Gusdugger

Jared Ragland and Cary Norton, Bessemer Mounds, Jefferson County, Alabama, 2017.

The Bessemer Mounds were first occupied during the Late Woodland Period between 800-1000AD. The mounds were leveled sometime in the 1900’s; VisionLand, a defunct theme park, and a water sewage plant are now located on the site.

Jared Ragland and Cary Norton, Coosa River, Cherokee County, Alabama, 2017.

Near this point in the Coosa River, Pathkiller, the last king and full-blooded hereditary chief of the Cherokee, operated a ferry during the 19th century. After Pathkiller became too old to operate the ferry he spent his final days on the banks of the river, watching the water and river boats pass by. He was buried on the bluffs overlooking the Coosa, his body laid to rest facing the river.

Jared Ragland and Cary Norton, Near DeSoto Falls, DeKalb County, Alabama, 2017.

In June 1570, a small scouting group from Hernando DeSoto’s army of conquistadors made their way up Lookout Mountain to what is today known as DeSoto Falls, where they camped for at least two days and searched the area for gold and precious stones.

Jared Ragland and Cary Norton, Cahaba River, Dallas County, Alabama, 2017.

For millennia people have been drawn to the land situated at the confluence of the Cahaba and Alabama rivers. It was first occupied by large populations of Paleoindians; then from 1000-1500 the Mississippian period brought agriculture and mound builders. A walled city with palisades greeted Spanish explorers before western disease killed thousands in the 16th and 17th centuries. The remaining native peoples coalesced into four tribal nations – Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek – but were wiped out and forced to move by greater influx of Europeans. By the 19th century the dirt from the ancient mounds at Cahawba was used to build railroad beds, and the town became the first, yet quickly failed, capital of Alabama. A few short years later buildings and homes were taken down brick by brick and used to build Selma, home to further injustice.

Jared Ragland and Cary Norton, Garrett Cemetery, Cherokee County, Alabama, 2017.

Outside the gates of the Garrett Cemetery is the final resting place of Pathkiller, the last king and full-blooded hereditary chief of the Cherokee. During the American Revolution Pathkiller allied himself with the British and fought against American troops, but by 1813 had sided with Andrew Jackson’s militia in the Creek Wars. Just three years after Pathkiller’s death, Jackson forced the Cherokee from their ancestral homelands.

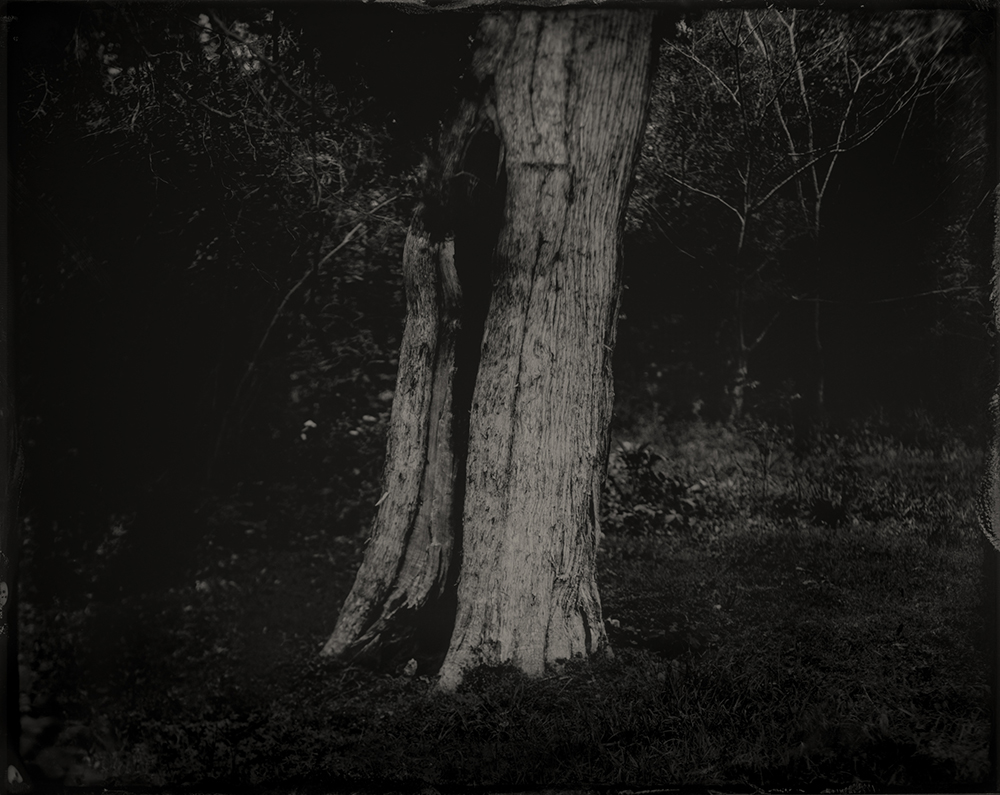

Jared Ragland and Cary Norton, Hollowed cedar tree at the entrance of Manitou Cave, outside of Fort Payne, Alabama, formerly Willstown, a Chickamauga settlement of the Cherokee nation, 2017.

