Jessica Wimbley

Jessica Wimbley is an interdisciplinary artist living in Southern California. She attended Rhode Island School of Design for her undergraduate degree, earned an MFA at UC / Davis, and also completed an MA in Arts Management at Claremont Graduate University. Merging the genetic and biological with socio-historical concerns, Wimbley cites the poet Audre Lorde’s term biomythography to describe her strategy in representing and challenging the complexities of race and narrative in the American imagination. Employing painting, drawing, photography, collage, performance and digital tools, Wimbley allows herself to adapt and appropriate technologies and narratives to create works that are unmistakably contemporary yet layered with historical references.

This conversation took place via Skype on June 7, 2017.

MAD: When you were growing up your parents had an advertising agency, yes? Did that give you sensitivity to images? Were there discussions of images around the dinner table, for example?

JW: Yes, Some things that you take for granted, what you experience on a day-to-day basis, and for me we were always critiquing and contemplating and looking at media. We would look at commercials and analyze them. So there was always this kind of analytical type of conversation that surrounded media and popular culture that was just a natural part of the conversation of growing up in my household. Additionally my sister is an English professor who is also interested in the black arts movement and the visual culture. Conversations with my sister, and growing up and talking about how we were experiencing culture, visual culture, media, was something that we did a lot, at home. Yeah.

MAD: Being an artist isn’t just about making images it’s also about understanding how things are communicated, how images speak culturally.

JW: Being adult now and reflecting back and thinking back about the type of work that my parents did was the intersection between creating images for mass consumption and creating images to shift or push cultural norms. To target certain audiences, and the idea that you’re creating these images with a specific intent is something that’s very interesting to me. I could see the production of images that might have started around the conversation at a dinner table and end up being part of material culture, part of a collective history or a collective memory that people are consuming.

I went to art school in the late 90s/early 2000s — I started at RISD in 98 and graduated in 2003, so you’re talking about being in a space of transition between living in and working with the hardcopy / material image — and the digital. So there’s this literal kind of split that I’m interested in as an artist, in terms of doing collage and thinking about pulling from popular culture, and how that has changed between when my parents had their business and then my experience in art school and working as an artist after graduating from school.

MAD: So when did you get the first inkling that you were an artist?

JW: It was something, just ever since I was a little girl, it was just understood that ‘Jessie’s the artist,’ I would always be in the corner drawing or doing something like that. I was very fortunate that my public school from K-12 had a special arts program, so I had experienced this kind of specialized art education from first grade to sixth grade. My parents were very encouraging of me being an artist, especially my mom.

I also went to a lot of art camps, doing summer programs in the arts, so by the time I was in high school my mom would drive me on Saturdays to Milwaukee to take classes and at the Milwaukee Art Institute. I went to galleries and museums in Chicago with my mom who did an art history minor in college, so she was totally into art.

