Tim Hetherington

Earthquake 7.0 and today it is pictures from Haiti that appear on the screens and in the newspapers. A woman buried up to her chest in concrete rubble occupies the center of the frame, patches of sweat and blood wick through the gray layer of dust that coats her body. Amidst the visual confusion there are two maybe three figures next to her: fellow victims, final companions or maybe rescuers, yet she stares at the camera, as if we might save her. Every day we are confronted with variations on this theme – someone with a camera is recording and transmitting images from cataclysms, disasters and atrocities. Accompanied by vague feelings of inadequacy we routinely allow pictures of tragedy and violence to filter through our consciousness like an unpleasant tasting beverage. What is the responsibility of the viewer? To send a check, sign a petition, shake our heads secretly grateful we were spared? And what is the role of the photographer; is it simply to witness tragic events dispassionately and record them for some abstract idea of an informed citizenry?

Although the ethical issues of documentary and spectatorship can never be satisfactorily resolved, photographers from Lewis Hine to Susan Meiselas have wrestled with these questions and struggled to redefine themselves as more than just passive observers. In order to elevate the activity of witnessing above parasitic voyeurism, photographers need to believe that their images can make a difference. Yet that very faith can destabilize a photographer’s determination when nothing seems to change. With his unblinkingly grim and unsentimental imagery of famine in Biafra, war in Vietnam and civil strife in Northern Ireland, the great British photojournalist Don McCullin sought to disturb the comfortable middle class while it sat around the dining room table drinking tea and gobbling scones reading the Sunday paper. Despite his fierce efforts, McCullin’s campaign against apathy was undermined by the public’s indifference: he began to doubt the efficacy of his imagery and was troubled by the mercenary aspect of being a war photographer. He has since retreated from the contemporary world of violence and mayhem to quietly photograph historical landscapes.

As if the torch had been passed to someone younger and less damaged by what he has seen, Tim Hetherington seeks to counteract public torpor and lobby against apathy with his powerful imagery. And although he claims not to care for photography per se, he has become one of the most accomplished and interesting photojournalists working today with ongoing assignments with Vanity Fair, ABC and CNN. Hetherington loves language and story telling. He studied literature at Oxford University writing his thesis on Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake. But after extensive travels in India, Pakistan and China, he found that words ineffective in communicating what he had seen and experienced. Then a friend took him to a screening of Chris Marker’s San Soleil and it was an epiphany. Marker creates highly discursive essay films that explore the meaning of images in relationship to personal experience and collective history. Hetherington was enthralled and understood that he wanted to be an image-maker. His first step was to study photojournalism in Cardiff with the goal of shooting for the local press.

