Book Report #2 / Jim Goldberg’s Candy

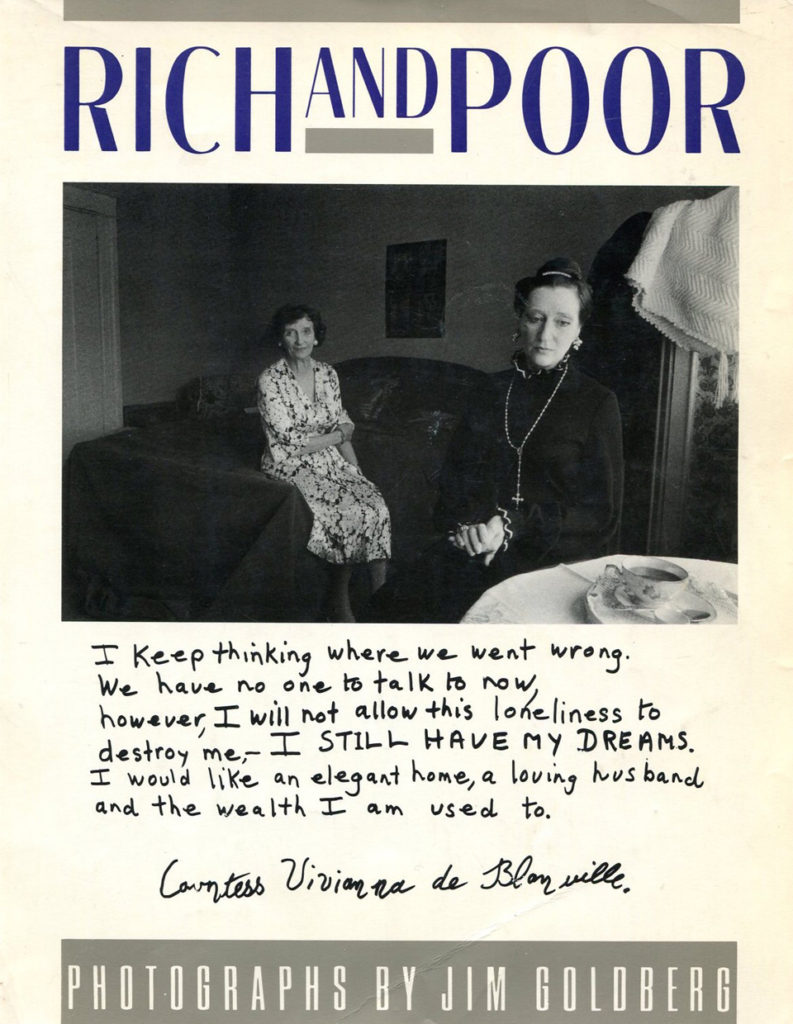

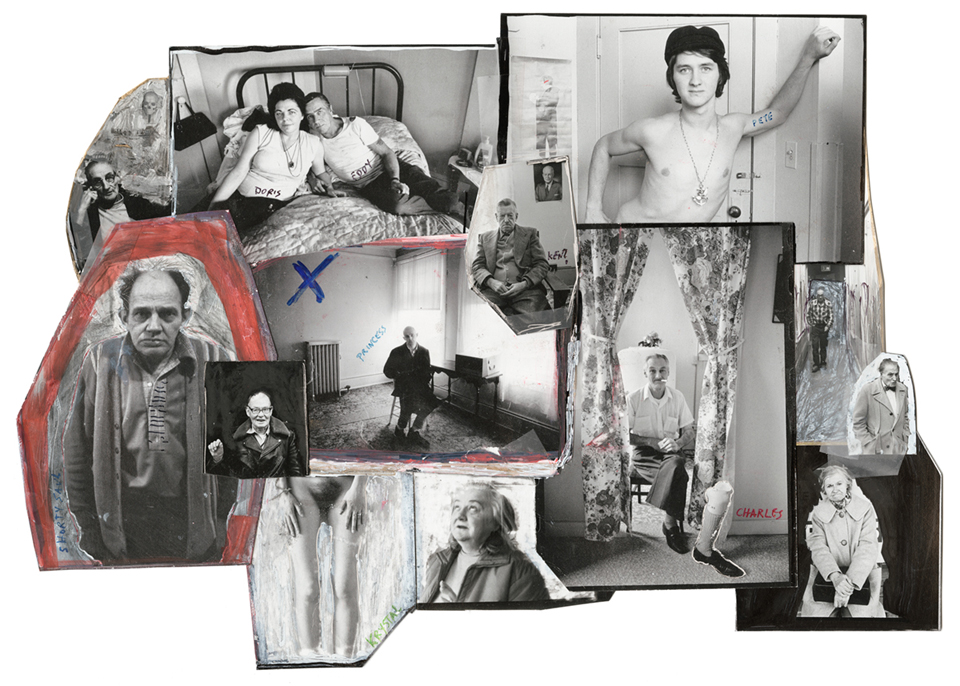

Jim Goldberg published his first book, Rich and Poor (Random House), in 1985. The concept and structure was straightforward — modest black and white photographic portraits of desperate or comfortable people appended by confessional inscriptions. Yet the book raised so many thorny questions about the limits, ethics and efficacy of documentary photography, among other things. It’s a simple thing, writing on a photograph, but the personal scrawls of Goldberg’s subjects interfered with the transparency of the photographic window, highlighting our often-unexamined assumptions about photographic objectivity. The portraits in Rich and Poor talked back, so to speak, responding to our rude gazes, sometimes with defensiveness or heartbreaking revelation. The handwritten inscriptions gave us a deeper glimpse into private doubts and the degrees of self-awareness these strangers who, in Goldberg’s project, carried the burden of representing two fundamental socioeconomic groups.

