Eva Respini

Eva Respini is Curator in the Department of Photography at The Museum of Modern Art. She has organized numerous exhibitions on contemporary art and photography at MoMA, including the critically acclaimed Cindy Sherman retrospective (2010). Other exhibitions she has organized include Boris Mikhailov: Case History (2011); Staging Action: Performance in Photography since 1960 (co-curated 2011); Pictures by Women: A History of Modern Photography (co-curated 2010); Into the Sunset: Photography’s Image of the American West (2009); Artist’s Choice: Vik Muniz (2008); New Photography (2012, 2009, 2007, and 2005), among others. She is the author of Cindy Sherman, Into the Sunset: Photography’s Image of the American West, co-author of Fashioning Fiction in Photography since 1990, and a contributor to other museum publications. She is co-curator of the 30th Anniversary edition of New Photography (2015).

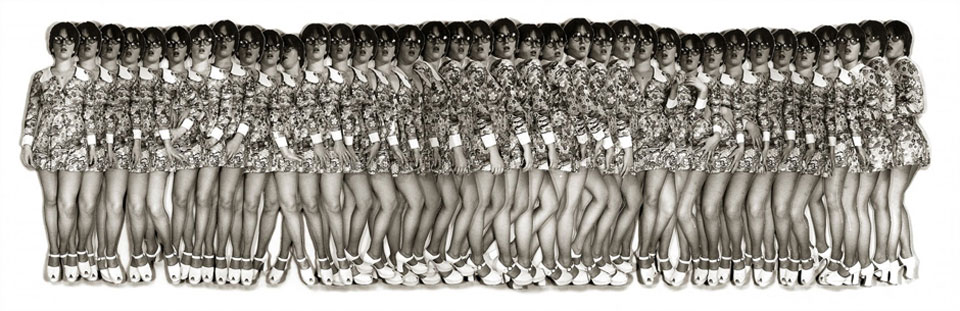

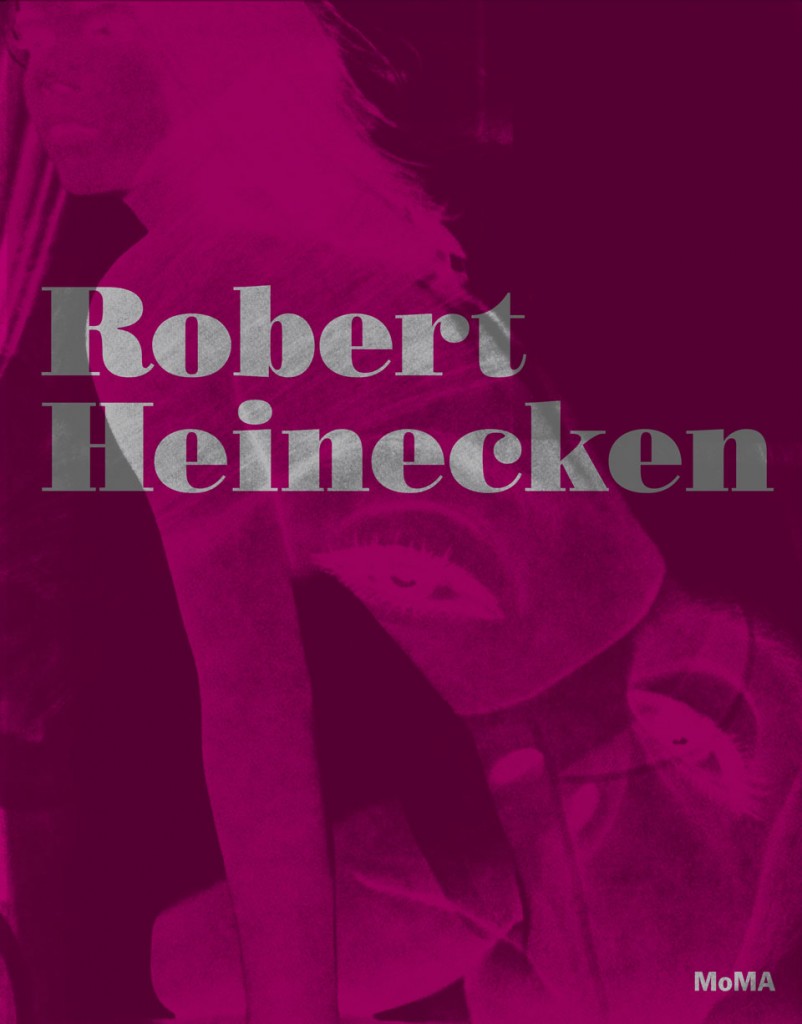

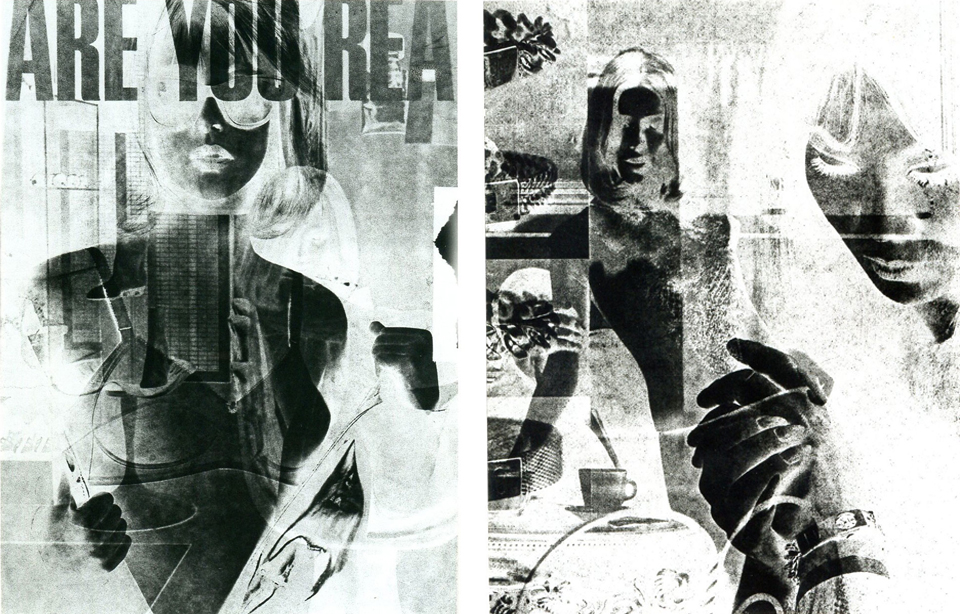

Respini curated Robert Heinecken: Object Matter that recently opened at MoMA and will be on display until June 22, 2014 after which it will be presented at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles from October 5, 2014 to January 17, 2015. She also authored the catalog, which is the first comprehensive publication on the artist since his death in 2006. Heinecken, whose proto-postmodernist work in photography in the 1960s, 70s and 80s, was an influential artist and teacher whose work has been critically neglected for decades.

This conversation took place at the Museum of Modern Art in March 2014.

MAD: What were you doing before you came to MoMA?

ER: I like to say that I grew up at MoMA. I have been at MoMA going on 14 years, I started my career here as a curatorial assistant, so in a junior capacity working on other people’s shows. I was promoted over time and began working on bigger projects. I did work at a commercial photography gallery and as a research assistant at the Whitney Museum, and at Artist’s Space, but all of those positions were very brief. The majority of my career has been at MoMA, in the Photography Department.

MAD: Were you an art history major?

