Oliver Wasow

Perhaps because he never studied photography formally, Oliver Wasow comes at the medium from a variety of angles — he collects vernacular photographs, digitally creates fantastical worlds, makes vivid portraits of friends and family, exhibits, curates, and teaches photography. He approaches the medium with enthusiasm and skepticism in equal measure. He has exhibited his work widely and was featured in Mia Fineman’s terrific show and catalog, Faking It: Manipulated Photography Before Photoshop at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. After many years of living in New York City, he now lives in upstate New York with his wife the artist Dana Hoey, their two children, and assorted animals.

This interview was conducted via Skype on October 10, 2016

MAD: You ran a gallery in the East Village in New York in the 1980s.

OW: Yes, the gallery was open from 1983 to 1987. I ran it with my friend Tom Brazleton. At first we were in a very small storefront on 7th Street and the gallery was called ‘Cash.’ We never considered that we would make any money, it didn’t seem to be in the realm of possibility, and then we began to make a bit of money. When people wrote us checks made out to ‘Cash’ it became a problem. So when we moved to a new space we decided to change our name and we became ‘Cash Newhouse.’ We wanted a corporate sounding name (in an ironic sense) and Newhouse was the name of a very well known art collector. We thought if used his name people might think he was backing our gallery. Although the more successful the gallery became the less fun it was. It was one of those ‘you don’t want to know how the sausage is made’ situations.

MAD: But it must have been interesting, you had some really terrific shows.

OW: There is no question that it was a valuable experience; I met a lot of great people. The problem was that I went into it as an artist and my own work suffered because I had to sublimate my own ego to work for others. That was difficult. And seeing the machinations of the art world was revealing in a bad way.

MAD: It seems like you went into the project with equal parts irony and altruism. To start a space like that is to provide a service, a platform for other artists.

OW: Yes, it was a much smaller world then, there weren’t nearly as many galleries as there are now. So yes, on the simplest level it was an opportunity to take matters in our own hands to circumvent a system that we had no access to anyway — and to show the work of artists we liked. It was an odd time in the art world, the Pictures Generation was still partially eclipsed by the Neo-Expressionist movement and what few galleries there were in the East Village were dominated by what you might call feigned angst or ghetto chic.

MAD: (Laughter) We should make a duo with those names, take it on tour – “Together Again- Feigned Angst and Ghetto Chic!” Can you talk a bit about some of the work you showed at the gallery?

OW: One of the earliest shows we did was with Allan McCollum and Jim Welling. It was the first opportunity I had to meet and work with artists that I admired, whose work I felt a strong connection to. I was a huge Jack Goldstein fan and we organized an exhibition of his work and a performance of his in a club in the East Village. We also did a show with Allen Ruppersberg that I liked a lot. Then we showed an artist that most people don’t know, Don Powley. I still really love Donald’s work, for me he is a real reminder that there are good artists out there who are not particularly ambitious, in the career sense, and fly under the radar. To this day he lives upstate with his wife Joan Nelson and their kids, and he makes strange, poetic work that he mostly shows to his friends. He is an example of the value of the unknown, which is an idea that runs through a lot of my projects.

MAD: The first work of yours that I am aware of is a series called ‘Hover’. But before we get to that I wanted to ask, what were you doing before Hover?

OW: I never went to art school. I studied in a Media Studies programs at Hunter College, which I chose because it was six blocks away from where I lived when I moved to New York in 1979. When I opened the gallery I was in grad school in the Media Studies program at the New School. I only did one year of that program and waited 20 years before I finished my Master’s Degree. So I did not study as an artist. My interest was in visual culture, media theory and photography. I was particularly interested in propaganda and science fiction. But I knew and lived with a number of artists and I was very involved in their world. I remember seeing Richard Prince’s work for the first time, in the basement of the old Metro Pictures, and it just jumped out at me.

I was playing around with video at the time and a bit of photography. My gallery partner Tom Brazleton and I organized a show called ‘Five and Dime’ in which we sat in the gallery making art, drawings, photos, collages, and just taped them on the wall. We sold the works for five, ten, or twenty-five dollars and we sold quite a bit of it. I liked the idea of making art that was cheap and accessible, not precious. Around that time I was interested in making images that bordered on abstraction, information without content. I was also interested in spectacle and kitsch.

MAD: Your Hover series is filled with images of UFOs, glowing orbs and other celestial phenomena. You made these images before Photoshop existed, did you achieve all those effects in the darkroom, a la Jerry Uelsmann?

