The Collage Century

The twentieth century was the century of collage.

The process of breaking, fragmenting, and tearing images, objects, and concepts from their original or “natural” contexts and reassembling the disparate elements into new configurations is the most pervasive cultural practice. Why did this medium, most notably developed in Europe during the tumultuous decades between the two world wars, find its most fertile ground in American culture? Collage, once the sharp-edged weapon of revolutionary artists, has been entirely absorbed as one of the most common forms of image making. Every school child in art class learns to make collages before they can even write their own name. The radical “cut and paste” gesture of the early twentieth century is now a simple tool on our computer menu.

We are culturally (and maybe biologically) wired to try to put A and B together. We rely on relationships between things to know where we stand. Artists have long used this human predisposition toward literal meaning to confound viewer’s expectations. From Cubism to Dada, from Surrealism to Fluxus, from the cut-ups of Gysin and Burroughs to hypertext, twentieth century artists have sought to interrupt our preconceived notions of what constitutes pictorial and narrative logic, and collage in its various forms has been the dominant strategy. Did artists open the floodgates of collage until it influenced every aspect of popular culture or did they just recognize that collage would inevitably be the dominant characteristic of the twentieth century? Whether it was the chicken or the egg, what is obvious is that we are now fully immersed in collage culture.

At this point in history, it would be difficult to make a case for American cultural authenticity, being, as we are, a pastiche of peoples, traditions, and styles. Even the clothes we wear signal how much we mix and match. When we get up in the morning or go out at night, we may choose from a variety of different fashions that reference disparate stylistic decades. We wear our fashion with quotation marks; today hip-hugging bell-bottoms fraying at the cuffs, tonight perhaps a 1950s crooner a la Elvis, tomorrow a 1970s leisure suit, on the weekend, baggy hip-hop. We make no claim that anyone of these poses fully represents us. In fact, it is the pose itself, the shifting “personal assemblage,” if you will, that has come to symbolize our current freedom to cut and paste together our very identities.

An obvious example of our collage culture is the ubiquity of sampling in popular music. Early hip-hop pioneers used turntables to “scratch” from pre-existing records, riffing on old grooves and making new beats and contexts over which to rap. This was a kind of audio archeology, an unearthing of forgotten or resuscitating of too-familiar recordings. By selecting and repeating a fragment of the music, hip-hop collages various sound sources and styles to create entirely new musical structures. This is not a new phenomenon. Igor Stravinsky, for example, worked with the concept of collage, often inserting archaic Russian folk melodies into his twentieth century orchestrations. The French composer Erik Satie used the sounds of gunfire, typewriters, and various industrial crashes and bangs to literally interrupt his compositions. Again, what had been a strategy of early twentieth century avant-garde composers has now become as common as a 4/4 beat.

The Renaissance brought us its “window”; the revolution of single-point perspective in which a painting was constructed to give the impression that the viewer was seeing the subject perfectly framed from his own vantage point. The Renaissance window was radically different from previous medieval pictorial strategies in which the (usually holy) subject was represented as a two-dimensional icon or symbol-aloof, distant, figurative, yet almost abstract. Renaissance paintings, although idealized in many ways, were meant to mirror the world; a tree should look like a tree, a castle should appear to be a castle, a portrait should resemble its subject. Renaissance pictures showed people, places, and things in relation to one another; in other words, social and cultural meanings were stated through the relationships described within the frames. This method of picture construction became synonymous with what was to become commonly understood as the “beautiful” and the “natural.” Paintings reflected a burnished reality, composed in harmonious proportions, where everything and everyone were in their proper places. This ideal of pictorial harmony was to dominate artists’ practice for five centuries.

One can point to many cultural and technological shifts in the nineteenth century that prepared the ground for collage to become a radically new and ultimately pervasive phenomenon. The invention of photography freed painters from slavishly mimicking the external world, pointing them in the direction of the ephemeral, the internal, and the non-figurative. The ongoing Industrial Revolution shattered centuries-old social relations, creating burgeoning working classes alienated from their roots and their labor through wage slavery. Colonialism and immigration precipitated profound shifts in both personal and collective consciousness, bringing wildly divergent cultural practices, symbols, and languages in close proximity to one another. Cities became collage-like in their random juxtapositions of architecture, ethnicity, wealth, and poverty. Strolling through the alleys and boulevards of any major nineteenth century European or American city, one would encounter dozens of languages being spoken in a grand linguistic collage. The simultaneous and fragmented narratives that played out on the street, as the multitudes negotiated their lives, were a constant reminder that the city was a shifting hybrid always in flux.

The very recognition of hybridity as a cultural paradigm was and is, in essence, a challenge to those who hold on to the idea of a natural seamlessness to truth, narrative, and beauty. The Renaissance window is shattered by collage. Constructed out of bits and pieces, the detritus of daily life, the collage is a kind of violation of notions of the eternal; it is temporary and un-precious. The collage is a two-dimensional analog to what was happening in three dimensions on the streets. Some artists resisted this chaos, this “bastardization” of the arts and fervently protected the hallowed halls of “classical” or “timeless” beauty. Certainly, politicians and demagogues of a certain stripe also feared the shifting nature of collage culture, making the calls to national purity one of the more extreme responses to the phenomenon of cultural realignment.

Collage also suggests a new way of making meaning; the seemingly seamless images and narratives that represent history, culture, and ideology are implicitly and explicitly challenged by collage. The heroic effort to create a masterpiece in oil on canvas, for example, was mocked and made irrelevant by a few bits of torn paper. Exposed as elaborate theatrical spectacles, the unviolated surfaces of traditional paintings served to gloss over the contradictions and complexities of history. The hierarchies of art practice and value were questioned by the humble gesture of suturing together previously unrelated images. The humble replaced the heroic, the epic overshadowed by the quotidian. The use of commonplace images bits of advertising, a used train ticket, an old carte-de-visite, combined and re-contextualized pictorial space and suggested that similar shifts were possible in social space.

