Josef Astor

That photography is intimately connected to history may be a common observation. But just as some histories seem more alive than others, some photographers are more vividly connected to the people and places of their time. Josef Astor has been called a ‘Photographer’s Photographer’; his images are theatrical, dramatic, funny, beautiful, challenging and technically impressive. For 30 years he has been photographing artists, musicians, performers and a variety of idiosyncratic citizens of Manhattan’s cultural underground. He maintained as studio at Carnegie Hall and led the heroic but ultimately failed struggle to keep the longtime residents from being evicted. He documented these efforts in the film Lost Bohemia in 2010.

His photographs have appeared in Vanity Fair, Rolling Stone, the New Yorker, and many other publications. He is a recipient of the prestigious Infinity Award from ICP and teaches at the School of Visual Arts in New York. Curated by the musician / artist Antony Hegarty, a generous selection of his work was on exhibit at Participant Inc. in New York from May 31 to July 12, 2015. Antony wrote of Josef’s work:

Josef Astor’s images capture the space between moments, a difficult and penetrating stasis. The portraits selected for Displaced Persons are multifaceted, unnerving, and surreal. Staging and photographing his peers and muses, Astor intuitively documented key players from intersecting pre-millennial and pre-Internet dance and late-night performance subcultures, assembling a constellation of artists and hybrids who took it upon themselves to reflect a largely oblivious world back on to itself with venomous innocence and shocking self-possession. Astor, in all his subtlety, is one of those hybrids.

This Conversation took place at Participant Inc. on July 9, 2015.

MAD: This show at Participant was curated by the musician Antony Hegarty, (he’s now known as ‘Anohni’) known perhaps most notably for his band Antony and the Johnsons. How did he come to curate your work? Did you ask him?

JA: No, just the opposite. He knows me very well and loves photography. One of his favorite photographers is Peter Hujar. Back in the day when I was starting out you were in either of two camps, Peter Hujar or Robert Mapplethorpe. It was very stark, you couldn’t be on the fence about that and I was always Peter Hujar. So we first bonded over that and I used to hang out at the Pyramid Club where I would see Antony’s performance group Black Lips.

Anyway, he knows me so well that he knew that I would never get it together to sort through my pictures to organize them for an exhibit. I had procrastinated for so long that I had enough work for four or five exhibitions. He staged an intervention (Laughter). He called me and said ‘Hey Josef, lets look at some pictures’ and I said ‘Sure when do you want to come over’ and he said ‘How about now?’ I tried to say no but he insisted. He could be a curator, he has very strong opinions and has terrific taste; luckily for me we agree on almost everything. He even helped with the hanging of the show.

MAD: This selection of photographs represents a very specific time period.

JA: There are a few that are outside that, but yes, generally they are from the mid-1980s to the early 1990s. They were taken in the East Village or were of people I first met in the East Village. This show happened because of Antony but Charles Atlas is someone who is also very present, not only as a subject, but also because many of the people in these images were also part of his world, especially the dancers and performers like Leigh Bowery and Dancenoise.

MAD: You went to Syracuse University; did you study photography there?

JA: No. Here’s how old I am. They didn’t offer photography in the art school. I was a painter and in hindsight many people can see that is a strong influence in my photographs. When I was about to graduate I realized I was one credit short, so I took a photography course in the Journalism school. The U.S. Navy for some reason taught the program, and it was like boot camp. The teacher was like a drill instructor. But I didn’t study photography as an art form until I came to New York and got jobs as a photographer’s assistant.

