Berlin in Two Januaries

I have been to Berlin twice, the first time was January 1983, the return was in January 2011. On both occasions I walked around, took pictures, and thought dark things. Some things changed between my visits. Among the obvious, the Cold War is over and I am no longer a young man. But when I was young, the idea of traveling to Berlin was to imagine a pilgrimage to an unholy site. A place where the schemes for the worst excesses of history had been nurtured polished and unleashed. And if that weren’t enough, Berlin had since become the capital of the Cold War; a city with an 87 mile long anti-monument that came to symbolize a simple but brutal binary reality.

I suppose it was common for American kids growing up in the 1950s and 60s to be esthetically predisposed toward the image of a dangerous Germany. The severe yet elegant Nazi almost exclusively represented the enemy in the war stories that filled our eyes and ears. I was a catholic school child when JFK peered over the Berlin Wall and uttered the phrase “Ich bin ein Berliner’ and we were made to repeat those words after every Hail Mary and Our Father we recited in class in the hope that our prayers would redeem the citizens living under godless communism.

A decade later, during the 1970’s Berlin mutated again in the collective imagination to become a symbol of ‘divine decadence’ a term the character Sally Bowles uttered frequently in the film version of Cabaret. All that back-to-the-land, hippie love crap of the 1960s had finally faded and was replaced by a more urban sensibility in which artists, musician, and writers began employing Berlin as a metaphor for indulgence, transgression, anxiety, and fear. Lou Reed’s tragic rock opera Berlin was released in 1973 and was in reality more of a rewriting of old Velvet Underground songs than an accurate portrayal of life in that city. Yet out of the murky collage of people drunkenly singing and laughing that opens the record, Lou’s sweet voice rises softly:

In Berlin, by the wall / you were five feet ten inches tall / it was very nice / Candlelight and Dubonet on ice / We were in a small café / you could hear the guitars play / It was very nice / oh honey / it was paradise.

I loved that the poetic abjection and melodrama of the album began with such tender and optimistic opening lyrics. It did not matter that during the entire suite of songs he never mentions the city again. The stage had been set, and although I had never been to Berlin, I reveled in the atmosphere.

For me by the mid 1970s, all things 20th century German were of interest. I became particularly obsessed with the Weimar Republic. Otto Friedrich’s Before the Deluge was a bible. I gobbled up German authors such as Heinrich Boll, especially The Clown, Peter Handke, Gunter Grass and East Germany’s Krista Wolf. In art school, German Expressionists became heroes, Max Beckmann, Otto Dix, Kathe Kollwitz and George Grosz as well as their Dada contemporaries, John Heartfield, Hannah Hoch, and Kurt Schwitters. And it seemed as if the messianic Josef Beuys hovered benevolently if inscrutably over this entire lineage of German visionaries.

1977 brought the release of Bowie’s Heroes and the Sex Pistol’s Holidays in the Sun. Like Reed, Bowie used Berlin for atmospheric backdrop of doomed love:

I can remember / standing by the wall / And the guns / shot above our heads / And we kissed / as though nothing could fall / And the shame / was on the other side / Oh we can beat them / for ever and ever / Then we can be Heroes, just for one day

The self-proclaimed anarchist / anti-Christ, Johnny Rotten, was a little less romantic:

Claustrophobia there’s too much paranoia / There’s too many closets so when will we fall / And now I gotta reason / It’s no real reason to be waiting / The Berlin Wall / Gotta go over the Berlin Wall / I don’t understand it / I gotta go over the wall / I don’t understand this bit at all…

I would be remiss if I did not mention the impact German filmmakers had on our punk existentialism. Wim Wenders’ The American Friend, Werner Herzog’s Aguirre, The Wrath of God, and just about anything that Fassbinder did seemed to exponentially expand our notions of what cinema was capable of.

1983

This is all to say that by January of 1983, I thought I was suitably prepared for the sojourn to the capital of the Cold War. My girlfriend Allison and I spent a few days in Paris first, but apparently it made no impression; we vaguely recall a garret room in a cheap hotel, eating lots of croque monsieur and visiting Jim Morrison’s grave. That’s about it.