OW: (Laughter) Jerry Uelsmann is the bane of my existence…..

MAD: Well, let me qualify that. I also went to art school before Photoshop so whenever anyone did anything remotely manipulative in the darkroom, people inevitably brought up Jerry Uelsmann; it was a kind of shorthand to describe otherworldly or surreal photo manipulations. I liked him when I was a teenager….

OW: He was the Salvador Dali of photography.

MAD: Yes, he was the poster boy for image manipulation. I look at his work and while I may admire the inventive technique, I have no interest in the images because they seem trite. So I don’t mean to compare your work in that way. I think your work operates on a kind of meta-scale in that while it evokes otherworldly phenomena, it does while simultaneously referring to pop culture and spectacle, in a Warholian way. It’s not about some private vision but more about the public imagination. Does that make sense?

OW: It delights me to hear you make the distinction because when one employs special effects and fantasy you flirt with kitsch. And the reason I laughed is that because the work is pre-digital, when people were mostly interested in the special effects quality of my work they brought up Uelsmann’s name. I have no interested in the content of Uelsmann’s work but where we do overlap is the hook of ‘Wow! What is that?’ Its also funny because while I have tried to distance myself from Uelsmann for years, Mia Fineman curated a show at the Met called ‘Photography before Photoshop’ in which there were practically 200 years worth of manipulated pre-digital photographs and of course my work was hung next to Jerry Uelsmann’s. (Laughter)

To get back to your question, so yes, the images were manipulated not in the darkroom but what I can only call ‘homemade special effects,’ often involving re-photographing something multiple times so the image resolution would break down and collaging things as seamlessly as I could. Seamlessness was the goal, seamlessness in order to seduce, it was important to me that it didn’t look like scissors and glue collage. I learned darkroom photography later in order to teach photography, years after I began exhibiting. I still find apertures and f-stops to be avoided if at all possible (Laughter). I am not a photographer in that sense.

MAD: I think this question applies to a lot of your work, but I will pose it specifically to Hover in which there are a lot of references to UFOs and other unexplained celestial phenomena. Were you interested in the philosophical aspects of that, by that I mean photography’s relationship to the murky boundaries between truth and fiction, or the narrative that these images implied, or were you interested in UFOs in particular?

OW: To some degree all of the above, but more the first two points although I cannot tell you how many times people ask me whether I believe in UFOs. I don’t believe in UFOs, I have no interest in UFOs specifically. But what I am interested in is the way a UFO photograph functions as a metaphor and represents the fictional aspects of photography. I am interested in the way they are offered as proof, they way they almost fight to escape the grainy-ness of the photography to reach a threshold of believability. But even more than that I am interested in the UFO as a metaphor for a hallucinatory spiritual experience.

Not to get too deep into it but I have an older brother who has chronic schizophrenia, and he has a very tenuous relationship with reality. He hallucinates a lot especially when I was younger, before he was medicated. During my adolescent years I was obsessed that I would also go crazy. That fear and obsession was exacerbated by my recreational drug use. So for me the space between fact and fiction as it manifests in the floating hallucinatory objects was, maybe not intentionally at the time but in retrospect, a metaphor or a visualization of that disconnect from reality where things are simultaneously beautiful but really scary at the same time. Which is the definition of the sublime.

I was less interested in the UFO as a trope of science fiction than I was in the floating object as metaphor for floating consciousness.

MAD: Speaking of floating objects, I know you have an obsession with the artist Roger Dean. You know a lot more about him than I do. He was an artist / illustrator who designed a lot of album covers for progressive rock bands in the 1970s and 80s. I listened to many of those bands when I was a teenager and I cannot look at Roger Dean’s imagery without immediately being keyed into this very specific sense memory of that feeling of just after you’ve taken LSD and you are not high yet but are waiting for it to kick in. I remember a giddy anticipation as I put the needle down into the groove of the Yes album Close to the Edge, which was going to be my soundtrack as I slid into the hallucinatory realm. Dean’s illustrations so perfectly imagined that float-y otherness.

OW: I had his posters all over my walls and I traveled into them. They were a comfortable escape for me as a teenager. And I still see art as doing that. My interest in Roger Dean as an adult has to do with a reconsideration of it as something I had let go of. At some point I decided that work was not serious, yet I was secretly still moved by it, maybe moved is not the right word, lets say still attracted to it. I am interested in why things get relegated to the realm of kitsch. I understand the limitations of Dean’s work that it is all affect, but that could be said of a lot of Baroque and Rococo art as well. I am interested in that line between serious art and kitsch.

