Karen Yasinsky

Karen Yasinsky is an artist working primarily with animation and drawing. Materially humble yet psychologically complex, her films are hauntingly beautiful and emotionally risky, exploring loneliness, violence and sensuality. Her video installations and drawings have been shown in many venues internationally including the Mori Art Musuem, Tokyo, P.S. 1 Contemporary Art, NY, UCLA Hammer Museum, L.A. and Kunst Werke, Berlin. Her animations have been screened worldwide at various venues and film festivals including Museum of Modern Art, the New York Film Festival’s Views from the Avant Garde and the International Film Festival Rotterdam. She is the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship, a Baker Award and is a fellow of the American Academy in Berlin and the American Academy in Rome. She teaches at Johns Hopkins University in Film/Media Studies.

This conversation took place in my home in Baltimore, January 24, 2015.

MAD: You started as a painter.

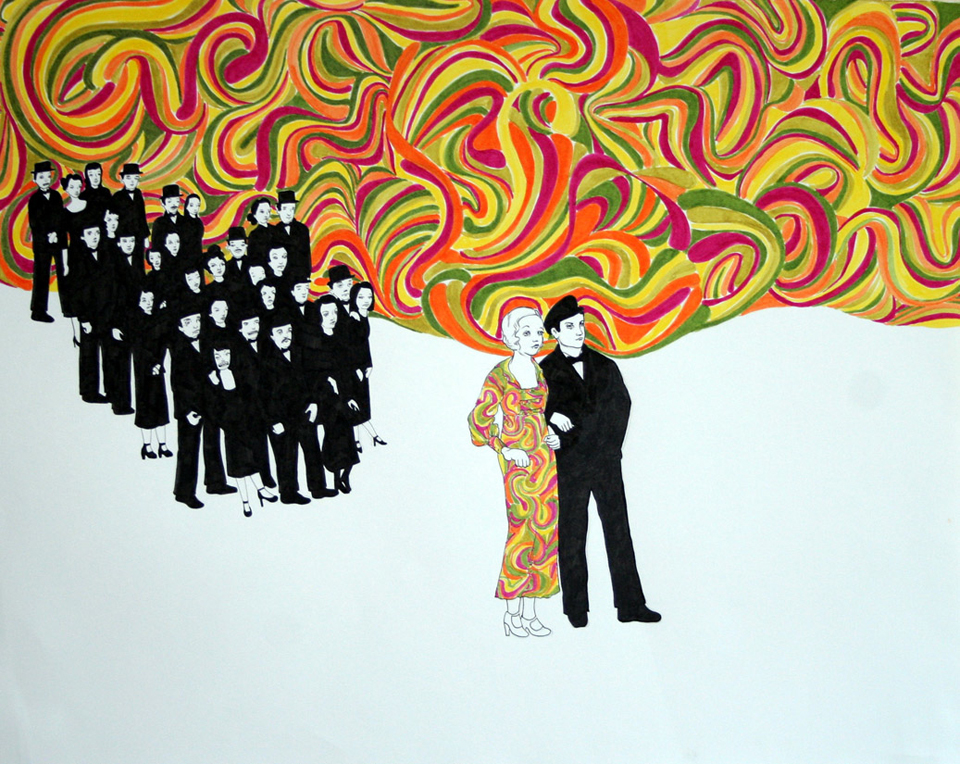

KY: Yes, I was painting small figures, cartoonish figures involved in some kind of struggle and exuding discomfort; pulling at each others’ faces and kicking. They were very graphic, oil on rice paper mounted on canvas. I stopped because I felt as if I were painting the same painting over and over. I had no ideas for things that needed to be made in paint. When I was in grad school at Yale I started to watch movies a lot and fell in love with old silent film, particularly Chaplin and Keaton and early French silent film. When I got frustrated with painting I thought I would make some movies and videos but I didn’t want to work with people. So it was a straightforward decision, ‘Well, I’ll make my people and animate them.” I didn’t know anything about animation but I thought that for my interest in the psychological aspects of relationships, I needed a time element, which I could do with video and the puppets that I made.

MAD: So you worked with hand-made figures right away.

KY: I have always been drawn to bodies, gestures and faces. Although the first time I met Chuck Close I said to him, “You know, you don’t have to use the face for everything.” (Laughter). He thought I was making a joke but sometimes I am so wrapped up in what I am thinking I forget who I am talking to. I really did forget he painted faces. But with real people, actors, the face is so suggestive of their histories, their experiences, they have lines, particular ways their mouth moves. But working with puppets I didn’t have to deal with any of that, there was no history to the character I made, their expressions were fairly blank, so then through their movements and gestures I could create the emotional suggestions I was interested in.