What we both vividly remember is the train trip from Paris to Berlin, which had to cross into East Germany before it reached its destination. After a couple of hours the train was stopped, without warning, in the middle of nowhere to allow East German border guards to board with actual German Shepherds. Passports were checked, bags were noisily sniffed, and suspicious glances were exchanged. It was all so cinematic; film images of tense moments on trains fired my paranoia. I kept thinking about Jane Fonda playing Lillian Helman in the movie Julia. As portrayed in the movie, Helman was an apolitical artist who felt impotent in the face of rising fascism, she agrees to smuggle some money into Germany in order to support the Nazi resistance. Much tension is wrung from the scene in which her cabin is search and a quietly threatening Nazi officer questions her.

As if to reward ourselves for eluding capture, Allison and I decided to take a meal in the dining car. It was so elegant and old-fashioned. There were lace curtains and leather seats; the meal was served on bone china. And as our eyes imbibed the East German countryside, the dining car seemed unnaturally quiet, emphasizing the angular sound of our knives and forks working the rote kraut and schnitzel. We arrived in Berlin late in the day under leaden skies. We found our hotel and woke up the next morning to be greeted by not the sun but the perpetual dusk of a Berlin January. The cloud layer was so close, dense and undifferentiated, like an enormous dropped ceiling; the temptation was to hunch over while walking down the street.

Without recognizing the privilege, we wore doom and angst like heavy cloaks; it was our fashion. A fashion that we hoped would read as historically aware and sympathetic without commitment to ideology. We wanted to try on a bit of the unbearable dread that we thought every German carried on their shoulders. The unacknowledged conceit was that if we breathed the air of this history we might somehow, ourselves, be more substantial, weighted, more present in the world. We desired a measure of gravitas that could match our dark and demanding esthetic.

I was a photographer / flaneur then. Christopher Isherwood’s Berlin Stories opens with the line “I am a camera’ – an attitude I fervently adopted. I fancied myself a scruffy model after Cartier Bresson or Andre Kertesz, or better yet, Robert Frank or Josef Koudelka. Nothing made me feel more engaged with life than to roam the streets of a city with my Leica strapped in my right hand. There was something predatory to my methods; stalking unfamiliar neighborhoods, back alleys, and ragged industrial peripheries in search of characters and appropriately desolate stage sets to fill my frames. The gray skies created a kind of uninterrupted twilight – perfect conditions for my approach of mixing light sources; dying daylight, a bit of ambient tungsten or fluorescent leaking from a shop or streetlight, and the burst from the tiny flash atop my camera, all combined to emphasize the theatrical and the transitory; my slippery version of the ‘decisive moment’.

I wasn’t interested in photographing adults, or humans in general, people were too specific. The contradiction is now painfully obvious; I desired History with a capital H, and avoided the messy details of actual individuals. Children were OK because they were still unformed – without history. Kids ran the streets like sprites, not quite fixed in time, or fully defined. I spent a lot of time photographing at the zoo, which was virtually devoid of visitors. It was inherently surreal, an empty maze of cages and environments for dislocated beasts. I caught a lonely man in a black trench coat masturbating while he gazed at a napping rhinoceros. I read a story about animals roaming the city during the last days of WWII, after bombs had destroyed the zoo. I tried to photograph the white wolves as if I had encountered them gathered on a pile of rubble and thought of Bob Dylan and Allen Ginsberg while I whispered the phrase ‘desolation howl’ as I pressed the shutter release.

No matter how lost one got in the gardens of Charlottenburg or the labyrinthine streets of Kreuzberg, the Wall beckoned. Since August 13, 1961 when construction on the wall began, the drama of this barrier was inescapable literally and figuratively. Even the most treacherous of borders are somewhat porous, but the Berlin Wall symbolized an unbridgeable divide, a binary opposition without a hint of ambiguity. In the more populated parts of the city there were actually two parallel walls, with a dead zone in between, patrolled by soldiers and dogs. Lots of people had been shot trying to cross this no-man’s land – that negative space between the double- walled boundary.