As European colonial empires began to sag, fracture, and strain under the pressure of independence movements and more black and brown bodies began appearing on the streets of European capitals, the very notion of “whiteness” as an index of normality began to come under scrutiny. In addition to a rising population of Third World citizens, cultural artifacts acquired from the far-flung reaches of the globe were put on public display in world expositions and ethnographic museums, creating a kind of cultural dissonance, sparking a “primitivist” craze that swept Europe and manifesting itself in many forms in art, literature, and music. African masks, Tahitian motifs, an obsession with American Indians, and the jazz and ragtime of Black America, fueled fads in fashion, music, art and literature. The Dadaists were not immune to these trends. Oftentimes the “nonsense” lyrics of poems and songs were brutish mockeries of tribal languages. As if to free themselves from the constraints of civilization, the Dadaists could harness the supposed mystical power of “primitive” utterances.

We must destroy the so-called nobility, wholly literary and traditional, of marble and bronze: and we must firmly deny the law that a sculptural ensemble must be made exclusively from one single material. The sculptor may use twenty or more different materials if he likes ... provided that the plastic emotion requires it … glass, wood, cardboard, iron, cement, hair, leather, cloth, mirrors, electric lights, etc …

~Umberto Boccioni

Depending on the specific context and the artist’s intent, collage became a kind of rhetorical weapon in the service of a wide array of esthetics and ideologies. For the Italian Futurists, collage was ideally suited to illustrate their obsessions with the characteristics of the new century, the era of the machine: Speed, fragmentation, multiple realities, and repetition became a way to negate the precious traditions of the past. The Futurists embraced collage in all forms of expression ~ poetry, sound, painting, performance, and music. The fetishizing of the machine, an emphasis on the violence of creation, and the total negation of humanist thought led many of the Italian Futurists toward the politics of fascism. Ironically, fascism demanded a recapitulation of what it deemed the “decadent” avant-garde ideas of the Futurists. Ultimately in Italy, the noisy, chaotic, and subversive nihilism of Futurism was suppressed in favor of a propagandistic realism, forcing a retreat to classical wholeness.

Yet, the Futurists’ seed was sown far and wide, with its ideas shifting, evolving, and mutating in various cities in Europe and America. The early twentieth century revolutions in politics, philosophies, and esthetics found no more fertile soil than that in Russia. The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 fueled a utopian and utilitarian revolution in the arts, transforming the role of the artist from the bourgeois provocateur to artist as cultural worker, laboring not against the state but in the service of socialist idealism. Photomontage became the most potent medium for communicating the revolutionary message that this was a new century in every way imaginable. Combining photographs and text with bold colors and designs, photomontage could speak energetically and directly to a largely illiterate population. Alexander Rodchenko and Gustav Klutsis are just two of the most renowned practitioners of photomontage who utilized posters, newspapers, magazines, and book covers to speak to the masses with a messianic fervor.

Our whole purpose was to integrate objects from the world of machines and industry in the world of art.

~Hannah Hoch

In 1916, when Johnny Heartfield and I invented photomontage in my studio at the south end of town at 5 o’clock one May morning, we had no idea of the immense possibilities, or the thorny but successful career that awaited the new invention. On a piece of cardboard we pasted a mishmash of advertisements for hernia belts, student song books and dog food, labels from schnapps and wine bottles, and photographs from picture papers, cut up at will in such a way as to say, in pictures, what would have been banned by the censors if we had said it in words. ~George Grosz

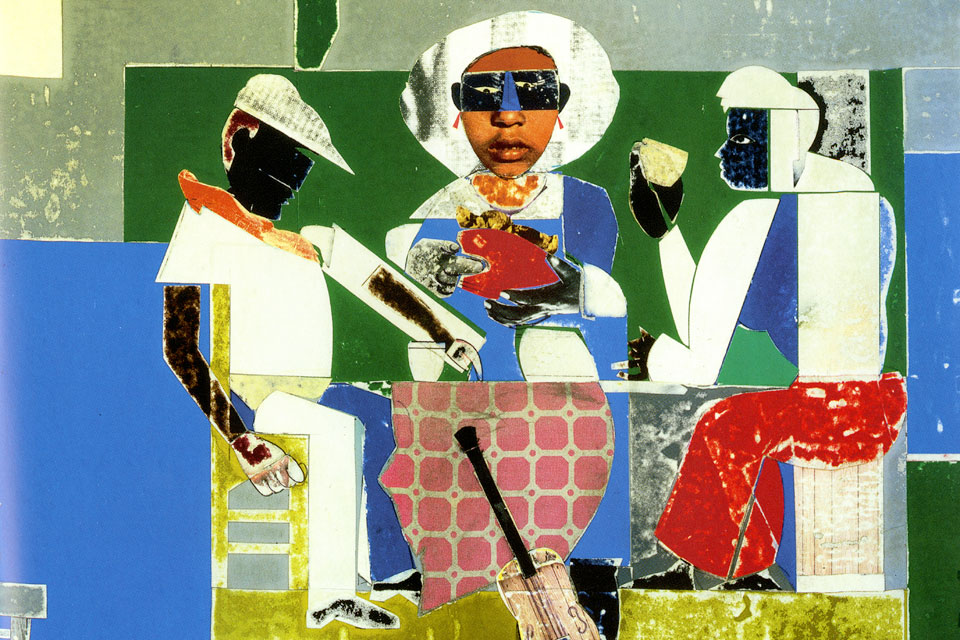

Initially, in the hands of the artists of the German Weimar Republic such as John Heartfield, George Grosz, and Hannah Hoch, the collage served the Dada agenda, which was to undermine tradition by celebrating the chaotic energy of nonsense. But increasingly by the early 1920s their works in collage and photomontage served as an index of the violence of recent German history and an indictment of the rising power of Nazism. Hoch assembled her iconic images from diverse sources: fashion magazines, art history texts, ethnographic travelogues, illustrated how-to books, et cetera. Her figures are truncated, misshapen, disfigured, funny, and horrific, upturning the primitive/civilized binary that was the underpinning of European self-definition. By suggesting that identity itself was a kind of collage and mocking the very notions of cultural purity that the National Socialists so desired to establish, Hoch’s images represented all that the fascists hated about modern culture ~ fragmentation , hybridity, gender confusion, race mixing, and moral relativism.

