Jane Gillooly

What image is conjured by the term ‘filmmaker’? There are several conventional or stereotypical notions: the ambitious Hollywood wannabe, the avant-gardist obsessed with flickering colors and grating sounds, the fervent documentarian wanting to change the world, the indie director assembling a tiny cast of unknown actors for a film shot in its entirety in a two-room Brooklyn apartment. Whatever the cliché images of filmmaker are, Jane Gillooly does not fit any of them. Over the last 20 years Jane has been slowly building a powerful and unique body of work that on the surface seems disparate in style and content. There is a surrealist children’s tale in Dragonflies, the Baby Cries, there is investigative journalism in Leona’s Sister Gerri, an enigmatic meditation on the impact of HIV on social relations in Swaziland in Today the Hawk Takes One Chick and Suitcase of Love and Shame allows the audience the creepy thrill of listening in on a secret love affair from the 1960s. What connects these films is storytelling, of course, but thrumming just below the surface is a common pulse of empathetic curiosity about particular individuals’ struggles when history, politics and personal crises conspire.

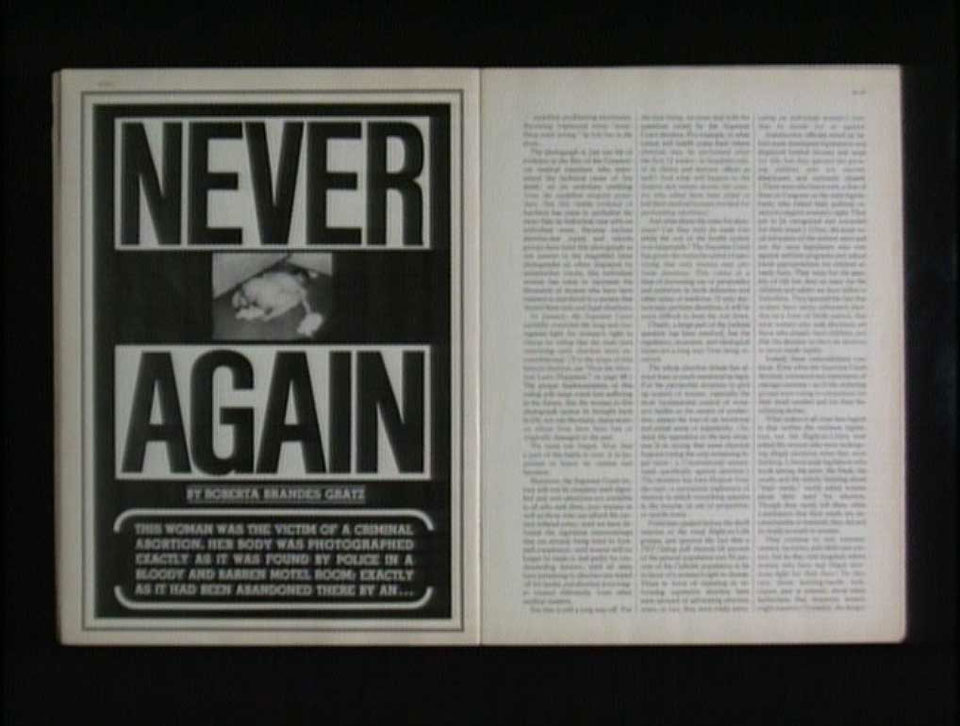

Jane and I have been friends since 1979 when we met as students at Massachusetts College of Art. What struck me then about her and her work is still true today. She has an unwavering personal and political commitment to witness and speak to injustice. Yet she is never self-righteous; she is equally committed to the art of narrative, how it is constructed and how complex and often hidden things can be made accessible. Her first film Leona’s Sister Gerri is unforgettable, I screen it regularly when I teach History of Photography and each time I continue to be moved by the depth of its feeling. Although relatively conventional in structure, the straightforwardness of its approach is the very thing that allows it to be so thorny with issues of the politics of reproductive rights, the ethics of representation privacy, shame, and the unexpected consequences of desperate choices.

Jane teaches at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. She was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2012 /13. Her most recent film Suitcase of Love and Shame has screened internationally in venues such as the ICA in Boston, the Ann Arbor Film Festival, RedCat in Los Angeles and the Visions du Reel Festival in Switzerland. It will have its New York premiere with the Film Society of Lincoln Center on April 15, 2014.