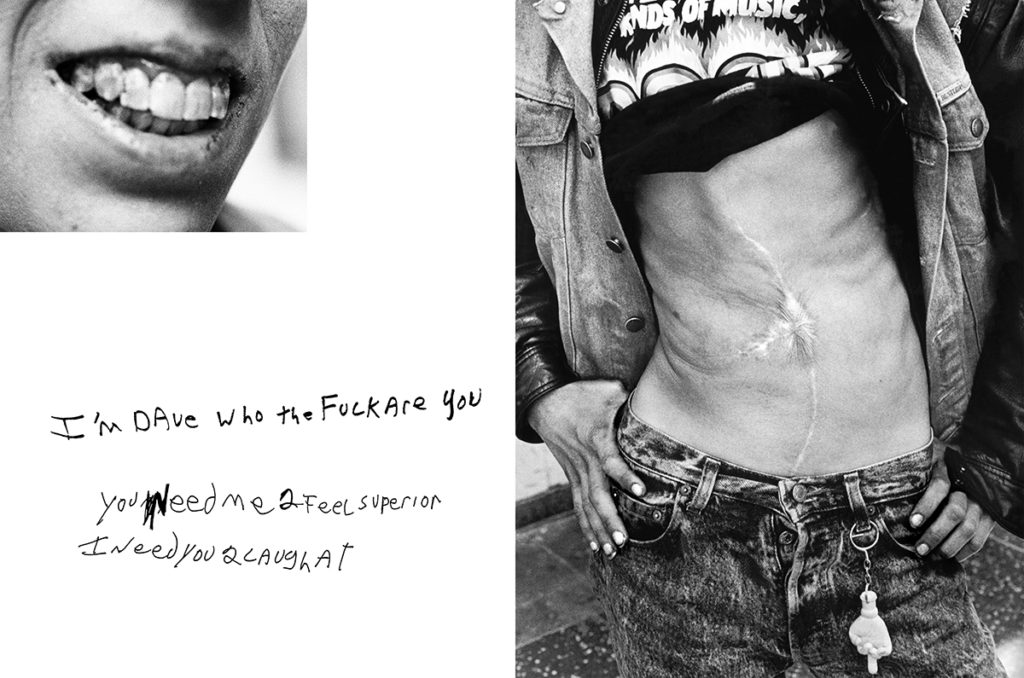

Ten years later, Goldberg released Raised by Wolves, an ambitious and raw documentary project on teenage runaways living on the streets of Los Angeles and San Francisco. Raised by Wolves weaves several personal narratives of these lost kids, especially of “Tweaky Dave” and “Echo.” Although Goldberg is self-described storyteller, he credits the curator Philip Brookman, with whom he worked on Raised by Wolves, with helping him to understand and undertake many of the new approaches to storytelling included in this critically acclaimed book. With Raised by Wolves, Goldberg’s long-term personal commitment to creating a broader picture led him to expand his improvisatory methods to include complex sequencing, ephemera, collage, voice recordings, video, and film stills. The related exhibition Raised by Wolves (1995) was groundbreaking in its gathering of these disparate elements into a lively, collage-like presentation. Although not completely unprecedented — Robert Frank’s Lines of my Hand (1972) for example, features collaged images, hand-written texts and film stills — it was Goldberg’s revitalization of the book form as a primary locus for reinventing documentary narrative that has most profoundly influenced a new generation of photographers.

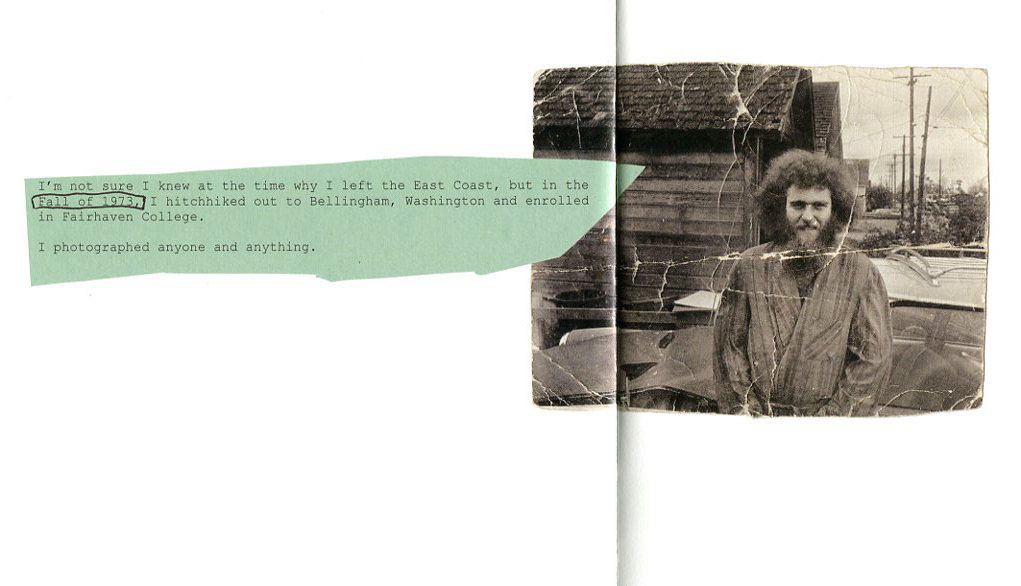

Recently, Goldberg published two new books, The Last Son (Super Labo, 2016) and Candy (Yale, 2017), published in tandem with Donovan Wylie’s book of photographs A Good and Spacious Land. Both of Goldberg’s new books explore the territory of personal memory as it intersects with issues of class distinctions and urban development in New Haven, Connecticut, where Goldberg was raised. The Last Son is more personal and smaller in scale, although it deals with many of the same subjects as Candy. To accompany the images in The Last Son, Goldberg wrote short, episodic texts that tell the story of his relationship to his parents and to New Haven, and of his first efforts as a photographer.