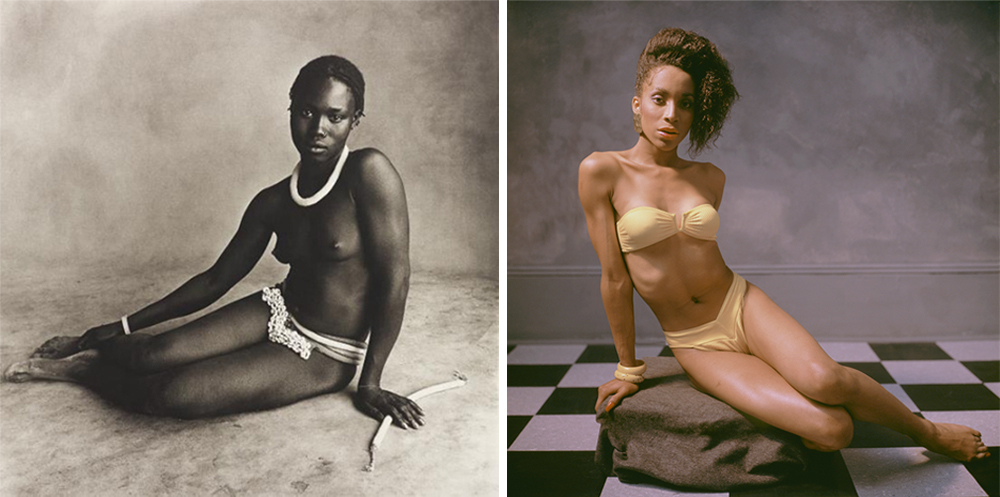

Left, Irving Penn, Nubile Young Beauty of Diamaré, Camaroon, 1969

Right, Josef Astor, Octavia Pemberton St. Laurent, 1987

MAD: One of the photographers you assisted was Irving Penn.

JA: There are so many points in my life when I have just been lucky. I was sitting at the bar in the Pyramid Club sometime in the early 1980s, worrying about my future. I was kind of mumbling my concerns about needing a studio and getting serious about my life when a guy sitting a couple of bar stools down said ‘I’m moving out of my studio at Carnegie Hall’. That move, that studio, changed everything for me. What did you ask me?

MAD: About assisting Irving Penn…

JA: Right, I remember loving Irvin Penn, a friend of mine at Syracuse, a sculptor named Toots Cavanaugh, she used to steal books from the library and she had stolen an Irving Penn book, which I loved although I was not doing photography at all. She dropped out of school and gave me the book. Some years later when I was actually assisting Irving Penn, I thought about Toots and how throwing that book at me from across the room probably unconsciously influenced me. It was an omen or a kind of premonition.

Let’s look at this picture in terms of Irving Penn’s influence. This is the earliest one in the show, 1987 I think. This is a picture of Octavia Pemberton Saint Laurent, she was in the movie Paris Is Burning, I knew the director, Jennie Livingston a gazillion years ago. She wanted to do a scene with one of the performers from the vogue-ing balls having a photo shoot. I was there as a kind of prop in the scene taking pictures. I actually had film in the camera but never paid attention to what I shot. Years later when I rediscovered them, they seem like a skewed version of an Irving Penn photograph. It freaked me out a bit because there is an Irving Penn photograph that looks very similar. It’s from his Worlds in a Small Room series of a young African woman.

MAD: And you were not consciously referencing it.

JA: That’s exactly the point. I mean you can learn a lot studying at the university but the sort of master / apprentice relationship I had with Penn really got in there. He was an old man by the time I worked with him. I was really fascinated by his Still Lifes. I loved watching him do them with an 8 x 10 camera and a macro lens.

MAD: You mean like those cigarette butt images?

JA: Yes! That was the period I came in. Irving Penn would have his assistant drive down the street very slowly and Penn would have the door cracked looking down at the gutter armed with a pair of tweezers, cotton and a little box as if he were collecting valuable archaeological artifacts (Laughter). He then made these beautiful platinum prints of the junk he found in the street. He wanted me to spot the images after he printed them. It was a quandary, they were these exquisite platinum prints of junk found on the street made with an 8 x 10 inch negative and it was impossible to tell what was a spot from the negative and what was a picture of dust.

Also Irving Penn’s work ethic was something I really noticed. He did not take shortcuts. Another thing that might surprise people was when we were setting up a shot he would gather the three assistants and he say something like ‘Ok fellas, let’s imagine we are looking at this in a naïve primal way as if we have never taken a picture before.” It seemed odd, after all he was Irving Penn for God’s sake! but I knew what he meant by wanting to see naively what was in front of his lens.

MAD: Let’s look at some specific images on the wall and talk about them.