ER: Actually I was a double major, in art history and comparative literature. When I graduated from college I had two job offers: to be a front desk girl at a gallery or an editorial assistant at a publishing company. I had two paths, publishing or art, and I went for the art. But being a curator you publish a lot, I love books, and in photography the book is almost a medium onto itself.

MAD: Did you ever make images; were you pulled that way at all?

ER: No, not really. I took art classes and did analog photography in college. While in graduate school, which was largely a theoretical course of study, I did take a few painting classes on the side. I had a zine and I was into fashion, my interest is really in visual culture and that has been my entree into photography, so the pull was really in the direction of visual culture rather than being an artist.

MAD: Was there ever an encounter with an image or object in a museum or gallery setting that snapped you into focus and pointed you along the path you have taken?

ER: There wasn’t that one ‘aha’ moment. I did not grow up going to museums or surrounded by art at all, that came a bit later in my life. But I have had several pronounced, visceral moments when I had encounters with physical objects in the museum that I had only seen in reproductions. Two examples I can give are a Man Ray Rayograph, one of the most significant ones called The Kiss from 1922, which I had seen numerous times in reproduction and in art history classes. I was cataloging objects and you have a very tactile relationship with images you never have when you are looking at them on the screen or in a book. The Man Ray just took my breath away. The other encounter that I remember very clearly was Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills, which we have in its entirety here at MoMA; we are the only museum to have all 70 of them. I had taken Rosalind Krauss’s 20th Century Art class at Columbia in which there was a session dedicated to Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills, so I was very familiar with the work. But when I saw them early on when I started working here I was so struck by how small they were. In my imagination, these were works of art that loomed large, that had an aura that was larger than life. And to see them so reduced, not that they didn’t have power – they did – but it was remarkable how something that small could have so much power. Then 10 years later I worked with Cindy Sherman on her retrospective so it all came full circle.