MAD: I often sense echoes of film history in your work, in terms of formal and material issues, in terms of both narrative and experimental forms. Certain canonical films have directly inspired your work such as Robert Bresson’s Au Hazard Balthazar and Jean Vigo’s L’Atalante. What is about those two films in particular?

KY: It is certain scenes or characters that inspire me the most. L’Atalante, like all great films, left me unresolved and excited in this way that allowed it to stay with me. It really did create this new space in my head that needed something to be made to furnish it. The film created that space, maybe gave it wallpaper or particular proportions. In L’Atalante there was a particularly memorable scene in which two characters are separate, in different places but thinking about each other and it is very erotic. The eroticism is created through the cinematography – there is nothing explicit. I was at a point with the puppet animation like I was with my painting; it was a bit too predictable. So I thought working from a remembered image from this film would give my movie a much different start or impetus. I started a puppet animation then decided to do a hand drawn animation based upon the beginning of L’Atalante. I thought I wouldn’t have to worry about narrative structure because it was a given. After drawing obsessively for three months I shot what I had and it was just the beginning of L’Atalante in a cartoon, it didn’t go anywhere. So I went back to the puppets and recreated particular scenes around metonymic ideas about gesture and light and how those things together can create or suggesting some much bigger and greater than what I actually going on. Then with the drawing animation it was a challenge to create an ending sequence that allowed me to find out why I started it. I thought I could simply re-make the beginning of L’Atalante with my drawing, some kind of conceptual act, like Gus van Sant did with Psycho but I realized I’m impulsive. I had to do things like draw a spectator’s head transforming into a donkey. And at the end, Juliette, the newlywed heroine can fly.

While I was working on that I started the Bresson film which was my last very for a long time involving puppet animation. While I was interested in the narrative, I really wanted to explore ideas about grace and transcendence, something about spiritual otherness outside what we have as humans. Bresson grapples with this in all of his films but especially Au Hazard Balthazar. It’s the story of a donkey and a girl that lead very abject lives, the donkey doesn’t have a choice but the girl does. It is a grueling and unrelentingly sad movie; when I saw it I couldn’t stop crying but the crying was a result of the darkness of the film but also a kind of ecstasy that comes from the beauty of the film. It’s like a speedball you are going down and going up at the same time. (Chet Baker waxed poetic about speedballs, memorably.) When I finished that puppet animation based on Au Hazard Balthazar I became more and more interested in non- narrative structures. The challenge and meaning of creating a narrative from an existing narrative was no longer of interest.

MAD: Your puppets seem particularly aware of their own bodies, always rubbing their arms, pressing their fingertips together or twirling their feet. This along with their silence, their muteness, suggests an interiority that we cannot access. It reminds me of something that Maurice Merleau-Ponty said, “Our body is not in space like things, it inhabits or haunts space. It applies itself to space like a hand to an instrument.” The movement of your figures reminds me of music.

KY: They are material, they are objects, they are not flesh, they do not have brains or consciousness, yet the puppets move as if they are aware of the surface tension of the air suggesting that having a body can be a struggle, and they touch themselves as if to reassure themselves that they are there. And when I am animating the puppets I am by myself for long periods of time and I become very aware of my own body and all of the unconscious mannerisms that I have. I don’t use many props so the puppets touch themselves to suggest that discomfort we have with our bodies. Recently I read Chris Kraus’ book Aliens and Anorexia in which she explores anorexia as the negation of the body, ‘de-creation’ I think she calls it, understood through Simone Weil’s ideas in Gravity and Grace. I really understand that; I have fantasized about not having a body and instead being an intelligent red dot that just hovered around. (Laughter)

MAD: The puppets have a duality of being manipulated objects and having the semblance of being sentient beings. Your films suggest that although these figures have free will they are also helpless in face of these larger unseen forces. Which brings us back to Bresson who often explores redemption through self-sacrifice and pain. There is something very Catholic about that, that we negate ourselves in service of a higher ideal or eternal salvation in heaven, always reenacting the suffering and redemption of Christ.

KY: I thought about that definitely with the Bresson work but I was never too concerned with the literal narrative of redemption in my own versions. I think that redemption and paradise comes from the creation of art. Bresson gave us this film, and I feel so strongly about it. Art is religion: art is this transcendence. When it is at its best, when it hasn’t been acculturated, it can be strange and difficult. Art doesn’t have to be understood to powerfully connect with us and move us on a non-verbal level. I don’t think about heaven or paradise, I think when we die we die. But I do think that while we are here, we have art and that can give hope. The ability to create things that try to make sense of things that don’t make sense, is the best thing we have.

