William Lamson

William Lamson is a photographer turned interdisciplinary artist. His diverse projects explore the relationships between wonder and science, transformation and futility, endurance and the poetic. His work is funny and smart, ambitious and accessible. He is also prolific, in this conversation we did not get around to discussing many amazing projects at length or at all including his 2010 A Line Describing the Sun. In this immersive two-channel video installation, Lamson follows the path of the sun across a dry lake bed in the Mojave Desert with a Fresnel lens, melting the earth into black glass. Over the course of a day, a 366-foot hemispherical arc is imprinted into the lake bed floor. Another project we did not discuss is Solarium, a glass house made from caramelized sugar that was installed at Storm King Art Center. I encourage you to visit his website to view his works and check out the hilarious group of images / videos in ‘Actions’ involving balloons.

Lamson has exhibited his work all over including the Brooklyn Museum, the deCordova Museum, the Moscow Biennial, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Denver, University Art Museum / Albany, Kunsthalle Erfurt, Germany, Honor Fraser in Los Angeles and Pierogi in New York. In 2014, he was the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship.

This Conversation took place at the International Center for Photography in New York on February 28, 2015.

MAD: I am interested in the issue of performance versus documentation, how they are very different things. If we think about some of the most iconic performances of the 1960s or 70s, whether it is Chris Burden, Ana Mendeita, Joseph Beuys, or Carolee Schneeman, for example, the photograph became a rarified document of an ephemeral or transitory event. I’m sure that for some of those pieces several if not many frames were taken of the event but one or two of them have become the iconic representations. But with current technology we can photograph or record everything with decent sound from any and all angles. This has changed the ‘look’ of performance and maybe how people conceive and execute transitory actions. Can you address the relationship between performance and documentation in your work?

WL: Since my work often involves performing in front of the camera, both the performative action and the documentation have been really important to me. However, I think my photographic background has made me far more comfortable with the idea that my work is performative, but it is not a performance per-se. This becomes very evident when you look carefully at the videos I have made. The documentation is very constructed in terms of where I place the camera, how it moves with the action, and how it is edited together in to a one or multi channel piece. Those decisions shape the experience of the action and ultimately create the work.

For example, if you look at the film documentation of Chris Burden’s Shoot, its only 8 seconds long its anti-climactic. I think the photograph of him standing before the man with the rifle is a far better representation of the work because it isolates that moment of tension and anticipation

In my case I am not doing a single ephemeral performance, rather the very nature the actions that I perform are durational and repetitive. This reality can be both an asset and a liability, in that an unconsidered document of this action is so boring that it is unwatchable. However, because it is repetitive, it allows me think through the many different perspectives of how to shoot this action and thus create a video that can represent the various elements that are all happening simultaneously. In the end, the video may be a construction of days of shooting, but appear as if it represents the action unfolding over of a single day. By comparison to the artists using photography and video in the 1970s, this is a very different way of working.

MAD: Beuys, Mendieta and Chris Burden were very aware that the photograph would become the primary vehicle to convey the idea of the piece. For Shoot, Burden actually said, ‘I’m going to get shot at 7:45, I hope to have some good photographs’. Beuys would often pre-visualize the performance in terms of how it would translate into photographs; he often desaturated the scene so that it would better translate into a black and white photograph. Obviously what you are doing is different, conceptually and what the resulting visual experience is for the viewer, you are making visually immersive works, not singular iconic images.

One of the things that people seldom talk about or consider with such works is the experience of the artist in the making of performances, especially ones of great duration or that are physically challenging. The artist may pre-visualize a work, in your case, imagining what the video might look like in a gallery or museum, but what kind of experience is it for you in the first place. What is it like to water the desert, to float on that river, what does the failure to float feel like? In your Delaware River piece, I think the video communicates some of the struggle and a feeling of serenity when you actually achieve the balance in order to stand while floating down the river.

WL: There are not many instances when I forget about the presence of the camera, However, in Action for Delaware River, when I first got on the apparatus, my crew was not ready to shoot, so I was just floating with the current, experiencing this feeling of moving with the river without worrying about it would look like on camera. This experience was really important because it’s the feeling that I wanted viewers to imagine when they watched the piece. Once my crew was ready and we began shooting, I reverted back to the roll of documentarian, constantly looking and thinking about how this action can represents this experience

MAD: There is an element of futility in many of your works, different kinds of futility. In the Atacama Desert piece it turns out to be futile to try to bring the desert to life with your own hydrating mechanism – it is a metaphysical futility. With the Delaware River piece, the futility is more immediately slapstick, in which your body struggles to remain floating above the water.