MAD: Speaking of objects, in your Cindy Sherman retrospective what really knocked me out where those long horizontal collages she made early in her career, maybe even before the Untitled Film Stills, in which she lined up all these little cut-outs images of herself dressed up as these dorky characters. I had never seen them before and was really taken by the playful physicality of them.

MAD: I wanted to ask you about the legacy of the Photography Department here at MoMA, it must be daunting to some extent to be aware of how this department and this institution, more than any other, influenced the discourse about photography as an art form through most of the 20th century. Is that intimidating or do you just get on with your work?

ER: I feel extremely privileged to work in this department and work with this collection, which is unparalleled in its depth and richness in both the historical and contemporary arenas. I was lucky enough to have known John Szarkowski. I didn’t work under him, but when I first started he was around a lot. And I worked with Peter Gallasi for many years. So on one hand there is the privilege and knowledge of the history of this department and its importance, but I do believe that every generation has to carve their own voice and what I have been trying to do, along with my colleagues, is to try to be a voice of this generation. I am not working against what John and Peter did – I have a tremendous amount of respect for it – but I believe we need to keep up with what is happening today. I think you see increasingly across the museum it is a much more interdisciplinary dialogue than it’s ever been. The artists and projects that I have gravitated toward have been more interdisciplinary, where there is more going on than straight photographs. Heinecken is a good example of that, but so is Sherman, who doesn’t call herself a photographer. While I think it’s important to acknowledge the history of the institution, we shouldn’t be burdened by and not be too navel-gazing about it.

MAD: Szarkowski proposed this famous dichotomy of ‘Mirrors and Windows’ in which photographs were viewed as either windows to the world or mirrors of the artist. It was an extremely influential concept for quite a while, even if it reduced, or left out a lot of work. Do you think there is any rhetorical device like that now to attempt to define the spectrum of the practice of contemporary photography?

ER: I don’t think so. What I love about photography is that it is in the world every day, now more than ever. It is a language that everyone is familiar with; it’s on our phones, on our computers, its on billboards and in magazines. It is becoming increasingly hard to make those gross generalizations or categories. Photography is slippery and that’s why I like it, and that’s why many of the artists I have worked with have responded directly to the slippery nature of the medium. I am not sure you can reduce it to a ‘mirrors and windows’ dichotomy, and to be honest I’m not sure you could do it in the 1960s when John did that show. Photography has so many applications and plays too many roles in both the art arena and the world at large to be reductive.

MAD: You mention Cindy not calling herself a photographer. I was a student in the early 1980s when the anthology Art After Modernism was published which became my bible for new ways of thinking about art and photography. In one of the essays the photo historian Peter Bunnell describes Cindy Sherman as an interesting artist but not an interesting photographer. I did not agree with that statement but remember thinking at the time that that distinction was very telling of a generational shift that was happening in art and photography, in which photographers thought of themselves as artists and artists were using photography and the distinction between artist and photographer was no longer important.

ER: I think for my generation it is a distinction that is completely useless and it doesn’t matter anymore. But I do think it was important to Sherman for her to say that she was an “artist using photography”. It was important for her to acknowledge that she was working outside the conventional photographic discourse. She never studied the history of photography; she did not relate to the more traditional histories of photography, she was looking at performance art and feminist art. For her it was important to make that distinction, and at the time photographer was still a kind of dirty word in some sectors of the art world. But for my generation it just doesn’t matter, you are an artist making photographs one week, video the next, maybe some paintings or performance the next week. Increasingly those categories seem less and less important.

MAD: In a talk you recently gave at the Hammer Museum you compare James Welling, Cindy Sherman and Robert Heinecken in the sense that they were all outsiders to photography that they were in a sense self-taught because they did not study photography formally. This is another thing I really love about photography, that it is consistently redefined and revitalized by people from outside the medium. And the history of photography is changed because of it. I can’t think of any other medium where that is true.

ER: Perhaps in film. But yes, photography is a vernacular medium where you have all these enthusiasts and everyday applications. Although increasingly now with the art market and the fact that almost every artist goes through an MFA program, there is a kind of professional education that happens which makes it harder, in some ways, to be outside the medium.

