Kristen Hileman

Kristen Hileman has been the curator of contemporary art at the Baltimore Museum of Art since the fall of 2009. Before coming to the BMA she worked at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden for eight years, curating exhibitions such as Anne Truitt: Perception and Reflection, Ways of Seeing: John Baldassari Explores the Collection and was co-curator of the monumental exhibition The Cinema Effect: Illusion, Reality and the Moving Image. Her first curatorial effort at the BMA Seeing Now: Photography Since 1960 opened on February 20, 2011 a couple of weeks after this interview was conducted.

MAD – You are from Chicago, so was the Art Institute an important place for you growing up?

KH – My mom took my sister and me to the Art Institute all the time when we were little. When I was a teenager I participated in their studio art classes and something they call the early college program. In my younger years, I was definitely interested in the practice of making art. I made the switch partly because my parents were not so encouraging about me going to art school.

MAD – Of course! What parent in their right mind would encourage their kid to go to art school? You would have to be delusional.

Laughter

KH – Yes, well after my diversion to Washington D.C. to study international relations at American University, I found myself drawn back to art.

MAD – I am interested in that phenomenon – How many people turn away from a career or path that may have seemed too fraught with insecurity and then they find a circuitous way to return to their original impulse or passion. For me, when I was a teenager I had a vague notion that I wanted to be a photographer but I had no idea how to do that. So I studied to be a high school history teacher, but as I was about to do my student teaching in a Boston high school – I just kind of freaked out because I couldn’t imagine doing that for the rest of my life. For a long time I thought I had wasted that time studying history but as it turns out the knowledge, the discipline and the notion of historical context has served me over and over again in my life.

KH – Absolutely, for me the benefits I got from my international relations degree were an understanding of the global interconnectedness of the contemporary world, which is so important to the arts, and also clarity in writing. As you know, sometimes art writing can be as much about using and protecting a specific vocabulary as it is about clearly expressing thoughts. When you are trying to communicate political or historical ideas you want to avoid language that obscures. I’m glad that’s where I formed my writing style.

MAD – Well this is jumping ahead but since you brought it up I was going to mention your essay for the Cinema Effect exhibition at the Hirshhorn. First of all, I really loved that show – so congratulations on that. In your catalog essay you begin discussing Dziga Vertov but then you use the film The Truman Show throughout the essay as a kind of supporting structure for your observations about the relation between contemporary art and film. And one of the things that does is to show how art and artists are connected to the larger culture and that art is not necessarily just the province of obscure, esoteric or self-indulgent obsessions.

KH – I think it’s an important thing to do. My experience interacting with artists is that they do see themselves as part of the larger culture, and they seek to respond to topical issues. I suppose there are artists who want to be aloof hermits making work for time immemorial, but most artists are people immersed in popular culture, who not only consume but also respond to and reshape the media of the day. As I was preparing for the Cinema Effect, I was working on another project with John Baldassari who is a film fan. He recommended I watch the movie The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, to see a great cinematic example of the tensions between image and reality. One of the concluding lines of dialogue in the film is a directive to a newspaperman: “When legend becomes fact, print the legend.” When you start to dig into it, popular culture can express pretty profound ideas, ideas that are also examined by the art world.

MAD – Speaking of Baldassari – did you see his show at the Metropolitan Museum?

KH – I did.