WL: The physical reality of the floating device that I stand on was daunting. It weighs something like 350 pounds and it would get hung up on rocks below the surface, and I would then have to try and move it by myself. I remember the fear I felt when I was trying unsuccessfully to move this apparatus as the current was pushing me up against it. It was actually pretty dangerous. Normally I keep shooting things until I get all the perspective I might need for the video, but I couldn’t do that for this piece. There is a slapstick element, it is funny, but it was actually very difficult.

MAD: In your photographs that you were making when we first met maybe 12 years ago, there is an aspect of encounter. Usually an encounter between you and strangers you would meet in your travels. The history of photography is filled with such encounters that visualize this fundamental experience of two strangers meeting and acknowledging each other on some level, and what is implied or suggested by that exchange. Not to distill your work into one idea but the idea of encounter continues through your recent work. The encounter is not between two human strangers, but between you and larger forces and overwhelming landscapes, a scale beyond the human. Even the radio tower piece is an encounter between you and a structure that is monumental and through it you encounter and activate ethereal sounds of invisible forces.

I am wondering if your frustration with photography was that you wanted to interact with things beyond human scale.

WL: I am not sure that when I was driving around America and making those pictures I was thinking or feeling that frustration. I remember moments of approaching strangers and asking them if I could photograph them and they say yes and then they just look at you. It has been ten or twelve years since I made photographs like that but I remember so vividly those moments when language stops and it creates this very direct experience between two strangers. I think that kind of directness is what I have been looking for in all these projects.

I often feel somewhat alienated from a lot of the discourse around contemporary art that tends to focus on itself, on materials and the relationship to other artists and artworks, work made in a white room for another white room. The artists I am most interested in and the art that I make is about a physical engagement with the world and intend it for an audience that is bigger than students, critics, curators and collectors. For me the point of making art is to respond to a finite set of conditions that is inherent to our mortality and the forces that animate the universe. It is hard to imagine articulating that in graduate school. I think its hard to speak critically about these larger forces because they inherently push toward something that acknowledges the finite nature of our existence and that moves down the philosophical road toward spiritual speculations, or abstract metaphysical thinking which is not necessarily where a lot of art dialog is happening. (Laughter)

So I don’t think I was trying to get to something beyond the human that moved me away from photography but more about the fact that I wanted to do things as opposed to looking for something to photograph. So in grad school I decided to do things in front of the camera, and this was really exciting to realize that I can make stuff happen.

MAD: I want to ask you about your personal experience in the making of the works. When I was doing actions on the streets with my performance duo men of the world, we dressed in what we called ‘white collar drag’, and performed in business districts in the downtown areas of various cities. I remember so many times, just before the performance thinking to myself, ‘I don’t want to do this, it’s embarrassing, or it will be uncomfortable, it’s undignified’ etc. But once we started the performance, it was like entering a bubble in which experience was heightened. I can describe in detail what it is like to hold another man for long periods on various American street corners while traffic and pedestrians passed by. I could draw the pattern of cracks in sidewalks in Cleveland because I spent long days performing among them. Those kinds of experiences are in some ways lost to art history because we seldom talk about them, it is always the image, the document, and the experience of the viewer that dominates the discussion.

I was thinking about the silence between you and your subjects when you were actively photographing that way. That silence is an abyss, it is a challenge, and it can also be a profoundly suspended state of heightened awareness. I think some of that is happening in your work now, except you are working with the earth and with natural phenomenon and not other humans.

