Bill Jacobson

When Bill Jacobson’s out-of-focus photographs were first exhibited in the early 1990s they were a revelation. Emotional, psychological, political, lovely and haunting, they seemed to whisper important things about the state of photography and a crisis of representation catalyzed by the AIDS crisis. Utilizing fundamental qualities of the medium, focus, framing, composition – Jacobson continues, quietly yet forcefully, to examine how photography makes meaning.

Jacobson’s photographs are in the collections of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Guggenheim Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum. He is represented by Julie Saul Gallery.

This interview took place in Jacobson’s home / studio in Greenpoint, Brooklyn on October 16, 2015.

MAD: You attended Brown University but took photography classes at RISD

BJ: In those days Brown did not have its own photography classes so RISD offered classes only for Brown students that were taught by graduate students. But because I already had some photography experience they let me enroll in the regular RISD photo classes. Ray Metzker came to teach for a semester and he really changed my attitude toward photography. He was such an extraordinary artist and teacher. I’ve never forgotten his adage, which is still relevant today, that we should be ‘making pictures as opposed to taking pictures’. He urged us to consider absolutely every choice that went into what we were doing.

MAD: I think Metzker was a significant photographic artist whose importance has been largely forgotten, especially since the photo world was absorbed into the wider art world in the 1970’s and 1980s.

BJ: I agree, and that’s also true for one of Ray’s teachers, Harry Callahan, who brought both emotional intensity and formal expertise to his images. While he is acknowledged in a general way, a lot of photo students don’t know the range of his work or how radical it was.

MAD: I just recently became aware of some of your early work from the 1970s, a series called American Trip. They are terrific and, it being young work, I can see a lot of influences such as Weegee, Arbus, Meatyard, these are among the photographers whose work were really embraced by young photographers then.

BJ: It was really Arbus who got me started taking pictures. My dad was an amateur photographer and someone gave him the Aperture monograph when it was first published. I remember it freaked him out and he put it way up on the top shelf of the bookcase. And I still remember the physical act of me scrambling up there to retrieve the book, sensing it was something I really needed to see. It was a life changing moment.

MAD: Why? What was it about those photographs that appealed to you?

BJ: It was their otherness, their transgression. Growing up in a small town in Connecticut in the 1960s I had never seen anything so upfront about homosexuality. I knew of no other visual representation of homosexuality. The New York Times still referred to homosexuals as ‘perverts’. It was seeing Arbus’s pictures in combination with hearing Lou Reed’s Walk on the Wild Side that showed me possibilities. And while I have very little aptitude for music, I had discovered an aptitude for photography. I think that photography held a promise, and I sensed it would let me connect with my sexuality in a way in a way that nothing else could.

MAD: I’ve had this conversation in various forms recently about how when we are young and feeling isolated and like outsiders or freaks, certain artists, images, songs, books or whatever, comforts us, can relieve our feelings of alienation, can suggest a way forward, can help us feel less lonely.

BJ: But Arbus was never comforting… that was the conflict. She showed me possibilities, but they were also scary as hell. Her images were a peculiar type of embrace. It was the early 1970s, so it was a very tumultuous time; the Vietnam War was still going on, we had all gotten draft numbers upon graduating high school. But the American Trip pictures you are referring to are from a few years later when I was in college.

MAD: In my early teenage years I could not wait to be old enough to be a hippie. In the late 1960s there were these hippie encampments on Boston Common and I used to take the subway in to town just to walk around and look at them, I was fascinated. By the time I was old enough to participate, the party was kind of over. I would attend concerts, anti-war rallies and mostly observe ragged looking stoned people and I would think to myself ‘This cannot be the promise of a peaceable kingdom’! In that moment I think I tapped into my innate cynicism and misanthropic tendencies. It was around that time that I discovered Arbus and it was a revelation. The ferocity of her vision frightened me too but I was mesmerized by her ability to focus on the flaw, on an individual and a cultural level.

