Alejandro Cartagena

Alejandro Cartagena, from the project Americanos, 2013-2014. “These images are of Mexicans born legally in the USA. The project addresses subtle issues of border culture, the idea of still believing in an ‘American Dream’ and the possibilities of prosperity.”

Alejandro Cartagena, was born in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic in 1979, and now lives and works in Monterrey, Mexico. His projects employ landscape and portraiture as a means to examine social, urban and environmental issues. Cartagena’s work has been exhibited internationally in more than 50 group and individual exhibitions in spaces. Cartagena has self-published several award-winning titles including Santa Barbara Shame on US, A Guide to Infrastructure and Corruption, Rivers of Power, Before the War, and Carpoolers. He is represented by Kopeikin Gallery in Los Angeles.

This interview took place, via Skype, in January of 2018.

MAD: You were born in the Dominican Republic. When did you move to Mexico?

AC: My dad is Dominican; my mom is Mexican. Supported by their governments to study, young people from all over Latin American came to Monterrey to go to the Instituto Tecnologica, it’s like the MIT of Mexico. My dad and mom met in Monterrey and then had to go back to the Dominican Republic to work and pay off his debt. Eventually they came back in the 1990s.

MAD: Did you study photography as a student?

AC: No, I did not get into photography until I was 27. I did a Bachelor degree in Leisure Management (Laughter). I worked in the hotel industry, restaurants, and cultural centers. But to go back a bit, when we left the Dominican Republic, I was thirteen, and one day my parents said, “We are moving to Mexico.” I had no say in the matter. For a long time, the family photo albums of our life in the DR, were my refuge. The photographs grounded me somehow. I think subconsciously photography became a place where I could tell stories. When I decided that I didn’t want to work in hotels and restaurants anymore, I decided I wanted to do photography. So, I began taking workshops. I volunteered at a photography center for a year doing anything they asked me to do, scanning images, sweeping floors, carrying crates. They eventually offered me a job and I worked there for five years. That’s how I learned about photography, and not just how to take pictures, but how to write proposals, how to hang exhibitions. The center also has an archive of over 300,000 images, of historical, cultural, and political significance to Monterey. For three months, I was looking at family albums and scanning pictures to make a book about the history of Monterrey in terms of its people. That was my introduction to photography.

MAD: You have done several projects with appropriated imagery, sometimes combining your own pictures with found or archival images. While you are a prolific photographer yourself, it seems that the photographic archive, the culture, esthetics, and politics of the archive, is just as important to you as your own photographs to some extent.

AC: Absolutely, my studio is filled with boxes of other people’s images.