JA: OK, This is a good place to start. This is Charlie Atlas and his boyfriend Joe Westmoreland in the picture it looks like Charlie is picking up a blind male hustler on the street.

MAD: What about that background? You have another picture of this in the show; it’s the façades of two incongruous businesses next to each other, Howard Johnson’s and a gay strip club.

JA: Yes, The Gaiety. This is the New York that doesn’t exist anymore that you wish was still there. I took that picture as a background for a series of pictures that use screen projections for the backdrop. They are not digital, they are all made in the studio. It was a front screen projection method that used a beam splitter, basically a two-way mirror. This is old technology that was used in films before they developed the green screen process.

MAD: The light is strange, as if the subjects are in some kind of otherworldly place.

JA: Exactly, you could match the light temperature so that it was more seamless, but I liked that they kind of look cut out or stuck on. It seems as if the figures are there and not there at the same time.

MAD: It’s an imaginary space without needing to build all the props.

JA: Yes. The Gaiety was one of the last old school male burlesque places in New York. I think Madonna made a music video there in the 80s. There was a tinsel curtain and the boys would come out lined up and dancing like the Rockettes. Perhaps surprisingly, it was not a sleazy place with guys in raincoats. It was always the most well behaved, well-groomed crowd. You’d look around and see these gray-haired men in nice shirts and if you didn’t know you might think you were attending a lecture on impressionism.

MAD: Well, maybe that’s where they were before they headed over to The Gaiety. (Laughter)

JA: Bringing it back to Antony, you know his music group is called Antony and the Johnsons. Antony told me it was because of Marsha P. Johnson who was a black trans performer, street queen and original Stonewall activist. Marsha took that name after the Howard Johnson’s in Time Square. There’s a thread that probably no one cares about. (Laughter)

MAD: No it is interesting. At first glance your photographs are very theatrical, colorful, there is a demi-monde quality to them. Like it’s all a show. But what is so great about them is not just the quirky theatrical quality but that there are these really rich and complex histories behind each of these photographs that have to do with old New York and the East Village scene in the 1970s and 80s. There is pre-AIDS gay life….

JA: Yes, Antony pointed that out too, I hope some people can take that away. You seem to know that history.

MAD: I lived in Boston during that period but was in New York every other weekend it seemed, going to many of the same clubs. My friend Philip Retzky lived across the street and I stayed there a lot, so I was part of the scene in a very peripheral way.

JA: There was the Boston scene that came here, Mark Morissroe, Nan Goldin and others.

MAD: And Steve Tashjian who performed as Taboo, I went to school with him at Mass Art.

JA: Well I hope people who are less initiated can sense that.

MAD: One of the reasons I continue to love photography is its connection to history. And like all photographs, yours are grounded to a specific time and place, and although many of these people are still around, that world has largely dissipated, in many ways bought up by capital.

JA: Bought up, is a good way to put it, as I was exiting the East Village you could really see it. Sometimes when I talk about that period with my students, they seem envious, they are very conscious that that freer New York is gone and that money rules everything now. There was a kind of bohemia then like Paris in the 1920s, you could live very meagerly yet have a very exciting life.

MAD: How about this image of Antony? The title is Dead Boy / Girl from 1998.

JA: Yes that’s Johanna Constantine she is a performance artist and muse for Charlie Atlas and Antony, she would go with him sometimes when he was on tour. This is around the time Antony was getting some critical attention. It was unexpected and fabulous to witness him cross over to popular culture, the fact that he has been accepted, celebrated and commercially viable as an artist does give one hope for the future. The other person in the image is Dr Julia Masuda, a Japanese transsexual who used to open his shows by playing Morse Code on the keyboard, beep, beep-beep, beep, that was it! So this was an early incarnation of Antony and the Johnsons.

MAD: Can we talk about making this image? Coming up with the scenario? Antony is on the ground a kind of martyred saint who seems to have been violated in some way, maybe those are wounds where the breasts and genitals are and he has an expression that is both ecstatic and pained.