BJ: She had the ability to look into what the culture considered the dark side, and what most preferred to avoid. When John Szarkowski first showed her work at MoMA, they had to wipe the spit off the glass at the end of the day because people were so horrified and outraged by her work.

MAD: You eventually moved to San Francisco to go to graduate school at the Art Institute. Did you move there because of the school or the city?

BJ: Both, I had gone to SFAI for a junior year away from Brown, so I was familiar with it. Ellen Brooks was an important teacher to me in my undergraduate year there, and I wanted to work with her again. Larry Sultan had just been hired, and Linda Conner was also teaching there. I liked the spirit and energy of the place, and its historical relationship to photography in the Bay Area. I was coming out in those years, so just to have time away from the East Coast and family was liberating. And the light was beautiful and the Bay Area offered a very different way of living. I remember thinking in those years that New York and California were more different than New York and London. It was much more hippie than money, more working class, and the Asian and Latino and gay cultures were so present.

MAD: Did you move back to New York right after grad school?

BJ: I stayed in San Francisco for two more years. I had to figure out how to make a living and started shooting for artists and galleries. When I moved to New York I continued those kinds of photography jobs. I worked for Blum Helman Gallery for four years and then Pace Gallery for five years. I also did work for the Whitney, Metro Pictures, Castelli, Mary Boone and others.

MAD: And during that time you were not making your own work.

BJ: I took a break from 1982 to 1989. I needed to forget what I learned in grad school. It took awhile to understand the art that was being made and shown here, which was quite different than anything I had seen before. The commercial work was pretty consuming. Interestingly, it also helped demystify the gallery scene as I met a lot of dealers and artists through working for them.

MAD: In the late 1980s you started to make the out-of-focus pictures. I am curious about the origin of that decision. Was it initially a mistake that you saw some possibilities in or was it deliberate from the start?

BJ: It came out of a number of things. During the seven years I wasn’t making my own work, one of the things I spent a lot of time doing was going to flea markets. I ended up collecting hundreds of old photographs, and at times felt like I was in a trance going through bins, piles, old tintypes, daguerreotypes, snapshots, etc. There were so many with a diffused, out-of-focus feel. I was mesmerized by their beauty, their suggestion of mortality, and by the fact that these people staring into the camera were no longer alive but they felt alive. I found it extraordinary that photography can simultaneously suggest birth, life and death. It was also the early years of the AIDS crisis, and those old photographs were connecting a lot the emotions I was feeling about the epidemic. Another thing that happened was that I did some travelling with a medium format range-finder camera, which was difficult to focus at times, and I came back with some accidentally blurry pictures of Mexican pyramids that I thought were pretty fabulous. The third factor was that most of the work I was doing for galleries was large-format, both 4×5 and 8×10. I spent a lot of time under the black cloth and the act of looking through the ground glass and cranking the bellows from out-of-focus to in-focus had its own magic.

MAD: Was the exact point of blurriness just as precise as the exact point of focus?

BJ: Eugenia Parry wrote an essay for one of my books and used the term ‘defocus’, which I think is technically the right word. But to answer your question, it is less precise. With a view camera, once you are out of focus to a certain extent it doesn’t change that much. The images were made in a number of different ways, sometimes through diffusion or sometimes with lenses that I would make myself. Occasionally I would just shift the focus on the enlarger… you can really crank it and it doesn’t change that much once you have left the sharp focal point.

MAD: Do you think the AIDS crisis caused a crisis in representation especially in regards to portraiture?

BJ: It surely brought a lot of attention to portraiture. The response to the Interim Portraits was quite positive in the midst of the epidemic. And as far as I know, there was none of the negative reaction that Nicholas Nixon received at the time. Simon Watney reviewed a show I had in London and he talked about them as representative of how so many felt in that extreme time of loss and absence. There was a relationship between the pictures I was making and a sense that most of a generation was fading away during those years. The images raised the question of how we try to hold on to memory, and the accompanying futility and frustration. However, I didn’t intend for them to speak specifically about the epidemic, but rather how I was feeling during that time. Some reviewers described them as portraits of people with AIDS, which totally pissed me off, as I neither stated nor implied this. Also, many in those years didn’t know their HIV status.