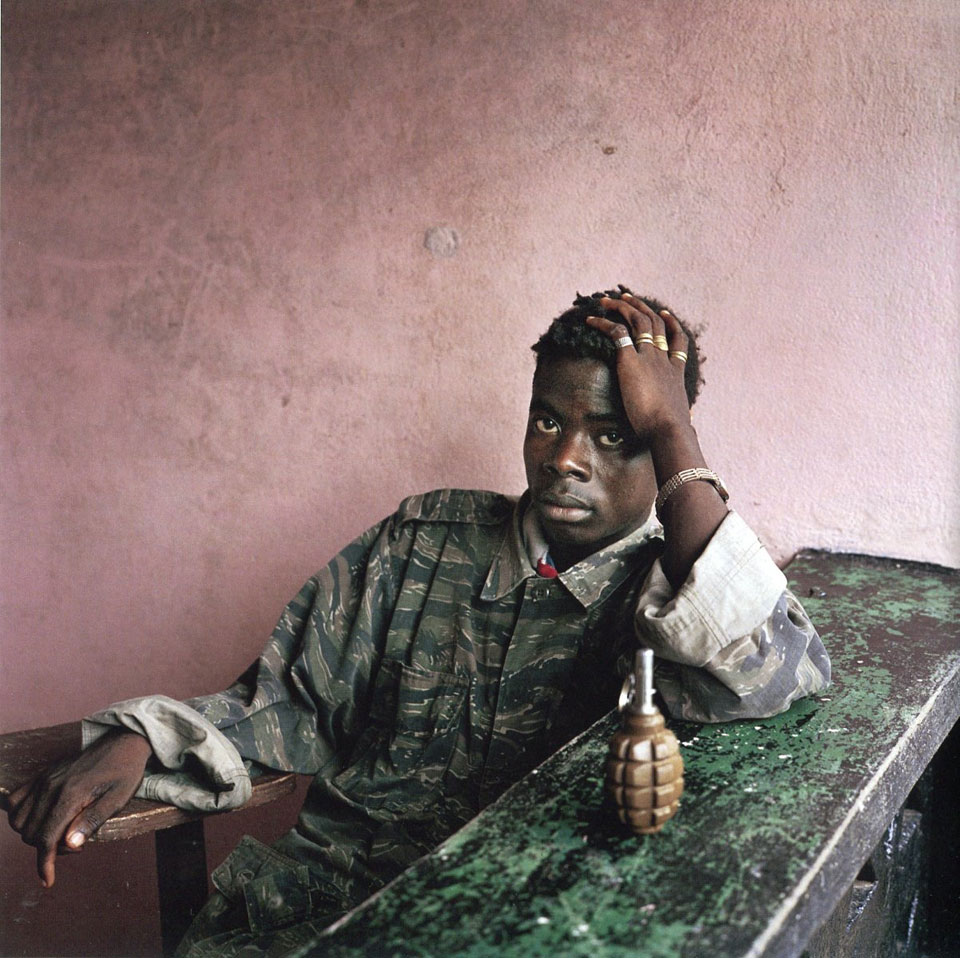

His modest ambitions were easily surpassed because it was not long before Hetherington was working in West Africa. While documenting Liberia’s 2003 civil war he was one of the only western journalists to travel behind rebel lines as they pushed across the countryside on their way to attack the capital city Monrovia with the goal of overthrowing the despotic president Charles Taylor. Hetherington’s video footage makes up a significant portion of the film Liberia: An Uncivil War and his book Long Story Bit By Bit: Liberia Retold was recently published by Umbrage Press. Both projects are important contributions to the post-colonial history of the region.

Liberia may not occupy much space in the collective consciousness of the U.S. but their narratives are intimately linked. Perversely, Americans have a somewhat provincial attitude toward slavery; it is our original sin, a psychic wound that never seems to heal. No doubt we are still haunted by the consequences of that Peculiar Institution but its ramifications leaked far beyond our national borders. Liberia is a legacy of slavery, founded by freed blacks in the early 1880s. The repatriation of ex-slaves to Africa was seen as an answer for both abolitionists and plantation owners who feared that the presence of free blacks in the north would inspire rebellion amongst those still enslaved. The capital Monrovia is named after the fifth president of the U.S. and although barely three percent of the population is descendant of slaves the conflict between them and those who identify as indigenous Africans remains an underlying tension in Liberian society.

Famous war images have their iconic drama, but Hetherington is not interested in what might be called the Robert Capa model in which the photographer attempts to distill conflict into a singular dramatic image. Instead he believes in the cumulative effect of text and images to address the shifting complexities of history unfolding. Long Story Bit By Bit presents oral testimony from perpetrators, victims and witnesses that anchor the often-disturbing imagery. We are introduced to altruistic Liberians and monsters such as Pastor Joshua Blahye, or General Butt-Naked as he was known during wartime, a character so self-aggrandizing that it would be comic were it not for his unspeakable cruelty.

Hetherington used medium format cameras loaded with color negative film, a very idiosyncratic choice in our digital age. The resulting images are simple and compelling, rich in detail and careful in composition; even the more gruesome images are thoughtful rather than exploitive. As promised by the book’s title, the photographs portray a society dissolving bit by bit, where atrocity and sublime beauty exist side by side. Hetherington slows down the unfolding apocalypse to image wild-eyed child soldiers and nattily dressed politicians, graffiti inscribed on the walls of looted government buildings, bodies by the roadside, young men with amputated arms, citizens fleeing mortar shelling, Monrovia at dusk, and a misty jungle landscape. There is a heartbreaking image of a young girl, fearful resignation marks her face as rests her hands on her chest, her delicate, sacrificial figure bracketed by her interrogators, a young man with a ‘Too Young To Die’ T-shirt and the rebel commander known as ‘Black Diamond’ sporting a leopard print coat.