This conversation took place at Jane’s home / studio in Somerville Massachusetts on November 28, 2013.

MAD: Is there a Gillooly sensibility that runs through your varied films?

JG: I am often asked that question. It is a difficult one for me to answer, perhaps because I am so close to it. I can feel the similarity in my films more than I can describe it. I do try to balance a commitment to emotional authenticity against a sensorial style of editing driven by evocative images, atmospheres and sounds. The experience I strive for while making films has sometimes been described as a musical approach to editing – articulating a composition between the poignantly lyrical and the brutally direct. I have not made many films and when I do it is because I feel a real compassion for and deep understanding of the complexities of the human emotion that I try to translate.

From a maker’s point of view, I think of my films as collage. I went to art school, not film school and my films get made in the edit room. My process in the edit room is similar to an artists’ studio practice. While I am working on a film I often have objects in my possession that belong to the subject I am researching. I can then have a physical relationship to the experience, not just to the footage. I outline my films in a visual way often inspired by the materials in my possession.

As you know the topics of my films are involved with the problems of the human condition in one way or another. I make a huge effort to refrain from over sentimentalizing. My approach is non-didactic, restrained; I want the story to accumulate through the revelation of small usually personal details so that the viewer is putting the pieces together in the moment of watching. I don’t use “experts” or narration I cut from dialog. With that said, I am certainly directing and guiding without question, I have a point of view, although I try to leave space for the viewer to have an experience and determine an opinion.

MAD: You went to Massachusetts College of Art and you were doing lots of different things, mixed media, ceramics, and performance. In terms of time-based media, you started doing slide shows, telling stories that blurred fact and fiction and also played with image / text relationships. Do I have that right?

JG: Yes, I’d say both blurring fact and fiction and mixing non-fiction with commentary. Right after graduating in the early 80’s I started primarily making photo/text posters – social commentary, agit-prop – that I would distribute or wheat-paste on the street. Some were published in magazines, like Benzene in NYC and the Real Paper in Boston. Eventually the photo / text pieces led to slide shows that combined images and text, monologues, and recorded sound.

The first was No Applause. I was peripherally connected to the movement against U.S. involvement in Central America. My apartment was an occasional ‘safe house’ that was part of a type of underground railroad for El Salvadoran refugees. This first time-based work was a slide / monologue performance piece about a women’s prison in El Salvador. Some prison activists in Boston saw No Applause and I was consequently asked to present it at the women’s prison in Massachusetts, MCI Framingham. Several of the female inmates asked me why I wasn’t doing this kind of work about their situation. They were correct to challenge me, I didn’t even know Massachusetts had a women’s prison until I was invited out there.

I got a volunteer job at the prison, to learn something about it and started going there one day a week. For various reasons I decided to wait to begin an art work until I had been going there for a year, although I was taking notes weekly and writing. I quickly discovered that something like 40% of the women in that prison had HIV. This was 1985/86 and most everyone at that point still thought of AIDS (as it was called then) as a ‘Gay’ disease. These women were completely invisible to the system. The fact that most of them were or had been IV drug users and / or prostitutes didn’t help. Many of them were sick yet receiving little or no attention let alone treatment.

MAD: What was the title of the piece you made in the women’s prison?

JG: So Sad, So Sorry, So What. It was also a slide-audio piece using the voice of one of the inmates with images projected from four synchronized slide projectors. It got a fair amount of attention.

MAD: You were allowed to photograph in the prison?

JG: Yes, eventually. It took about a year to get the request approved. Basically they tried every tactic to delay or thwart my requests to photograph. In the end, I was allowed to photograph as long as no people were in the images. In prison they have what they call ‘movement’ periods, in which prisoners are moved from building to building. Locked doors and alarm signals are involved and it is only between these two alarms when a building or area was empty. I was allowed to photograph for 5 or 10 minutes until the next group arrived in that area. So all the pictures I took in prison are of these empty spaces, a sea of beds, and a deserted yard. I was not allowed to photograph the woman I wanted to work with until she was in a pre-release program on parole. I photographed her on a black background and using multiple projectors I superimposed / dissolved her onto the images of empty prison spaces.