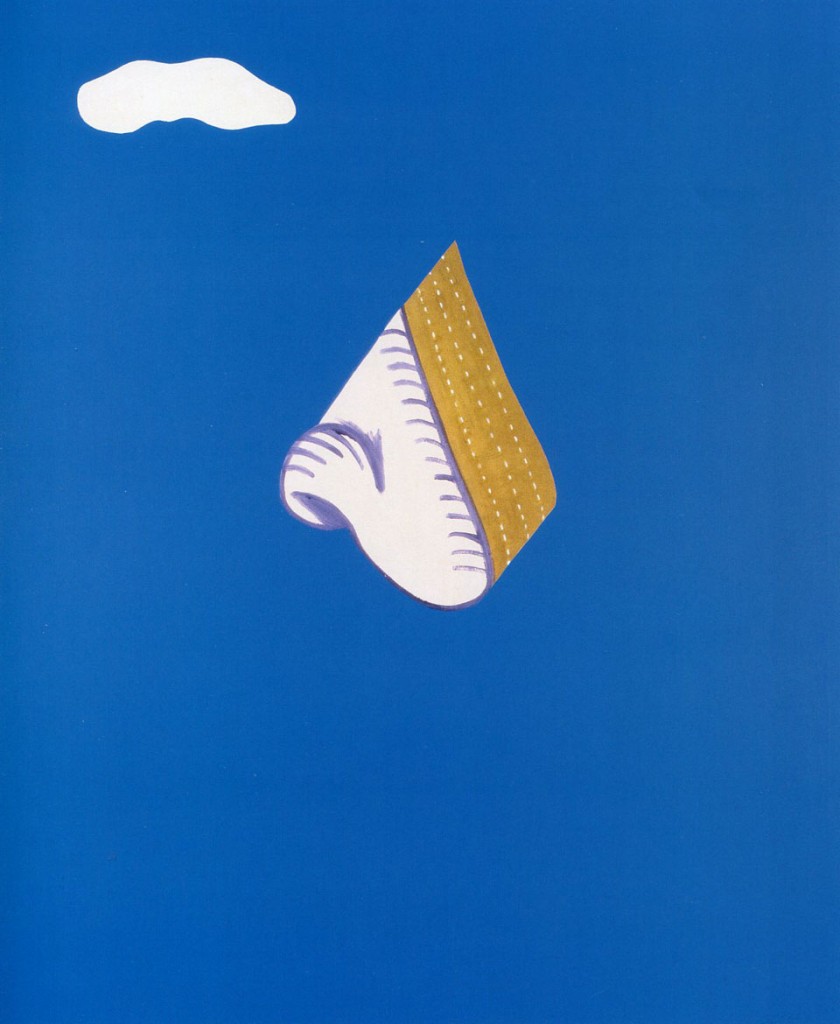

MAD – I thought it was wonderful and it reiterated what a wide-ranging influence he has had for almost 50 years. There is this legend that he burned all his paintings in the 1960s but apparently and happily some of them survived – and they are so terrific like that giant nose floating in the sky with a tiny cloud nearby – so sweet and smart and funny.

KH – And they relate so much to what he went on to do. He really shows us how pictures work. Simple things like covering up some of the image with a colored dot or blanking out a face or exaggerating a nose or ear or whatever it might be, through all those little tweaks you get to test the variables of other aspects of the images. And the larger pieces that juxtapose film stills and other miscellaneous photographs, you get to see how images speak to one another. You could walk through the Baldassari show and pay attention to how his pictures operate, and then walk through the rest of the Met with the ability to look at other pictures more closely and understand or appreciate better how different elements of an image communicate meaning.

MAD – It was interesting to see his show there at the Metropolitan. He’s like the trickster in the cathedral of art – I mean I don’t think he is a blasphemer – he obviously loves and cares about art – but his sensibility can upend the claustrophobic veneration of art objects especially in a place like the Met.

KH – While we worked on the Hirshhorn project his appreciation for both Giotto’s fresco cycles and comic books came up. It’s such an interesting analogy because in both instances there is a narrative communicated through images. One has such an otherworldly and elevated aura around it, while the other is something that circulates every day, but for Baldassari, and I agree, there is more that’s similar about those two ways of communicating than dissimilar.

MAD – I was reading an interview you did with Cara Ober when you first took the job at the BMA. You said that one of the reasons you accepted the job was the opportunity to work with a collection that was broader and deeper. So now that you have been at the BMA for over a year what has surprised you?

KH – Well I have the chronic frustration of not having as much time as I would like to spend in the galleries and examining all parts of the BMA collection. I mean there is never enough time because it’s a very rich collection. But being here has expanded my notion of what a museum can be and what audiences want from a museum. I also feel the transition from working at the Smithsonian and a museum on the National Mall to a museum that is extremely connected to the city in which it is located has added another level of responsibility in terms of taking into consideration what kinds of exhibitions and programs speak to the immediate community that supports and attends this museum.

MAD – You are opening an exhibition soon, which is your first large-scale curatorial project at the BMA – Can you talk about it?

KH – It’s called Seeing Now: Photography Since 1960 and is drawn entirely from the BMA’s collection. In some ways the show is a complement to an earlier exhibition here called Looking Through the Lens. The only artist that overlaps the two shows is Robert Frank, an artist who serves as an important pivot point between modern and contemporary approaches to photography, as well as between early and late twentieth century culture.