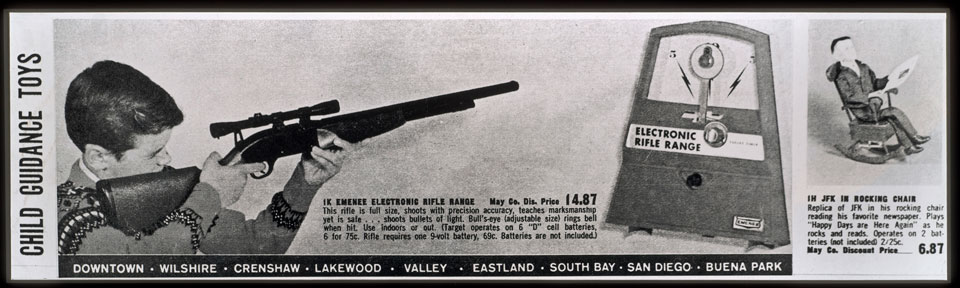

MAD: Robert Heinecken was described as being more interested in fun or pleasure than theory. Which at the time was a meant as a critique, that somehow he was self-indulgent or not serious enough. But if I am honest, I would like to see more artists motivated by fun rather than theory. For all of Heinecken’s issues, that is one of the more interesting things about him, that he is full of contradictions, that he embraced his subjective humanity.

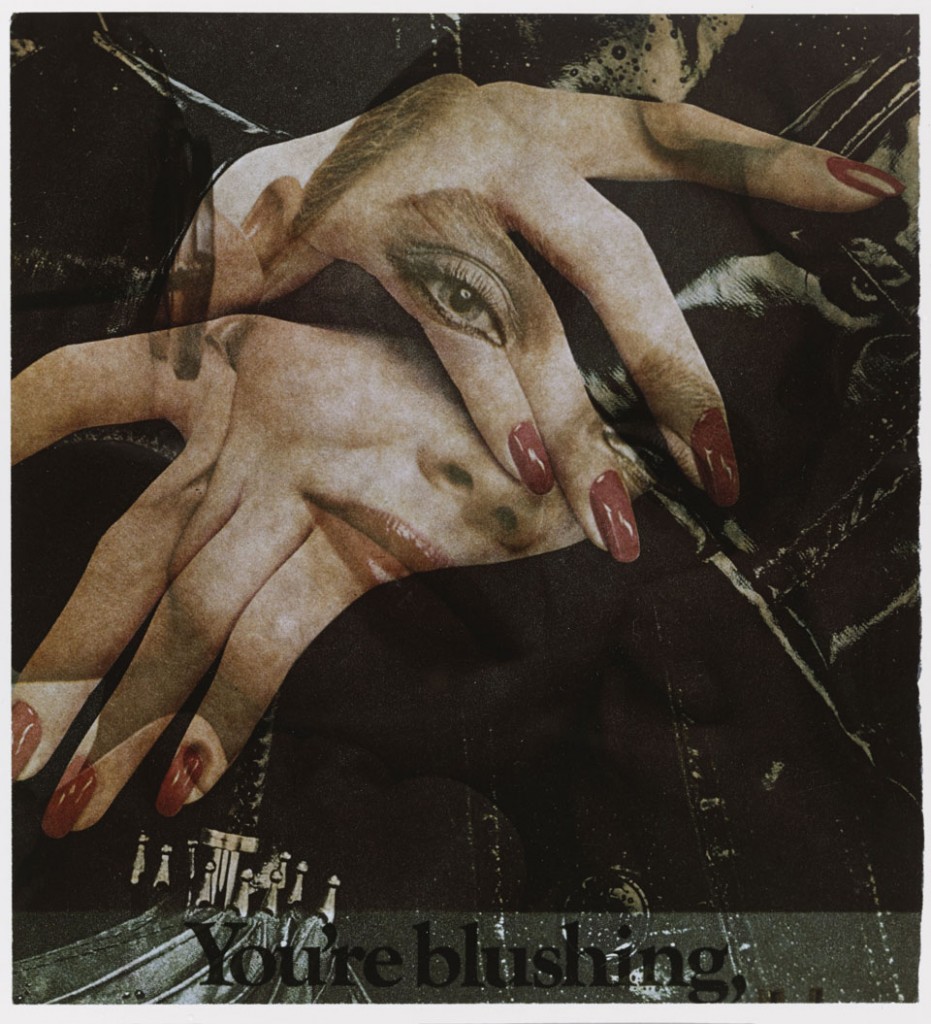

ER: Yes, I agree completely. It makes me go back to Cindy, she does not come from a place of theory even though her work has been theorized by virtually every camp you can think of, everyone claiming her for their own readings. Heinecken and Sherman share a basic impulse to make and create and while certainly the work is thoughtful, it is not overthought. With Heinecken, the great tactility of his work comes from an intuitive place of making with his hands, of going through this iterative process in which images are transferred from one medium to another and yet another.