Many Native American tribes attribute special spiritual significance to the cedar tree, calling it the “Tree of Life” or “Holy Tree.” In particular, the Cherokee, who inhabited Manitou (an Ojibwa word meaning, “spirit”) and the surrounding area, believed that cedar trees held the spirits of deceased ancestors and therefore possessed the power of protection. Inside the cave traces of human activity date back 10,000 years, including inscriptions from the Cherokee syllabary, invented by Sequoyah while he lived in Willstown. After the Cherokee removal on the Trail of Tears Manitou was used as a Confederate encampment and saltpeter mine; in the 1920s it was converted into a tourist destination where flappers danced the Charleston in a “ballroom” that featured electric lights; and during the Cold War it was outfitted as a fallout shelter. After decades of neglect the cave is the focus of grassroots historical and environmental protection and in 2016 was listed by the Alabama Trust for Historic Preservation as one of the state’s “places of peril.”

Jared Ragland and Cary Norton, Ohatchee, Calhoun County, Alabama, 2017.

Near this spot a marker stands memorializing the place where General Andrew Jackson found and adopted an orphaned Muscogee Creek baby in November, 1813. The story recounts how the baby was found in his dead mother’s arms and Jackson had such compassion that he took the child and raised him as his own. What the marker does not report is that it was also near this location that Jackson’s Tennessee militia began their genocide of the Red Stick Muscogee Creek Confederacy. The day before Jackson found the child, his forces trapped hundreds of Muscogee men, women and children inside their log homes and burned them alive. In his memoirs, Tennessee Volunteer Davy Crocket wrote that the few Creek who escaped were “shot down like dogs.” The ultimate defeat of the Red Sticks during the Creek War led to the loss of 23 million acres of ancestral land. The final treaty was dictated by Jackson, who after the conflict would be promoted to Major General and later become president. His portrait currently hangs near the Resolute Desk in Donald Trump’s Oval Office.

Where You Come From is Gone explores the importance of place, the passage of time, and the political dimensions of remembrance through the historical wet-plate collodion photographic process. Created on the eve of Alabama’s bicentennial, Ragland and Norton’s images seek to make known a history that has largely been eliminated and make visible the erasure that occurred in the American South between Hernando DeSoto’s first exploitation of native peoples in the 16th century and Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act 300 years later.

Using a 100-year-old field camera and a custom portable darkroom tailored to Ragland’s 4×4 truck, the two photographers journeyed more than 1,500 miles across 20 Alabama counties to locate, visit, and photograph indigenous sites. Yet the melancholy landscapes hold no obvious vestiges of the Native American cultures that once inhabited the sites; what one would hope to document, hope to preserve, hope to remember, is already gone. Instead, Ragland and Norton deliberately document absence and seek to render the often invisible layers of culture and civilization, creation and erasure, and the man-made and natural character of the landscape. The result is a body of landscape photographs in which the subject matter seems to exist outside of time, despite the fact that the project is explicitly about the passage of time, the slippage of memory, and the burying of history. While the relative emptiness of the landscapes elicits a sense of loss or absence, the beauty of the photographs conveys a continued sacrality of the space and puts viewers in touch with history and memory, helping us not only to imagine what may have been but also how best to honor what is, and what has been lost.

At this current moment in American life, the act of remembering is political and can have power, particularly when a polarizing president places a portrait of Andrew Jackson in the Oval Office and whose policies endanger the environment, dispute Native American land rights, and further disenfranchise marginalized citizens. In this way, Where You Come From is Gone works as a type of subtle activism by focusing on personal and collective memory-making. Through reasoned confrontation with our history and resistance toward (willful or accidental) cultural amnesia, these photographs provide a defense against the sort of ignorance that threatens democracy and enables totalitarianism and cautions us to be vigilant in guarding against altering, erasing, or “forgetting” our past.

Specializing in the 19th century wet-plate collodion tintype process and using vintage large format cameras, hand-crafted chemistry and a mobile darkroom, Jared Ragland and Cary Norton began documenting the people and landscapes of Alabama in 2016 under the collaborative name GUSDUGGER.

Jared Ragland is a fine art and documentary photographer and former White House photo editor. He is a 2017-2018 Alabama State Council on the Arts Media/Photography Fellow and currently teaches and coordinates exhibitions and community programs in the Department of Art and Art History at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. He is the photo editor of National Geographic Books’ “The President’s Photographer: Fifty Years Inside the Oval Office,” has worked on assignment for NGOs in the Balkans, the former Soviet Bloc, East Africa and Haiti, and in 2015 was named one of TIME Magazine’s “Instagram Photographers to Follow in All 50 States.” His photographs have been exhibited internationally and featured by The Oxford American and The New York Times. Jared is an alumnus of LaGrange College, and a 2003 graduate of Tulane University with an MFA in Photography. He resides in his hometown of Birmingham, Alabama.

Cary Norton is a fine art and editorial photographer, camera builder, and beekeeper. In 2009 he received worldwide recognition for building a 4×5” field camera from LEGO blocks, and he is currently at work constructing a custom 16×20” large format camera from locally-sourced lumber and iron. Cary has worked on long-term assignments in London and Baghdad and worked with NGOs in India, Kenya, and Uganda. In addition to client work for Ford Motor Co., Regions Bank, Verizon and Whole Foods Market, his photographs are in the collection of the Ogden Museum of Southern Art and have been published by Smithsonian Magazine, Southern Living, and The New York Times. Cary is an alumnus of Samford University, and he resides near his apiary in the Avondale neighborhood of Birmingham, Alabama with his wife Stephanie their two Dachshund rescues, Fin and Munch.

About the name GUSDUGGER: The Gus Dugger Saloon was a bar and tobacco shop located at 2114 1st Ave North in Birmingham during the 1880s. The upper floor of the two-story brick building was occupied by a photographer’s studio, and signage on the facade advertised landscaping, enlarging, and tintypes, as well as an art gallery.