To fast forward to how I transitioned to moving images. Because there was so little material out there on the subject of women, HIV and prisons, many film festivals wanted to show So Sad, So Sorry, So What, but could not easily present a slide audio piece. Continental Cable also asked to broadcast it and gave me funding to adapt it for video. It stayed in distribution for the next 10 years. Although I always preferred those earlier pieces as slide audio works, once I experienced the usefulness of media distribution I knew that the next time I worked on a durational piece I would use a moving image camera and Leona’s Sister Gerri was my next project.

MAD: I suppose for most filmmakers, ideas for films can come from unexpected places. It seems that for several of your films, the idea came from conversations with friends. For example, you had access to the story for Leona’s Sister Gerri through Toni Elka and Today the Hawk Takes One Chick came through Tracey Kaplan.

JG: Yes you are right. I have a personal connection to each subject through a friend or acquaintance, until, Suitcase of Love and Shame. With the other docs having immediate access to a subject or topic through a friend was invaluable in terms of gaining the trust of the people I hoped to film, second only to my trust in my friends’ belief that the subject was worthy of examination.

Suitcase… was different. I knew that I wanted to make a film exploring a personal history through a series of objects accumulated over time. It occurred to me that I could use collections. When we moved into this house I was packing and I came upon my collection of every birth control device or method I have ever used in my life. (Laughter). All of these outmoded or discarded technologies gave a fairly detailed account of my personal sexual history, medical history, sexual politics and the politics of birth control. There was so much information there about the culture and about the decisions I was making as a young woman. It occurred to me that what people keep from their passage in life could be an interesting way to tell a story. A collection acquired over time could tell different parts of a life story. I didn’t know what I was looking for – it could be someone’s kitchen junk drawer. We had one of those growing up, it was filled with all kinds of random things, some useful tools or objects, as well as decades old doodads from my grandmother, all gathered for no particular reason except that they were not thrown away.

The “suitcase” that generated Suitcase of Love and Shame, was discovered on EBay by my friend Albert Steg. He knew I was looking for collections and told me about it. The suitcase contained 60 hours of audiotape recorded over 3 years and other mementos, letters, and pictures kept by a couple having an adulterous affair. The content in the film is sourced from the collection found in the suitcase.

MAD: Suitcase… is a film although most of information is conveyed through sound. First question is why a film and not a sound piece or installation?

JG: Once I had the collection and realized the majority of it was audiotape; I was interested in creating a sound piece for theater. Somewhat influenced by Derek Jarman’s Blue. There would be a beginning middle and end, the audience would sit and listen together, something would be on the screen but the visual would for the most part be non-directive. My first cut was 30 minutes long with no picture and it was becoming clear that the piece could end up feature length. I wasn’t convinced I could sustain the work without visuals and ultimately became excited about being able to invent locations, and play with image sound relationships. Not to mention as a maker I was enjoying myself more and more, hence the dancing cocktail glasses, etc. I sparingly added imagery, trying out different visual devises, while remaining true to the original concept of leaving space for the audience to free associate images. I still felt that the power of this work would derive from people listening to it together in a public space and projecting their own reactions and memories back on the screen.

MAD: Why do you think it should be a communal listening experience?

JG: Because for me, when I was listening to it alone, it was hard to contain my response to it. I was listening to recordings made a half century ago and it felt as if I was in the same room with these two people. The presence one feels while listening is remarkable. I trusted that if I “re-presented” the material carefully I could guide an audience through an experience where they would see with their ears. The listening had to lead the experience. I feel the strength of the work is that the sound/image collage prompts you, and ultimately allows you to imagine what you hear. And of equal importance is that everyone imagines something different.

The piece is also disturbing and I don’t spare the audience from intense feelings of discomfort. I felt it myself, strongly and often, while I was editing. Much of that discomfort is coming from our own sense of privacy that we are confronting during an experience that feels like eavesdropping. Made all the more intense because we are listening with a group of strangers. It is not my intention to abuse the audience by exposing them to the material. As I said I am conflicted yet unapologetic about how I use the material and to some extent the point was to use it to provoke a conversation, not exploit the material.

