Larry Sultan

I want to be with those who know secret things or left alone. Rainer Maria Rilke

Larry Sultan was my teacher, beginning in 1983 when I entered the graduate program in photography at the San Francisco Art Institute. It is difficult to separate my first impressions of him from the sensory shift I was experiencing living in a new environment. I grew up in stingy Boston and all of the clichés of sensual and hedonistic San Francisco were fresh revelations to me. Pacific light illuminating white stucco and pastel Victorian, fog slithering under the Golden Gate Bridge, the vertigo one felt braking at stop signs at the top of impossibly steep streets, the rows of majestic palms running the length of Dolores Street, calla lillies blooming in the back yard, images of the Guadalupe painted in alleyways and dangling from rear-view mirrors, mariachi bands and aging beatniks, the treacle scent of night blooming jasmine after a night in a smoky bar.

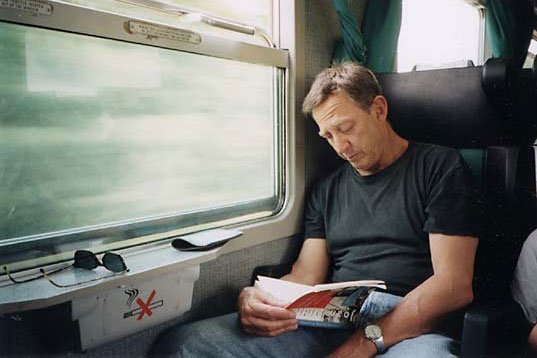

The Art Institute welcomes you with a tiled fountain in the center of a Spanish courtyard, you can pass through a double doorway to the student gallery to behold Diego Rivera’s mural featuring the impressive heft of his backside. The graduate photography seminar met down the hall from the courtyard in Studio 16, a high ceilinged room with huge arched windows and balconies overlooking North Beach and the marina. Once a week for the next two years the graduate students gathered here for critiques and discussion. Larry was often the seminar leader. First impressions are fleeting, fragmentary, and vivid; his boyish hair, brown leather coat, gray suede shoes (were they oxfords?), elbows on his knees while he rolled a cigarette and spoke of secret things. He quoted Aristotle, Rilke and Walter Benjamin. His critiques of student work were precise analyses punctuated by exuberant laughter; he laughed at himself, at pretension, at earnestness, at failure and success.

Professionally, Larry was between his groundbreaking collaborative with Mike Mandel Evidence and was just beginning to work on what would be his opus Pictures from Home. Having studied photography in the social humanist tradition as an undergraduate, I was woefully ignorant of the seismic shift occurring in photographic practice in terms of appropriation, authorship, pastiche and irony, in other words, the whole post-modernist thing. Evidence is a modest folio of 59 photographs culled from various industrial, police and government archives. Each image appears to be highly illustrative, but lifted from their original contexts the images become strangely mute, defiantly uncommunicative. Evidence was the ur-text of my epiphany that the process of photography did not end with the mounting and matting of a beautifully printed image, but that photographic meaning continually shifted in its relation to context, presentation and language.

Larry joked that now he had been labeled a post-modernist and wasn’t sure he could create emotional and sensual pictures for fear of being self-indulgent. Although he laughed about it the dilemma was real. He demanded rigor from his work but did not want to exclude beauty. He had been photographing swimmers underwater and was deeply ambivalent about the results. He brought a box of prints to class and spread them across several tables. I thought they were lovely; pale arms reaching toward the surface, headless torsos gliding through various shades of blue, the water between bodies a kind of liquid confirmation of our connectedness. These underwater pictures made me yearn for freedom; I ached to float there among them, as if I could escape the stubborn weight of my own history. I am not sure that Larry ever exhibited those photographs but I believe that the lessons he learned from making them helped him achieve the acute elegance of Pictures From Home.

As a teacher Larry connected the dots between history, culture, material, process and personal responsibility. He taught me that being an artist is to create your own path both internally and externally. It is perhaps a strange thing to say, but not only did Larry help me envision what it meant to be an artist but I learned so much about being a man from him. Growing up most of the men in my life were drunks and tyrants. I did not really understand at the time that part of my west coast / grad school sojourn was in part a search for a kind of maleness that I could live with. In his humor, generosity, intelligence, fierceness, and dare I say it – handsomeness – I recognized something that I deeply wanted to emulate.

When I graduated from the Art Institute in 1985, in lieu of an artist statement and based upon a vivid dream, I wrote this minor allegory. I now understand that Larry is at the heart of this image.

The ground is uneven, broken earth, shattered boulders. It is difficult to walk. The fog erases any possibility of identification. I am walking in one direction. I think the earth is ancient. There is a tall man a half-stride behind me to my left. I don’t know how long he has been with me. Even this close he is only a vague form in the thick mist. From under his cloak he pulls a trumpet. I cannot watch too closely because I am still stumbling along. He raises the horn to his lips and lets out one long beautiful cry. The mist begins to clear and I see children walking in front of me in pairs, threes and singly. They are moving along in quite a deliberate fashion. Some of them are holding hands. I feel comforted by their presence and their apparent knowledge of our destination. When the note of the trumpet fades, the fog again enshrouds. It is still difficult to walk but I continue by thinking of the sound that clears the mist and of holding hands.

Originally Published in Dear Dave, 7