Lori Nix

From its inception to current practices, photography has been fundamentally linked to the diorama. In 1823, before he became preoccupied with refining Niepce’s process on his way to patenting the Daguerreotype, Louis Daguerre invented the diorama as a spectacle for education and entertainment. From David Levinthal’s miniature tableaux using children’s toys to Tim Burton’s stop-motion animation, small-scale replicas of the realistic and fantastic, are prevalent in popular culture and art.

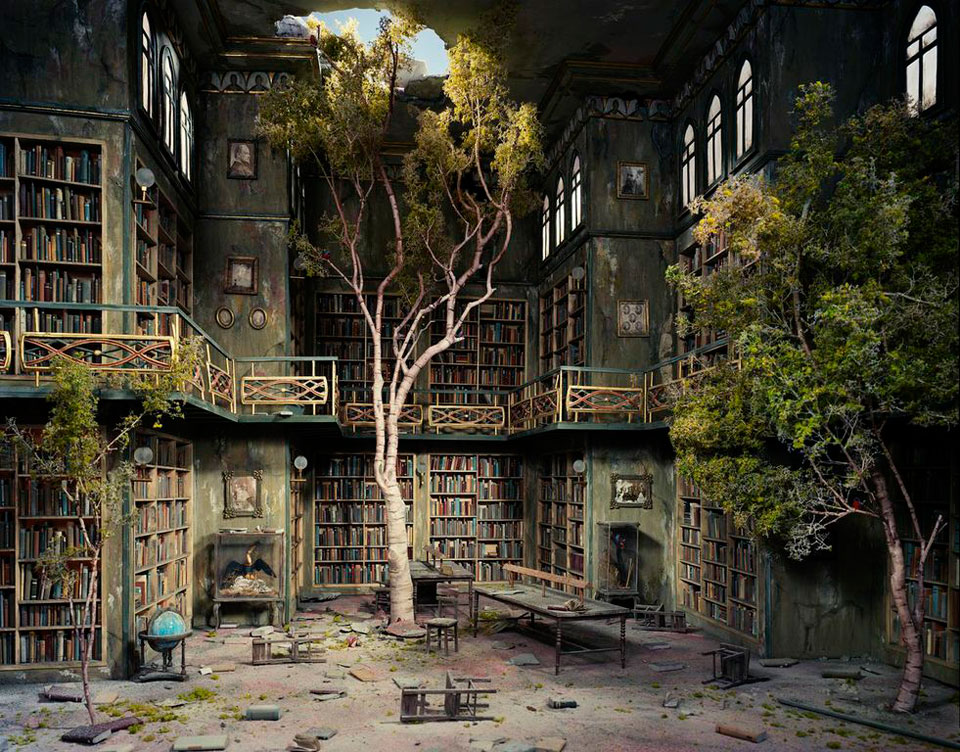

All studio photographers play God on some level, separating light from dark, shaping primal materials to create new worlds that are sometimes inhabited sometimes lifeless. According to the Judeo/Christian tradition, God rested on the seventh day. I don’t think Lori Nix ever rests. Her life appears to be wholly (and happily) consumed in the planning, construction and photographing elaborate miniatures. Despite the ominous themes of her work, Lori is funny, charming and unpretentious. We chatted for quite a while in front of a newly completed diorama depicting a decaying Air and Space Museum. Like a postcard sent from the other side of the Apocalypse, the longer I looked the more the fantastic details were revealed. It made me want to visit.

This interview took place in April, 2013 in her studio / home where she lives and works, with her partner and collaborator Kathleen Gerber across the street from Prospect Park in Brooklyn

MAD – This has been your home and studio for 13 years. Where were you working and living before this?

LN – Columbus Ohio, I went to graduate school in Athens Ohio and moved to the big city of Columbus in search of a job. I went to work at a color lab, which is what I am trained to do, to print.

MAD – What precipitated moving to NYC?

LN – Two photo labs I worked at went out of business, and it’s the only thing I know, I needed a job, so I thought “Lets move to the center of the photo universe.” I am still at a photo lab (Laughter).