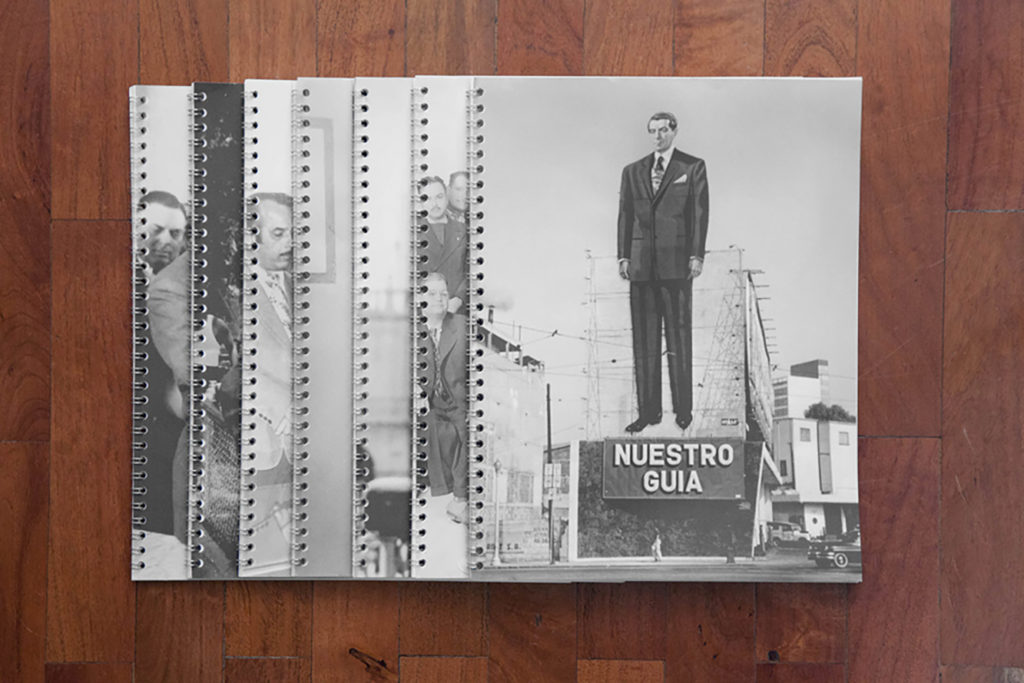

MAD: One of your book projects using archival imagery is called Love and Politics, which represents a part of Mexican history we don’t usually see. The images seem to be from the 1950s and 60s, people are elegantly dressed, doing various professional or ceremonial things. There is an emphasis on the display of bureaucratic male power in public spaces, for example.

AC: Yes, I am just finishing that, it’s ready to go to the printer this year. In this book, I go back to my old job to sift through the images I spent so many months scanning, images I could not let go of, that stuck in my mind. In addition to what you mention, another aspect of what I am interested in is the question of what does the government deem important to archive. Why were these moments important to keep in the memory of the city and state?

MAD: There are lots of pictures of men pointing at signs or plaques, it’s like a satire on redundancy or tautology. A building is named, usually after a man, then there is another man, some official of some sort, to inaugurate the building by pointing at the name, and then you have a photographer pointing his camera at the man pointing at the building. There an element of farce here. Many photographs with a singular purpose are so obvious they become fascinating and enigmatic, like surrealist puzzles.

AC: That’s where authorship comes in when it comes to the archive. It’s not about what is on the surface when you are selecting the imagery, if you can see them critically, you can begin to observe all the ways they speak collectively, and maybe unintentionally. I am not taking the pictures, but I am seeing things in the photographs that were not intentional.

