Ron Jude

Ron Jude was born in Los Angeles in 1965 but was raised in rural Idaho. If geographical happenstance influences or even determines sensibility, then this American duality, between the urban and the rural, between the land of images and the landscape of a mythic individualism, permeates Ron Jude’s imagery. He makes no direct proclamations with his work; the cumulative power is subtle and observant, befitting a sensitive kid growing up among car guys and fur trappers. Proving that these are not mutually exclusive attitudes, his approach to photography is democratic and nuanced, utilizing found photographs, landscapes, portraits, and even pictures he took as a teenager.

He has been exhibiting his work widely for twenty years with solo exhibitions at Gallery Luisotti in Santa Monica, the George Eastman House, the Everson Museum, the Laurence Miller Gallery, and the Boise Art Museum. The Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago recently organized a survey of his three Idaho projects in the exhibition Backstory. He co-founded A-Jump books and has published several books of his own work including Alpine Star, emmett, and Lick Creek Line.

This interview took place on September 22, 2013 on the steps of PS1 during the New York Art Book Fair.

MAD – Could one recognize a Ron Jude photograph, the way someone might recognize a Robert Adams, a Gursky, a Linda Conner, just to pull some names out of the hat?

RJ – Probably not. There’s a consistent visual tone to what I do when I go out into the world and take pictures, but not in the stylistic sense that I think you’re referring to. I think you could take a cross-section of my images and identify them by their tone but that’s a more nuanced thing than style. That’s what I was trying to do with my recent zine piece Fires—bring these disparate things that I do together in a way that identifies that tone and makes an argument for a consistent attitude that goes beyond style. So, no, but yes, if you look closely and consider the context as well as the individual pictures.

MAD – You started your own imprint A-Jump Books in 2006 with your wife, the photographer Danielle Mericle. Why did you go into publishing photo books?

RJ – I had a book called Alpine Star that I wanted to publish back in 2005, and I took it to Andrew Roth for advice and he said, “This is an artist’s book, you should publish it yourself.” I had no idea how to do that, so I did some research and figured out what it took to get started. I got a bootleg copy of InDesign from my friend Roe Ethridge, who had just self-published his book Spare Bedroom and he sort of coached me through the basics of doing a book layout. Then I found a printer, which, as crudely printed as the book was meant to look, was far more complicated and expensive than you might think, mostly because the original images were rendered in half-tone and to avoid moiré pattern I had to use a specialized process called stochastic printing. I learned a lot about making books by self-publishing Alpine Star, mainly because I was too cheap to hire anybody to help me figure it out. Just prior to going to press, over dinner one night, Danielle and I decided it might be nice to create an identity for the book and we came up with A-Jump Books. The A-Jump was the big Olympic-size ski jump in the town where I grew up in Idaho. It was the jump the one that everyone was afraid to go off.

MAD – Which spoke to your fear of this new adventure?

RJ – (Laughter) Exactly. Danielle had some book ideas too, and in case I wanted to do another one, or friends who needed books to be facilitated, we thought it would be good to have an identity. So we’ve slowly expanded—Danielle and I have both done a couple of books with A-Jump, and we’ve done a couple with Nicholas Mullner, and a few other people—ten titles in total. We love the process of making books, but we’ve never had grand ambitions to be publishers.

MAD – On the website you describe A-Jump’s mission, in part, ‘to challenge convention through understatement…” Can you elaborate on that?

RJ – The idea for our imprint runs against the grain of any business model, we want to publish books that are thoughtful and quiet and are not necessarily going to have a big commercial appeal. We’re interested in books that are a little stubborn, occasionally difficult, but thoughtful… and hard to sell! (Laughter)

MAD – Well, this is an odd reference but when I read that I thought of the film genre ‘Mumblecore’

RJ – I don’t know what that is.

MAD – Mumblecore is a sub-genre of independent film that uses extreme understatement and naturalism as a reaction to bombastic and formulaic storytelling. I think there is something a little bit mumblecore about what A-Jump is doing.

RJ – That sounds exactly right, I think I might adopt that term and put that on the website (Laughter)

MAD – You cite the influence of Ed Ruscha’s early photo books 26 Gasoline Stations and Various Small Fires; can you talk about the difference, as you see it, between a photo book and a book of photographs?

RJ – Yes. It used to be the case that a lot of photography books deemed publishable by major publishers fell into the category of ‘books of photographs’, where you have recognizable and even iconic images sequenced in a book and were marketed and sold on the quality and appeal of the individual photographs themselves. Photo books incorporate a sense of narrative or a conceptual arc and don’t rely as much on the popularity or recognizability of particular images, although I wouldn’t say these two things are mutually exclusive.

MAD – In a lecture you gave in Rochester as part of a symposium on the photo book you talk about your initial encounter with John Gossage’s book, The Pond. You claim that this book baffled and then educated you to a new way of seeing and presenting images, and describe one image as a ‘picture of nothingness’. Which is an interesting phrase for a medium that is essentially descriptive.

RJ – The Gossage book was an anomaly at the time it was published in 1985– I’m not sure people knew what to make of it, particularly because it was published by Aperture. I was 20 years old and I was used to conventional photography books. I was the TA for the History of Photography professor and it was my job to make slides from all the new photo books coming into the library. So I encountered the Gossage book in this way and I couldn’t understand why this work warranted publication, it didn’t contain any individual ‘great photographs’ as I understood the term. It wasn’t until wrestling with it for a while that I understood that he was creating a visual narrative, moving through negative and positive space in the landscape in a way that depended on the subtlety of sequence and close reading. He was using pictures as raw material to serve a larger purpose. I loved it because it challenged me to understand photography in a new way.