MAD – Whatever it takes, right?

LN – It helps me produce my work

MAD – Were you making and photographing dioramas in grad school?

LN – No actually I was working in room-size installations. Sort of Cindy Sherman-esque in which I was dressing up as characters.

MAD –Are those now hidden away somewhere or have you shown them, do you use them as a part of the history of your work?

LN – They were probably on a website at some point and I’m hoping that website is long gone. I’m not embarrassed by the work, but in grad school one is expected to make work on some significant topic or theme. My professor at the time taught by the mantra that ‘the personal is the political’, so he was really pushing people to do political work. It was also that ascendant moment of identity politics so I dressed myself up as characters that I never wanted to be like a young Jewish intellectual or a Southern Belle.

MAD – They sound funny. There is still humor in your work, even if you are picturing post-apocalyptic scenarios.

LN – I hope so, I have to laugh, I don’t take too many things seriously.

MAD – Did moving to NYC change your work? Having less space and that kind of thing?

LN – No, I was just finishing up the Accidentally Kansas series which are small tabletop dioramas and when I moved to Brooklyn in 1999 I actually had more space than in Columbus. But it changed my work because I was changing, I was no longer in the comfortable mid-west, so things were a little more edgy. And then Kathleen came on board to help build the dioramas. She is trained in glass casting and has a decorative arts background.

MAD – I first saw your work in Lightwork’s publication Contact Sheet – these were the images from Accidentally Kansas and the next series Some Other Place. I was immediately drawn to them and have been showing them to my students ever since. When I look at the ‘Ice Storm’ image I couldn’t help but think of the Russell Banks novel ‘The Sweet Hereafter’ and the film that Atom Egoyan made based on it. Do you know it? Were you referencing it? It’s a quiet tragic story about a school bus full of kids that goes plunging into an icy pond and what happens to the town and families after this horrible accident. I know it sounds grim, but it’s an incredibly subtle and sensitive story.

LN – Every one of those images in Accidentally Kansas has a personal story attached to it. It doesn’t matter if you know that story but it helped me imagine the scenarios. But for that particular image I picture my family when I was growing up. We are all in our station wagon, my brother and I are fighting in the back seat and my dad is driving but is turned around trying to get us to stop. He swerves to miss the deer on the icy road and off my family goes to their icy death. That would be the Nix family way to go, still fighting all the way down. Nixes are nixed. What a funny tragedy right?

MAD- Its so strange to look at these everyday disasters, tornadoes, plane crashes, toxic spills, cars abandoned in blizzards, and not be charmed by the soft focus and diminutive scale. In some sense they represent a kind of talismanic wish that such things might be avoided if we can imagine them fully and control them. Is that part of it, or is it that your imagination just naturally is drawn towards that kind of end point?

LN – My imagination definitely goes toward the end point. I already have the whole end of the world figured out! (Laughter). It’s easy to say sitting here but I am not afraid, I see it as another adventure. When I was growing up in western Kansas every season had a new disaster. I have been in floods, tornados, blizzards, and when you are kid, your parents are there to deal with the stress but for me it was such an adventure, my boring life became suddenly exciting. A tornado ripped through our neighborhood in Topeka, three houses down there was nothing left standing. A couple of days later I was playing in the woods seeing all of the scattered debris, I came upon a stove and when I opened the oven door there was a perfect golden ham, the tornado hit right at dinner time.

MAD – How old were you?

LN – I was probably 11 or 12.

MAD – It’s such a vivid image. There’s the chaotic power of the tornado but its also about extreme displacement, surprise, horror and humor in the same moment.

LN – Yes but to a kid it’s all adventure.

MAD – You refer to the desire for the sublime – I think of the sublime as a phenomenon of the 16-19th centuries –because of exploration of new continents Europeans were seeing the world as bigger and stranger than they had ever imagined – hence the terrible wonder. Where do you think the sublime is now? Is that what we have art for?