I was conflicted about what I should include and ultimately left out some of the more explicit descriptions of pathos, sex and pathetic embarrassing lapses in judgment. On the one hand I was censoring what would be heard but I also feel it is important for the audience to experience the raw, painful, reality of the tapes. Partially because I know this to be a rare recording of the private thoughts of two people who secretly and exuberantly lived a lie while publicly denying their passion. These recording are an honest portrayal of an adult experience in mid-century America. Tom and Jeannie were in a sense inventing a form and the tapes capture their desperate desire to escape societies judgment.

Finally as an audio chronicle the tapes are historically significant. After I heard them how could I not share them? Not only for what they say but also in the quality of their individual voices, the textural sounds in the background, and in the remarkable ways they perform for the tape recorder. The whole while you are listening you are aware that when they made the tapes – they believed they were the only ones who would hear them. The recordings are so emotionally revealing.

The narrative itself is not all that unique. If I were to give you the script of the finished film and you simply read it to yourself you would think it a very ordinary story. A man is married, he’s having an affair, and in the end he doesn’t leave his wife. End of story, they have this hot, steamy thing and then it ends. Big surprise!

MAD: It is a performance. They obviously know there is a microphone in front of them and they create or embody a persona for each other.

JG: Yes, but they certainly were not performing for a larger audience. To me they were inventing a form. It’s unlikely they had any friends doing this; they seemed to be aware that other couples would take nude pictures for each other. But as far as creating what Jeannie calls their ‘Memory Libraries’, to keep their experiences alive may have been unprecedented. They were not copying what they saw on You Tube, they developed this form for their own pleasure.

MAD: Part of the experience of this film is a sense of shared discomfort that derives from listening to the intimate secrets two people shared with only each other with a group of strangers years later. Everyone becomes complicit in this invasion of privacy.

JG: Absolutely, I was initially just as uncomfortable as the audience is now. I would be listening alone and thinking to myself that I should not be listening, that I should turn it off, that it wasn’t meant for me. It was important, essential to keep that level of discomfort and although I did not sanitize it, I did dial back the emphasis on some of the sex because I did not want it to overwhelm the subtler aspects of their relationship.

MAD: What about the ethics of that? What went into your decision making process? The many decades that have passed somewhat soften the invasion of privacy, the trespass, but the ethics of it essentially remain.

JG: Certainly I am trying to protect their anonymity. I don’t use their names and you never see them. I avoided certain narrative threads that would more closely reveal who they were. I edited passages to deliberately mislead the audience to think something happened in a different geographic location. As much as possible I try to discourage the audience’s impulse to figure out who they are. You don’t need to know who they are for the film to resonate. But did I have any reservations or ethical argument with myself about whether I should use this material? Not for a moment. (Laughter). I knew that I would be able to disguise their identity and I just felt strongly that the material was unique and should be heard. In the tone of their voices, how they constructed sentences, in the pauses between words, the texture and detail of the background sound, the references and importance of popular culture, we get a personal report of what these two lovers (average Americans) were concerned and preoccupied with during that period in history. As I had mentioned earlier, we think we know what mid-century American life was about. We also have a generic, clichéd image of who initiated the sexual revolution of the 1960’s. We associate that with youth. Tom and Jeannie were a generation older than the college age free spirit image we usually associate with the sexual revolution. How this compares to a contemporary audience obsessed with sharing private intimacies on social media is uncanny.

MAD: Your film creates a kind of abstract dialog, because they are not speaking directly to each other but instead are recording monologs that they send back and forth. So in the mind of the viewer an extended conversation begins to cohere and what we are given is access to is the most intimate, fundamental, and personal way in which two lovers express and negotiate desire and pleasure, frustration and satisfaction. This is historical material that is more revealing about how people actually lived than any broad observations about generational experiences.

There are so many interesting similarities between Leona’s Sister Gerri and Suitcase of Love and Shame in terms of secrets and how they are both portraits of the same era.

JG: It was the exact same time. 1964 was the year that Gerri was pregnant by her married lover and the crisis point in the adulterous affair between Tom and Jeannie. People would ask me why I decided to make a film about abortion, but I wasn’t making a film about abortion, I was making a film about shame. In a profound and sad way, Suitcase… and Leona’s Sister Geri overlap. Gerri didn’t die of an abortion, I mean technically she did, but she died because she was pregnant by a married man, she was afraid of her estranged husband, she was ashamed and couldn’t speak to anyone about it. She wasn’t intending on having an abortion, it was illegal, birth control was still illegal, and the moral code that everyone was living under forced her to silence. In Suitcase, these people are revealing the secret pleasure experienced without the fatal consequences that killed Gerri.

