Mark Street

I sometimes wonder if there is any relation between the name we are given at birth and the lives we lead. Probably not for most of us, but there are people whose names somehow encapsulate an ethos, behavior, or passion of a life, and Mark Street’s name does just that. He makes films whose range of subjects is extraordinarily diverse. Although there is no single theme that connects his eclectic body of work; the image of the city, as site, as home, as a place of alienation, of cultural collage, and finally of fascination, runs through both his shorter experimental works and his feature length narratives. His home city of New York plays a central role in films such as Fulton Fish Market and Rockaway. And far flung cities such as San Francisco, Baltimore, Buenas Aires, Montevideo, Dakar, Hanoi, and Marseille, are not simply picturesque backdrops but are vividly rendered in film such as At Home and Asea, Hidden in Plain Sight and Hasta Nunca. To put too fine a point on it, his films mark the street. He is a roamer, a modern day flaneur stalking alleyways and avenues with his camera reminiscent more of a mid-twentieth century photographer in the model of Andre Kertesz, Henri Cartier-Bresson or Robert Frank than heir to the experimental film ethos of Stan Brakhage.

Mark is my friend and one of the benefits of this friendship is that I can sometimes see a film in progress. When he returned from shooting his new feature Hasta Nunca in Montevideo last summer, he showed me some of the unedited footage. I was entranced by city itself, its raw beauty, and its faded elegance, its vivid street life. The pace of the footage, the slow reveal, if you will, transported me to a metropolitan world that was both familiar and utterly mysterious. Later when I previewed an edited version, when the characters and narrative were in place, none of that enigmatic atmosphere had dissipated. With this new film I think Mark Street has done something quietly miraculous. He has imagined a world where character and place are inextricably entwined, in which the protagonist is both in love with and estranged from his city. The filmmaker’s unorthodox dance between long and short form, between character driven narrative and formal experimentation has found a peaceful co-existence in Hasta Nunca.

This conversation took place in Mark’s Brooklyn backyard, April 2012.

MAD: So I was wondering, if was there some film, the ‘Ur’ film that you saw that sort of knocked you out, produced a moment of recognition – like that’s something you need to investigate or follow?

MS: It was really being at Bard College and seeing these personal expressions in film. I remember seeing Warhol films and Marie Menken’s Notebooks. It wasn’t one particular film that inspired me but an aggregate of personal cinema.

MAD: Did you go to Bard to study film or was it you took a class in experimental film and that’s where the revelation happened?

MS: Well experimental film was the spoken language there, it was what they taught. I knew I wanted to make films, but there was a big gap between films I loved and how I imagined being involved. I remember having reviewed Apocalypse Now for my high school newspaper. And I loved it, but I couldn’t see the human agency in it. It didn’t seem like one person’s voice or one person’s vision. When I got to Bard it was all about these personal effusions, and I started to make the connections between things I was doing with photography and pimply teenage prose I was writing and filmmaking. I thought, “OK, so this is one person’s voice, not a machine.” I continue to be animated by this belief in the personal voice in filmmaking.

MAD: Now you make short ‘experimental films’ and you make longer narrative films, feature length films. And in some ways seem to go back and forth. Is there a reason for that? What does that do for you?

MS: Well I just I’ve never felt contained by either world. I started off in the experimental world, but I had some things to say or had some interests that were outside the avant-garde orthodoxy, if you want to look at it that way. And when I first moved to New York, I spent a lot of time going to see independent features at places like Film Forum and I just felt like there was a kind of mode of narrative expression that I couldn’t do in shorter more aesthetically charged films. Isort of bounce back and forth between those worlds. Sometimes I feel like I’m looking for love in both of those places, you know? And I’m at once soothed and irritated by both of the worlds.