JA: The two figures are meant to be the spirits or sprites rising out of him. Julia Masuda is standing on a piece of Plexiglas to make her appear as if she is floating, it’s a cheap special effect. Antony imagined all of this; it was for an EP called I Fell in Love with a Dead Boy. I can’t say it was my concept but we were so in sync with things that the image just came naturally. It was almost like we did not have to say anything there was such an understanding between us, the same with Charlie Atlas.

MAD: What about this picture of the pillow with the cherries on it?

JA: I think that is the only picture in the show that has been published or seen before. I was commissioned to make an image for an science article about parasomnia, which is a rare sleeping disorder in which people do very violent things or strange things they wouldn’t ordinarily do in their waking lives.

MAD: And this picture across the room titled Move / Martha?

JA: So many stories here, but to try to make it short, this is Richard Move, who used to dance with Carol Armitage. He was obsessed with Martha Graham and used to perform as Martha in a club in the Meatpacking district, Jacki 60. His show became very popular and eventually people like Baryshnikov and Merce Cunningham came to perform with him. He collaborated with Yvonne Rainer. So the New Yorker decided he was cool and asked me to make a picture, I think they ended up publishing a black and white version, not this one.

MAD: But the light and color in this one! He is like a frozen idol in the moonlight. How did you do that?

JA: It’s very simple really, it is one key light from high above, and another behind him for dimensionality and not much else, obviously if he put his head down it wouldn’t work. It certainly references old pictures of Martha Graham. Speaking of, I took some of the last pictures of the real Martha before she died. It was difficult because she was so old, arthritic and gnarly. I didn’t want to make a scary Joel Peter Witkin image of her. I think it was for Interview Magazine. She had someone with her who told me ‘absolutely no close-ups of Miss Graham’, and while we were setting up the shot she would nod off and he would scream ‘Martha!’ and clap his hands and she would raise her head toward the light.

MAD: (Laughter) I am so sorry to laugh….

JA: It wasn’t funny at the time. I mean Halston was there to dress her, fabric was being flung back and forth, it was crazy and one picture could not capture all the things that were going on under the surface. She was just a shell of what Martha Graham was so I decided that I could either do a gnarly Diane Arbus version of Martha Graham or make a picture to honor what she represented and that’s what I tried to do.

MAD: It’s an homage.

JA: Yes, it was and in some ways I try to do that with most of the people I photograph. I try to recognize the moment they are in, professionally, personally or just existentially. When you are involved with a scene like in the East Village, we didn’t think this was just a finite period of time. I didn’t feel like I was documenting it because it would be gone some day, no one thought that way but in some sense that what photographs do in retrospect.

MAD: Here is another picture of Antony.

JA: It’s called Skewed Halo because he asked me if I was going to retouch it because his halo is skewed. This image is directly across from the portrait of Leigh Bowery who influenced Antony and many others.

MAD: Could you talk about why Leigh Bowery was important?

JA: He was way ahead of his time or, out of his time, I should say; no one could find a place for him. What he did was to make these extraordinary surreal body sculptures, although they were clothing. Someone once suggested that he could make money if he started a clothing line and he said that he hated the idea of anyone wearing his clothes except him. He was his own work of art. He famously posed for the painter Lucien Freud. But in terms of club culture and club fashion, especially Taboo in Britain, he was the center. Charlie Atlas collaborated with Leigh for his 1984 film ‘Hail the New Puritan’; Leigh did the production design as well as starred in the film.

JA: I want to tell you the story of this picture over here.

MAD: Who is it?