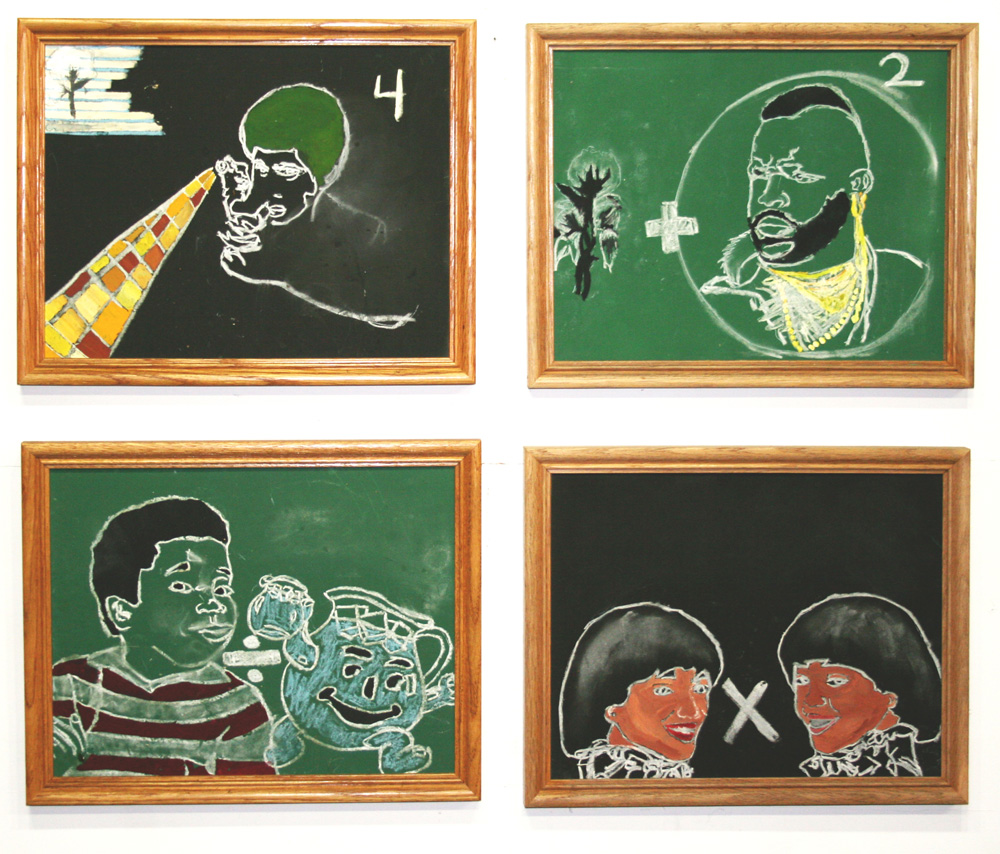

Jessica Wimbley, Chalkboard drawings, installation view, chalk and gouache on chalkboard, wood frame, 2007

MAD: Some of your earliest works you made while still an undergrad were chalk drawings on blackboard. They resemble pictographic equations, using images of African-Americans, or symbols associated with African-American history, for example Mr. T plus cotton, or Pam Grier and Urkel to the 7th power.

JW: (Laughs) I’m a dork!

MAD: They’re so funny and so smart and direct about the relationships between personal and collective history, popular culture and identification. Yet as you say, these are equations that cannot be solved. So can you talk about the genesis of that work?

JW: Sure. You know, it’s great, because I think it has literally taken this long for people to start getting this work. At the time, when I was doing it, people were like ‘what the hell is this? Why are you so into Urkel?’

MAD: Really?

JW: It’s interesting now to talk about it because I think it is also about getting a little bit older and understanding that the proliferation of the internet allows for some of these references to have a more integrated view point. But I got into that work thinking about how do we learn about images? How do we experience images and how do we put them together to create a sense of self and identity? I was thinking about images that are targeted towards black community. I think for me part of the issue was, what happens when you don’t feel reflected even when you’re supposedly targeted. Many of these images are composites, they’re not quite realistic representations. Some are based in reality, some in stereotype. And so you start creating a web, essentially, of these different images that you’re consuming and you have different ways in which this collective memory is informed. So I thought about breaking this down visually to understand how we create representation in media, and where do we pool these ideas from, and so conceptually an equation made a lot of sense to me.

MAD: Another early piece that I love is the Lawn Jockey performance photographs. How many did you do and how did you choose the sites? Were the gestures performed only for the camera?

JW: I thought about this statue / stereotype and putting a real person in this situation. Does it become ridiculous? What does it become? I didn’t ask permission to take these photo in front of anyone’s house, so were running in front of these different peoples houses in the middle of the street, and I’m dressed up as this lawn jockey. I worked with friend and artist Juliana Paciulli. We chose different kinds of homes, epic, classical architecture, or a typical middle-class home, and also what happens when you start going to storefronts and compose the image with different races. So I had about seven photos in that series. With the large house there’s actually a set of three images where I’m sitting at the stairs, then you see me running up the stairs, with the lantern, and then you see me in the action of like throwing the lantern through the window. So there’s an action sequence that happens within that. And we were using a large-format camera, which is contrary to doing it quickly.

MAD: You acknowledge the influence of Octavia Butler’s writing has had on your thinking and your work. Beginning in the 1970s Butler was one of the few black women claiming a space in the science fiction genre or speculative fiction, as some people like to call it. Contrary to what many people think science fiction isn’t only just about the technologically advanced future, the past can be just as important, which was true in Butler’s work, especially in her book Wild Seed, which takes place entirely in the past, in 17th century Africa, and antebellum America. I’m interested in this idea of reimagining the past with contemporary eyes…

JW: Yeah… me too (laughs)

Jessica Wimbley working on Belle Jet Sandi Mask 1, digital collage, graphite, pastel, charcoal on paper, detail, 2016

MAD: Yes, clearly. I have some specific questions, but can you talk very generally about that approach in your work?