Approached from the west, the Wall’s surface was encrusted with graffiti, from the poetic to the banal; lover’s initials, political declarations and bits of lyricism like ‘An empty lot, there was a dancing soldier’. I felt compelled to add to it, to mark it in red spray paint with the name of my band Children of Paradise. While this act of tourist vandalism posed no real danger for me, I imagined it an epic violation, as if I had thrown an egg in the face of Stalin or something. Like a sarcastic ticker tape parade, a sudden squall began to clot the air with big misshapen snow clumps. The meteorological mockery was lost on me; the thrill of my transgression inspired me to run through the icy wind – taking pictures without looking. Swinging the camera in arm-length arcs, shaking it chaotically, my flash going off randomly like a very isolated electrical storm.

To cross over to East Berlin was no joke. A foreigner could get a day pass although West German citizens were not allowed. You had to exchange a minimum amount of currency for East German deutschmarks that you were required to use during your visit. The sum was relatively insignificant but nearly impossible to spend entirely, as there were few shops in East Berlin that had anything you wanted. Stationary materials, pens, pencils, note pads and envelopes were passable and cigarettes were good too, not for smoking but for the clunky graphics on the packaging.

In his book The Wall Jumper, German journalist Peter Schneider compared the Berlin Wall to the mirror in Grimm’s fairy tale Snow White. The West looked at the wall and saw a reflection of its own superiority. The east side of the wall was, as to be expected, without graffiti. It was an unblemished wash of gray, as if a dense fog had simply settled in, obscuring any view of the West. As a sign of their citizen’s contentment, maintaining the wall free of personal inscription was a priority for East German officials. And it was kept spotless. I wanted to photograph it from that perspective but after many precious exposures had been attempted, I realized that it was beyond me; that my artistic intentions were no match for the banal and insistent ugliness of that concrete ribbon of oppression. A border guard inquiring after my activities briefly accosted me; I easily played dumb while he rocked on his heels examining my passport.

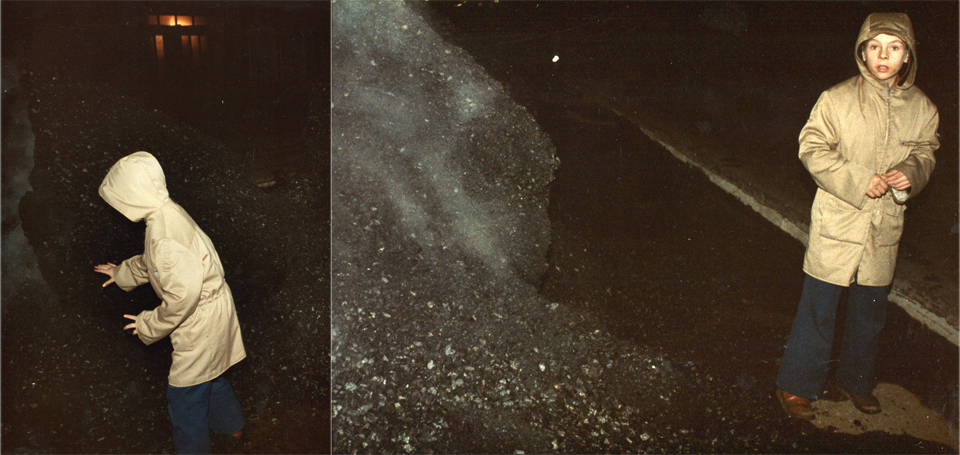

With the dull light of afternoon fading, I glumly walked toward the border crossing to escape back to West Berlin. I was disappointed, I had not bagged my prey, not captured a single interesting photograph. Just then, like a dark mirage, I stumbled upon large piles of steaming asphalt in the middle of the street. There was no sign of trucks or workers nearby, but clearly they had just been dumped there. I grabbed my camera and fired up the flash and began taking pictures immediately. I felt they were OK but lacking, they needed a hook of some kind, a figure or event to provide compositional or narrative tension.