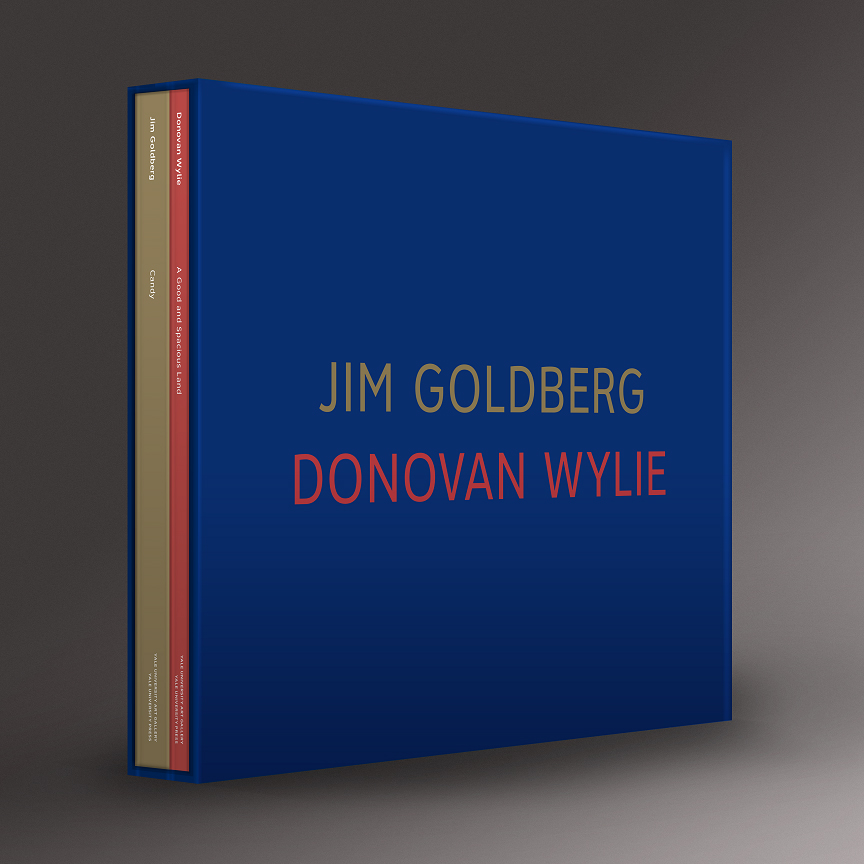

Goldberg sees these books, particularly Candy, as coming full circle, a return to the home he ran away from so many years ago. Candy was published by Yale University Press as part of a two-volume set alongside Wylie’s A Good and Spacious Land. Wylie and Goldberg’s double-effort is the result of a joint residency at the Yale University Art Gallery in 2013. Goldberg and the Irish-born Wylie share a deep friendship and mutual respect; both were members of Magnum during the residency, as well as participants in the experimental group project Postcards from America. In keeping with Goldberg’s collaborative ethos, the two photographers met regularly during their residency to share and discuss their photographs. While their styles and approaches to image making are quite divergent, together the two books create an extraordinary portrait of New Haven as a microcosm of the deep structural inequities that plague our country in general and our cities in particular. Both volumes feature poetic and rigorous texts by Christopher Klatell and Laura Wexler, respectively, and are presented together in a slipcase as a single tome.

Wylie turned his large-format camera on the reconstruction of the Interstate Highway System — a multi-year, multi-billion-dollar feat of civic engineering that rebuilt and rerouted I-91 and I-95 as they pass through and over New Haven — an infrastructure project so massive in scale it would make a certain Renaissance architect gasp in awe. But while Filippo Brunelleschi’s dome beautified Florence and ennobled its citizenry, the Interstate Highway System divides and destroys neighborhoods, and alienates the people who live in its shadow. Suggesting a kind of negative sublime, the humans in Wylie’s photographs seem to cower under the weight and monumentality of the concrete embankments and suspended bridges over which countless cars and trucks rapidly every day. The layout and presentation of the work within Wylie’s volume is as classic and measured as his large-format images.