JW: Questioning the grand narrative is a post-modernist gesture, and when I read Octavia Butler and the way that she really tries to address these narratives within kind of understanding history, I felt like I saw myself inserted into this greater kind of historical narrative. It’s important to have different eyes talking about the experience of culture, composing, creating culture in the past, especially within the Western world, because there’s been so much exclusion. There are so many stories to be told. So this idea of having different perspectives inform the interpretation and construction of history is a productive form of advocacy for inclusion, which I feel like art is supposed to help us do. Artists should be at the forefront of that. I often talk about my work in terms of these ideas of the micro and the macro, moving from the subjective to these notions to the objective, from personal history to collective history. I think if you move in between those spaces, you can create narratives that help build empathy, that can create connectivity, that can give you new insight into history, and how you experience the present. I really love looking at those elements and kind of weaving them together as a means to tell stories within my work, or address stories or narratives, or re-frame narratives.

MAD: Photography seems particularly well suited for meditations and reconsiderations of the past, as well as a way to examine how the past is represented. Your project Americana is multifaceted, including reworked stereographs from the 19th century. One is called Scouts, which I think is a Muybridge image of young native American men behind a pile a stones, and text on the card tells us its from the Modoc war, which was a native American rebellion in the early 1870s. Into the stereograph you digitally insert a character, and other images, in color, and can you talk about that image in particular, and that project as a whole?

JW: I wanted to think about my own cultural history in relationship to American history, how does that relationship change, how does it ebb and flow in terms of immigration for instance, within different family timelines. When does one become American? I had an interaction in SoCal with a Mexican-American woman in my Arts Management Program, where and I told her I care about diversity in the arts, and she replied, “ well if you care about that go back to Alabama – understand the culture.” This led me to start researching the story of Calafia, who is a fictional character from 16th century Spanish romantic literature that California is named after. I’m like OK so you have Garci Rodriguez de Montalvo from the 1500s who can imagine black women being in this space, but a contemporary Mexican-American woman of today cannot. This was amazing. So I fell into this hole imagining black women existing in this space that was projected to be where I currently live in California.

I began pulling images from stereographs, because I thought they were so culturally interesting and specific in terms of creating an American cultural identity and history through this new technology of photography. In some ways the images romanticized different groups of people and certainly didn’t tell complete stories. So I enjoyed reinserting different kinds of images that referenced different histories, linking digital technology with the stereograph. There are elements of performance when you insert a character into history, playing with notions of time, history, memory, past, present, and future. I enjoy conflating those spaces, and in the process thinking about what or who is an American?

MAD: In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, stereographs were part of most middle class homes. Images could be bought in series or themes, such as a trip down the Nile, scenes from Shakespeare or the Bible. They were also an influential form of ethnographic and anthropological information. In a lecture you gave you describe stereographs as being both entertainment and method for instructing how to view others. In that sense they often reinforced a colonial gaze and racist stereotypes. I have some stereographs that I want to show you, that I think you would enjoy (laughs).

JW: Yeah of course! Yay, I want to see! Show and tell!

MAD: I have a small collection of 19th c. photographs, daguerreotypes, tintypes, cabinet cards, and stereographs. As you suggest, these images can tell us a lot about both personal and cultural attitudes, and since stereographs were sold to a mass market, they give us a nice window into the cultural imagination. I have four to show you that I thought would be of interest to you.

MAD: Here is an idealized white girl holding bunny rabbits….

JW: Uh huh.

MAD: (Laughs) The photo was taken in Vermont by a photographer whose name is actually H.C. White (laughs).

JW: Wow.

MAD: Here is one of plantation workers in Florida, a pineapple plantation!

JW: What?! That’s amazing!

MAD: African American workers in a pineapple field in Florida, late 19th or early 20th c. I’m guessing.

JW: Wow.

MAD: Right? As you know often the back of the stereograph is printed with ‘factual’ information. So this text basically says it was hard work to pick pineapples and how these guys would wear leather gloves and that kind of thing. Of course it doesn’t say anything about poor working conditions and the slave wages. It is an exotic image, suggesting a hard but scenic life in a faraway land, but as you suggest, it also acts as a pedagogical device, instructing how to view others. Here is one of a Japanese baby floating upon a pile of silkworm cocoons — a sort of Orientalist thing, and again the text on the back talks about how the mother puts the baby down to rest while she is working her shift at the silk factory.