MAD: I was going to ask you about kitsch later but since you brought it up. I see an interest in kitsch in almost the entirety of your work, not just in terms of garish colors or hokey motifs but almost in a political manner in the sense that kitsch is related to the vernacular and the democratic, a broad embrace of what visual culture is.

OW: In some ways it is more about the political aspects than the other qualities of kitsch. I want to give voice to those devalued esthetics. When I first moved to New York I worked in a gallery uptown and they always talked about the artists, not so much the artworks. I guess I was pretty naïve but I realized that for the art world the history of art was a history of names, where as for me it was a history of pictures. I don’t like artist biographies, I have a mistrust and a disdain for the mythologizing of the artist. Kitsch stands at the opposite end of the elitism in art, of the fetishizing of the value of the artist genius. I see the limitations of kitsch but I also see the value.

I now do a lot of work with vernacular images and I have to say that sometimes I see an image by an artist like Eggleston, and I don’t know immediately that it is an Eggleston and I think to myself, wow, what a great picture. So I know that there is a difference, I am a champion of the vernacular but I realize that there are people who are really gifted.

MAD: Well to acknowledge people who are good at something does not negate the democratic impulse. Kitsch is often a class-based denigration; museums are filled with aristocratic and bourgeois images that are tasteless or vulgar and yet are still venerated by the institution.

OW: I want to clarify that I am wary of an overly ironic relationship to kitsch. There is often a degree of mockery involved when contemporary artists engage with kitsch that I am not interested in. I mean, I try not to engage in mockery.

MAD: You followed the Hover project with a group of images you call ‘Buildings and Landscapes.’ I know some of that work but when I was reviewing it the other day I had a distinct mental picture of some Bulgarian surrealist living in some little village sending postcards to his friends in the outside world. There is something weirdly dystopian about them; they seem familiar, yet garish and foreign simultaneously, like he has grown up in an entirely different culture and political system. I guess what I am trying to say is that those pictures are not dystopian in the Hollywood sense of something like Blade Runner, they are less dramatic yet much stranger than that.

OW: I don’t know about Bulgarian, maybe Ukrainian (Laughter). At the time I was consciously interested in dystopic visions but also in the nature / culture binary. I grew up in Wisconsin around a lot of Frank Lloyd Wright architecture and I have always been conscious of the way buildings coexist with nature in a way that is sometimes harmonious and sometimes destructive. In the surrealist aspect of it, it is cinematic in the sense that I was attempting to marry a 19th century Hudson River School romanticism with a science fiction cinematic vision, if that makes sense.

MAD: But the cinematic is more Tarkovsky than Spielberg.

OW: Absolutely. I guess the current that runs through all of my work is a sense of unbalance, of things being slightly off. There may be surreal elements but I want it to be somewhat believable, a place a person can enter and exist in. Blade Runner was a big influence on me and a million other artists but I could never separate that influence from Hieronymus Bosch. I realize that the technological sublime has replaced the natural sublime in our culture but I am interested in how these two might coexist.

MAD: You began using digital tools in the early 90s.

OW: Yes, I bought a computer and learned Photoshop. It was a radical change in my work, not only in how I made it but also how people saw the work. So the suspension of disbelief was no longer a big part of experiencing the work and it also allowed me to indulge, for better or worse, my more baroque sensibilities to really explore the relationship between painting and photography, allowing me to get as hands on and manipulative with the images as I wanted to.