Mickalene Thomas. Le déjeuner sur l’herbe: Les Trois Femmes Noires (2010), Seeing Now: Photography Since 1960

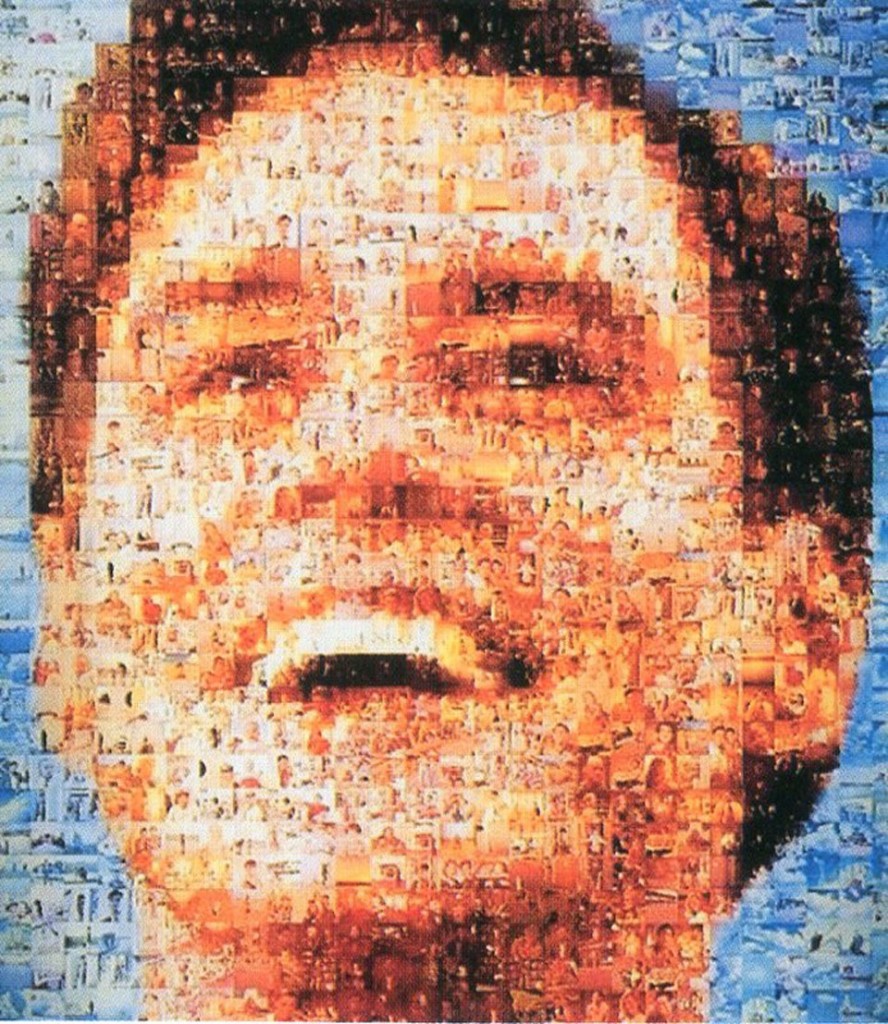

In order to give a comprehensive overview of what we have in the collection, the current show is organized in five broad thematic groupings. It starts with a look at photographers and photographic work that look at pre-existing images. I am trying to suggest the idea that by the 1960s photography was a medium that was quite self-aware. That segues into a section of pictures about people in which, for example, a Cindy Sherman film still from the 1970s is juxtaposed with Garry Winogrand images from his project Women are Beautiful, shot in the 1960s and published in 1975. It is amazing how similar these two photographers works are in terms of how they look, yet the more staged and conceptual examination of Sherman and the candid and spontaneous street work of Winogrand are coming from two very different practices.

MAD – Right, even at this late date their work is discussed as if Winogrand belonged to photography and Sherman belongs to art.