Stan Brakhage once looked at a film of mine, I think it was Guiding Fictions, and he left me a long message on my answering machine. It was very sweet and generous and laudatory but when I heard that message, it really crushed me because It made me feel like I could not fulfill or live up to those expectations and it made me want to do things like make a longer narrative film. Reminds me of a story you tell and I’m only comparing myself to Diane Arbus in this very narrow sense, … she was a painter and a teacher says, oh you’re so brilliant, you’re so great and it just irritated her. And she wanted to do something that she was not ostensibly great at. I’m not saying that I was great at filmmaking…

MAD: Yeah she was very uncomfortable with this sort of laudatory observation. She didn’t want to be so good; I think she craved a kind of discomfort.

MS: Exactly. So I’m not saying I’ve received that many laudatory things, but…

MAD: But from Stan Brakhage, I mean that’s like getting praise from the dad, right?

MS: I had a sort of Oedipal reaction, like, I don’t want this. He was completely generous and poetic … it’s not about him what I’m talking about is my inability to deal with it and my desire to be somewhere where I wasn’t wanted. As soon as I’m wanted I want to flee!

MS: I know you have your own personal reasons for making these two kinds of films – the short experimental form and the feature length narrative – but are the audiences that different?

MS: Oh yeah, I think they are completely different worlds, really. I mean when I send out a feature film like Hasta Nunca I feel like all the other films I’ve made are not even relevant.

MAD: Is that true? Does it happen in the opposite direction people you know from the experimental world are like what are you doing with these long narrative films?

MS: Here’s a story about something that didn’t happen to me, but I feel like it did. A friend of mine from Bard started to work in the longer form later on and one of our former professors said, ‘I hear you’ve gone narrative’, It’s like saying I hear you’ve…

MAD: Gone to the other side.

MS: Gone to the other side. And I think part of is that the avant-garde, experimental film world is defined by the alternative, or by what it’s not. The experimental / avant-garde approach is described in the negative – “It’s not narrative, or linear, or it’s not 90 minutes long, It’s not character driven or a host of other descriptives”. And then you start to say “well my new film is 90 minutes long and has elements of narrative and character” and people roll their eyes. I did a show at Binghamton last October and I showed these experimental films and there was a lot of discussion. Then I was going to show a part of Rockaway one of my features, and I just I literally could not do it.

MAD: It would not have been received well? It would’ve just changed the discussion in such a way, so radically that…

MS: I felt the S&M of the avant-garde, the professors are there, wanting everybody to make films like Marie Menken’s, forcing an agenda. And the students are there wanting to make features. So there’s this tension in the room immediately and I was kind of in the middle. And I gave the professors what they wanted and alienated the students. I just felt uncomfortable about putting the feature up there, alienating everybody. It felt like by the end of the night, there’s going to be no one on my side.

MAD: Haha. You’re a half-traitor to everyone.

MS: Exactly, half traitor to my class in that sense.

MAD: You get to these kind of issues in your essay Film is Dead Long Live Film, which you start with a startling observation, “I feel like I’ve been waiting for film to die my entire adult life” and you go on to say, “film is no longer the detritus of the culture and using it is no longer considered reaction against planned obsolescence. Film is the old grandfather in the corner, who’s demented and senile and repeats himself over and over again. It’s not underground, hip, indie or pure. It’s expensive and all but dead.” I just love that, it’s so vivid! Something else struck me from your essay. Although you don’t despair at the loss of film in the digital age, per se, you do describe the depth of the screen on which an analog film is being projected as if one could step into it or sink into it and I was sort of struck by that. And I was wondering, I know you try hard not to be nostalgic around the changing of media and that kind of thing, but at the same time there’s a moment in that essay where you talk about the depth of the screen and observing this film and you say, that you could almost sort of step into it or fall into it, into the depth of that screen. I’m wondering do you think that, that experience is something that the contemporary audience is kind of blind to or just insensitive to or just don’t experience and does it matter?

MS: Well that’s a great question. I try hard to not to be nostalgic, but I am sometimes. I went to see Jeanne Dielman, the Chantal Akerman film, maybe a year ago and honestly I had never understood that film on VHS,it’s a totally different thing, the space, sinking into the screen and the spatial relations and all that. Ithink that digital projection is pretty good these days, but I wonder if what people are missing is this sort of shared experience in the theater. Students are popping in DVDs and looking at stuff on Youtube and I wonder if that kind of relation to the screen or relation to the project as object is completely gone.