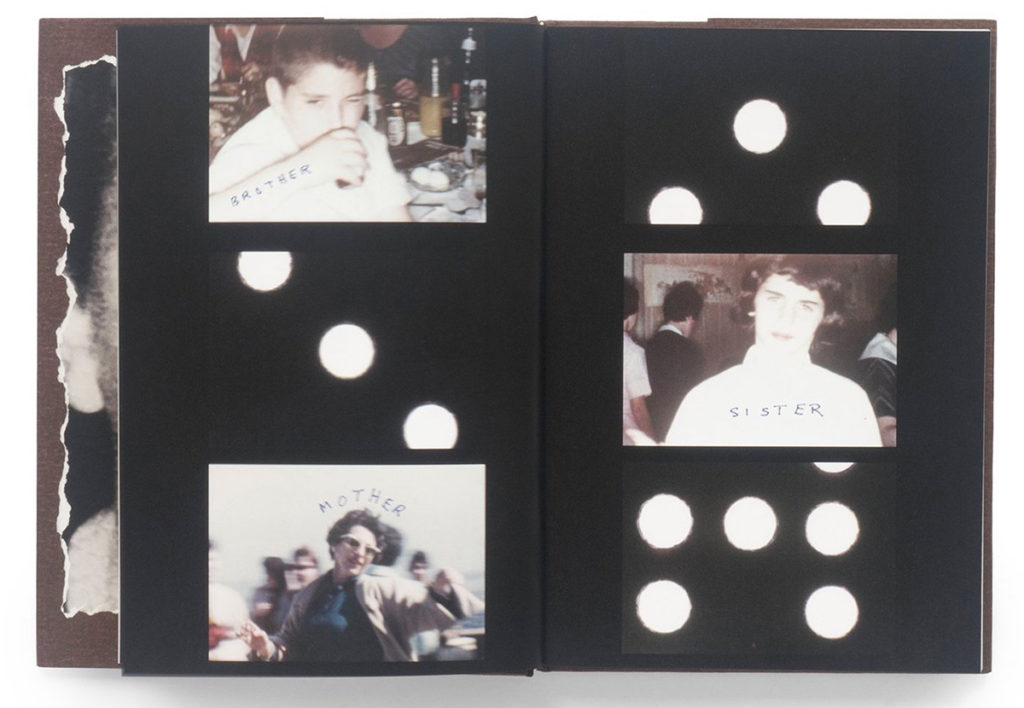

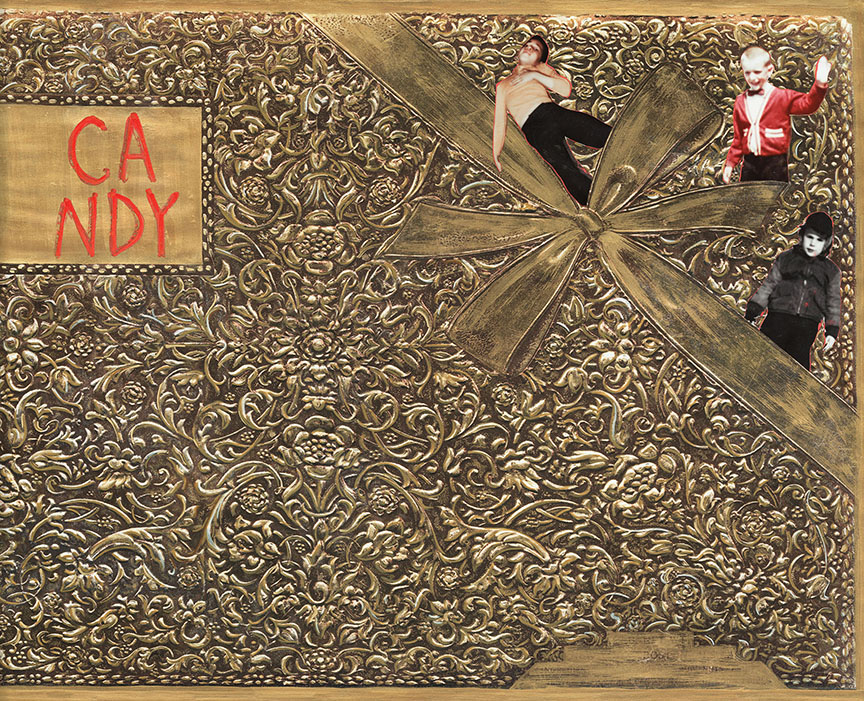

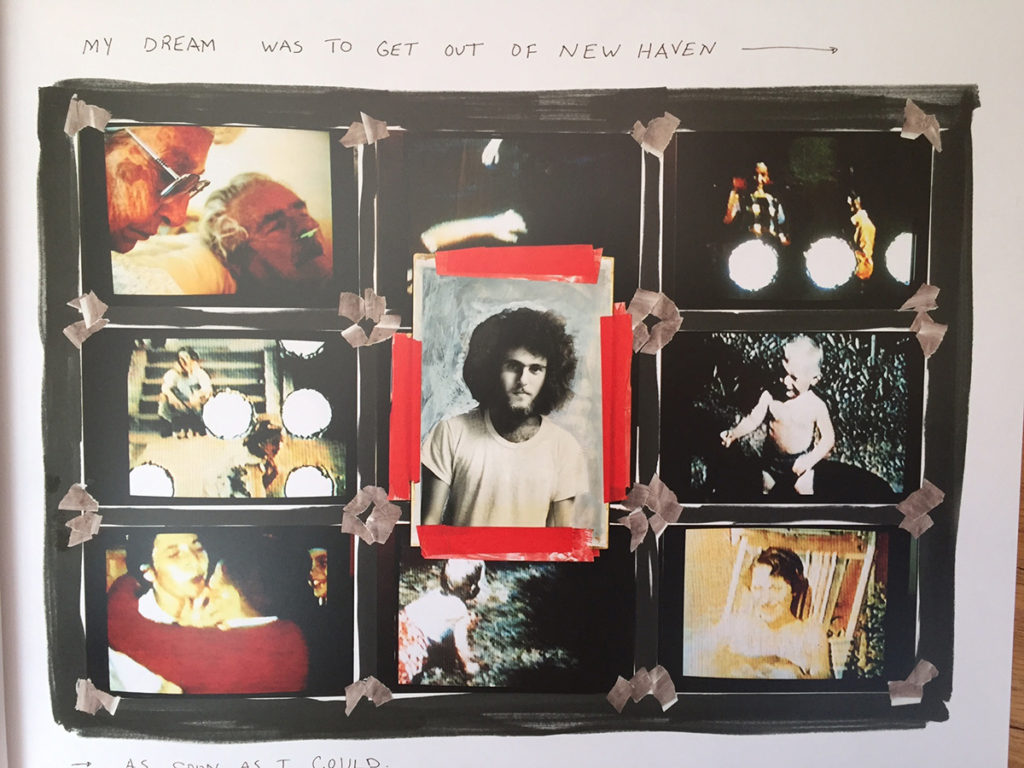

The front cover of Goldberg’s volume in the set replicates the sort of gold embossing reminiscent of an inexpensive box of chocolates one might purchase at the corner store for Mother’s Day; three of Goldberg’s childhood snapshots are tucked into the bow. In lieu of a guide to the types of chocolates inside the box, the back cover lists the names of New Haven’s neighborhoods. For many years, Goldberg’s parents owned and operated a candy store in New Haven called the Chauser Candy Company. The book is loosely organized in three sections or chapters; the first, Jim, describes in a fragmentary and cumulative manner, his parent’s history and how their dreams during the youthful years they ran the candy store coincided with and diverged from the civic hopes of the city. As Goldberg also relates in The Last Son, he escaped from his troubled New Haven upbringing by moving to San Francisco in his early twenties.

Goldberg did not want this project to represent his story alone, however; both he and Wylie were interested in the idea of the unfulfilled promise on personal and socio-economic terms. The other two sections of the book are extended portraits devoted to Germano Kimbro and Joe Taylor two local residents whose complicated biographies are rooted in New Haven. Germano is the son of Black Panthers member Warren Kimbro, whose activism in New Haven in the late 1960s was snuffed out when he was imprisoned in 1970. Germano’s life story after his father went to jail reveals the promise and disillusion of that revolutionary moment. The story of Joe — an avid collector of historical images of New Haven at times repurposed by Goldberg — continues the theme of family lineage; Joe’s father was blacklisted for being a member of the Communist Party.