As if in answer to my prayers a young boy, perhaps 10 years old, came out of the shadows. He did not see me as I scuttled behind one of the piles to watch as he pulled his hand out of his coat pocket to tentatively reach toward the glistening heap. I seized the moment, jumping out and snapping away, my flash going off in rapid sequence. Beyond startled, the boy seemed terrified; I ignored his pleading high-pitched voice while I moved closer trying to find the right camera angle. I did not speak or understand German but finally the panicked lilt of the word ‘Polizei’ got through. I dropped my camera to my side and looked as if seeing him for the first time, and was seized with shame. ‘Nein, Nein, Polizei’ I tried to reassure him but it was too late, he ran as if from a monster.

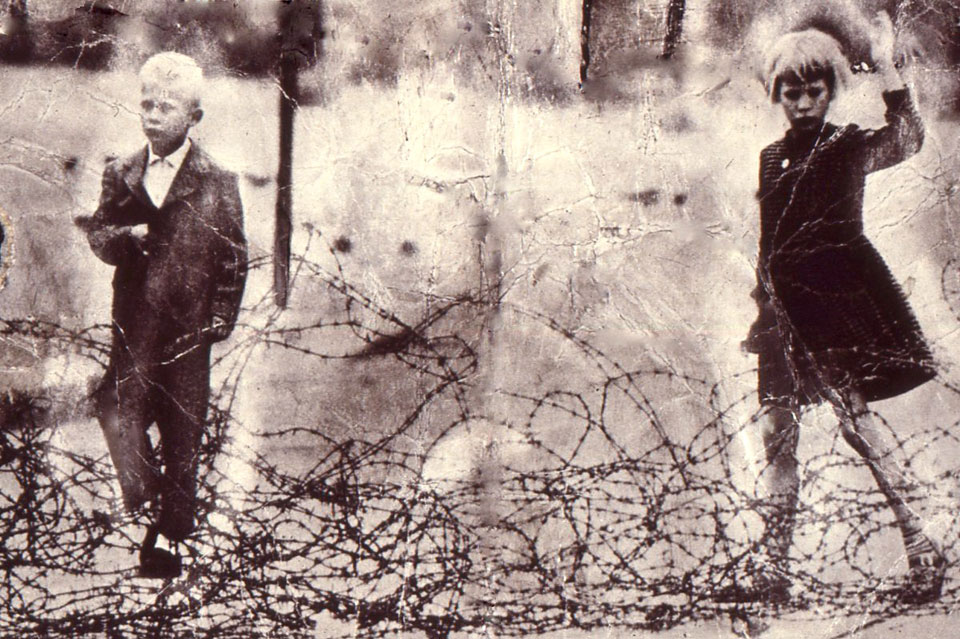

The border crossing at Check Point Charlie had a small museum presenting the history of the post-war carving up of Berlin and the eventual building of the Wall. A time-line with relevant political events was illustrated with documentary photographs of barbed wire being lay down, people scrambling through windows, errant soldiers switching allegiances, John F. Kennedy, giving his ‘Ich bin ein Berliner’ speech and the dead bodies of unsuccessful escape attempts. The gift shop sold post cards with these dramatic black and white images. One in particular haunted me, so I purchased dozens of them. Taken from the western side of the divide on August 13, 1961, we see two children, a boy and an older girl, perhaps brother and sister, on the far side of barbed wire. The boy has a hand stoically tucked into his jacket while the girl raises her hand above her head. Maybe she was offering a simple gesture of hello, an uncomprehending wave to a friend or relative on the other side. Or maybe it was a salute or sign of resignation. But I have always understood it not as surrender, but as a gesture of defiance, a big ‘fuck you’ to the situation, to history and to the photographer.

2011

I am now married to Beatriz, a German woman who is the least angst-ridden person I have ever met. She is patient, tolerant, and optimistic with no interest in heaviness as an affectation. Along with our 5-year-old son, we are visiting her family in Stuttgart to attend the memorial service for her grandmother, who died over the holidays. I am taking a three-day solo trip to Berlin and on the train from Stuttgart I am downloading the Berlin Metro map to my iphone. From our home in Baltimore, I made reservations online to stay at a Holiday Inn. I arrive at the magnificent structure that is the Haupt Bahnhof, take the subway to Potsdamer Platz and employ the GPS on the iphone to guide me to the hotel.