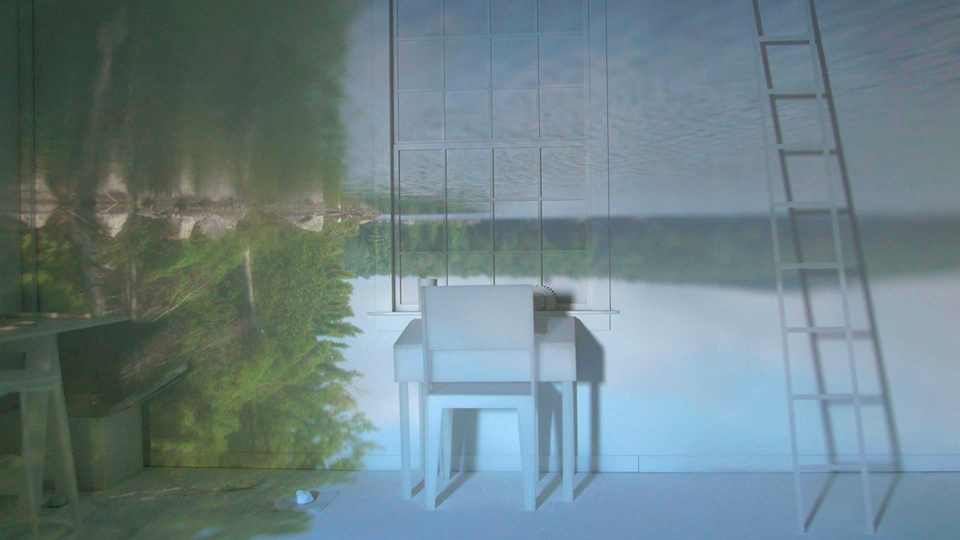

WL: The most recent experience that I have had which was exhilarating, physically difficult and at times fraught with doubt was the production of Untitled (Walden). The project involved working within a black 8×8 ft. floating camera obscura, which became incredibly hot as enclosed space. Yet what I was doing in there, framing a video camera to record the projected landscape as it moves across a model of Thoreau’s cabin, was so totally engrossing I would forget about the heat and my physical discomfort. I could have been in there for a month. Everyday was slightly different, the sun, the wind, the way the cabin moved across the surface of the water. It was like when you are first doing darkroom photography, mesmerized by watching the image come up in the developer. Except for me, this was all happening in real time, as the image world came streaming in, luminous and upside down.

That is what it was like being in this floating camera obscura watching images cohere and change in the space I was occupying. I just wanted to see what would unfold.

MAD: The camera obscura is generally understood to be a pre-photographic device – an optical tool that led to the development of photography. While that is true, the camera obscura was also used purely as a meditative device, without the goal of recording what one was seeing but simply to experience the world as an image projected into a darkened space. Before we had these recording technologies there were many pre-photographic and pre-cinematic devices that attempted to satisfy our optical obsessions.

WL: The familiarity we have with imaging technologies sometimes makes it hard to imagine it or use it in a way that is novel or refreshing. This is a challenge to many contemporary artists, using these wondrous tools that serve but no longer energize. Sometimes mastery with a tool or craft can inspire wonder, I think of Matisse and his use of scissors, what incredible things he could do with a simple tool.

MAD: I had a similar revelation with Degas when I was in graduate school or soon thereafter. I had been, of course, dismissive of past masters; in my arrogance I was blind to the discipline of mastery, that there could be something very humble about it. It was a show of Degas’ late drawings at the Art Institute of Chicago. Here he was, in his 80s already a celebrated artist, still drawing dancers, charcoal on newsprint. The drawings were filled with erasures, you could see where he rubbed out a line he thought was not quite right. I was struck by the simple yet ongoing challenge and the pleasure that he gave himself every day to find the right line to describe the curvature of a dancer’s back. That humbled me.

WL: That’s what I was alluding to when I was talking about what it was like after a project has engaged you for a while and then you are stumped as to what to do next. You start with a few simple ideas and they suck by comparison to the success and achievement of the previous work. But you have to go through this process, to remember that ideas need to be shaped as much as the materials do. I always forget the pain of starting over on a new idea.

MAD: I think your career is fascinating for many reasons, one of which is that you had reached a level of craft in photography, a level that many would have been quite satisfied with. But apparently it wasn’t enough for you and you began on a different path and had to face a lot of failure to remake yourself as an artist. I really respect that, yet there continue to be connections between your former photographer self and your current performative, sculptural self. For example, you work with things like glass, salt, sunlight, lenses, water; these are the alchemical materials of the various inventions of photography in the 19th century. As Geoff Batchen has taught us, it wasn’t simply an issue of Daguerre patenting a method for fixing the image and then ‘Ta Da! Photography was born’, many people for many years had been experimenting with a variety of materials and process. The inventions of photography are rich with brilliant discoveries and even beautiful dead ends.

WL: It is interesting that you remind me of the origins of photography because that was what I was thinking about and talking about in grad school. These ideas that informed my thesis project, were really transformative for me. The project was called Sublunar and it involved several characters who were obsessed with flight and photographing their activities in a low-tech way. One of the images is a life-size dummy being launched into the air at night. It’s a spectacle with lights on the action. I was looking at the Wright Brothers’ photographs of their attempts at flight and I realized how early photography and early science were both amateur endeavors. So the idea of the amateur is something that runs through all of my work. I was also influenced by an Edward Said lecture that warns about the dangers of becoming a specialist because it limits your ability to do whatever you want. So the idea of tinkering in art and science, which is a very 19th century idea, is something I feel very close to.

