, Feldmann’s work and, for example, Warhol’s work, not that I would compare myself to Warhol or Feldmann…

MAD – No, I think that’s a fair comparison…….

PU – Well part of our idea of multiplicity and repetition comes from Warhol. I think the ‘death of the author’ idea is at work there but I think it goes deeper than that which is a kind of profound understanding that we ourselves are repeated forms, that we are 99.9% genetically the same as everyone else, and that in some ways we are completely anonymous in an overpopulated world. In a way I agree with Feldmann’s skepticism about the transcendent or redemptive promise of art, although sometimes when I am deeply involved with my own process I can get lost and forget myself and I guess that is a kind of transcendence. But I am not sure my work is redemptive or transcendent for anyone else. And at times its just really hard and repetitive work – like when I realize I have to find a thousand more images of the TVs being sold on Craigslist pictured in profile in order to make an installation I am doing work.

MAD – I do think that the notion of the transcendent or redemptive power of art has been overblown with maybe centuries of hyperbolic rhetoric from art historians, critics, and artists themselves, so perhaps it has become an impossible expectation. But clearly humans desire to express themselves esthetically and there are lots of reasons people go to museums or galleries but one of them is to see something they have never seen before, to refresh or challenge their perceptions on some level.

PU – Do you think that might also apply to news media? Would shocking news images fall under that idea of challenging one’s perceptions or into the category of transcendence?

MAD – I don’t know. In the immediate aftermath of the Japanese earthquake and tsunami there were all of these videos online of the rising waters. I know how ethically suspect this sounds but I had a powerful esthetic experience – I felt overwhelming terror and a sense of wonder at the unstoppable force of it even as I am watched on my laptop.

But back to your work – one of the things that you do is to recontextualize pretty banal imagery and transform it into something else. There is no expectation of a contemplative experience if you think about those mirrors in their original context. You take this thing which is really just a minor detail, a decorative element in a stock image that is intended to sell furniture and you go inside that image, excerpt this minor detail, and transform it into a meditation on erasure and insubstantiality. That to me is fucking magic, that is the alchemical aspect of art.

PU – I get the alchemical reaction you are talking about but I think about how that image is manipulated, how the people designing those interiors are trying to make me feel certain things. Back to the idea of narrative again, I often play off of a conceived fiction as I am making the work. With the mirror project, I played with the idea that we were intended to vicariously wander through those spaces, those idealized rooms. I wondered who were the people that lived there and who would I see if I looked in the mirror. Coincidentally, and on a more personal level, when I was beginning the work on the mirror images, my own bathroom mirror broke and I neglected to replace it for some time. It was on odd experience you stand at the sink and throw water on your face, wipe yourself dry with a towel and then look up. You expect to see your reflection looking back at you but you’re not there. So the result of this domestic laziness began to inform the work for me – in a sense it was this visceral experience that drove the work.