Blame January but the city seems as dim and dreary as I remember. An icy wind bites into my face as I walk down the street thinking about my itinerary. I have planned what might be called the Holocaust and Cold War memorial tour, with a little bit of contemporary art added as respite.

Reunification returned Berlin to its status as capital of the German Republic. In the twenty odd years since the Wall fell, public memorials, museums, statuary, and plaques have spread throughout the city’s domain to mark the seemingly endless abuses of power and its victims. That afternoon I visit the Jewish Museum in Kreuzberg. Designed by Daniel Libeskind it is a purposefully vertiginous experience. One begins the tour in the lower depths of the building where objects confiscated from Jews arriving to death camps are presented as if looking through a keyhole in vignetted glass displays. The entire structure is lacking right angles, which makes every room and corridor feel as if it is closing in, threatening to crush the spirit out of the visitor. Practically gasping for air, I step out onto the street around 4pm where it is already getting dark. I decide to walk back to the Holiday Inn.

I wake from a dream in which Phillip Seymour Hoffman has been starring in a German reality TV series about urban farming for seven years. The enormous orb of the TV tower in Alexanderplatz is blinking about a mile away. Its 4:11 AM, hungry and still jet lagging, I eat chocolate wafer cookies and drink fizzy water while I watch television for several hours waiting for some semblance of daylight to seep into the sky. The Simpsons dubbed in German is faintly absorbing, mostly because Homer sounds like Sargeant Schultz on Hogan’s Heroes. This is followed by a story about the Wok bobsledding Olympics in Innsbruck, Austria and an in-depth piece about a man who rescues lost gloves and mittens, and after cleaning and matching them up, resells odd pairings in his specialty shop.

Day two involved walking to and through the Brandenburg Gate and then down Unter der Linden to Alexanderplatz. My first stop was the Holocaust Memorial just south of the Brandenburg Gate and adjacent the U.S. embassy. The memorial designed by yet another American architect, Peter Eisenman, consists of 2,700 concrete slabs of varying sizes arranged in an undulating labyrinthine grid. As in Maya Lin’s Vietnam Memorial the visitor is drawn into the earth in an unavoidably ritual fashion. A light dusting of snow had turned the gray slabs into frosted cakes, many of which were temporarily and playfully inscribed with hearts and peace signs, names and sentiments in a variety of languages. Among the many controversies that met the design of the memorial when it opened in 2005, was one particularly perverse irony. Anticipating vandalism by neo-Nazis, the slabs were treated with an anti-graffiti coating. It was soon revealed that the company supplying the chemical once manufactured and provided poison gas to the Nazi government for use in the death camps.

For 28 years the Brandenburg Gate was isolated in the no-man’s land between East and West Berlin. The once elegant and grand ceremonial center of the city was reduced to an inaccessible, decaying folly. It has since been restored to its former grandeur although now it is more of a site for Cold War tourism than a triumphal arch. For an hour I sat reading The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks in the Starbucks (which was two doors down from the Dunkin’ Donuts) on the east side of the gate. An Erykah Badu remix provided the background music to Russians reminiscing about Mikhail Gorbachev.

Erected in 1969 as a symbol of socialist know-how, the TV tower in Alexanderplatz soars above everything else in Berlin. Before zooming up to the observation deck I purchased an unusually large falafel sandwich and strolled around the trendy shops while dripping tahini on my boots. I acquired postcards with actual shards of the Berlin Wall in little plastic rounds imbedded within the image like a holy relic. By the time I made it to the top of the tower winter darkness and the low-lying clouds foiled me again. I could barely make out the city, which seemed like an apparition in the particulate mist. Like the return of a vice kicked long ago, I felt compelled to make some images that somehow captured the metaphor. I did manage to take some extremely zoomed in photographs of people crossing the park or the street far below, although they appear as nothing more than smudges in the frame.