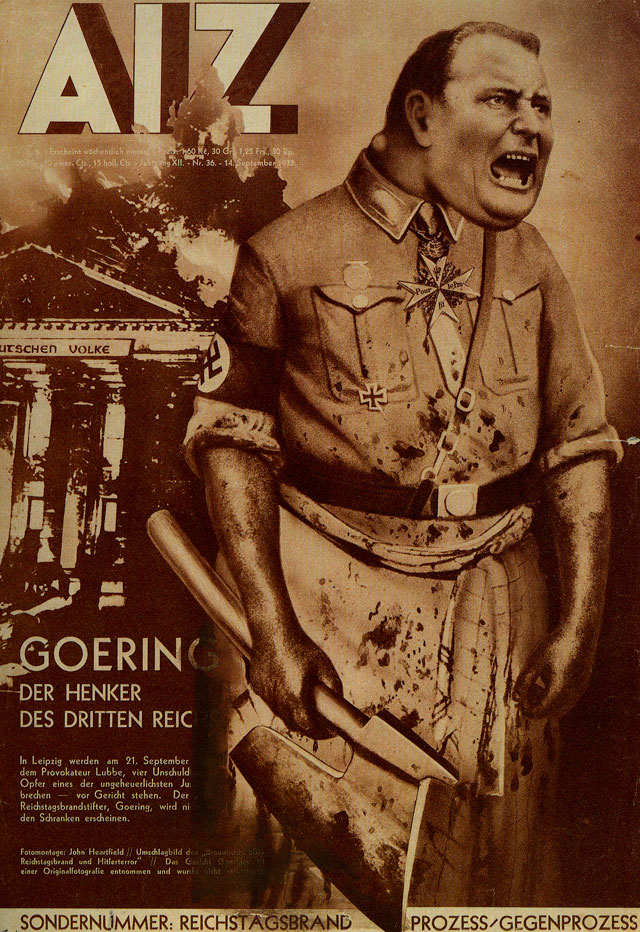

John Heartfield was arguably the most innovative collagist and practitioner of photomontage of the period, but because his output was specifically political, for many years his work remained a minor footnote in standard art histories. With a renewed interest in art and politics in the 1980s, his fantastically polemical montages were rediscovered, reevaluated, and embraced by a new generation of artists and critics. Heartfield’s fierce anti-fascist montages fueled the pages of AIZ, a daily newspaper published in Berlin and devoted to issues concerning the working classes. With savage humor and an uncanny facility in recombining images, Heartfield relentlessly attacked the inequalities and hypocrisy of German society between the two world wars. He was no longer interested in the Dada agenda of promoting disorientation for its own sake, but instead he utilized the frenetic energy unleashed by the radical juxtapositions in his photomontages to illuminate cultural contradictions and point a way toward a new political course. It is his combination of acute political insight and rigorous formal innovation that marks Heartfield as one of the twentieth century’s most under-appreciated yet influential artists.

The Americas are not without their forms of cultural collage. The foundational moment being Columbus’s encounter with the “New World,” which was a collision of imagery of epic proportion. The “Discovery” was a kind of collaging of images from deep within the European imagination onto the cultures and inhabitants of the Caribbean, eventually extending to all of the native people of the Americas. Columbus and company did not objectively recognize who and what they found in 1492, but instead projected their unsupportable fantasies that were based on medieval legend, fear, and superstition upon this entirely (to them) unknown world. From the proverbial day one, the American experience was one in which fragments of the European world were forcefully sutured upon the unwilling and varied cultures on the other side of the Atlantic.

No less important, and violent, to the making of the American hybrid identity was the importation of African slaves. For over two hundred years, millions of representatives of a myriad of African cultures were dislocated from their original contexts and forcefully implanted on American soil. The constant fear of miscegenation has fueled the uglier aspects of our culture for hundreds of years. This fear of race mixing is blind to the wondrous vitality that this displacement gifted us. Just a miniscule sampling of how these dislocations manifested themselves would have to include the following examples. In Cuba, Haiti, and elsewhere in the Caribbean, African Gods were hidden behind the faces of Catholic saints creating the hybrid/collage religions of Santeria and Voudou. Creole has given us a new lyrical language combining cadences of Africa with syllables of French with which to sing. And the musical traditions of tribal life miraculously survived and thrived on cotton plantations, laying the foundations for blues, jazz, and gospel, the musical forms on which all contemporary American popular music is based.

The third sociological phenomenon that makes America the quintessential collage culture is the massive and ongoing influx of immigrants. No other society in history has absorbed the extreme variety of identities, ethnicities, languages, traditions, styles, foods, and forms of cultural expression. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries when waves of Irish, Italian, Eastern European, Latin American, and Asian peoples were flooding the cities with fresh energies, unfamiliar languages, and suspicious cultural traditions, the “melting pot” was the dominant model of cultural assimilation. For those who embraced or longed for an essential ”American,” the idea of the melting pot was the alchemical socio-demographic answer to the dilemma of the ever-changing make-up of America’s population. The melting pot metaphor promised that the foreigners would become “like us,” that America could homogenize its extreme heterogeneity, could un-collage its fragmented identity, easing the fears of strangeness and postponing the acknowledgment of the inevitable hybridity of our culture.