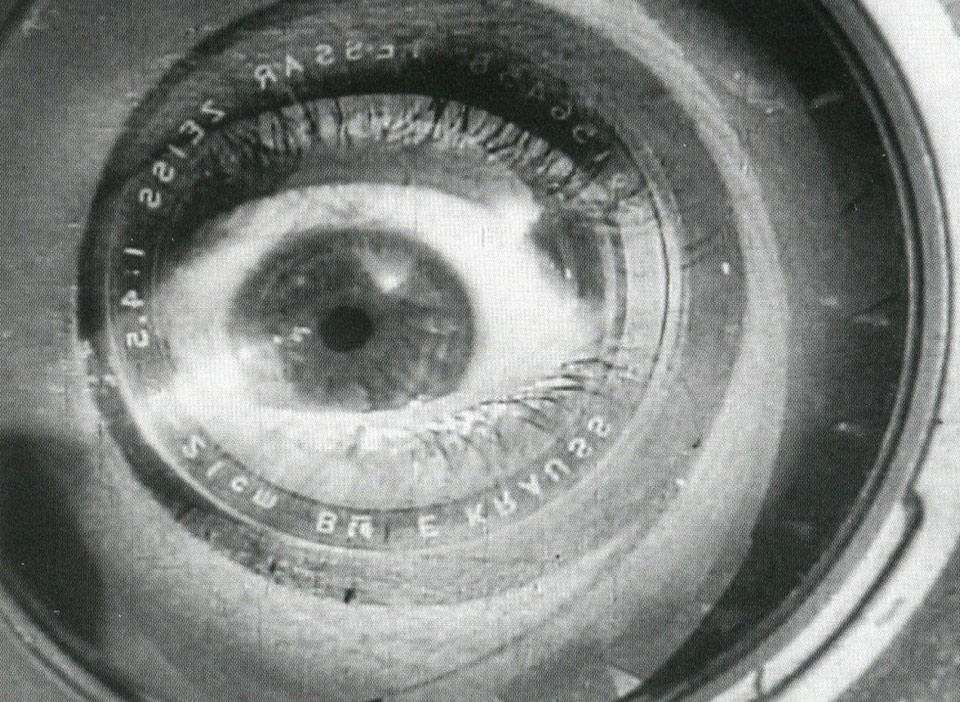

KH – Another amazing thing is that we have the entire portfolio of images from Larry Clark’s Tulsa. We are showing all 50 photographs of that landmark series. Clark’s images fit into one of the underlying threads of the exhibition: that photography is a socially engaged medium. This motif also plays out in another section in the show presenting photography about place. This section includes works by the Bechers, Edward Burtynsky, and Lewis Baltz–artists who are making records of changing landscapes. The final two sections feature pictures about performance and images that somehow make visible the fundamental materials and processes of photography. This final consideration of the properties of the medium itself includes photograms and pieces made through extended exposure times.

MAD – Have you ever had a moment in a museum or gallery, especially when you were younger, when you were absolutely struck by an image, or object and how you saw art, yourself, or the world was somehow changed? I ask because I had that experience myself when I was 21 on my first trip to Europe when I saw Francis Bacon’s triptych, Studies for Figures at the Base of the Crucifixion at the Tate Gallery in London. I was dumbstruck. I could not pull myself away from those paintings. I was staying in a youth hostel not far from the Tate and I visited almost daily – to this day I cannot say precisely what it was but it had something to do with the way he pictured grief as something wholly consuming so beyond words of comfort. I think experiences like that point to the vitality of galleries and museums, that seeing art in person is absolutely essential.

KH – There are two experiences that are conjured up by what you are describing. I’ll go with the most straightforward one first. I guess I was still in my early 20s, and I already knew that I was interested in contemporary art. I went to a show at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago called Negotiating Rapture which quite provocatively attempted to emphasize the spiritual in art by looking at 20th century artworks in the context of other artifacts. In the first or second room of the show there were a few of Ad Reinhart’s paintings. I had processed those paintings intellectually before but had never experienced them emotionally or truly visually. There was something about the pacing and ambiance of the exhibition that slowed me down, and I had a long and profound moment in front of those works. So all of sudden instead of looking at the paintings solely as something with art historical significance, I understood that wow, if you spend time in front of these objects your mind goes to really interesting places. That was a really important moment for me.

Another “revelatory” experience happened earlier when I was in college, studying abroad, and visited a Baroque church in Prague in which I was utterly surrounded by painting and sculpture. I am not a particularly religious person and I wouldn’t describe the experience as precisely religious but through the visual expressions gathered in one site and made by many different artists, one was truly transported to another place and time. I guess it was a transcendent moment for me, by entering that space and being immersed in that art-filled environment I was no longer part of the everyday world. Those were good moments.

MAD – Do you think part of the role of the curator to save things from being forgotten?

KH – In part, that was certainly a goal of the Anne Truitt show. About four or five years ago when I started thinking about the exhibition, the art world was reconsidering Minimalism. And except for a few noteworthy exceptions, Truitt’s work was not being included in the history that was being produced through exhibitions and publications. I thought it was an important responsibility, especially for an institution in Washington such as the Hirshhorn, to capture and present information about this artist before that ripe moment had passed. It was sad not to be able to work on the exhibition with Truitt before her death, and I could feel history slipping away as the generation of the artist’s contemporaries aged and passed on. Fortunately, I did get to speak to many people who knew her and I treasure their insights. On a personal level, there were moments with Truitt’s work that were reminiscent of my experiences with Ad Reinhart’s painting, and on the deepest level what attracted me to that project was that I felt that Truitt’s work is about the human condition.