MAD: I think it’s true. I mean, not only, I mean so thing are, viewing habits are changing so they’re less communal. There are still communal experiences obviously, but it’s less essential now, this idea of people being in a space where it’s unique, that experience of a large image, projected image and light passing through film, that kind of spatial or depth that that can create. And again, this pool of light, to continue that metaphor, all of these individuals dipping into this pool together, right? I mean obviously digital projection is clean and bright and crisp and all these things, but it’s not, it doesn’t have the same sense of falling into or this kind of other space.

MS: Yeah. Similar to something else you said years ago, at the level of politics, activism is now all signing onto some sort of PDF.

MAD: Online petition.

MS: Online petition or something that used to be more about walking in the streets, you’re putting yourself there and saying I’m going to be there and it’s true culturally, you go to a theater and you’re there and you are having this shared experience with other people. You’re expending your cultural capital in public and I think more and more it’s about seeing things in your own living room, surrounded by your own possessions and not taking the risk out in the world

MAD: It’s like everyone gets the references or knows the references, but they don’t have the experience of? That’s a different kind of thing?

MS: I think it is, yeah.

MAD: But, so at the end of your essay, you make a turn, I think, in that you say that you contradict the title of the essay when you say that you no longer shrug off the demise of film. I mean, we are addressing that already. So it’s like a kind of eulogy in a kind of sense, right? I guess with the title, “Film is Dead Long Live Film”, it would be a eulogy. So you brush the dirt from your hands and you walk away from the funeral. Speaking of burials, I wanted to ask you about a short film you made – Vera Drake Buried is it?

MS: Vera Drake Drowning.

MAD: That’s the one that you buried, right?

MS: Right.

MAD: And then you unearthed it.

MS: I did.

MAD: So you resurrected it and it’s kind of like sort of like a zombie film now, right? Like its decaying flesh is falling off and the burial itself was very ritualistic. Obviously you wanted to see what would happen to change the film through the uncontrollable forces of moisture, cold, dirt, insects etc, but at the same time it’s also very ritualistic, to bury it and then to unearth it.

MS: I found that trailer for the Mike Leigh film Vera Drake in the trash behind the theater on Court Street and then I buried it right out here in this yard. I think it was a couple seasons, a couple winters. It felt like this kind of performance piece or reclaiming it or something like that.

MAD: You have another essay that I like very much called “Festival of Flights”. And I think you use this term ‘distant social relations’. And I thought that this phrase related to a lot of your work, in particular the films Hidden in Plain Sight and Hasta Nunca, in different ways. So I thought we’d talk about Hidden in Plain Sight first.

MS: Sure.

MAD: The title itself made me question, what is hidden, or who is hidden in the film? That was an ongoing question as I was watching, like ‘what am I looking at, what am I missing? Obviously it happens on a multiple levels, but there’s definitely a kind of heightened sense of self-consciousness, especially in a film that in some ways is about being a stranger in a strange land, which is then exacerbated by the camera. You’re not just the kind of silent observer; you’re a kind of active observer with a device. And there’s a sense of stalking your subjects. You stalk them in the street, approach from behind or observe them from a window or a doorway and sometimes the observer, the observed returns the gaze and you cut the scene at that moment of reciprocal watching almost as if you had been found out. So to me, it was really part of the on-going reflexivity of the film, which is like, oh you’re hidden in plain sight too, right, as the observer. And I was really thinking about you as a photographer in that film. You know, I think that you start the film with a series of stills pretty much and then you end the film with a series of stills, isn’t that true?

MS: Yeah.