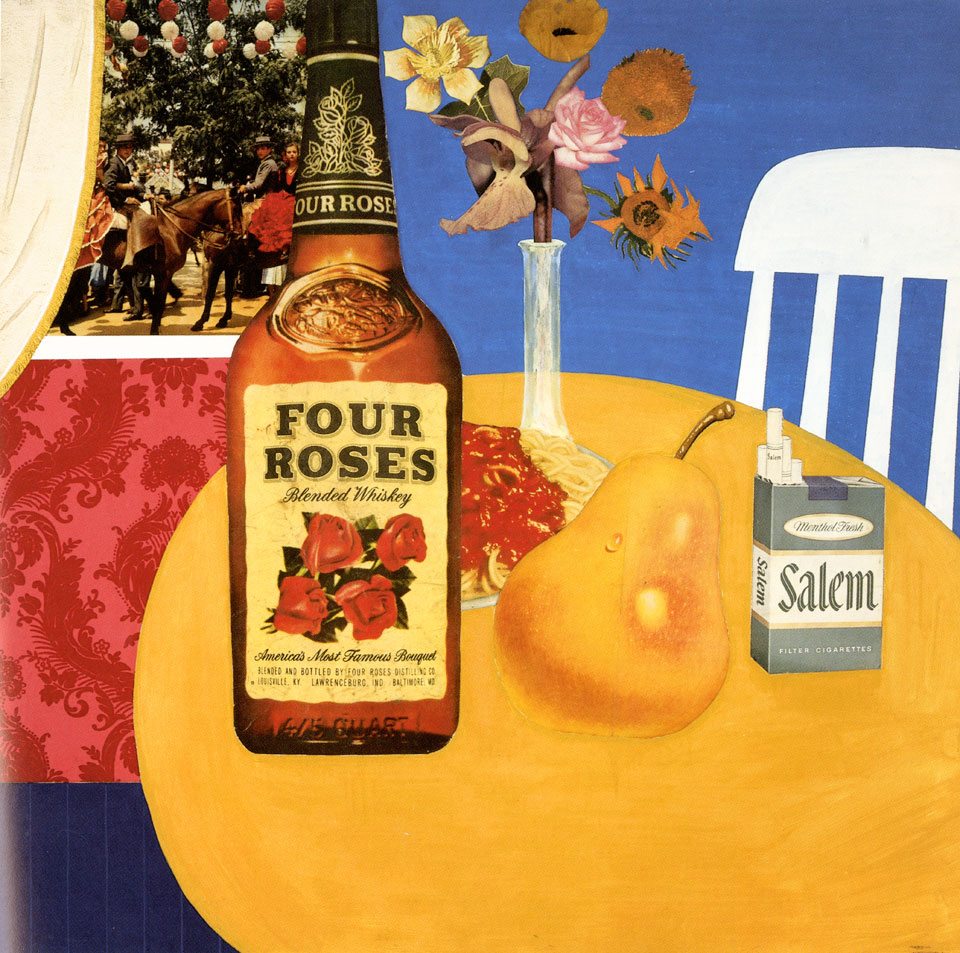

The tendrils of Dada and Surrealism snaked around the American imagination during the early-to-mid century but it wasn’t until the Pop art environment of the 1950s and 60s that collage fully bloomed in the visual arts. Movies, television, radio, and mass-market magazines helped to spread the products and personalities of popular culture, manufacturing an endless stream of images and sound for consumption. Newspapers themselves are a daily form of collage, with headlines about world events competing for space with comic strips and advertisements for lingerie. Artists such as Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Jess, Bruce Conner, Roy Lichtenstein, and Andy Warhol utilized collage to incorporate elements and references to popular culture, extending the symbolic vocabulary of modern art while Simultaneously implicitly or explicitly commenting upon the increasingly material culture in which we lived.

Bruce Conner, John Baldessari, and Robert Heinecken, three artists who lived on the West Coast, far from the critical infrastructure of the art world in New York, share an interest in media, collage, and appropriation. Conner’s visceral and disturbing assemblages are icons of the dark side of American culture. His 1960 assemblage Black Dahlia, for example, refers to a grisly murder of a Hollywood starlet. It is a lurid and anguished sculpture in which nylon stockings are stuffed with pornographic photos of a woman in bondage, peacock feathers, sequins, bits of lace, and other objects relating to a crime scene. Indicative of the sarcasm and dark humor that characterized much of Conner’s work, and suggesting that his art works were somehow dirty and illegitimate, Black Dahlia was one of a group of assemblages that he made in this period that he called “rat bastards.” Like collagists before him, Conner used the material of his own culture to make his work literally and figuratively of its time, But it is his work in film especially that has had an enormous and lasting impact. It is difficult to imagine how music videos would look today, had Conner not made short experimental films such as A Movie (1957) and Cosmic Ray (1961). Using appropriated footage, and editing and sequencing the films to suggest and deny narrative catharsis, Conner also used popular songs, such as Ray Charles’ That’s What I Say, as soundtracks for his non-sequitur-fueled collage films.

Robert Heinecken’s work has not received the critical attention it deserves. Heinecken helped to reinvigorate photography as an art form just as it was beginning to exhaust its mid-century purism as advocated by the f.64 photographers such as Edward Weston, Ansel Adams, and Imogen Cunningham. Throughout a career spanning four decades, he has treated photographs to innumerable permutations, appropriation, collage, photograms, photo-sculptures, and the like, using advertisements and pornography as his sources for pre-existing imagery. Heinecken was a kind of proto-post-modernist whose famous dictum ‘A photograph is not a picture of something, but an object about something” indicates his understanding that photographs are not objective windows to the world but are, in and of themselves, cultural artifacts.