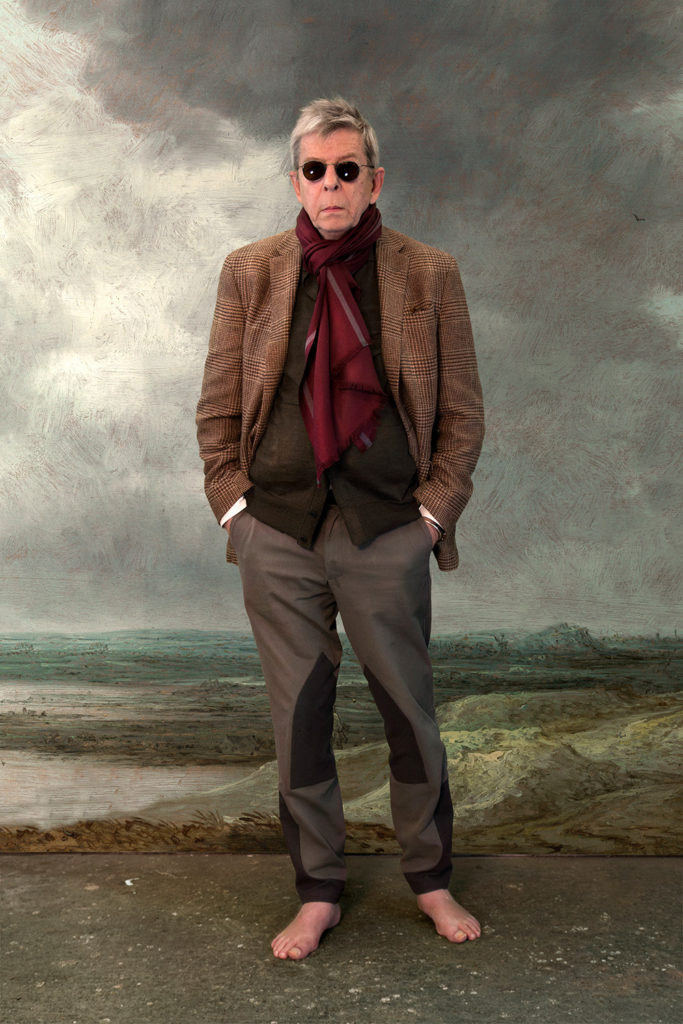

MAD: Lets talk about your most recent work – the portraits. The project began at home in your studio photographing your family and friends. Can you talk about how you came to that project? While I see connections with your older work, it is also a departure.

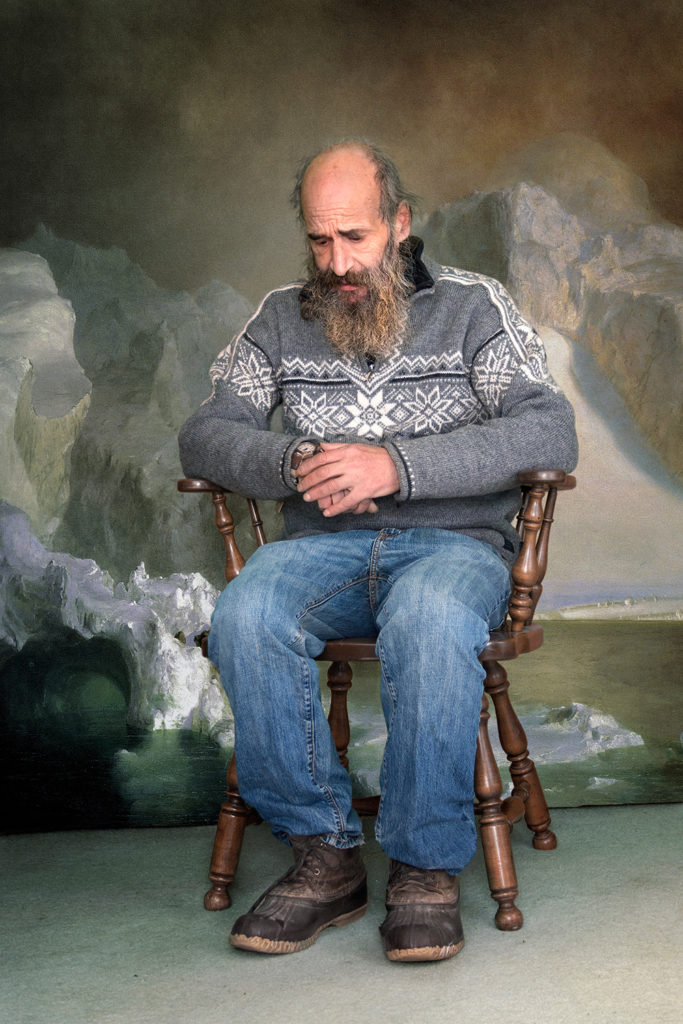

OW: I had never taken a picture of a person before, for my artwork that is, I have taken thousands of pictures of my children. The reason for that was that I told myself that people are too specific a sign of time and place. I was talking to a shrink once and he asked my why I never photographed people and I gave him my usual pseudo intellectual spiel and he was not convinced. I had a parallel activity at the time of collecting online vernacular photographs, snapshots of people. I was obsessed with images of people. I realized my position was ridiculous. I decided to bring more emotion to my photographs, to do something more direct and less distant. I have such a distrust of the emotional claims often afforded to photography but I wanted to be more genuine and emotional in my work. It was a battle for me. So I decided to jump right into that battle. The first two pictures I took were of my mother and my brother, who has schizophrenia. And it worked for me. For the first time I looked at one of my pictures and felt a deeper emotional connection.