MAD: Heinecken’s opposition to narrow definitions of what it meant to be a photographic artist manifested itself in many ways. One of them is this iterative process you talk about which I assume came from his training as a printmaker. Looking at the show downstairs, one of the things that really strikes me, just how many layers we look through to the work. There are frames within frames, there are palimpsest pieces, incisions, and interruptions in the supposed transparency of photography, which was embraced and canonized at MoMA and much of east coast photographers, critics and academics.

ER: When I go through the show it still amazes me how unafraid he was in terms of using new technology, new materials, new processes and as you say, layering them on top of one another. Anytime something came out, some new material or camera, Heinecken was experimenting with it immediately in such an uninhibited way.

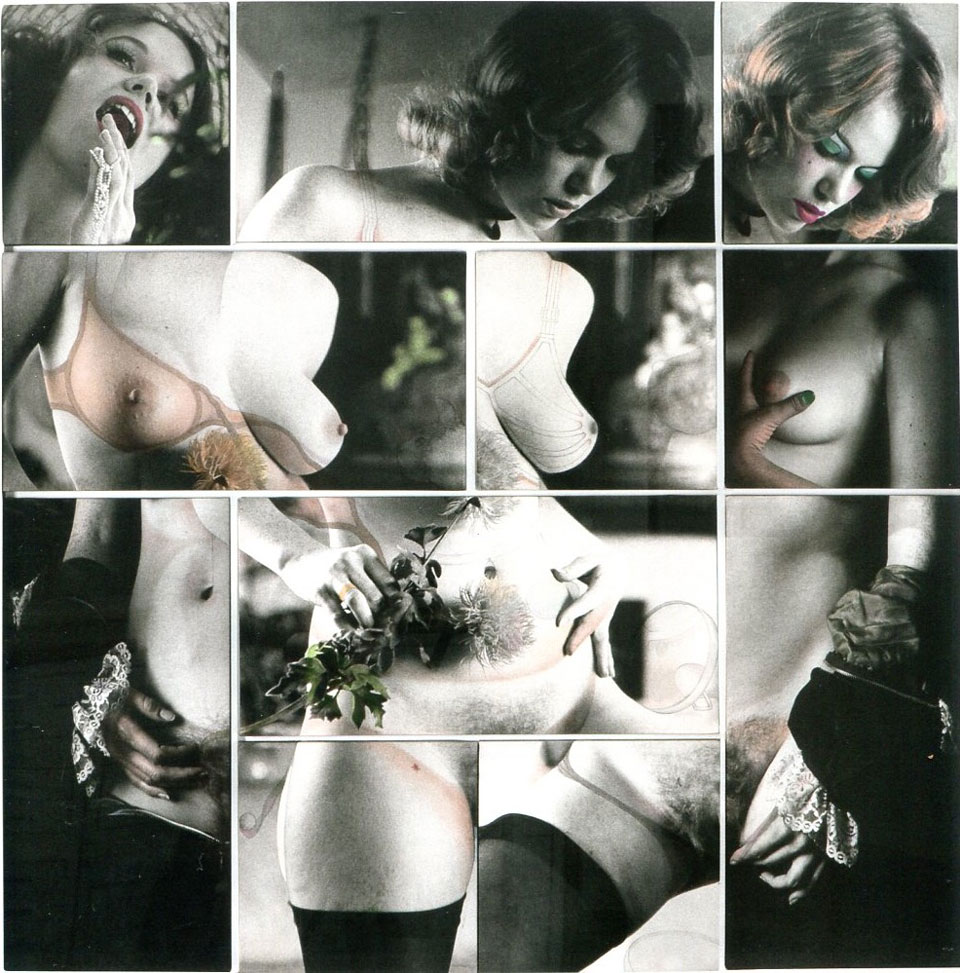

MAD: Perhaps you’ve been asked this question too much but is it important that a woman curated this show, re-introducing Heinecken to the world so to speak, especially after years of almost being a persona-non-grata largely because of accusations of sexism and misogyny?