John Baldessari was one of a group of California-based conceptual artists that were drawn to photography and language as a way of distancing themselves from the precious art object. In fact, in 1970, as a kind of declaration of independence, he famously burned all of his paintings and called the burning artwork Cremation Project. By the late 1970s, Baldessari was working almost exclusively with appropriated photographs culled from advertisements and movie stills, cropping, reshaping, and reassembling previously unrelated images into a new visual syntax. That his photographs are generic is important; he is more interested in the cultural phenomenon of how photographs surround us in every aspect of our lives, than he is in expressing some romantic idea of the artist’s inner soul. As a way of signaling that photographs, despite their resemblance to reality are, like all visual representations, abstract constructs, he often adds paint in splashes and dot patterns, interrupting the flat surface of the photograph with references to painting. In his photo-constructions, Baldessari wants us to look “between things instead of at things.” What he means by this is that photographs, despite their apparent accessibility, are contingent upon context for their meaning and must be “read” like anv other form of information.

It is a cliché to state that artists have unique vision, but of all of the varied and disparate visions represented in this exhibition, Gordon Matta-Clark was an artist of extraordinary individualism. Son of the Chilean Surrealist painter Matta, Gordon’s life was tragically abbreviated by cancer at the age of 35 in 1978, surely robbing us of years of the intelligence, risk, and violent beauty that characterized his prolific experiments in sculpture, performance, and photo-collage. Associated with New York conceptual and performance artists like Laurie Anderson and Vito Acconci as well as with earthworks artist like Dennis Oppenheim and Christo, Matta-Clark embodied the anarchic and experimental spirit of the late 1960s and early 70s. He is best known for his architectural interventions in which, with buzz saw in hand, he would carve away part of domestic and industrial buildings, revealing and creating new associations of space and light, interiority and exteriority. Conical Intersect (1975) was executed as part of the Paris Biennale in which he cut through two adjacent seventeenth century townhouses that were slated for demolition. His sculptural works often had three manifestations: the actual site-specific intervention, fragments of buildings re-contextualized in a gallery setting, and thirdly, his obsessively documented projects transformed into photo-montages or collages that were two-dimensional equivalents of his architectural projects.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, a generational shift occurred in American art. Minimalism. Color Field painting, and Conceptual art were, seemingly, on their last legs, precipitating a paradigmatic shift in the concerns of young artists. Jenny Holzer, David Salle, Richard Prince, Barbara Kruger, Cindy Sherman, Sarah Charlesworth, and David Wojnarowrcz are just a few names of the new generation of artists who came to prominence in New York at this time. Although difficult to generalize about such a varied group, one can say that all of these artists were interested in the personal and collective effects of our image-saturated culture.

Of this generation of highly influential artists, certainly Cindy Sherman occupies a category of her own. Beginning with Untitled Film Stills, a smart but relatively humble group of black and white photographs from the late 1970s, Sherman has stimulated an entire generation of artists to explore photographic portraiture, theatricality, and kitsch. Sherman herself is almost always in the picture, yet they are never pictures of her. She is not interested in self-portraiture in the traditional sense. She is interested in how the images that are culturally constructed and disseminated are internalized by those (all of us in America) who are caught in their incessant flow. Her photographic projects are released on a yearly basis, each group of images exploring yet another niche in the archive of images: soap opera girls, the centerfold, mad women, mythological creatures, B-movie monsters, and art historical figures. With elaborate costuming, prosthetic devices, sex toys, and fake body parts from joke shops, Sherman “constructs” her figures out of personal and cultural imagination. Her portraits are familiar, yet there is something obviously wrong; they do not seem wholly complete. Sherman collages her identities, using all of the right ingredients, but the parts never add up, leaving us with the creepy feeling that despite our best efforts to hide our stunted selves, the cracks in the surface will always give us away.

David Wojnarowicz died of AIDS-related illness in 1992 at the age of 38. After having run away from home as a teenager, he survived on the streets of New York as a hustler, eventually becoming involved in the East Village art scene as it exploded in the late 1970s and early 80s. Wojnarowicz was a kind of street-smart visionary folk artist, whose paintings, photographs, collages, sculptures, performances, and writings were roiling with his fury at the violence, intolerance, and hypocrisies of Reagan-era America. His voice was distinctive, with a zeal one might associate with a man on a mission. His embrace of collage allowed him to incorporate other voices and sources in his work, opening up his emotional palette to include humor, chance, and contradictory opinions. Tommy’s Illness/Mexico City (1987) is a field of symbols related to Mexican popular culture-the Virgin of Guadalupe, the pierced heart, a cactus transforming into a turtle, and a shattered facade of a building that must certainly reference the recent earthquake in Mexico City. These symbols seem to orbit around a reclining figure painted over a map of Mexico. Collaged into the mix and bleeding through the underpaint are cartoony grotesques, illustrations from a Mexican newspaper story about Hollywood monsters. It is a rich, dreamy, and provocative constellation of images. As with much of his work, the bits and pieces of printed matter that collide and collude with his own images, present a kind of visual diary of the places, people, and issues that were important in his political, artistic, sexual, and emotional life.

Of all the works by American artists in this exhibition, Barbara Kruger’s images come closest to mimicking the work of early twentieth century photomontagists like John Heartfield and Alexander Rodchenko. Although largely seen and distributed through the gallery system, Kruger has found many public sites for her work, including billboards, T-shirts, and shopping bags. Initially trained as a graphic designer, since the late 1970s Kruger has used appropriated imagery and bold graphic texts in order to provoke or interrogate societal assumptions about power. Her work deliberately looks “collaged” in its crude cutting and pasting techniques, yet there is more fragmentation occurring here than immediately meets the eye. She is a partisan in the battles for feminist issues and her precise use of words such as “you,” “me,” “your,” “my,” and “our” in pieces such as Your Gaze Hits the Side of My Face or Your Comfort is My Silence, explicitly challenge the viewer to choose and/or recognize what side they are on. Kruger’s work is polemical and not very polite. She pushes people’s buttons attempting to question long-held assumptions about what art should (or should not) address.