MAD: I have been thinking about that a lot lately. The older I get, the less I believe in just about everything involving institutions and ideology. But I believe in art, I have faith in the artistic impulse, and I believe in artists, not in some master / genius kind way but in the simple fact that our works, our gestures, are expressions of altruism in the face of the utter venality of our time. I am not suggesting that artists cannot be complicit in or motivated by self interest but that at its most basic level making art often stems from a generosity of spirit toward some hypothetical other, a future audience if you will. I had this conversation recently at the MacDowell Colony, this table full of writers, composers, and artists many of whom were expressing despair over Ferguson, Syria and myriad other miseries in the world and berating themselves for being self-indulgent artists. But to me that is the thing you should be doing, you should be writing those poems, you should be making those paintings, you should be making it all sing with as much fury and fire as you can muster. Artists undermine themselves when they fall into despair because their works are not changing the world. But that is not how art works, art is a gesture to the future, an act of faith that deep communication between humans who do not know each other can be achieved through images, objects, words, gestures and sounds.

KY: I also think that humans are pleasure seekers and we find pleasure in creating meaning. How do we make a meaningful life? Some people feel good working in the trenches with people who need immediate attention. We try to do things that make us feel needed, useful and connected.

MAD: When you are fashioning the puppets are the likenesses and clothing consciously reminiscent of something else? I think the female figure in I Choose Darkness reminds me of you.

KY: When I was making the figures, I realized like in my paintings, they are all in the same family, and that family is me. I mentioned that I wanted them to have blank expressions that were also somehow pleasant and accepting. In terms of what they are wearing, when I first started they reminded me of my mother.

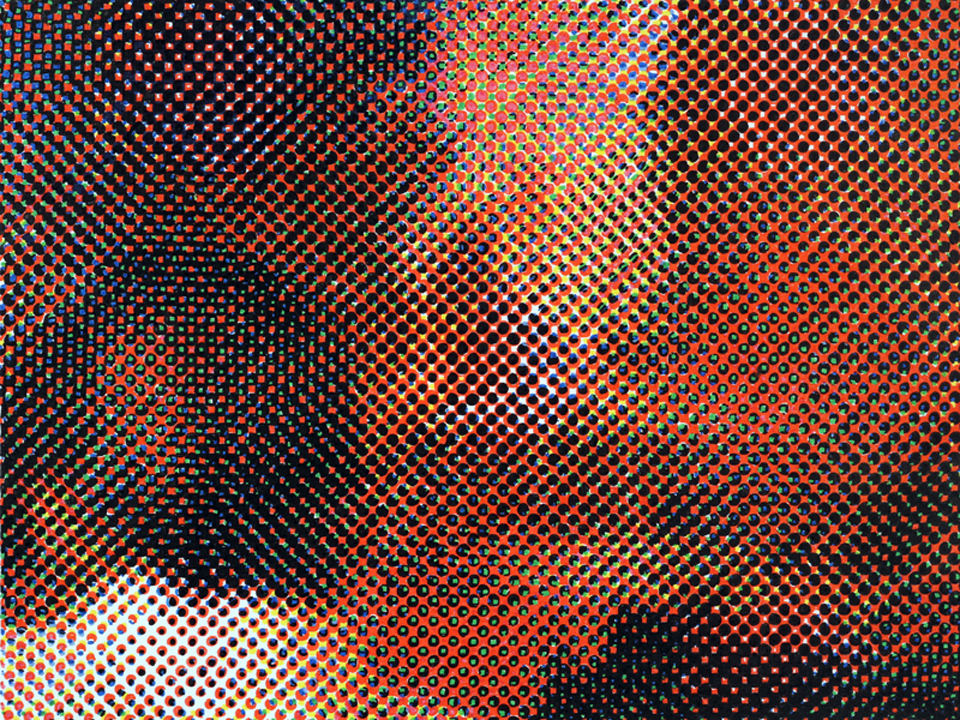

MAD: Let’s transition a little bit. You move between working with hand-made objects, hand-drawn animation and working with found or appropriated footage often in the same film. There seems to be this dance, or tension between the haptic and the distant, things often seem close-up and faraway simultaneously, which for me creates a kind of vertigo or disorientation that is perceptual and psychological. Having said that I wanted to ask about your film Audition that is about 4 minutes long. The film begins with repeated image of a stripper moving across a stage, you have rotoscoped it and the image is very pixelated and degraded. Can you describe your process?