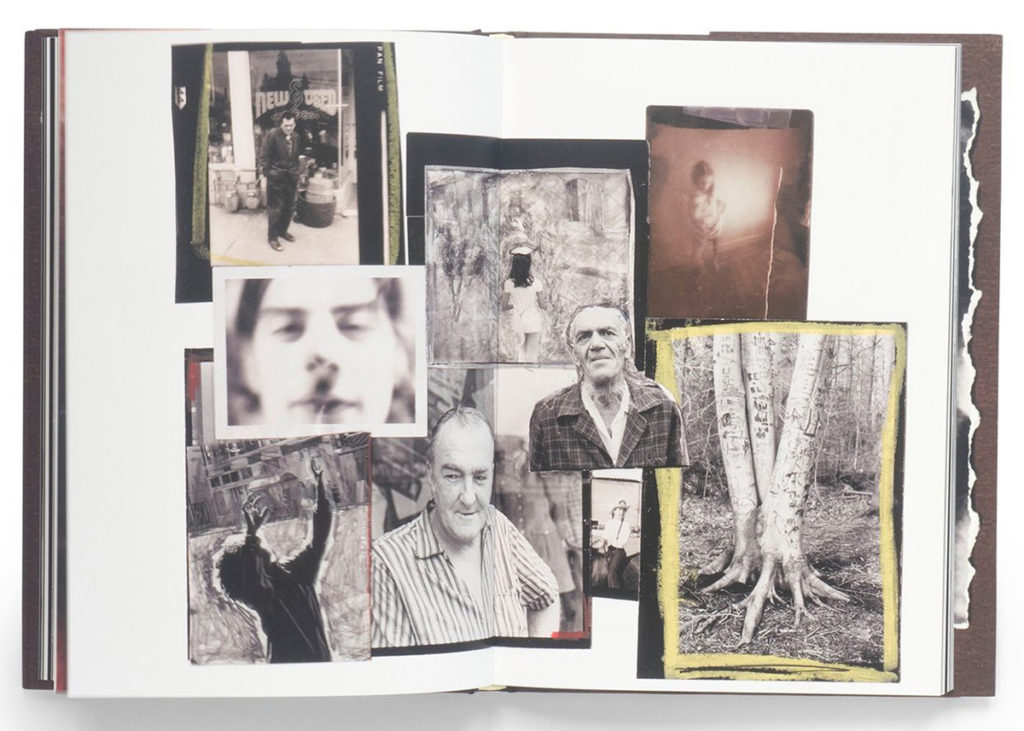

Candy is a substantial book — almost unwieldy in its size and weight — even without taking into account Wylie’s book. As with his earlier books, however, including The Last Son, Goldberg achieves an improvisatory physicality in the pages built from his parent’s snapshots, rough-hewn collages, film frames with holes punched out, photographs that Goldberg made as a teenager, images with cursive script scrawling across the frame, archival images of New Haven, and Goldberg’s contemporary portraits of New Haven citizens.

To this repertoire, Goldberg adds a new strategy — photographing while standing on the roof of a van or truck as it drives through the streets of the city. Embodying a DIY Google street view system, Goldberg announces himself, physically and verbally, calling out to passersby, trying to get their attention as he takes their picture. These sequences occupy double-page spreads throughout the book. The humor and absurdity of Goldberg’s performance is balanced, not only by the many wonderful photographs he captures, but also by his calling of attention to the growing corporate surveillance in our daily life. This visual density, consisting of layers of images and ephemera, creates a kind of sociological archeology that contains clues to overlapping narratives of civic hope and personal heartbreak.