Although the Starn Twins and Christian Marclay are not generally associated with the first wave of New York post-modernist artists, their careers began their trajectories in the mid-1980s. The Starn Twins employed photographic materials, processes, and techniques in ways that undermined the preciousness of photographic modernism. Their photo-constructions are made from deliberately torn bits of photographic paper, reassembled with cellophane tape, stained from uneven development and toning, with squiggly dust lines interrupting the clarity of the photographic window. For the Starns, the photograph is as much an object as it is an image. Interested as they were at the time in romanticism and nostalgia, through the cultivated distress of their processes, their images attain an aura of age and garner a patina of decay.

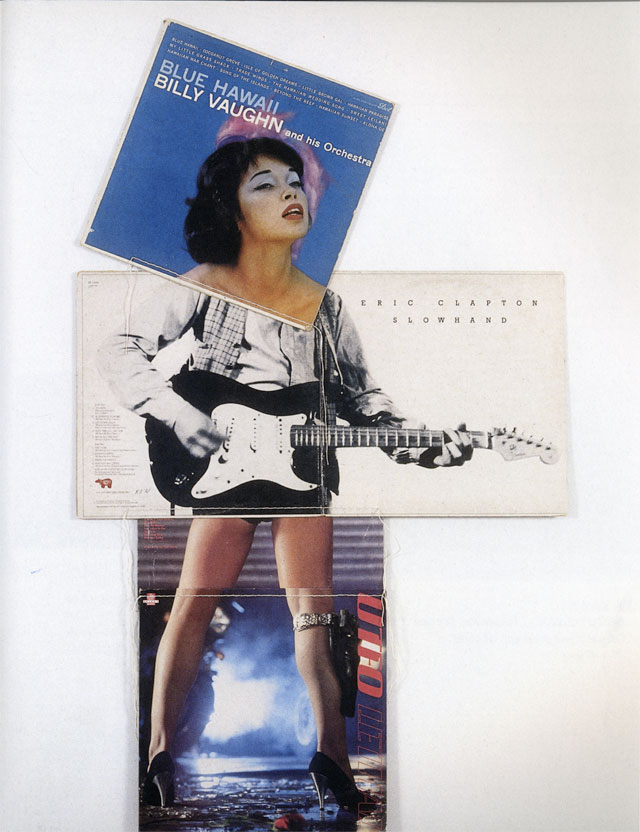

Marclay is a sound artist, performer, and sculptor whose themes and concepts revolve around music and the devices and mechanisms of its history. Over the last twenty years he has worked with found sound, audiotape, and reconstructed musical instruments, creating a unique body of work that marries musical and artistic heritages. His series of collaged album jackets began in the early 1990s when the LP was being replaced by CD technology. With reference to Dada and Surrealist artists such as Hannah Hoch and Hans Bellmer, Marclay’s “exquisite corpses” mix gender and race in humorous and perverse assemblies of the human body while acknowledging the fast-disappearing, soon-to-be-dead format of the album jacket.