I took those pictures in Wisconsin when I was visiting for Thanksgiving but most of the pictures I make here in Rhinebeck of friends and family. They are shot in front of a green screen and then I drop in landscapes that I have manipulated into the background.

MAD: The work references the history of portraiture in general but specifically, portraiture in photography especially in the 19th century when elaborate backdrops were employed as a way of connecting photography in painting through references to the picturesque.

OW: On the simplest level it is just a mash-up of photographic and painterly tropes that were used for 19th century carte-de-visite all the way up to the backdrops my kids choose for their school portraits. In most of those carte-de-visite images, the photographer did not make much of an effort to hide the painting; you can see the point where the painting meets the floor. I love that, there is something so sweet about the way the painting gathers, or pools behind the person. Like they were softening up the cold hard photography studio by placing the subject in a landscape.

MAD: So many things are going on where the painting meets the floor, between two and three dimensions, between photographic and painterly traditions, where different kinds of illusion meet. If you took a purely conceptual approach to making images that would be enough, I think I would even like it. I appreciate that is only one aspect of the work; it is essential, braided into the overall meaning of the work, but not the reason for embarking on such a project. You are making earnest images of people you are close to; they are anchored through an emotional connection, yet exist in a kind of fantasy space or constructed space. There is a lot going on yet they are relatively straightforward images. They are smart yet understated.

OW: That’s it in a nutshell and I’m happy to hear you say that. As I said, I aspired to make something that had some critical resonance but also satisfied something more mysterious and human, for a lack of a better way to put it.

MAD: I am reluctant to ask you this but I will ask and if it seems obtrusive we can strike it. I know a little bit of the backstory when I look at the picture of your brother, David. But even if I didn’t know, I think that I would still feel like it was a troubling portrait. There is a kind of burden in that image somehow. It has both a documentary affect and it communicates a deep level of compassion without glossing over anything. It feels very serious.

OW: It says all those things to me of course because it is my brother, other people have responded as you have and that makes me happy. I have a lot of trouble articulating this, but while I love Diane Arbus, I am suspect of the exploitative nature of photographing others in general but those who are unable to represent themselves, specifically. I want to avoid cheap pathos or mockery. I don’t know why but I felt like I could avoid that with my brother.

MAD: I have one more question for you, which has to do with your online life as a gatherer and presenter of vernacular photographs, an online curator really. You avidly, obsessively collect them and then organize them thematically. Many of these collections exist online but you also organized an exhibition and book of them titled ‘Artist Unknown.’

Many people are interested and are even collecting vernacular photography. The reasons are varied, snapshots are dislodged from narrative, people in them are often funny or dorky because of fashion or awkward poses, they have a kind of quaint charm. Many of the images you collect have those qualities but because you organize them in eccentric but somewhat rigorous themes, such as ‘Go over there by the TV’, the images become cultural studies. Changing photographic technologies, the history of gesture, shifts in fashion and self-presentation, the images become anthropological.

OW: Maybe what you just described is all that needs to be said about them but from a personal point of view, my initial interest was that it allowed me to engage with images without worrying about the things I worry about in my own work, such as nostalgia, kitsch and emotional manipulation. I have always been interested in collecting, archiving and indexing images. When I was young I used to spend hours in the New York Public Library going through their image collections. I was always fascinated by the way images were organized and categorized. So when the internet came along suddenly this finished archive started to get uploaded, and by that I mean analog photography is for the most part done, its over, people are not making analog pictures anymore. And even though there are millions, billions of them, 150 years worth, but its relatively small compared to the number of pictures that are made everyday on Instagram. So this era of analog photography is being rediscovered and uploaded to the internet. So it is an irresistible pull for me. It’s a social activity; there is the looking for them, posting them, discussing them online. The photograph becomes a verb and not a noun. Again, there is something democratic about it; I find snapshots that rival any great image from the history of photography.