ER: Several people have told me, including his widow Joyce Neimanas, that Robert would have appreciated that a young woman, not of his generation, was organizing the show. I have spoken frankly about the fact that I am not 100% comfortable with some of the representations of women and some the sexual content in the work. I have conflicted feelings about it, but I have the benefit of a couple of decades of perspective and things have changed. Last night, here at MoMA we had a panel on art and pornography as a part of the Heinecken programming and one of the artists, A.L. Steiner said that Heinecken was a feminist, which I was a bit surprised to hear from her, but she really appreciates his work. Which is not to say that she doesn’t have problems with it. But what is gratifying for me is that because we have a little distance, and perhaps because I am a woman and of a different generation than the people who knew and worked with Heinecken, it maybe gives liberty to look at him in a more objective light. And hopefully artists will look at him fresh without the baggage and criticisms he faced in the 1970s and 80s.

MAD: I studied photography at Massachusetts College of Art in the early 1980s; Nick Nixon was probably the most well known of the faculty at that time. Many of the students, including me, took our cues from Heinecken in terms of his interest in media imagery and his physical interventions in the photograph, he was a hero of ours, and if we followed his lead we were consistently chastised as somehow ruining the special purity of photography. So he had that east coast formalism working against him and when the feminist critique happened, his work went almost unacknowledged for almost two decades. So it is really gratifying to see it here at MoMA.

ER: Hopefully there will be broader recognition outside the photography community. That is one of the interesting things about Heinecken, he insisted on a photographic context even though he was rebelling from within. Even though he is not part of the larger history of conceptual art of the last 40 years, people in the photography world still knew the work. There are certain circles of the art world that are not aware of him at all. I am hoping this show will put the work in a broader context. The show is not in the photography galleries, so I am hoping especially young people come in and see his work in relation to Baldassari or Wade Guyton or any number of young practitioners today.

MAD: Heinecken was such an unusual character; he was born in 1931 – came of age in the 1940s, was a marine fighter pilot, went to art school on the GI Bill, started the Photography Department at UCLA in the early 1960s and became a sort of hippie, academic, intellectual, and artistic mentor to generations of artists. But he always had one foot in what I call a ‘Rat Pack’ sensibility, with the drinking, womanizing. He was a bundle of contradictions. In your estimation how much does biography play into your assessment of Heinecken or any artist for that matter?

ER: I think biography plays into the story of any artist and their work somewhat. If artists are making work about their family history then perhaps biography becomes more important. So it plays a certain role in understanding where the work comes from, but with Heinecken his persona loomed large. I never met Heinecken but in the two years of preparing for the show I interviewed a lot of people who knew him – former students, friends, curators who worked with him – and I came away with the impression of a guy who was charismatic, larger than life, but also quiet and reserved at times as well. His persona does play into the reading of the work and this image of his macho swagger was a significant part in the feminist critique of his use of pornographic imagery. It is important to know as much as possible about the artist but also refrain from infusing too much biography into the work because hopefully good works of art stand apart from their maker so that generations later, the work can be appreciated without all the biographical background.