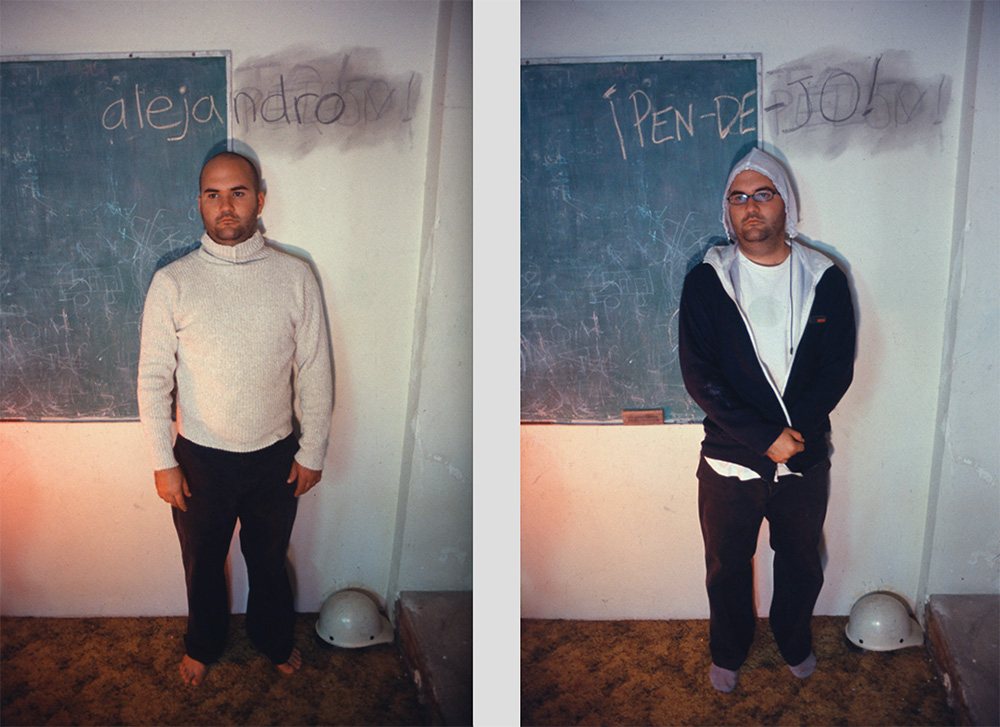

MAD: Let me ask you about a very early project, from 2004, it’s a series of self-portraits. You appear to be standing in a class room in front of a blackboard. In each picture, you are wearing different clothes and there is a different word or phrase written on the wall behind you – your name, then nationalities like Dominican and Mexican, but then the words become more insulting like ‘Pendejo’ – which means ‘stupid’ or ‘idiot.’ The series lit badly, there is something very obvious about them but they are also hilarious and heartbreaking.

AC: When I was first learning photography I loved the work of Jurgen Teller and this other German couple, the Blume’s….

MAD: Anna and Bernhard Blume, I love them! In fact, when I saw another early series of yours that appears to have been made in your childhood bedroom, I immediately thought of the Blume’s work.

AC: All my first works were self-portraits, I was thinking about the assumptions of the self, how I saw myself and how I imagined others saw me. I was performing myself for the camera. I couldn’t approach this idea except with irony and sarcasm. The images with the names written on the wall were about the things that I was called, names that people called me when I was a kid. There is another series from that time called The Masturbator. It was like I wanted to make fun of every assumption, I wanted to break the idea of self. And it worked, after I spent a year making these self-portraits, the inner part of me was done, I could begin to see outside of myself. I was then able to move on to make documentary work, landscapes and explore other ideas.

MAD: That is when you began a fairly massive project on Mexican suburbia that explores ideas of the middle class, home ownership, the banking system, how land is used or exploited to create certain illusions. The “American Dream’ seems to loom just outside the ideas explored here. One part of your project is series of photographs of these growing suburbs before they are occupied. Like some abandoned movie set, these perfect colorful, geometric neighborhoods, with mountains glowing in the distance are devoid of life.

AC: I am working on a book that will bring together all of the parts of that project. It started when I was working at the Photo Center and scanning images from a photographer who had documented life in and around Monterrey. He had made incredible landscape photographs of places that are now completely urbanized. So, I naively wanted to do what he did, to go re-photograph the places. I shot rolls and rolls of film, I liked color and the landscape but that was as sophisticated as it got. Wendy Watriss from PhotoFest was visiting to be a juror in a photo contest the Photography Center runs and I got to be her tour guide for three days and she asked to see my photos. She remarked on all the little houses in the landscape and said my work reminded her of the ‘New Topographics’ photographers in the 60s and 70s. I was taken aback, I hadn’t really seen what my photographs were revealing about the growth of the suburbs. It just clicked. I researched the history and cultural effects of suburbanization and began asking who lives there, who put those houses there, where did the money come from?

Many of these suburban communities that promised wealth and social progress through home ownership, which is the American model, have proved to be disastrous. People were convinced that to be a homeowner was the most important thing they could do. They got loans from the bank but the bank basically told them what neighborhood. So, they often live far from where they work, the communities are overpopulated and under served by police which has led to drug gangs taking over entire neighborhoods, which has led to the violence of the drug wars, which turned communities into war zones. Now there are more than two million houses that are empty or abandoned.

MAD: Your project Before the War is one of your most disturbing bodies of work. Although you don’t show any explicit violence, there is a sense of rising tension, as if people are living in a world where nothing can be trusted. There is a pall of fear that seems to hang over the project. And the way you have sequenced it is very cinematic.