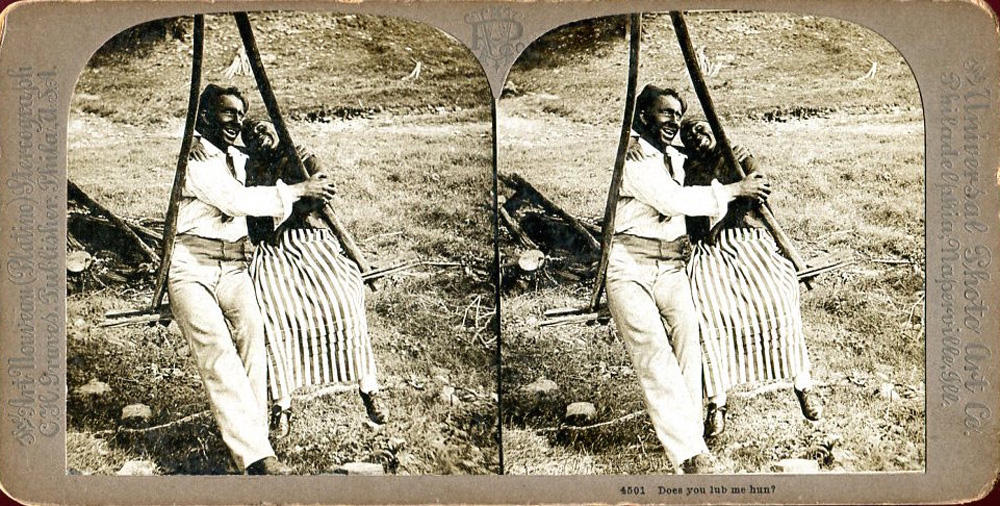

This last one this is a recent find, it’s sort of funny and appalling simultaneously. It’s two white actors in blackface, impersonating an African American couple sitting on a swing. There’s no text on the back but there is a caption that reads “Does you lub me, hun?”

JW: That’s crazy! I am also interested in cabinet cards. I’ve thought about them in relationship to how people are producing selfies. With cabinet cards people started to be the authors of their own portraiture in ways that weren’t available before. Before photography it was only the wealthy that had visual images of themselves. People were able to determine elements of identity —what you wanted to show about your identity. I love these types of layered stories that are within the object; I think that is something really interesting about the cabinet card and the stereograph. I just find it fascinating.

Jessica Wimbley, left, Belle 3, digital collage on canvas, 24 x 36.6 inches, 2013, right, Belle 10, digital collage on canvas, 35.5 x 54 inches, 2013

MAD: You also make these large-scale portraits that evoke 19th century cabinet cards, the images are dense with layers of images of yourself, and your ancestors. This layering suggests a kind of temporal simultaneity, as if the past is always with us, and it reminds me of this thing that Jimmie Durham observed. “I think there is no time, I think its a funny invention, there is a duration of things. If a piece of history doesn’t get resolved, its not history in the sense of historical conflicts, it’s the present. It’s always the present.” I was thinking about that quote in relationship to that series of yours.

JW: That’s so dope, because Jimmie Durham’s work is dope. I definitely believe that. It relates to this idea of sins of the father become the sins of the son, the idea that things don’t necessarily fully get resolved. So I am interested in this idea of creating the temporal, but it not being fixed with being able to interlace and layer different images of people from different time periods. Part of what I’m interested in is showing the collective within the individual, and the idea of multiple identities being present within a singular body and how that is constantly shifting, it’s not a fixed condition. By inserting my relatives I wanted to link the oral narrative I would hear from family, in particular my mother, about features of different family members and ways they might have looked or little physical nuances started to actually emerge. I was able to get an image of my grandmother and started putting together different relatives and I actually created my mom, and it was crazy! So I would have these surreal moments of creating layers including these different figures where I’m like oh snap! That’s my sister or what if this was the brother I never had, new potential people, possible relatives, begin to appear, suggesting different histories. It was a great discovery in making the work, to come across those things and see them happen in real time, in the making.

Jessica Wimbley, Flag, from I am Katrina series, digital collage on watercolor paper, 30 x 90 inches, 2011.

Jessica Wimbley, Their Ears were listening to god, from I am Katrina series, digital collage, C-print plexi mount, 24 x 48″, 2011

MAD: I want to ask you about I am Katrina, that features some of these strands you have been talking about, although you take them even further. There’s the past, the present, the future, the historic and the fictional, the metaphysical, the analog and the digital, the documentary and the performative. It’s a complex project, conceptually and pictorially. You use the Louisiana Creole legend of Marie Therese CoinCoin as a vehicle for your exploration. Can you riff on that a little bit?

JW: I met the artist and professor Fern Logan. I don’t know if you’re familiar with her work, but she’s and amazing photographer. She produced a book of her portraits series of black artists The Artist Portrait Series: Images of Contemporary African American Artists. We met at a conference and it was a love fest, and she invited me down to Cane River, which is a Creole town five hours outside of New Orleans. This was a year after Katrina. Marie CoinCoin is an important historic figure for Cane River. There are legends and myths about what she looked like. The story goes that she was this beautiful black slave woman that the French landowner fell in love with and when they married he freed her and their children. She became the owner of the plantation and then that’s how you had the largest run Creole plantation in Louisiana. So we have this female figure that is larger than life, the mother and patron saint of this community. But there is no imagery of her, basically just the oral history. So I thought it would be interesting to become this woman.