My last day in Berlin arrived like an early Easter. The sun came out, not warm but bright and insistent. The murky corners of the city were illuminated with a clarifying matter-of-factness. As I stepped outside the Holiday Inn, my shadow seemed to point the way toward my lunch date with a former student, Laurie, who has been living in Berlin for the last year or two. We met at a museum café, and I am introduced to her newborn son, Jackson. She sings the praises of this progressive, child-friendly metropolis. I come to the slow realization that although Berlin does not attempt to hide its horrific past, it is not stuck there.

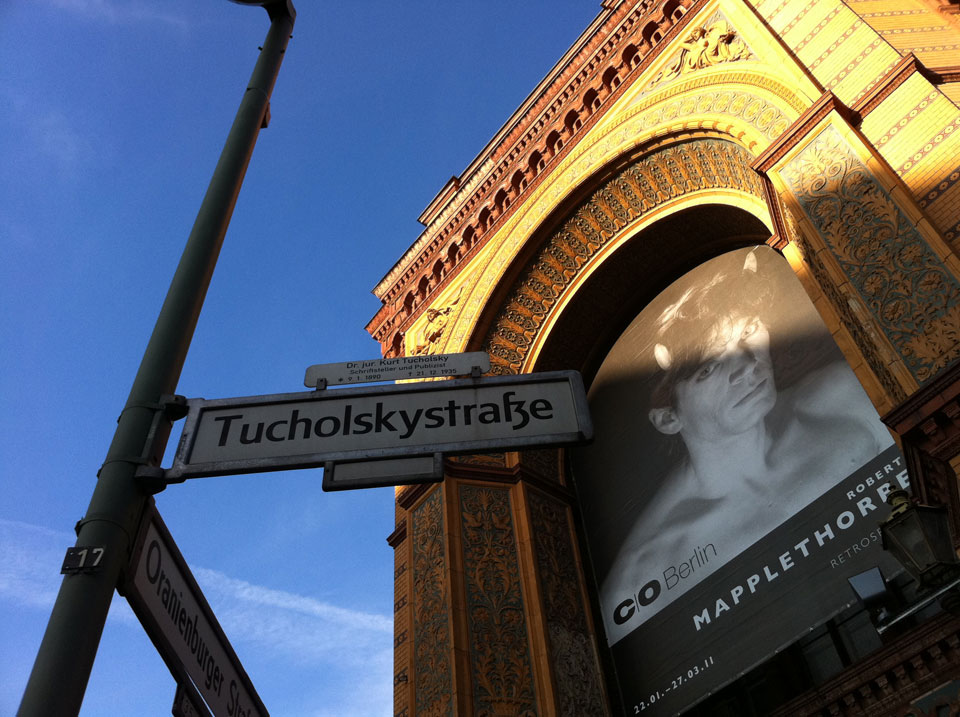

This neighborhood is just north and east of the Reichstag in former East Berlin. The atmosphere reminds me of New York’s East Village in the 70’s and 80’s. Cafes, galleries, artist squats, brightly colored murals; political slogans adorning the sides of abandoned buildings, young people everywhere. There is a Robert Mapplethorpe exhibition on Kurt Tucholskystrasse. Tucholsky was a writer / satirist / anti-fascist who collaborated with John Heartfield in the 1920s. The Nazis threw his ‘degenerate’ writings into bonfires. This random association of two of my artistic heroes animates me, makes me feel connected to history in an eccentric and strangely uplifting manner. History is not some vague, amorphous feeling, but a series of associations through which we are connected with others; those with whom we are intimate and those whom we could never know but nevertheless have found a spark of recognition.

I do not miss the doom and angst of my unburdened youth. Despite my desire for heft and gravity, I photographed like a ghost chasing ghosts; most of the images appear weightless, diaphanous, lacking the specificity of a life lived. I don’t think I could make an ‘art’ photograph now if I tried. What happened to that drive and ambition to picture the world through the shutter curtains, lenses, the shadows and highlights, the silver and dyes of photography? I make photographs now for the same reason everyone else does – to say I was here, and leave it at that.

Unless otherwise noted, all images by the author, 1983/2011