MAD: Did it matter who you were photographing? Portraiture is about specificity but because your subjects are defocussed, individuality is somewhat lost.

BJ: There is a funny answer to that. Because the images are so intentionally light and bleached out, if someone had very dark or long hair I couldn’t work with them, as it was hard to keep hair from going dark. I was printing them on color paper because I could get a softer tonal range, though the one place I couldn’t achieve this was in the hair. There is nobody with a beard in the pictures, so the selection had a lot to do with a physical lightness. But ultimately my choice of models had to do with sensing a vulnerability in someone and that a kind of intimacy might come from within towards the camera.

MAD: They are all gay men.

BJ: Mostly, but not exclusively. There are a few women who I worked with as well. Now that 25 years have passed, issues of individual mortality, implicit in every portrait, have become clearer. As far as I know, only two of the men I photographed in those years died of AIDS. One of the men who posed for me, a photographer named Fernando Bengoechea, was lost in the tsunami in Sri Lanka, and two others died of other illnesses.

MAD: A few years ago I saw one of your Interim Couples images in the Hide/Seek exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in D.C. The exhibition stirred controversy that echoed the culture wars of the 1980s and early 90s, particularly around a video by David Wojnarowicz, Fire in My Belly that was ultimately censored when the curators caved to the complaints and threats of conservative politicians. What was your experience of that whole series of events?

BJ: It didn’t surprise me. The Christian Right seems to have certain artists and topics they like to pick on whenever they can. Giuliani never look sillier than when he went after Chris Ofili and the Brooklyn Museum.

MAD: The titles of your projects suggest that language is very important to you. Songs of Sentient Beings for example, is a lovely phrase that, to me at least, recalls Walt Whitman’s Song of Myself.

BJ: A lot of the work from the 1990s had the word ‘interim’ in the title. There are the Interim Landscapes, Interim Portraits, Interim Figures and Interim Couples. The word suggests something or someone that is here temporarily, for a brief moment in time. The implication is that any person, any situation, in the greater scheme of things, is here briefly. We are all interim office holders on some level.

MAD: I like the word and realize that I don’t use it very often, perhaps I will now. Interim is different from moment or instant, which are always used to describe photographs, as in the frozen moment. An instant or moment suggests a fraction, an almost immeasurable amount of time. But interim, although temporary, could be relatively long in comparison. It suggests not an instant but a span, or space or time that is undetermined. It gives us some breathing room.

BJ: I used to go to the Zen Center when I lived in San Francisco and they used the phrase ‘sentient beings’. It means a person with great awareness or feeling, so that is where that title comes from, as well as the reference to Whitman. With each series I use a main title, and then for each image add on the negative number to title the individual photograph. It bugs me when photographers apply a title to every image. Sometimes it works, but mostly it feels way too heavy handed.

MAD: In the late 1990s and early 2000s you began not only to work in color but also outside the studio. These pictures are defocused as well and although they are on the street, they are different in almost every way from classic street photography; they are almost the opposite of the ‘decisive moment’. If there is no decisive moment, when the formal and narrative elements of a photograph cohere within the frame, when is the moment for you that you release the shutter? How do you make that decision?

BJ: That work was highly influenced by a trip to India in 1999. I came back obsessed with color in a way I hadn’t before, as well as how extraordinary people look moving through public space. After returning to New York, I started bringing my 4×5 view camera on a tripod into the streets, making pictures based on the architecture, the light, and the movement of bodies. I would stand in each location for an hour or so, recording the light change and who I saw coming down the street and through the frame. Even without a camera, one of my favorite things is to just stand on the corner and watch the city go by…it is always the most extraordinary parade! It seems I have always been a voyeur, and find the very act of looking pleasurable. I remember being 5 or 6 years old and just looking out the window of the house or in the car, mesmerized by whatever was happening.