MAD: I agree that one of the freedoms of being an artist is the intellectual amateurism, which sounds terrible when you say it out loud, but amateur in the original Latin sense of the word as a lover of something, rather than a professional. This allows us to follow our intuitions and passions, through which we may become temporary experts in obscure or esoteric subjects, materials, and / or processes.

WL: I just saw the Diana Thater show at Zwirner and I read an interview with her later that day in which she talked about how she dips into philosophy as she needs it and claimed that she was an artist not a theorist and I found that so refreshing. A lot of artists talk as if they are theorists but most are not.

MAD: I think that comes from an intellectual insecurity, which stems from the academization of art. Often artists in graduate programs are expected to be fully informed on various philosophies and theories and to be able to connect to those theories to justify their work. It would be a terrible thing in this environment to be thought of as an autodidact or dilettante or naïve, but maybe a little of that would be welcome.

WL: Lately I have been really inspired by James Lee Byars who invested every object, gesture and word with a kind of mystery. He even went so far to dress as a wizard. (Laughter) I admire Beuys and Byars because what their work evokes a feeling that is akin to the mystery one feels in the natural environment. There is a difference between mystery and mystification, which is a difference that many contemporary artists do not seem to understand.

MAD: I want to ask you about futility, which is another thread in your work. You did a series of performance / actions in 2007 and 2008, mostly in the studio involving balloons. They are so simple, surprising, slapstick and philosophically brilliant. In Vital Capacity we see your head inside some kind of tall white box, you are wearing an clear mask from which hundreds of pins are protruding and then black balloons begin to fall in patterns of one, two and sometimes three at a time, while you try to use your breath to keep them away from being punctured and blowing up in your face. It’s very funny at first but it also represents a kind of hell in which the same banal affront happens to you eternally despite one’s best efforts to keep disaster at bay. As funny as it is, I find it frighteningly claustrophobic.

WL: It is funny at first, and then it goes on for eight minutes. The balloons have varying amounts of helium in them so they drop and can be held aloft differently. With my breath I delay the inevitable and in that moment there is a tension from wondering how long can this reprieve last and then another one drops and it blows up in my face. If you dip your toe into a little bit of Buddhist philosophy you realize that we do create our own hells, it’s our own delusions that upset us.

MAD: Back to futility. (Laughter) There are various manifestations of futility especially in 20th century philosophy, art, theater, and slapstick comedy. Futility is the obverse to romanticism in which the sublime is replaced by the ridiculous.

William Lamson, A Line Describing The Sun (Installation view at Pierogi’s Boiler Room space Brooklyn), 2010

WL: Well if it’s an ocean it’s the sublime, if it’s the desert it’s the futile. I’m not sure where the relationship between poetry and futility comes from exactly, but among the artists that I admire Francis Alys kind of sums it up in his piece in which he pushes a block of ice through the streets of Mexico City and documents its erasure, its melting. His work can talk about futility in an elegant and compressed way. There are aspects of my work that were not intended to be futile but became so, like trying to make the desert bloom. The visible manifestations of what we did were so miniscule compared to the effort we put into it that it was kind of pitiful. There are times in which futility is not the goal. In the Atacama Desert project the goal was not to make a futile action, it was make to make the desert bloom into a line of flowers. There are lots of artists who do things that are futile. But if the futility is without the potential for some kind of pleasure or poetics, then I am not interested.

MAD: In the Action for the Delaware piece there seems to be both, futility and lyricism. Did you expect that?

WL: I didn’t expect that. We shot it over two days and the water level dropped a couple of inches, so areas that I had floated over the first day became obstructed and impassable the second day. But showing that process helped the piece in general because it took it out of the illusionistic space of seeing me float standing on water, which I liked but I think it was a bit too easy, well it wasn’t easy at all but it wasn’t as interesting as watching someone try to get back on the apparatus after falling into the water.

MAD: It made me think about the fact that moments of transcendence are often preceded by arduous or painful periods of struggle.

WL: And unfortunately they are often followed by long horrible periods of struggle. (Laughter) If I can stage an action that had the potential for something poetic to happen, and fail, this is futility. However if something unexpected happens, and it almost always does, then this action is no longer entirely futile and I will have learned something along the way.

William Lamson, Solarium, site specific installation for Storm King. Steel, glass, sugar, citrus trees, 2012