AC: I began to think of all the work I had done up to this point as an archive. All the pictures in that series were taken right before the Drug War really broke out — 2005 through 2007. The drug gangs were already living in the neighborhoods and were operating in the peripheral areas of the small towns in the state of Monterrey. That is where I was photographing for the Suburbia project, the bad guys were there. But because no civilians were being killed yet, everything was quiet but there was a tension. In 2012, when I began thinking about what evidence of this might be in the photographs, and because I thought I was too familiar with my own images, I decided to contract an editor to go through my work and find the images that captured or evoked this feeling. I handed over the images and said “Here is my archive, look at it as if you found these images and you were told that there was a war brewing just below the surface of the images. The editor did what he wanted, he did not respect full-frame images, he cropped at will. If there was a small detail of a clock in a photograph that he thought signaled tension, he cropped everything else out. Now I always work with an editor on my projects, it brings another layer of awareness. We are so enamored with our own images that we sometimes cannot see what’s there.

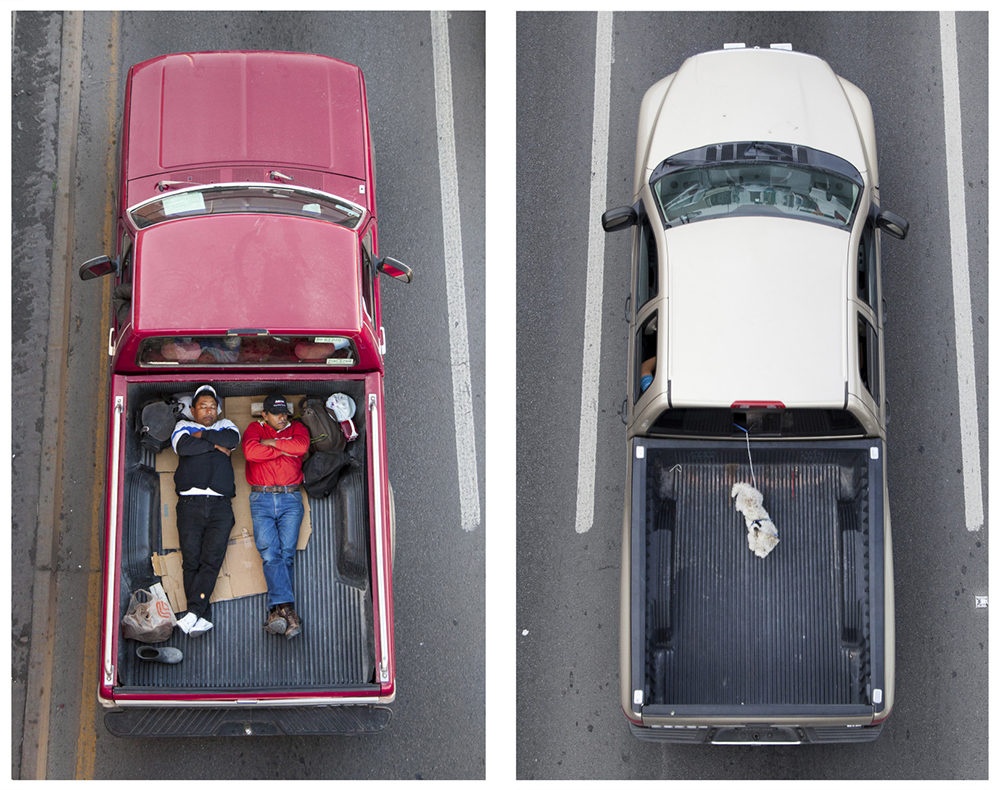

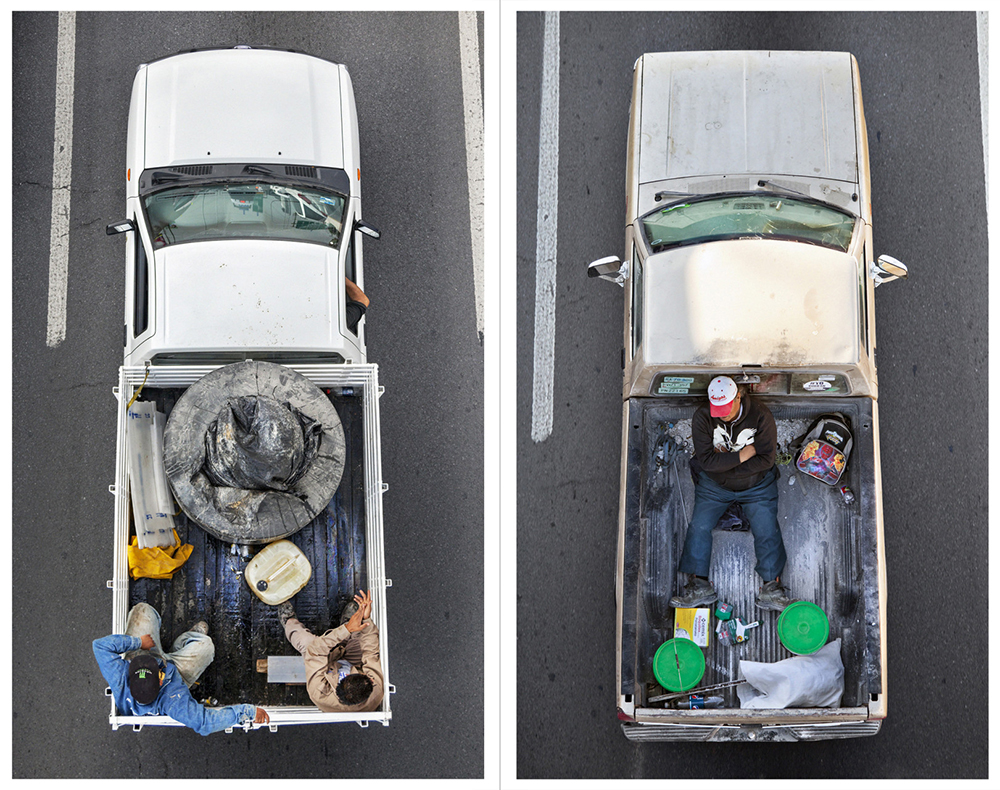

MAD: Carpoolers is your most well-known and celebrated project. How did it start? Did you have a revelation or epiphany while standing on an overpass watching cars pass below, seeing these guys sleeping in the backs of pick-up trucks and recognize that they embody so much of what the economy is?