MAD: The next body of work is titled A Series of Human Decisions (2005-2009) and these pictures are sharply focused, and all about the specificity of the objects within the frame. Had you gone as far as you could with the out-of -focus imagery?

BJ: It became clear that after 15 years I had done what I could with the out-of-focus images. Then the shift in the work coalesced through my move from Manhattan to Greenpoint. After living twenty years in one place, the three month process of packing was intense…it meant that I had to hold and examine every object in my life, and this led directly to A Series of Human Decisions . They’re not just about what we collect. More directly, they’re about a whole range of decision-making that starts with the need or desire to make an object, through the it’s distribution and acquisition, to the possible discarding and reacquisition of that object through flea markets or any other channel. Then someone chooses to make a picture of that object, and perhaps that picture is then displayed in a certain context and size, in a particular colored frame on a certain wall. So the title refers to the whole range of decisions that suggest multiple levels of making and using, and the range of the physically built world. The photographs are shot in high-end museums and thrift stores, psychiatrist’s offices and artist’s studios, as well as many other locations. They are about an acceptance of the visual and emotional complexity of the world around us. Through creating equivalence, there’s absolutely no sense of irony.

The out-of-focus pictures reflected traces of people going through the world, suggesting the fine line between presence and absence. Similarly, these sharp pictures of objects are also traces of people’s lives, implying that they will also not exist for eternity. I never take objects for granted. When I look at a brick wall, I think about the person who laid the bricks, and how the laying of them is implied. There is always a trace element of the maker. It is such an overlooked thing because we are surrounded by so much. Great monuments are recognized, but someone put in the electricity, somebody made the carpets and toilets. The whole range of human production never ceases to fascinate me. It’s indeed like a giant flea market.

MAD: Your project Some Planes (2007-2008) are landscape photographs, although the image is vertical rather than the expected horizontal orientation for a landscape. This does a couple of things – it moves the images toward abstraction in the sense that two fields are juxtaposed, that of sky and ground. It is a photographic collision, a perceptual collision it happens that way because of the way you orient the camera and crop out details that may have been distracting.

BJ: I was swimming one time and thinking about how each time I turned my head to breathe, the water became a horizon line. It made me wonder if I could find locations in nature that had the same straight line that I was finding in the man-made world. Surprisingly that took some doing (laughter), as most vistas are interrupted by buildings, mountains, boulders or cactus. The cornfields of the Midwest had way too much foreground detail to work. But with lots of research on the Internet I found three different desert locations that seemed right: Great Salt Lake, the Painted Desert and White Sands. And while most would consider these to be landscapes, for me the land and sky with a straight horizon became a series of equal rectangles and the extraordinary light that surrounds them.

These collisions, to borrow your term, exist in the real world. The line of the horizon is not that different than what happens right in front of us between the edge of this computer or the edge of the table that it sits on. If you were to frame this through a lens, it would be an identical collision. Most of my work from the past decade suggests framing, but the pictures are also about the constancy of an edge as an essential part of how we perceive the world around us. It is not just the camera that frames; we are always looking at the world through rectangles, through windows, doorways, our computer screens, our televisions. I came to recognize the rectangle as the ultimate archetype of the built world.

MAD: Why was it important to go to all that trouble to find those places and photograph there? You could have done that in the studio.

BJ: It was partly the same reason I began the Interim Landscape series almost 20 years before. I go through periods when I need to leave the city, and that all the urban work I had been doing left me feeling constrained and claustrophobic. I really needed some open space and, it was an extraordinary pleasure to witness a far-off horizon line. As much as I love the city, at times it can feel like a brick wall that takes over my vision. Though of course I did make a few mock-landscapes in the studio using black and white boards, and it’s impossible to tell them from those made in the desert.