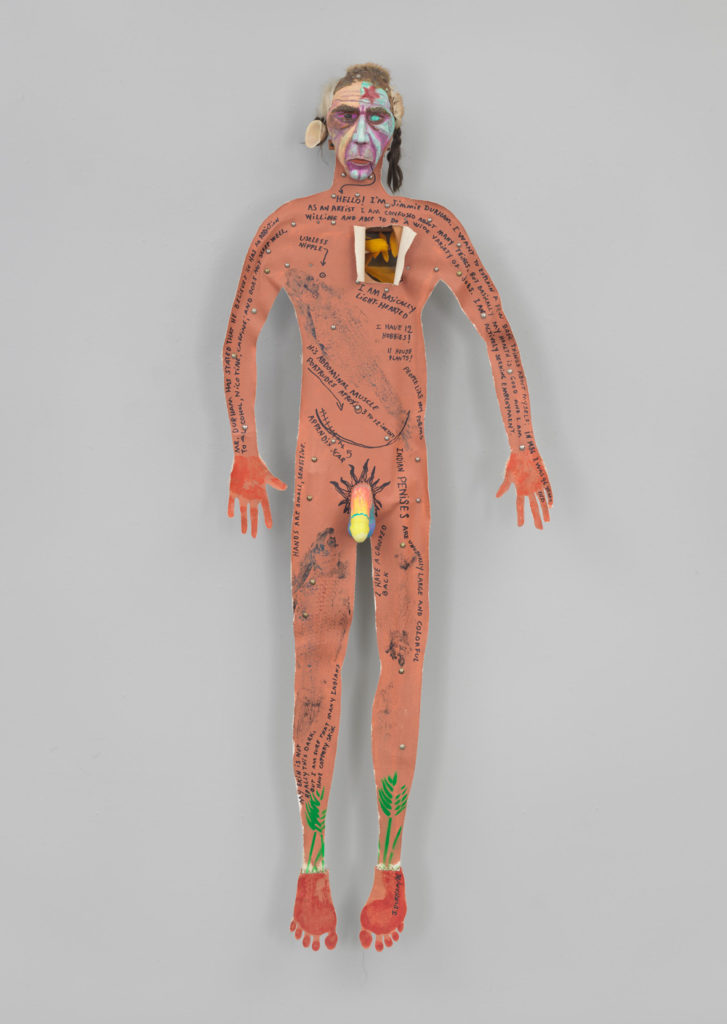

Jimmie Durham is one of the most important artists of the last twenty years. His work in sculpture, installation, performance, and writing has had broad and deep influence here in America, in Europe, and in the Third World. Born in the United States of Cherokee descent, Durham, through his work, has investigated the impossibly thorny terrain of what it means to be an “Indian.” This fundamental mis-recognition of Native Americans (another term he disputes) is the shaky foundation on which our entire American history is built and becomes the primary metaphor in all his work. With ferocious wit, Durham plays in the fields of cultural identity making what he calls “fake Indian art.” Mixing materials with “native” associations with those of “industrial,” like his PVC-pipe serpents or his ritualistic-looking car muffler, his assemblages are funny and rhetorical, tweaking the boundary between the homemade quality of arts and crafts and the rarified world of conceptual art. Self-Portrait (1987) combines canvas, wood, paint, feathers, shell, turquoise, and metal in a satiric comment on self-as-Indian-on-display. With references to hunting trophies and ethnographic documentaries, Durham’s work is both sarcastic and touching, mocking both himself and the culture that labels and “reads” him as “Indian.”

Stephen Frailey is currently working in a manner that might be considered “post-collage,” in that the disparate elements he utilizes are not in asynchronous relationships but seek, despite their material differences, to be of a whole. These pictures are indexes of some things placed in front of the camera. The lighting is good, the objects clearly described, the textures and colors within the realm of the recognizable. The pictures are declarative, like bright announcements, yet the captions have been excised; just what is being declared? As Roland Barthes has suggested, photographs are tautological: A picture of a hat looks like a hat, it appears to be both a representation and the thing itself. Frailey employs the obviousness of the photographic gesture, this pointing at something and saying “Look!” A shape floats in dark water, or an irregular frame sits upon a black velvet cushion. A second element is tucked into a cranny or fills a scooped-out oval. Perhaps we recognize one element or maybe even both-is that power-steering fluid in a cookie sheet? Is that a dry sponge on an automobile floor mat? Frailey’s juxtapositions are symbolic nonsense, they defy our desire for narrative closure, yet somehow provide pleasure in their simple arrangement.

The revolution in personal computers and digital media is the fulfillment (on formal and technological terms at least) of much of what twentieth century artists have been seeking. Speed, fragmentation, and reassembly-ideas hailed as the antidotes to the tired traditions of the nineteenth century are the characteristics that describe our natural environment. Most of us now have access to relatively low-cost, highly complex machines that allow us to be not only consumers but also producers. We make our own websites, combinations of word and image of our own devising. We employ Photoshop to digitally manipulate imagery, clearing up blemishes, cutting an unwanted person out of the frame, and inserting others into the frame. With a couple of clicks and drags of the mouse, we can suture our faces onto other people’s bodies. Our histories are no longer anchored solely in the provinces of storytelling and photographic evidence. Like the plastic surgery-enhanced bodies we can opt for, we can recreate our visual past without the violent telltale tears or cuts from an old pair of scissors. Our collaging is seamless with edges softened, airbrushed, and blended-in with the new background.

Digital technology has changed the way we think about communication, visually and textually. When we browse the World Wide Web for example, we are participating in a system of links that embody a living collage of images and texts. Words and images appear on our screens with highlighted links to other sites of words and images. The link is the doorway between physically discrete bodies of information, providing us with the opportunity to experience and assemble information in a multi-sequential manner. Hypertext as a system, method, and structure in some aspects resembles the processes of the collages of Cubism. What is fundamentally different is that hypertext exists in a virtual space. The cutting and pasting is electronic not physical and no matter how extreme the juxtaposition of word/image/sound, it remains safely within the realm of the virtual. The violence of the cut, the tear, the incision, the excision, and the reassembling of fragments is muted if not rendered utterly benign by the ease, invisibility, and non-physicality of digital process and product.

The artists of the early twentieth century saw the future as a collaged future, but they mistook the form for the content, for although their premonitions have come to pass, the power of collage to disturb and disrupt has been largely absorbed and neutralized by the ability of culture and technology to distance violence. This is not to wax nostalgic for the rabble-rousing, utopian, or anarchic conceits of collage of a century ago, when collage meant to shake viewers out of a slumber, be it political or esthetic. Today the hyperbolic proclamations of that fervor still can be heard echoing around the halls of the digital world with endless claims for connectivity and universal access to information. We now have the freedom to slither through the electronic passageways along tangential lines, following thin threads of connectivity until our eyes dull and fingers ache.

Obviously the Web and related digital technologies are not the utopian spaces we had hoped, but perhaps the problem is not with software monopolies or the usurpation of the net by commercial interests. Gratefully, at this point at least, no technology can change the actual content of our souls. Despite technological advances in which the representations of reality have become glossy, slippery, and ever changeable, our internal landscapes are every bit as murky and stubborn as at any other time in history. This murkiness is the primeval ooze from which the artist’s imagination springs.

Martina Lopez, Zoe Beloff, Diane Bertolo, and Paul Chan are the four artists in this exhibition whose work largely employs digital technologies for its concepts, processes, and presentation. Lopez updates the visual history that is the family photo album. Photography fostered a myriad of esthetic and sociological revolutions; for example, before the invention of the fixed photographic image, only relatively wealthy families could employ artists to render the likenesses of its members. Through the course of the second half of the nineteenth century, daguerreotypes, tintypes, and the carte-de-visite were the three most common forms of commercially available photography, precipitating an explosion of imagery of common folk. With references to the nineteenth century multiple image photo-collages by Oscar Rejlander, Lopez digitally cuts and pastes portraits from her own family history to create computer-generated tableaux inhabited by the photographic ghosts of her ancestors.