AC: The ‘a-ha moment’ came three months after I started photographing the cars. I was commissioned to photographically respond to a series of research papers. The subject was the use of the car in metropolitan Monterrey. I rode with people, I photographed how they parked their cars, how they personalize their cars. One of the topics was traffic. We are generally not able to see traffic because we are in it. We don’t see how the landscape affects or creates traffic. So, I wanted to observe traffic from high vantage points. I was on one of those bridges looking down and began noticing all of these men in the backs of pickup trucks. I took a couple of photos and that was it. But three months later, after the commission was over, I kept thinking about them. I was skeptical if there was enough there, and I realized that I would probably have to shoot digital to make it work, although I always worked in medium and large-format analog. I was so insecure about it, I asked a former student of mine to come along.

But we went at the wrong time, because these guys are on their way to work, you really only see this between 7 and 9am. Again, some months passed and I went back again early in the morning, with my assistant because the drug war was in full force then, and I needed someone to keep a look-out, for security reasons. I shot maybe five that morning, went back to the studio to look at them on my computer and I realized that these guys, these images, connected different aspects of my Suburbia project. They were traveling from the distant working-class neighborhoods where they lived to work in the affluent suburbs that I had also photographed. The idea of homeownership, as witnessed by these workers going to the wealthy suburbs, was feeding the whole phenomenon. Photographing these men in the back of the trucks added another layer of complexity.