MAD: Yeah and I love the way you set up stationary tableaux through which these varied citizens of the world pass. It’s the poetry of the everyday…

MS: Well, that was conscious. I really have always felt like a photographer with a movie camera. In terms of sensibility, I remember when I used to shoot with a Bolex, I felt like the hundred-foot spool of film was akin to the 36 exposures, the roll of 35mm film that I grew up with. Now of course it’s digital, it’s a different world, but I’m at ease with that boundary. You know, a hundred feet of film, 36 exposures, that kind of marking of an experience. An afternoon walk, a hundred feet of film or whatever. I’ve talked to people and they’ve said, “Whatyou’re just going out onto the street and shoot?” And to me that seems perfectly reasonable, but I think it’s more of a still photographer’s sensibility than it is a filmmaker’s sensibility. It’s like fishing, you know, standing in a corner and fishing. That’s pretty mainstream for a photographer, I saw Bill Cunningham on the street the other day just standing there with his camera watching what was going by. So it’s perfectly accepted for a photographer to work that way as an inspiration, but not so much for filmmakers in the larger sense. So I always have felt more akin to photographers in that way. If I am at a party or something, if someone says, oh this guy’s a filmmaker, you should really talk to him or this woman’s a photographer or an artist, I would much rather talk to the photographer, the painter, than the filmmaker.

MAD: Because you have more in common in some ways.

MS: Yeah, I just don’t feel like I’m a filmmaker in the traditional sense in terms of pre-production and post-production.

MAD: I thought Hidden in Plain Sight is so much about photography, in so many ways. And you have these sort of interstitial quotes sometimes. I think some of them are your quotes and some of them are people like the Polish journalist Ryzard Kapucinski and Homi Bhabha.

MS: Yeah, literature.

MAD: And you have this phrase, “I keep barricading myself in cafes, bars and restaurants” – I’m wondering about that observation and does that have anything to do with the dilemma at the heart of film and photography, which is that representing others, especially foreign others, can be a kind of form of colonialism or exploitation in that there’s a kind of sense of guilt or ethical dilemma, yet we feel compelled to do it nevertheless.

MS: I think that’s the heart of that film really. I wanted to harken back to a time where you could go for a walk with a camera and take in what you took. I mean, I looked at the City Symphony films of the 1930s and thought a lot about the issues of the flaneur armed with a camera.

MAD: Right.

MS: But I had been trained in such a way, with Trin Min Ha and you know the cultural politics of the 1970s, to think in a larger way about things and to feel some sort of instinctive reaction to that kind of colonialism of the camera. I wanted to have it both ways. I wanted to go out and shoot and then I wanted to question it and I wanted to bring in my own doubts and my own discomfort in as well. I wanted to give voice to both the sensibilities. The ostensible freedom and I guess its privilege of shooting and then reflection, I’ve seen a lot ofhand wringing films about the impossibility of capturing anything and so they’re not really, they’re not really films, they’re more about the idea about not being able to make a film!

MAD: Right. I think that a rigorous interrogation of the medium of representation in general is really important. Over the last generation or so we have seen it in photography, in literature, and anthropology. But for some, the investigation stops there – as if to imply, ‘okay now I’ve apologized and I’ve had enough of feeling guilty’ so I think I will just turn the camera inward. The result of which can be the world recedes as the solipsism grows. I think to represent is to risk on some level. But, to not do so in service of some kind of like political safety seems to do a disservice to art and culture. It seems cowardly or unimaginative.

MS: It’s sort of self-censorious too and narcissistic in it’s own way, as if you’ve embodied the critique before the audience can even react.

MAD: Yeah, who cares? That’s so boring first of all.