KY: I took a short scene from The Killing of a Chinese Bookie by John Cassavetes and output it as a series of stills and each of those images I pixelate in Photoshop. I redraw each frame over a light box using five different colors for the pixels. Ultimately what you see is an imprecise hand-drawn pixilation because the dots are never exactly the same. The process took forever and I only got through thirty-two frames, which is about 2 seconds of screen time. Around that time I had the opportunity to see Einstein on the Beach again, Phillip Glass and Robert Wilson’s opera. I was reading about it and thinking about repetition, I think it was Walter Benjamin who said there is no such thing as repetition only persistence. Also repetition allows meaning to be emptied out and kind of forces you to notice other things and perhaps find other meanings. So I stuttered those precious frames and repeated them, insistent maybe upon my love of each frame, Cassavetes film and/or the process.

MAD: Those pixels create a kind of unstable visual barrier that you have to look through to get to the image, which points to the process of perception itself. And as you just described, the image repeats in such a short loop that I began to think of Muybridge’s Studies of Animal Locomotion. And then half way through the film it jumps to seemingly unrelated footage of hands leafing through a book of photographs of 19th century Japan. The shift was so sudden and unexpected I initially thought it a non-sequitor. But then I started making a connection between the invention of photography, which is a marker for the dawn of the media age, and these two images, the rudimentary animation of the stripper and the Orientalist photographs. They seem connected to me historically in terms of how the camera is a tool of cultural perception as well as a recorder of individual experience.

KY: I am interested in voyeurism and objectification, so with Audition you have the back of the man’s head watching the figure move, you don’t necessarily know she is a stripper because of the pixilation, she almost looks like a ghost floating across the stage. Like Muybridge, as you suggested, the scene keeps whipping back to where it started and the viewer is put in the position of the man’s head. The song that I use in Audition, by Bo Harwood, is the source sound connected to the image in the original film. It is so full of longing and that longing is also in the photographs; the song acts as a kind of glue between those two disparate parts. In the beginning you are denied the song as whole, similar to the image, and then in the second section, with the Japanese photographs it bursts forth and presents itself.

MAD: In a number of your films there is an exploration of a connection between intimacy and violence. Your film After Hours opens with footage of two women in the moment before a kiss which is interrupted by a puppet animation in the next scene. We see a doll or puppet sitting in a chair; he seems to be in some kind of holding cell or interrogation room. Another figure arrives holding a baseball bat and the attack is sudden and disturbing.

KY: Intimacy and violence intersect at times. I think the way I put them together is related to the Surrealist idea of synthetic criticism and the flow of metonymy. André Breton and Jacques Vaché used to go to the movies and hop from screening to screening, watching only fragments of various films, so at the end of the day they were left with all of these marvelous images that turn into something other than what the original films intended. When I began After Hours I had 3 strong images that felt the need to be together. Violence is a sub-theme in a lot of my work but with After Hours I was thinking about specific acts of violence that were going on in the world. The challenge was how do I present a general idea about violence without context or emotional involvement. Which is why I went back to puppet animation for the first time in a while. For that particular scene I was thinking about a room at the end of David Lynch’s Inland Empire. I wanted the puppet victim to be androgynous and the man with the bat to be all business. I was also thinking about sound and I had this very specific sound / image in mind – the sound of Bluebeard dragging one of his women by the hair down a flight of steps. So when the image goes black you continue to hear the body being dragged across the floor, you hear the door close, and the suggestion of a body being pulled down stairs. The sound carries the memory of violence beyond the visual experience.

MAD: I want to get back to the hand-made and the hand-drawn in your work, the haptic versus the mediated, because as we discussed before you will often combine hand made footage with appropriated footage. But even the appropriated footage has a visceral quality that comes from interference; it appears textured or degraded. I like how it disturbs the assumed transparent window of photography and film, that the image is an object as well. I am wondering if it has to do with your background as a painter, that physical involvement with your materials is an essential aspect of your method.

KY: For me things have to be hand-made. Even when I am shooting things on my TV, I capture the texture of the image and even the way I hold the camera, move in while focusing, move the camera back away from the screen, this kind of self-conscious camera movement stands in for the hand. In my films I try to create a constant shift between you and the object and me and the object. The poet Charles Olsen had this idea that everything, even a chair, is constantly moving. We know that with things that are alive but objects are also constantly moving and changing. There is no such thing as stillness and in a way there is no such thing as death because there is always a constant regeneration. I am the kind of person who wants to work by myself in my studio with my books, my stuff, my pens, my paper and my TV because that is where my life is, where my world is. … (long pause) Sad, isn’t it? (Laughter)