Aesthetically Carpoolers had nothing to do with my previous work in terms of tools, materials, and approach, but conceptually it tied it all together. I began going to the bridge two or three times a week. I played a little game with myself, because when I shoot film I only make one exposure of an image, I would do the same with digital, which is why it took me a year to make 120 pictures! (Laughter). They are zooming by! I try to see them coming from a distance as they approach the overpass, if I see that the front seat of the truck is full, there might be guys in the back so run over the other side of the bridge and align my camera. I took around 4000 images but only 120 are any good.

MAD: You decided to self-publish a book of the Carpoolers, why did you decide that was the way to get the images into the world?

AC: I approached established publishers, but they expected me to put up the money for them to publish my book. And I thought to myself “I am going to give you twenty-thousand dollars to publish my book and I am going to get fifty copies?” That doesn’t make any sense. I decided to risk it and self-publish. I had a bit of confidence that it would work because the pictures had gotten some attention already in newspapers and magazines. The images have a broad appeal, it’s not just the photo people who are interested. I did a pre-sale and sold 300 copies and at that point I realized it would be OK. I sold 1000 copies in two months. Bookstores approached me, museum bookshops approached me and then I realized I did not need a distributor and could self-publish.

MAD: You have spent a lot of time photographing at the border between Mexico and the United States.

AC: I was invited to the National Gallery of Canada to present the work in which I photograph the mother on one side of the border and the next day I photographed the daughter on the other side. They are like ghosts to one another. Every time I gave a gallery tour talking about those photographs, I was falling apart in tears telling the story of this divided family. They get to see each other maybe once a week, touching fingertips through the fence. I was a little bit embarrassed crying in front of people, but it shows that work that parallels your own situation in some way can really make you feel things deeply.

While I was photographing there, you would always see more people coming, one or two people from the U.S. side would make it up to the fence to meet whole families waiting to see them from the Mexican side. It is really difficult to get there on the U.S. side, there is no paved road and you have to go through the beach to get there. In Tijuana, it’s really easy to get there, you just drive up in your car.

MAD: That’s Friendship Park on the San Diego / Tijuana Border. It’s such an extraordinary border, it’s so dramatic geographically, politically, economically, and socially. As if the Third World could be restrained by a wall the First World has built. Lively and overcrowded neighborhoods press up to the wall, and on the other side, nothing but emptiness, except for border patrol agents.

AC: Exactly, in my pictures you can see an isolated border patrol agent on his four-wheeler going up a mountain while on the other side you can see all these neighborhoods pushing toward the wall. It’s as if the wall proclaims “You have to stop here. There’s space but we are not going to let you in.”

MAD: An old friend of mine, Michael Schnorr, who died a few years ago, was very involved in the politics of the border, and in fact was a founding member of the artist / activist group Border Arts Workshop. He lived in Imperial Beach and I would sometimes drive into Tijuana to watch as people gathered in the evening before attempting to cross the border. It is incredibly poignant and spooky to watch, in the gathering dusk, people ordering from food carts, chatting, gossiping, exchanging hugs and kisses and then moving one by one, or in small groups, toward the wall as it got dark. This dramatic and somewhat dangerous process is an everyday thing for many people. This was back in the 1990s, the situation is even more fraught, dangerous and extreme with this new regime in power in the U.S.

AC: It sounds like a scene from that movie Children of Men in which there is a place where people gather for a chance of a better life. Those people on the U.S. / Mexican border are not rapists and drug dealers, they are just trying to do what is best or necessary for their family. It is difficult to comprehend the amount of cultural propaganda that has been fed to them their whole lives about the superiority of life in the U.S. It’s in the fast food, the movies, the music, the products, the clothing, …

MAD: When I was traveling in Guatemala in 1989, most of the kids I met, if they went to school at all, were educated by evangelicals from the U.S. I went to a classroom in which the kids were drawing maps of the Americas, almost every version was like an upside-down triangle with Guatemala at the bottom and opening up to the U.S. at its widest. Like a cornucopia opening toward abundance, with virtually nothing south of where they were. The only promise was north.

AC: Yes, I have heard of schools in Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, teaching skills that will enable them to cross the border. Survival Skills! The cultural pressure is unstoppable.