She was the most African figure within the lineage of this Creole community; because the interesting thing about being within this community is that you are talking about people who have a diverse range of features, many of them looked white. There is a color line that was there as well, so you have places were if you were darker than a paper bag you weren’t allowed in. So it was interesting to be in this place where there was this kind of reverence for this black woman, but there was discrimination and colorism as well.

I wasn’t sure how the community would take me, because I’m coming in and I do not look white at all. I look more like this woman that they don’t have visual representation of. I wanted to be respectful and mindful of the region’s history and culture and what was great is that they loved the project.

The South is amazing in that you can have this gorgeous super-romantic and lush landscape in conjunction with this horrific history. It puts you in this really interesting psychological space where you’re in love with the environment and the nature but there’s something rotten in the soil. Like there’s this underneath history amidst the plantations, old shacks, and the landscape where the sugarcane grew. The landscape is full of history and current events within the same plane. So I like the idea of creating the character of this black woman who is able to kind of be a participant, a witness, and observer of history, and composer of history.

MAD: She has incredible freedom; she’s both a part of history and outside of it.

JW: Yeah!

MAD: She is able to move, temporally and spatially, but yet she’s not otherworldly. She seems very human, she’s not a sprite or spirit that’s outside of humanity but is in fact of humanity, yet free of it, simultaneously.

JW: (claps) Yay! (laughs) Those are some of the things I’m going for within the work. It was important that the figure be able to move through history. I asked questions like, what does this figure wear? How am I represented? Where can I travel in these different times? I liked thinking about this idea of a universal African woman, which is what humanity comes from, right? Like if you’re going to represent something of humanity than nothing better than the black female body, since that’s what humanity came from. So it is this kind of general representation that isn’t hyper-sexualized, that isn’t stereotyped, but can function in the way exactly that you are explaining, moving through history, but is also a part of it, has agency, can step into it, can step out, can create it, can change it, and thinking about those temporal realities in relationship to these ideas of even going back to the interstellar and the origin of humanity.

Jessica Wimbley, left, collage with cabinet card and Ebony Magazine 1977, 4 x 6.375 inches, 2016, right, Cabinet Card with Hair, 4 x 6.375 inches, 2016

MAD: Lastly I wanted to ask you about the Cabinet Cards series. They are elegant and strange, these are the ones that you were actually physically intervening on the cabinet cards themselves — they evoke so many things from German Dadaist Hana Hoch, to…

JW: Oh, my gosh!

MAD: …to Victorian spirit photographs. But you are still addressing your themes of how history is represented. But one of the more obvious things about the cards is that you are physically intervening in the images, these are not digital manipulations, but you’re actually changing the original artifact. You destroy the original to create the new. Can you talk about that choice?

JW: It has been a really interesting process of going back and forth between the digital and the hand. I come from a painting background, so the idea of the hand is something that’s important to me in the sense of the hand is such an important part of making work and understanding work. When you’re working digitally and with photography it’s about the eye and the gaze. Can there be a digital hand? How do you integrate the two, and what happens when you start pulling from the historical mediums and combining them.

Within the Belle Jet series I am doing a lot of work with the hand on top of the actual digital print so it becomes very painterly, and part of that is going back and forth between doing the cabinet cards, and working in hand and then going digitally and working in hand, so this idea of the hand becomes something that’s really important. But specifically with the cabinet cards, what was a big breakthrough for me was divorcing myself from the preciousness of the object, and that physical intervention as something that you can use as a point of tension within the work. It’s so easy to find white people in cabinet cards. But because cabinet cards of people of color are so rare they are the most expensive. Like the stereographs images that you were showing me, there’s not a lot of representation of people of color but little white girls you can find anywhere. What freedom then do you have to go ahead and work into that history or work into that image? I’m also using Jet and Ebony magazines from the 70s, which have value as well, in terms of being historic materials. It also speaks to access to materials, the company that made Jet and Ebony magazine was Johnson Publishing. Johnson Publishing was bought and sold, and so you have this archive of black popular cultural images that are locked into a corporate entity that’s now owned by a totally different group of people. What happens to all these representations if you don’t have the hard copy and there’s a limited access to it digitally? So all these things start coming into play when you start putting them together and you’re not treating as precious untouchables— you are consuming and creating with them at the same time.