MS: Hidden in Plain Sight was an attempt to get out of that quagmire. I was looking for… A giddiness, Courage! Giddy courage. With that film, I really took it to extremes; I went to Dakar in Senegal by myself just to film for no other reason except to film. I realized that gesture was wrought with all sorts of entanglements in terms of the colonial gaze and things like that, but I thought I just do it and later on pick up the pieces and hopefully interject it with some of this kind of dialogue we’re talking about. So it was an attempt to break free and find solace in the initial impulse. And I think that’s being an artist in some ways…saying, “I’m just going to do this thing”. And when you go see work, you can feel the germ of someone’s initial… why can’t I think of the word? Conceit! You know, I’m just going to go do it, why the fuck not? I think I got that from the experimental world. And I think I tried to bring it into the narrative world and what’s confused me is sometimes I feel like there’s a kind of courage that comes from the experimental world, that gets mixed up with a bit of orthodoxy. I try to take that privilege that comes from the experimental world and enact it in the narrative world. I mean when I did with my first narrative feature At Home and Asea, I thought, why the hell not? Why shouldn’t I make a longer film? Why shouldn’t I work with actors? Never done this before, why the hell not?

MAD: Certain bravado and audacity. A couple of other things about Hidden in Plain Sight. You say in the film “I try to embrace the microcosmic”. And then we see a series of details; in fact, you title them like, ‘outside barber shop’ or “phone numbers on walls.” This idea echoes Walter Benjamin, this accumulation of details, an archive of small gestures, which lead to a kind of history. And I’m thinking in particular of a single street corner in Dakar where there’s like a tree and a sign post which sort of act as anchors, framing devices, while a river of humanity kind of goes by, streaming by. But just this idea of allowing the world to pass through your frame and allow, in some ways the material to kind of speak for itself and represent itself on some level. I really love that about that film.

MS: I went to these places that I didn’t know too much about like Hanoi, Dakar, Santiago Chile, Marseille, and I would just sort of pick a spot in the flux of life there and just hold my ground and as you say, let the visual world flow around me. I think a lot of that sort of macrocosmic vision was defensive, I was so overloaded visually and culturally all I could do was just LOOK, wide eyed, as it were, at what was right in front of me.

MAD: You have the cities as African city and Asian city, South-American city, European city, and then there’s New York, of course, so was that very deliberate?

MS: The initial idea was one, you know, one city per continent. But Australia, really, who gives a fuck?

MAD: Haha. Your new film Hasta Nunca was shot in Montevideo Uruguay, I want to know why there? It’s such a beautiful film on so many levels. The opening scene is as I recall, a morning scene? And there is this bright luminescence on a building on the background, which just seems golden and in the foreground it’s kind of early morning grey. It’s interesting how the film opens with an image that is like a mirage. The city is this kind of Illusion or layered with simultaneous realities. I just love that… So why Montevideo?

MS: Well I sort of stumbled on the city. I was in Buenos Aires, then on a lark took the ferry over to Montevideo where I taught some workshops with {my wife} Lynne Sachs at an artist’s collective there. I just love that city visually. I just felt like it had this sort of ungentrified, untamed beauty. And there’s this sort of detritus culture, collaged and layered. It’s a big flea market city, so you get this sort of mixed and matched sensibility. It’s like a bit like Oakland to Buenos Aires’s San Francisco, it’s grittier and tougher and no one has bothered to paper over it’s colonial past. There are vestiges of Portuguese, English, and Spanish elements, and culture from Brazil coming down making it a little bit more diverse. And Italianate culture, from its more recent immigration waves. So I just thought it was a really special place, visually, and I remember walking down the street and thinking, I could come down here and make a film. The location is the character and I felt that way about Rockaway and about At Home and Asea as well. It started with the kind of shot you’re describing in Hidden in Plain Sight, a kind of establishing shot and then the narrative and the character things came later.