MAD: Let’s talk about your film Today the Hawk Takes One Chick, like your other films, there is a ‘big’ story which is HIV / AIDS in Swaziland, but lots of layers bring the story to other places such as generational relationships, gender roles in Southern Africa and even landscape.

JG: HIV is the backdrop. The film I was making was about caregivers, who are in large part grandmothers. HIV, drought and poverty are the three factors that collide and out of this an empowered role for grandmothers rises in this community.

This film, like the others is about a moment in time. These elder women’s lives were radically altered because of a disease that they did not have themselves. On the one hand they lived with constant trauma, crisis, loss and grief. But on the other hand they were now living these tremendously purposeful lives and in positions of authority that they would never have had if it hadn’t been for HIV. As more of the middle generation died the grannies in my film assumed places of respect and authority. The oldest grandmother cared for multiple orphaned children, another became a community organizer, health care lecturer and built and coordinated (along with 5 other women) a food hut to distribute meals to orphans. The youngest grannie had trained to be a school nurse, and was now traveling between villages and homesteads and became a spokesperson for HIV care; she was invited to speak at the U.N.

MAD: The experience of watching Today the Hawk Takes One Chick is phenomenological. Without introduction or exposition, one is dropped into a rural world primarily inhabited by older women and children. The light, sound and landscape are utterly unfamiliar to me, yet as I watch I sort of become acclimated in a slowly unfolding way. It is a very immersive and sensual viewing experience. I felt like I was straddling the border of knowledge, not only in terms of distance and geography but also in terms of what I know about humanity, how communities and culture are organized. Even though this is a documentary about the material lives of these people, there is something post-apocalyptic about it, because people have to re-imagine their lives in relation to an unfurling catastrophe.

JG: It would have been entirely impossible for me to make a film about what was developing over the many years of the most intense crisis. The first year I traveled there, Swaziland was the country with the highest rate of HIV and the lowest life expectancy. I made only two trips to Swaziland for a total of 10 weeks. I could not expect to follow a subject or follow up on most of the events as they unfolded. Faced with the limits of how much time I could spend there I used my time recording what I could of the experiences of three grandmothers. I talk about that film as a poem, a layering and accumulation of moments and details. As they reflect on each other I hoped the audience would get a sense of place.

That community was reinventing their lives and social and tribal relationships. Many of the women were doing things that previously would have been unthinkable. The homesteads are passed down through the male line, so sometimes all the men are dead or the heir is a child, to have a woman head of a homestead was unheard of before HIV. Children run some of the households because there are no adults left at all. In a sense, it is the end of life, as they knew it, but an opening of a whole new world. There is a speech you should read by Stephen Lewis. He was the UN Secretary-General’s Special Envoy for HIV/AIDS in Africa. When he stepped down he wrote about the future of the African continent resting on the strength and the gifts of African women. He is so right.

MAD: You are a very political person, but you are not interested in polemics. If I superficially describe your films as about HIV / AIDS, abortion, homophobia, it sounds like a laundry list of ‘important’ topics, and if that was all I knew about them, I might suspect a kind of parasitic relationship to content that seems to afflict some artists who make banal work about topical things yet claim significance because the subject is important. But your films are not that at all, these big topics hover around the edges. Your films are about how individuals experience their specific personal and cultural circumstances. You privilege the integrity of the individual lives of your subjects over your personal political agenda. Did this happen by default or by design?

JG: I think that’s just my personality. I learned as a child in a large family – I am the seventh of ten – it is never about me. I have learned to listen as I wait my turn. I feel like I am a good observer and when I am gathering material I can be patient. I am able to open up a subject because I naturally take more time, and they may be willing to fill in the empty space. I know now that my natural ability to adapt to another individual’s pace can coax surprising things out of a person or a situation, and I don’t close them down by asserting my opinion. With that said I do have opinions. I hope that by the omission of balance in the way I edit my work, my opinion is known.