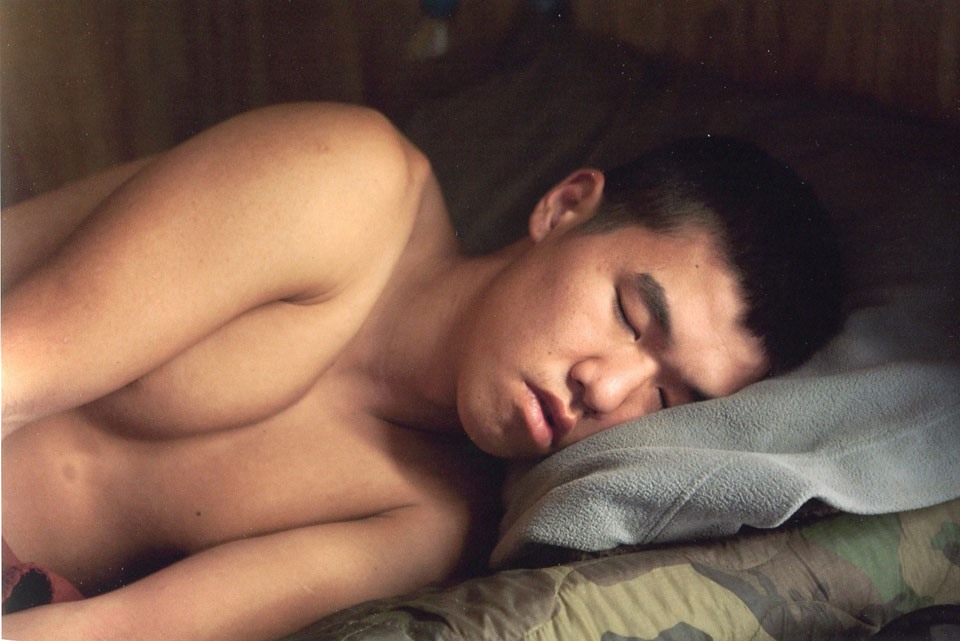

Hetherington believes that documentary photography is depleted in its traditional form. This is not some theoretical conceit but an acknowledgment that the production and distribution of images is rapidly shifting. It is not enough for a photographer to make the pictures; considerations of who has access and how images are experienced must also be addressed, an image-maker must find new audiences and new forms of presentation. A primary example of this approach the installation Sleeping Soldiers initially presented at the 2009 New York Photo Festival. Consisting of three adjacent screens, Sleeping Soldiers is a sensual, visceral, emotional and psychological immersion in both still and moving imagery gathered while Hetherington was embedded with a marine unit fighting in the remote Korengal Valley in Afghanistan. The central motif is a series of photographs of young men with heads upon pillows, tucked into their cots, often embracing themselves in slumber, faces temporarily free of anxiety, terror, grief or boredom. Meanwhile the sounds and images of battle; helicopters overhead, puffs of smoke in the hillside, the rattle of machine guns, build in density to clog the dreams of the dormant warriors. When the fragmented triptych finally resolves into a full-length image of a soldier stretched across the three screens, echoes of the dead Christ resonate. With its montage of violence, grief and slumber, Hetherington has created a contemplative space that exists somewhere between the meditative still image and the agitation of movement, between documentary reality and subjective truth.

While working in Afghanistan, Hetherington developed a collaborative relationship with fellow Vanity Fair contributor Sebastian Junger, author of The Perfect Storm. Together they shot, edited and produced the feature length documentary Restrepo that will premiere at the Sundance Film Festival in January 2010. Restrepo purposefully avoids explicit politics, does not feature interviews with generals and politicians about geopolitical strategy. Instead it focuses on ‘one platoon, one year, one valley’. Hetherington and Junger describe the film as entirely experienital from the point of view of a small group of soldiers deployed in one of the most dangerous, barren and unforgiving outposts in Afghanistan. The film is unflinching, unsentimental, and serves to remind us that no matter what our politics, we are paying the taxes that inserted these young soldiers on this hostile mountaintop and as citizens we ought to acknowledge that terrible responsibility.

Despite the countless treacherous situations he has survived and tragedies he has recorded, Hetherington does not consider his photographs the macho souvenirs of personal daring that serve to reiterate the myth and the cliché of the heroic war photographer. Bristling at generalizations of the photojournalist as some privileged outsider, Hetherington believes it is necessary to give oneself over to the moment, to be completely open physically and emotionally in order to make an honest image that somehow begins to portray the almost incomprehensible moments that constitute lives in crisis. Heroic or not, it seems inevitable that observing human cruelty would be spiritually damaging. A passage from Long Story Bit By Bit, describes a Liberian woman as having a ‘twisted moral compass’ from the ghastly things she had seen and suffered. One wonders if this might be also applied to Hetherington himself. He struggles with concept of a benevolent force in the universe, suggesting that like James Joyce, he tends to think that God might be ambivalent about his creation. Regardless of God’s mixed feelings, Hetherington understands that it is important to communicate the difficult things of this world if for no other reason then as a gesture toward a shared humanity.