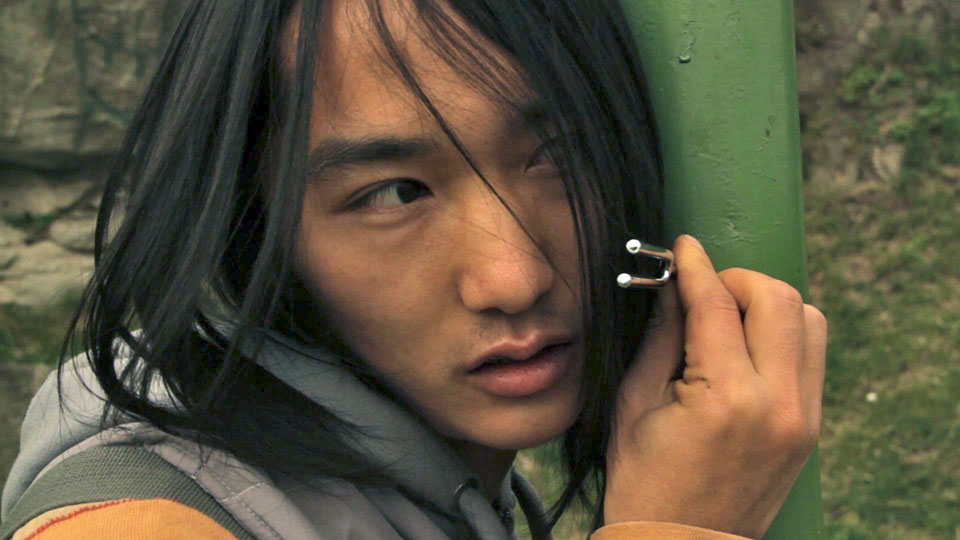

MAD: So you have a central character in Hasta Nunca, Mario. And he’s this sort of eccentric radio announcer for a program called Secrets and Stories or Stories and Secrets? He speaks into a microphone in a small studio and ostensibly he’s speaking to this broad audience, his voice is going out over the city and people tune their radios to hear this disembodied voice. And he speaks conversationally about the Situationists and ideas like the concept of drift and navigating the city and I felt in a way like Mario was similar to some of the ways you’ve described yourself in terms of being an artist. In your writing you sort of you speak in this voice that balances enthusiasm and cynicism about your own contributions and what you call a hubris of being an artist and I feel like Mario, in Hasta Nunca, is in a way connected to this contradiction. You know, like he’s caring, he wants to reach out, he wants to communicate, he speaks with empathy for the individual and for the general human condition, but in some ways he’s undermined by his own alienation from his personal life, you know? And I don’t know, I just felt like he was a really, without it being over-determined, a beautifully drawn character.

MS: Well that’s great. I’m glad to acknowledge those autobiographical connections; one of the things is his investment in spontaneity, he just does sort of does everything off the cuff, in the moment and he knows it’s not perfect but he believes in it as a way of life. That’s his ethos. And that’s my style of directing too. I have impatience, a very deep impatience that as you know, is gift and a detriment. But if I’m around a crew of people and we are filming, I think, let’s do this and get out of here and let me go back to setting up a camera on the street and shooting by myself. I’m happy to work with people, but I really I don’t love it. I think that Mario’s like that, he likes the idea of people and he likes a limited contact, but he’s ultimately by himself.

MAD: But it’s episodic. Like he walks down the street and people are like, ‘Hey Mario!’ And he goes over there and he talks to them, he indulges these brief encounters and then keeps going, keeps moving.

MS: Exactly. I think him walking down the street and brushing up against people and also maintaining his persona is something that I do. The camera for me, or the apparatus of cinema, is not a way of creating community. It is for some people. To me it’s like, let’s get this done and let me go back, honestly, let me go back to shooting on the street solo!

MAD: Radio plays a central character in the film. There’s this kind of romantic quality to that, right? A medium of another era. It’s not that people don’t have cell phones in your film, but people aren’t texting or on their phones or iPods all the time. It’s more this anachronistic idea of a disembodied voice floating over the airwaves connecting to distinct individuals spread out all over the city. You know, there’s something romantic in that. It’s very early 20th century in a sense.

MS: It is and I struggle with that cause I didn’t want paint Montevideo as this backwards place where people are around their transistor radios. I spoke with Uzi Sabah the producer of the film, who grew up in Uruguay he said radio is big there. I mean, it may be on computers, but it’s a site where people are connected.