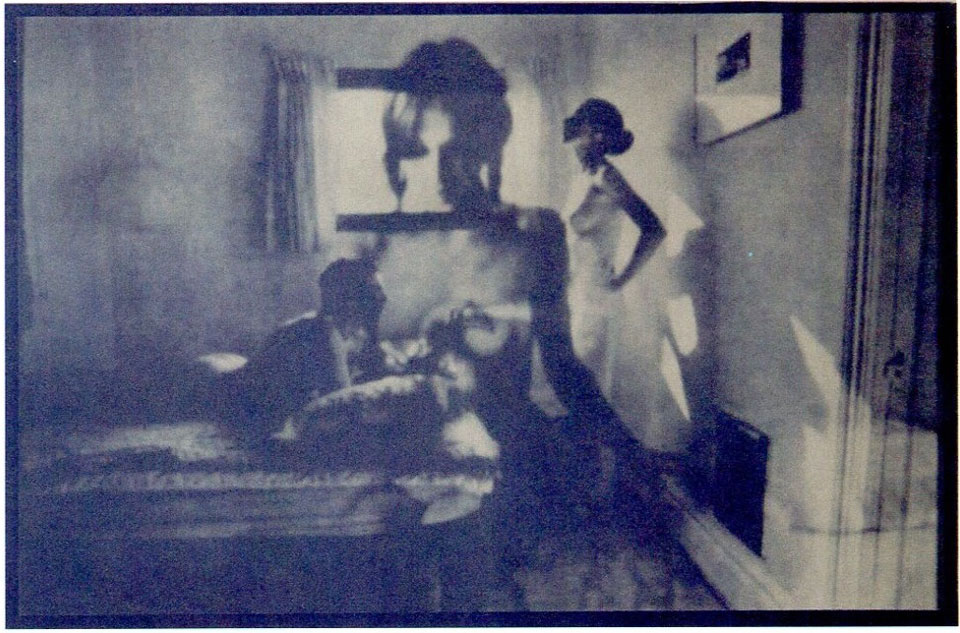

MAD: One of the surprises in the show for me was a group of picture called Vanishing Photographs from 1973, which are images made from multiple negatives from other photographers and the images are not fixed, so they are transitory as they darken and fade over time. Again we can see Heinecken in opposition to the fundamental rules of photography – using multiple negatives that are appropriated from other ‘fine art’ photographers and then allowing them to essentially disappear over time.

ER: I love those. They are a bit of an anomaly in his larger body of work. The other photographers that he uses are Jerry Uelsmann and Les Krims, and according to all the notes that I found he used their work with their permission, but when we got in touch with Les Krims to ask him if we could reproduce on of the images in the catalog, he was very surprised that his image had been used in this way. There are 12 images from this series and we show 4 at a time and switch them out.

In terms of process and the interest in the chemicals of photography there is one other work that I feel is related and that is the Susan Sontag piece where he is intentionally processing the photographs in such a way that they will age and yellow over time Here there is also an interest in the changing image in the same way as in the Vanishing Photographs.

MAD: Heinecken cultivated active correspondence with people in the photography world, other artists, critics, photo historians, and curators including John Szarkowski. So although he was in some ways separate from the East Coast tribe, if you will, he was not intellectually isolated, he was very much in an active conversation with a broad cross-section of the photographic community.

ER: Absolutely, I think of Heinecken as a kind of connector between the east and west coasts with his relationships with the Society for Photographic Education, Nathan Lyons, and the George Eastman House. He developed and maintained strong relationships, he brought a lot of people to UCLA to teach or lecture including Lee Friedlander. So he was a connector during a time when maybe there wasn’t so much of an active dialog between the coasts, or tribes, as you say.

MAD: I wanted to ask you about a couple of other projects and interests of yours. You were involved in a show here at MoMA called Staging Action, sorry I don’t know this, but did you write for the catalog?