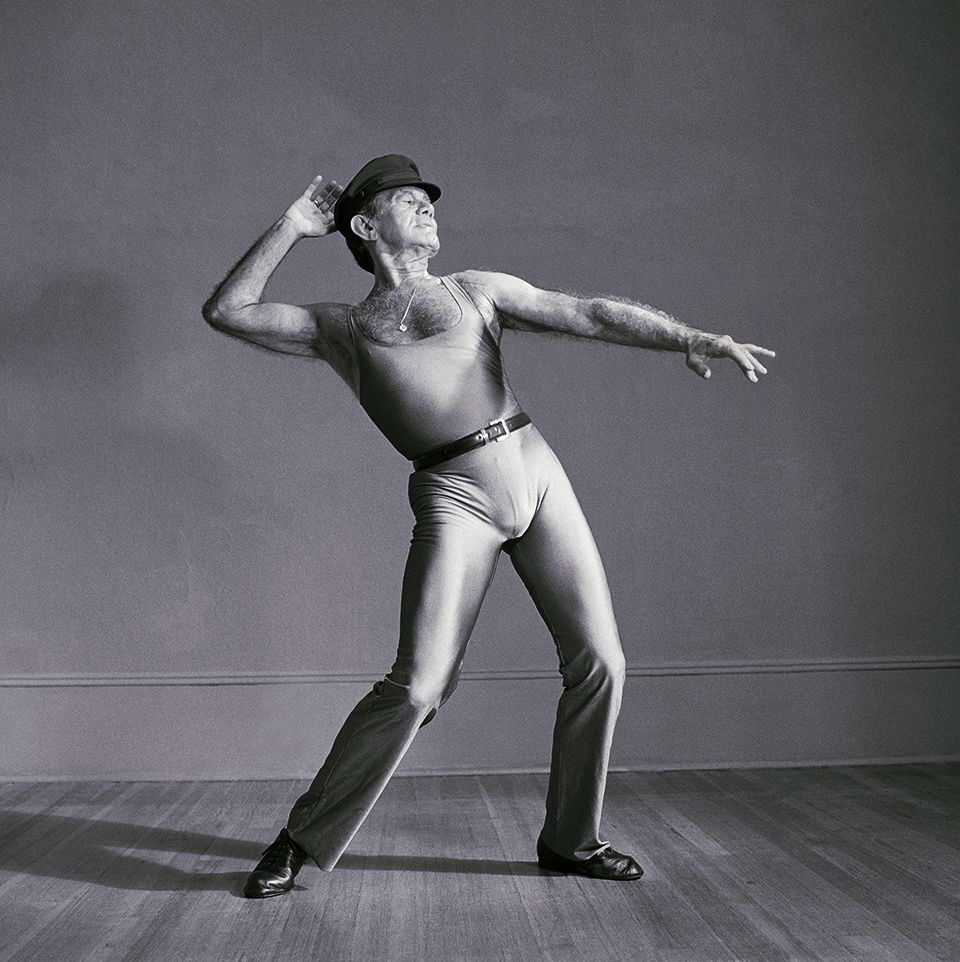

JA: This is one of the most obscure people as far as anyone outside the dance world is concerned, except for Charlie Atlas who found him or rediscovered him. The photograph of Luigi was commissioned by Dance Ink magazine. I had no idea who he was and Charlie said ‘Show the picture to any dancer’ which I did and they not only recognized him they were in awe. Apparently he was this legendary jazz dancer and teacher of the ‘Luigi Technique’ (‘jazz hand’ gesture). He was ‘Mr. Jazz Hands’ and if you see anyone make that gesture, if its Liza Minnelli or Madonna, that’s Luigi. He was a spectacular classical dancer as a young man and was in a terrible car accident. He came out of a coma completely disfigured and disabled. Through intense physical therapy he not only walked again but also re-trained himself to dance not as a classical dancer but as a jazz dancer who innovated jazz technique.

MAD: There is such a strong thread that connects most of these images around art, performance, dance, collaboration and culture in the East Village in the 1980s and 90s. I am not a nostalgic person but one of things I am feeling right now is a real sense of risk and invention, personal and artistic that many of these people were involved in. The art world today is so career-oriented, professionalized and academicized. Although there is much talk about subversion and transgressing taboos in contemporary art, mostly it’s a rhetorical position that feels safe, careful and calculated, as if very little is at risk.

JA: I’m glad to hear you say that. I don’t think art can come from a discussion or a theory; it comes from a process, an involvement with materials and people. It’s not that I don’t have an idea when I start making an image but I want it to morph into something I was not expecting, it has more validity for me if it happens that way. And many of the people that I have collaborated with, including most in this show, work intuitively, we have that in common, and perhaps that is why the relationships lasted so long.