LN – I’m not making art with a capital A, I don’t have grandiose ideas about what I am doing. When we are building the dioramas and photographing them, our view is pretty limited to the myriad details of making it look good.

MAD – You describe yourself as a faux-landscape photographer, and you connect yourself esthetically to the Hudson River School painters like Thomas Cole, but do you consider yourself a part of a photographic lineage of landscape photographers in any way? Watkins, Adams, Misrach, whose work discovers and describes landscapes through photography?

LN – No not really, I don’t really spend that much time outside, I am always here in the studio working. I’ve traveled very little. I travel through television or the Internet and try to imagine places. To go back to the sublime, I think it will happen through the exploration of outer space. There’s got to be stuff out there that we cannot wrap our heads around.

MAD – I agree, I think that is why the Hubble has proved to be so popular, it has brought us images that have challenged our visual understanding of the universe. The Deep Field images for example, when they chose a tiny and relatively empty part of the sky and looked deep into space and therefore deep into the past and they found thick clusters of early galaxies sparking up the early universe not long after the Big Bang.

MAD – You don’t do any digital retouching in your work.

LN – No, I don’t. It’s all about the negative. I have been printing the images directly from the negative. But lately I have been having some problems with my eyes and I am going to start scanning the negatives to make ink jet prints. I still like the big real estate of an 8×10 negative and besides I cannot afford or justify the cost of a digital back when I make about 3 images a year. As long as Kodak makes film, I will be shooting with it. But even with scanning the negatives, I am not interested in retouching. We like to leave in all of our mistakes.

MAD – Since your sets depend on accuracy of detail, texture, lighting, scale, and surface – is the lack of human representations a matter of the impossibility of creating convincing human figures? Or is it just in the imagining of a post-human landscape?

LN – My first concern is that having small-scale humans in the image makes it look more like a model, those small human figures are not convincing and it would date the work. Secondly, I am just not that interested in humans; I am interested in plants, animals and architecture. The photographs I have always been drawn to have been landscape and architectural and not portraiture, although my next body of work will have people in it.

MAD – Real people?

LN – Representations of people, right Kathleen?

KG – We’ll see how it goes. (Laughter)

MAD – The diorama is a primary vehicle for presenting moments in history in perpetuity. It is a three-dimensional world but with perspective, framing and viewpoint controlled by a plate glass window.

LN – Yes, we make the dioramas to be seen by the camera from one particular viewpoint. When I showed the actual dioramas at the Museum of Art and Design, I told the curator that I was not interested in finishing them off so they looked good from 360 degrees. You could see the pink foam and the hot glue but that is how we work.

MAD – But isn’t that part of the revelation? I know you don’t want to get into a compare and contrast situation, as the photograph is the primary vehicle for your ideas, but seeing the incompleteness of the model and the humble materials with which it is made says so much about the transformative power of photography.

LN – What was fun at the Museum of Art and Design was watching people photographing my models with their cell phones, trying, I assume, to get the same results.

MAD – Are you concerned that the work might be nostalgic? I was thinking that some of your constructed spaces – like the library, the map room, the Laundromat and the beauty parlor are from an earlier era – as if these spaces are already if not in literal ruin, than metaphoric ruin.

LN – I am trying to make beautiful pictures that have enough resonance to remain in memory and maybe hint at the violence that lies outside the frame. I guess anything having to do with the past, even if it’s a future past, has some element of nostalgia.

MAD – Do you feel bad about destroying a diorama after you are done with it, considering it can take months to build?

LN – Not one bit. To me the photograph is the final thing; I don’t care about the stuff after it’s done. I work really hard to make things look good, but it’s not going to have a second life.

MAD – Kathleen, do you ever feel reluctant to destroy what you’ve worked so hard on for months?

KG – I like to save some of the little pieces if I think we might be able to use them again but otherwise I am so ready for it to be gone. Having to live with it day and night for months you get over any romance you might have. Sometimes there is barely enough room to open the refrigerator with the tools and the parts strewn all over the house.

LN – We have dinner with the dioramas, we watch TV with the dioramas….