Zoe Beloff’s CD-ROM Beyond also takes its inspiration from nineteenth century technologies. Beloff acts as the spirit guide, our “medium” through the media of early photography, film, and sound. For citizen’s of the nineteenth century these new technologies were not always understood as advances in science but sometimes were related to the occult; the phonograph disembodied the voice, the photograph captured the soul, and cinema resurrected the dead. In Beyond, photographic landscapes are sutured together to expand to a 360 degrees environment through which the viewer can move, change direction, look up or down, zoom in or out, and click on icons to open short looped movies. Beyond is a mysterious virtual world exploring the paradoxes of technology, desire, and the paranormal in which the interactive viewer connects late ninetieth and late twentieth centuries and activates the collage process as it unfolds in a virtual space in real time.

Diane Bertolo’s work explores, symbolically and procedurally, the relationships between technology and personal and social construction. She claims to ground her work in equal parts media theory and old-fashioned quackery. Bertolo often uses the Internet as a site and activator for her work. In Channel/Untitled, for example, she uses the model and metaphor of Morse code to “communicate” with the disembodied voices of the technological age and explore the magical possibilities of the telephone, the computer, and the radio. While the viewer/participant interacts with the piece, certain signals from the Internet itself are simultaneously feeding into the system, bringing chance operations into how the piece unfolds. For this exhibition, Bertolo presents the projection piece Over/Time, ambient artwork that takes the form of a temporal and variable collage. Her image sources include classical Greek statuary, medical images such as microscopic views or cells, and nineteenth century photographs of women hysterics. Bertolo hooks the image sequence into the computer’s internal clock which then regulates the image juxtapositions, evoking issues of time and decay, the frailty of the human body, and the blurring boundaries between bodies and machines.

Paul Chan’s CD-ROM presents a kind of digital slide show featuring details from his epic animation Happiness (Finally) after 35,000 Years of Civilization, in which he reinterprets the drawings of outsider artist Henry Darger and the writings of utopian socialist Charles Fourier. Historically Darger (1892-1972) and Fourier (1772-1839) could never have met; in Happiness, Chan provides a digitally animated landscape in which the works of these two visionaries could meet, intermingle, and mutate. Within the multi-narratives of Happiness, Chan not only recombines Darger and Fourier but he also inserts fragments of other figures from both art history and twentieth century political events. In the illustration for this catalog, Chan has reconfigured one of Darger’s girl heroes in a reference to the violently reshaped dolls of the Surrealist artist Hans Bellmer. Chan shares a fervent desire for social justice with some early twentieth century predecessors. One can feel the outrage smoldering just below the deceptively simple cartoon imagery, yet he cannot, at this late date, believe in the messianic promises of politics or technology. Chan’s work is an example of how collage has been fully internalized by technology and contemporary esthetics. For Chan, all of history is a collage and therefore he does not announce his process as some break with the past; for him it is entirely natural to appropriate and suture together images, figures, and philosophies to create a fantastically apocalyptic in which the ruins of culture can be reassembled and reassessed.

I began writing this essay in Bard College’s Stephenson Library. Several mornings a week I would sit with my laptop amidst four Corinthian-style concrete columns approximately thirty feet high and embellished with a patina of polite decay. The columns support a massive concrete slab that meets the slanting glass panels that serve as the roof. The shadows from the skylight frame stretch across a large abstract painting hanging on a wall of polished brick. The painting is a pale white with occasional black bars, suggesting an incomplete floor plan. The tables are cedar with faux-marble inserts, the chairs vaguely American Colonial. A massive, centuries old, darkly stained bookcase looms over this bright interior, its leaded glass doors permanently locked, skeleton key long gone. Leather bound, gold-embossed spines read The Century Dictionary and Cyclopedia, Bentley’s Miscellany, Academie des Inscriptions, and History of the Rebellion. This study area of a liberal arts college in the first years of the twenty-first century is in itself a collage in three dimensions. It is an architecturally mixed, historical pastiche in the current user-friendly international post -modern style. A library is, by definition, a compendium, a collection, an archive of textual objects representing a broad array of human interests and obsessions. As one strolls through the stacks, it seems as if all of the adjoining spines are sutured together, suggesting a single extended accordion-like text that could unfold in a vast run-on narrative.

I finished writing this essay in my home in Baltimore, one of about two-dozen stone duplexes clustered on a hillside, built in the 1840s for the Appalachian workers of the old brick mills that line the road below. My neighbor’s satellite dish sits atop his granite-walled studio that was once a coal shed. On my walls are Mexican retablos next to framed monotypes made by a contemporary artist. A bronze statue of Ganesha is kept company on the mantle by photographs of my family and friends. An embroidered image of the Virgin of Guadalupe covers a table on which sit CDs of DJ Spooky and Erik Satie. My blood family lives in other parts of the country, I piece together an ad hoc family out of colleagues and neighbors. I use salsa verde on my french fries. Contemporary life is cultural pastiche. This is not to say that the historical contradictions, social inequities, and asymmetrical power relations that fueled the fervor of the early twentieth century have been resolved. Nor do I claim that my international shopping choices signal universal goodwill. When content is emptied of its form, collage culture does, in its way, hide as much as it reveals.

For collage to have had its impact, there had to have been a presumed “naturalness” or “seamlessness” to be broken apart. The uninterrupted picture plane, like the smooth narrative it implies, requires a central organizing force or author. God can provide this. The Renaissance window provides this. A three-minute pop song can provide this (but only for three minutes). It is arguable that one of the functions of art is to make order out of the chaos of our lives. This is art as a beautiful lie. If the twentieth century has taught us anything, it is that fragmentation, reassembly, and hybridity are the life forces of a vibrant culture; calls for purity and a return to wholeness are naIve and dangerous. Collage is our natural environment. Once it is understood that we are hybrid, culturally, psychologically, esthetically, in our foods, traditions, beliefs, and art, it becomes possible to understand relations as reciprocal. Meaning and identity are constructed in the relationship between things. The impulse toward collage is no longer one of fracture and violence but one of vitality, recognition, and temporary resolution. We can contradict and complete each other simultaneously in the misshapen group portrait that is us.