MAD: I didn’t feel like the film was nostalgic in anyway. It felt very contemporary. I just liked that there were these other motifs that seemed connected to the past. I think you have a quote in Hidden in Plain Sight that states: “All cities are geological. You cannot take three steps without encountering ghosts bearing all prestige of their legends.” And I thought that that was embodied in Hasta Nunca that history emanates from the architecture, the air, the graffiti that seems to cover everything, that there are multiple voices, ghosts who won’t go away. I didn’t feel it was nostalgic, it felt very contemporary yet deeply cognizant of the past…. deep.

MS: That’s great, that’s one of the things that I loved about Montevideo. The graffiti, particularly. Graffiti is in almost every shot, and I just tried to find locations that gave voice to these sort of spectral presences that you’re talking about.

MAD: In some conventional sense nothing happens in the film, right? Although we have this fully developed character that we see regularly and he is charming and deeply immersed in his world. Towards the end of the film there is a hint that there might be a trajectory toward a kind of romance. The main character Mario and this woman cross paths and spend time together moving through the city: exploring flea markets, watching daybreak by the water. Just in terms of my narrative expectations, I think okay, now something’s going to happen, something’s going to begin. Up to this point the film has been full of atmosphere and gesture, but when something begins to happen, at least in conventional narrative terms, your character, Mario rejects it.

MS: Exactly, but I mean he turns away from that moment, right, then he goes off on his own and then he seems to leave behind the radio and towards a more pure expression. But it’s an interesting moment, where you bring the viewer there and then, again, a conventional narrative would have them hook up or have some kind of reason for being together or breaking apart, but in fact it remains mysterious.

I mean, some of that is my failing, which I completely embrace. I just couldn’t pull it off denouementis not in me, you know. Or I thought directing in the traditional sense is not in me. So people talked about putting them in bed together and I shrank from that direct of a human connection. I didn’t want the character to have it, just as I was afraid of having it myself, emotionally, as a director. I’m much more distant, removed. So he kind of flirts around with her and has a night and drinks and by the morning he’s ready to be by himself. That’s a real, that’s a real emotion too. Flight is a choice too! That’s a familiar emotional denouement for me. Those kinds of ripples of contradiction I find very interesting. It’s almost like a Holden Caulfield thing when he’s sitting on the bed with a prostitute and doesn’t sleep with her. We sort of want him to sleep with her, but he’s thinking something else. I thought wouldn’t it be great if there were this younger woman and middle-aged man, but the man’s too divided against himself jump in. I originally conceived of it as an ANTI-midlife crisis film: a man who thinks he wants freedom but is too internally conflicted to follow through. He’s too alienated even from himself to do it. So anyway, that’s where it came from.

MAD: I didn’t feel like it was a failure of the filmmaker when I was watching, I thought it seemed, it surprised me. I like the way it toyed with my, you know, narrative expectations. And I felt you know really satisfied with that. I just felt like it was honest and not gratuitous in any way. I thought it was true to his character.

MS: We really struggled with that in editing and had to get it right because it was so unexpected I guess. We had to finesse it just right. As it stands now, which is pretty much the end, the world kind of closes in on him and his public persona stultifies him.

MAD: I was so immersed in that world, in that character. I knew there were levels of improvisation, but it didn’t feel loose or ragged. It felt open and airy, like the wind was ruffling the narrative this way and that way, but it always felt intrinsic to the atmosphere of that place.

MS: That’s wonderful.

MAD: It has to do with the talent of the people you’re working with, but also, you’re ability to find a kind of balance between structure and openness.

MS: People have different ways of preparing. I hate to write screenplays and think of narrative things. What I do is I go out and film, film street scenes, like a bunch of interstitial tableaux, or establishing shots. In preparation I would walk around with a flip camera thinking, oh, this corner, yes, if I could capture this corner narratively, that would work and like what you’re saying about the wind flowing through or the light hitting an object or something. That’s my real inspiration. It’s not narrative events, it never has been. Sometimes when my students show me their films I can’t even see the story! I’m focused on what’s going on in the background, the strange playful abstractions of light or some other obscure detail.