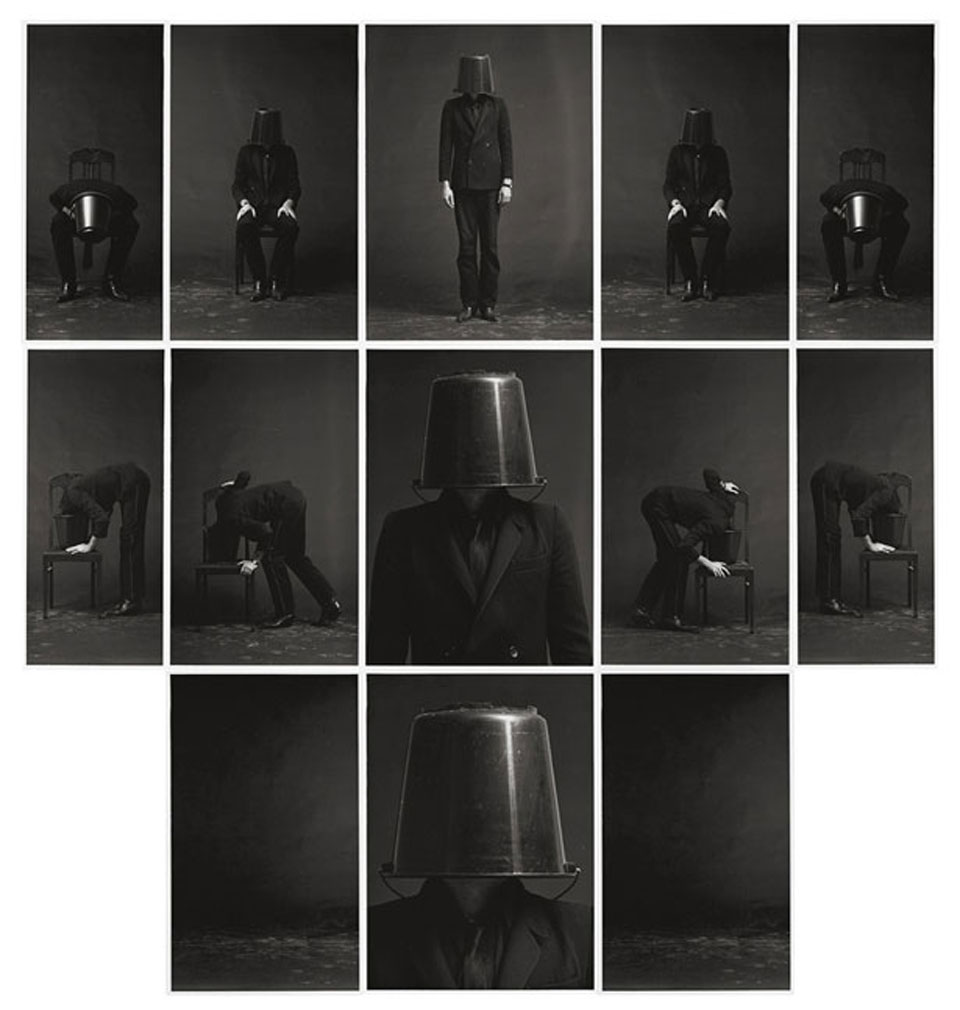

ER: I was the co-curator of that show but there was no catalog, it was all drawn from the collection. It was post-1960s photographic work of performances for the camera, not documentation of performances that were live events but performative works made specifically for the camera.

MAD: I am sorry I missed that show. I am really interested in that phenomenon. It seems to me that that kind of work is almost like a parallel history to tableaux dominated photography that was so prevalent from the 1980s through very recently, like the cinematic narratives of Crewdson, or the theatrical images of DiCorcia, and lots of other people. There is this other trend of people who were informed by performance and its documentation. This kind of work is more gestural, transitory and less narrative. It’s an underexplored territory.

ER: Yes, now performance has entered the museum in a way that it hasn’t been present before, especially this museum where wee have a relatively new department devoted to performance. There is a hunger among the audiences to learn and engage more with performance and not just live performance but also the way that the performative is expressed through different art forms. There is always this gray area with photography, is the photograph of a performance the artwork? What is the status of the artwork? In the 1960s and 70s some documentation was made in a casual manner as a means to capture a live event. Now things are a bit different and you have very sophisticated artists thinking about how the camera, whether it be moving or still, can produce a performative action.

MAD: Some artists in the 60s and 70s started thinking about that, using the ‘affectlessness’ of photography to explore what they called ‘camera space’, in order to differentiate it from ‘sculptural space’. Joseph Beuys for example was keenly aware that the photograph would be a currency of his ideas and in fact, de-saturated performances so they would look better in a black and white photograph. And Chris Burden famously said, ‘I will be shot at 7:45, I hope to have good photographs’.

ER: There was an awareness of the power of the image. I think it is related to the de-skilling of art that was happening in conceptual practices and there photography played a big role. The vernacular photograph was co-opted by conceptual artists; for example, Ed Ruscha hired people to make the photographs for some of his books. There is a history there that hasn’t been told as broadly as it could.

MAD: I saw that the Modern recently acquired and exhibited a Jurgen Klauke work and I was reminded of him and an extraordinary body of work he made in the 1980s The Formalization of Boredom. He is someone who explored the performative in photography, also issue of sexual identity as inspired by Glam music. He is important in Germany but an under-known figure here in the States. What is your take on him?

ER: I agree he is not so well known here and the acquisition that we made in the last year or two is the first acquisition of his work to the photography collection. Its four black and white self-portraits of Klauke in drag, and we exhibited it with other works dealing with identity and performance, including Valie Export and Lynn Hershman. I think Klauke is important in thinking about the ways artists in the 1970s were exploring the plasticity of identity. So there is a kind of proto-Cindy Sherman thing going on but its also connected to the performances of his fellow countrymen, the Viennese Actionists.

MAD: You suggest Klauke as a pre-Sherman figure and it made me think of the many post-Sherman artists who are working right now, someone like Zoe Crosher for example. I am just making up this lineage in my head as we speak.

ER: Staging for the camera, play-acting and theatricality are a part of the history of photography from the very beginning. With Zoe Crosher’s project, what has been interesting is the line between fact and fiction and her interest in the archive, and the veracity and stability of the archive. To a certain extent Zoe is playing with ideas of identity but maybe more so ideas about the archive. That is an idea that has immense currency today, especially with artists working outside the U.S. I am working on a project with the artist Walid Raad who has worked a lot with archives and the line between fact and fiction as it pertains to the photographic and video document. This is an especially prevalent concern among artists working in war torn areas, where archives were not well preserved or destroyed. How to you tell the history of wars or conflict through images in newspapers, or though social media? Who is telling the story? Usually it’s not CNN but a protester with his cell phone on the street in Damascus or Cairo.