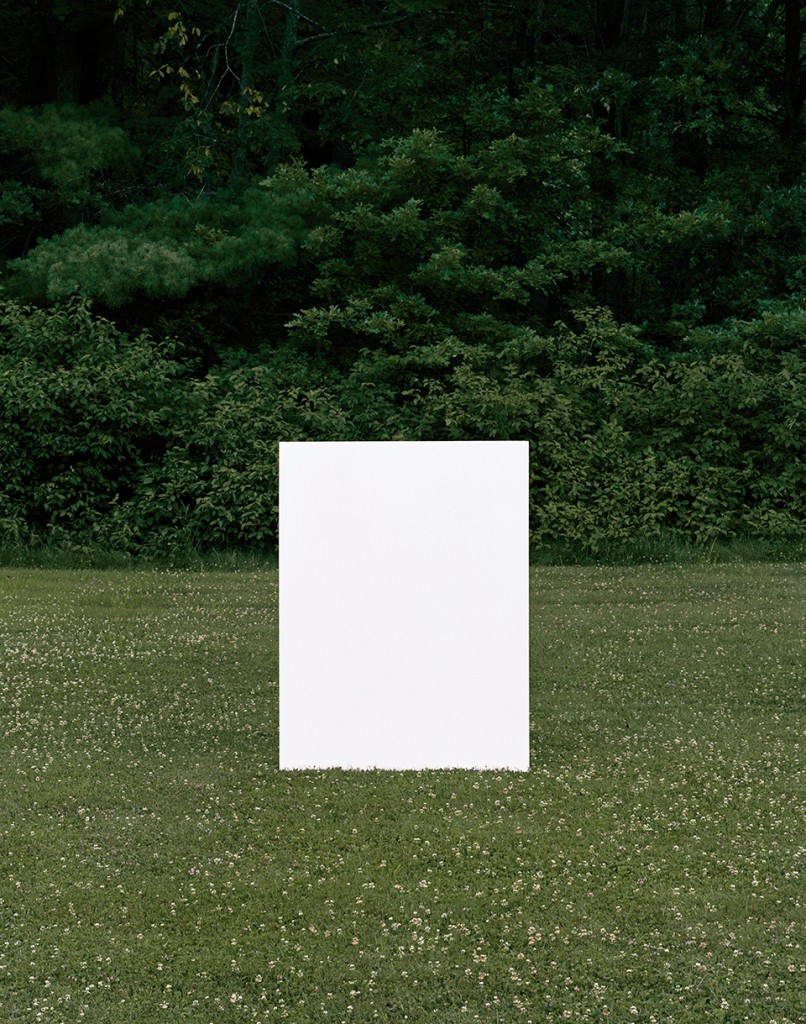

MAD: Let’s talk about your recent Place Series (2009-2013), which are also about rectangles but are very different kinds of images in which you place rectangles of color or miniature photographs in a landscape or leaning against a wall in room.

BJ: They continue my concern with how we perceive the horizon line, or the edge, but the Place (Series) extends the idea to the act of framing. I leaned either solid colored boards or photographs that I made against walls of different shades of grey, or black, or white. Some are shot outside, propped up in a landscape, or held aloft by my assistant in an urban environment. With Place (Series) #658, everyone thinks I’ve re-photographed a Mondrian, although Mondrian never used these colors. It is a detail of a 40-foot high mural in Culver City that I photographed and shrunk down into an 11×14 inch photograph, then leaned it against that wall and used as a prop.

MAD: To relocate the image or the rectangle in an unexpected place may seem like a relatively simple gesture, but it raises all sorts of questions for me about perception, what is ‘natural’ in an image, how photography naturalizes its subject, about display. They also speak to idea of pictures as constructions and of the Renaissance window in the history of art.

BJ: Thanks, Mark…you just perfectly summed up what this work is about. (laughs) They also reflect my engagement with artists such as Malevich, Morandi, Ryman, and Serra. The blank white rectangle, which pops up constantly in the real world once you start to look for it, has always held special meaning for me. On a poetic level, it suggests the start of all images up to this date, and the starting point for those that have yet to be completed.