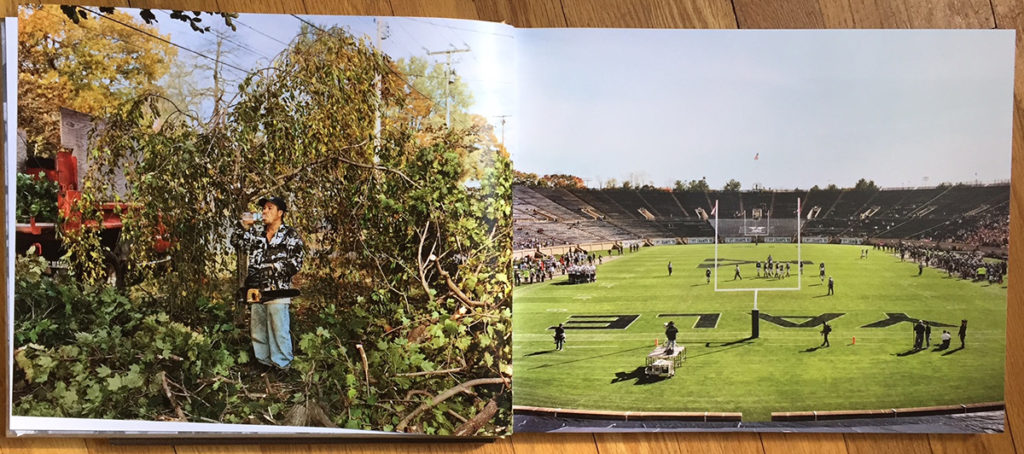

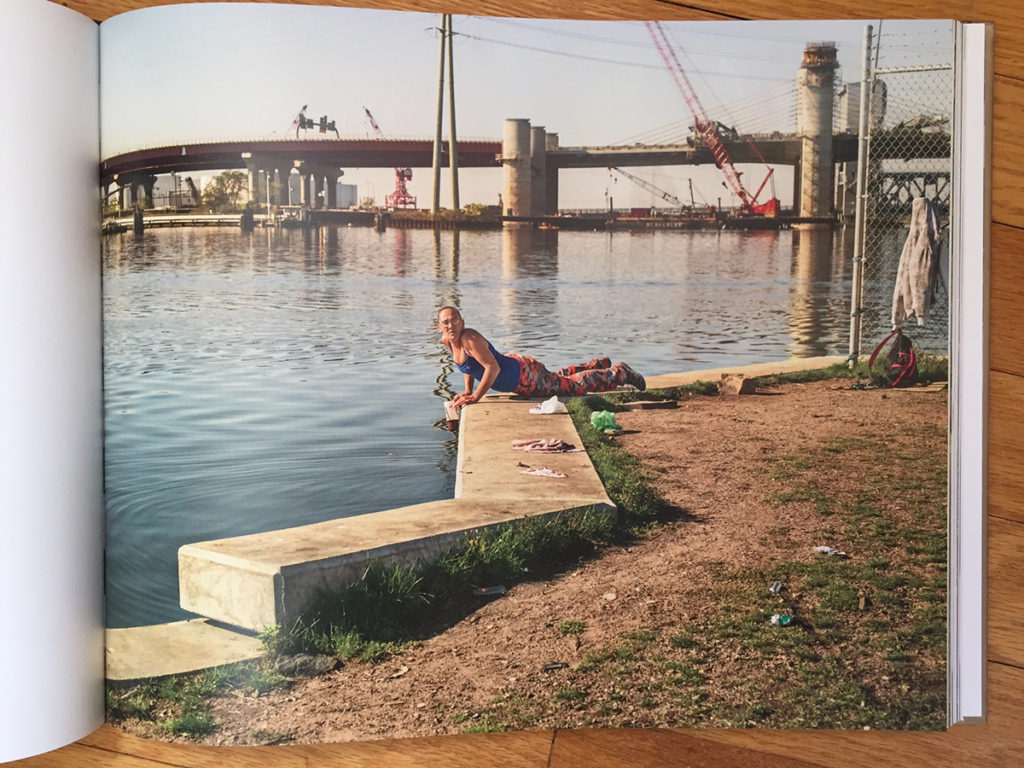

What sometimes gets lost in the discussion of Goldberg’s experiments with the documentary form is what a clear-eyed photographer he is. Among the collages, texts, and film stills are images of deeply felt psychological and political observation. One double-page spread early in the book shows a Latino gardener with a chainsaw in his hand standing amidst a thicket of downed branches. He is taking a swig from a water bottle with a faraway look in his eyes. The image on the right presents the carefully groomed Yale football stadium, its perfect green field glowing in late afternoon light. Turning the page and we observe two trim and shirtless college-age young men jogging past a tire store toward the camera. Later in the book, Goldberg observes a woman lying on the ground at the industrial edge of the city. She looks directly into the camera as she lowers her drinking cup into a river’s dark water. A backpack lays upon the ground and a hoodie hangs on a chain link fence, and echoing Wylie’s images, construction on the Interstate progresses in the distance. Interspersed among these acute observations are double-page collages of autumn leaves, old stone walls, and other signifiers of an Ivy League campus. Goldberg, like Wylie, does not directly implicate Yale — the institution is not the bad guy here, Yale funded this project after all — yet the juxtaposition, implied or direct, of privilege and opportunity with desperation and poverty, is unsettling.

The significance of the photographic book in the history of the medium is well established, particularly in the early years before photography was widely exhibited. Clearly Goldberg is not content with a traditional monograph; with each publication, he finds new strategies to expand our understanding of the book form — its materiality, intimacy, sequencing. That documentary photography exploits other people’s trauma is an earned if incomplete observation. Goldberg is an involved photographer, figuratively and literally. The physical — even performative — nature of his approach, particularly his books, embodies his commitment to counter faux-objectivity, and to telling complex and difficult stories while broadening, deepening, and personalizing what documentary photography can be.

This essay was originally published in Aperture’s Photobook Review #13. Thanks to Lesley Martin for the opportunity.