MAD – So instead of confirming your expectations of what a book of photographs did, it confounded them, tested your limits….

RJ – Yes.

MAD – The first book you published with A-Jump Alpine Star is essentially a sequence of images clipped out of your hometown newspaper called The Star News. These are vernacular images made without esthetic intention that suggest a collective unconscious of a small town. You’ve talked about the influence of Gossage and Ed Ruscha, but I was wondering if you were at all influence by Sultan and Mandel’s book Evidence and also Lesy’s book Wisconsin Death Trip?

RJ – I was definitely aware of both books when I made Alpine Star but not intimately aware of them. I didn’t own either of them, so I knew ‘of’ them more than I knew them. People do make those two references to Alpine Star frequently. They’re great examples of gathering somewhat arbitrary images and putting them together to make a new thing, but to be honest I was not thinking of them in any way when I made Alpine Star which is a kind of fictionalized depiction of an actual place. You used the word ‘vernacular’ and that’s really accurate. You don’t usually think of journalistic photographs as vernacular, because it’s such a specialized field, but most of the photographs in this newspaper weren’t taken by professional photographers, they were taken by the writer, or people who live in the town send pictures of events they attended, or their vacations or things they did that weekend and the newspaper will publish those. It’s like an early version of Facebook, a way for the town to share its news with itself. Vernacular photographs that are being seen in a public forum. So that’s the attraction, these images have no artistic or refined documentary intent. They could be easily manipulated by the sequence you put them in.

MAD – In thinking about the role of photography in conceptual art, one of things that was useful was photography’s ‘affectless-ness’. Photographs appeared neutral or without authorship and could be made in a way that did not betray the artist’s intention.

RJ – Yes, but when you’re studying photography in art school what you’re told to do is to ‘find your voice’, to create authorship and that’s what I learned to do. I was always interested in the conceptual uses of photography but it’s hard to unlearn that impulse toward creating an image that’s recognizably yours. There’s an appeal to photographs that don’t have authorship because they’re so fluid, you can do so many things with them.

MAD – Yes, exactly, but that sense of ‘affectless-ness’ has become a style in much contemporary photography. (Laughter)

RJ – Absolutely, If you go inside and look around the book fair at the zines and publications by younger photographers you see a lot of, well I don’t want to call it ‘bad photography’, but it’s a style that doesn’t mind looking amateurish or unconsidered. In that sense, paradoxically, that anti-style has become almost a polished affect.

MAD – In that same lecture in Rochester you talked about the space between what photographs promise to deliver and what is actually communicated.

RJ – It’s a natural expectation to think that photography should deliver information about the things we’re looking at in the picture. And because that image is usually a highly edited slice, more often than not it shifts the meaning away from the thing pictured, toward something else. There might be an entirely new narrative that you bring to the picture, or it could communicate misinformation. So even if we know better, we have an innate expectation for photographs, but often they deliver something else entirely. That tension between expectation and what actually happens is where all the fun is. You can utilize photography to generate different narratives and through the sleight-of-hand of sequencing, you can redirect attention away from what the original subject may have been.

MAD – I understand how that might work in sequencing images for a book or putting an exhibition together but does it actually affect the way you make photographs in the world? Does that sleight of hand thing you are talking about influence your choices or function as a kind of subtext while you are photographing?

RJ – Not in an overly deliberate manner but making books over the last 6-7 years has changed the way I make pictures, I feel that I don’t have to completely identify or pin down why I’m making a picture in that moment. I’m looking at it as making more raw material to put into the bucket, so to speak, and later on I can piece it together into something else. It doesn’t inform the kind of picture I make, it just allows me the freedom to make whatever picture I want to make in that moment based on whatever impulse I have, knowing that later it will likely serve some other purpose.

MAD – I remember in undergrad school and even to some extent in grad school, one had to develop a personal style, your own way of looking at things and that’s useful but at a certain point it would become predictable – this guy documents garage interiors, or this one does random portraits on the street, so you wouldn’t take certain pictures because it didn’t fit into your own style. In effect you would censor yourself because that potential image didn’t look like what you already did. In retrospect it seems kind of crazy, I think about all those pictures that weren’t taken.

RJ – I know what you mean but I never employed that kind of self-censorship. I knew that what really mattered was what people ended up seeing, what I chose to print and put on the wall or into a book or whatever. I would tell myself “I can take this dumb picture—nobody has to see it, and maybe it will make sense in some other context in 20 years”.

MAD – I want to go back to your idea about the space between what we expect from a photograph and what it delivers. Do you think this implies some fundamental inadequacy in photography? And if so, do you think this is a kind of academic argument. I understand the critique of photography, what John Tagg called the ‘burden of representation’ but whether it be cell phone ‘selfies’ or pictures of Syrian atrocities, don’t we still depend upon and indeed love, respect and need photography for what it can deliver of the real world, as partial, subjective and episodic as it may be?

RJ – I agree. When I talk about the space between our expectations and what actually happens it is kind of an academic point, but my goal in making books or shows is not academic. I think the real power to a successful photo book is not found in the academic point, but in our very real need to look at pictures to help us sort through our ideas about the world, and that is much more of a visceral thing. So the point may be academic, but the experience is not.

MAD – Let’s talk about your book emmett. I wouldn’t say it’s inscrutable but it’s very mysterious in the way that only the very familiar can be mysterious. You employ repeating motifs that in of themselves are accessible and even mundane, like car racing, landscapes, images of a young man who judging by his hairstyle may have been taken in the 1970s or 80s. But first let me ask ‘Who is Emmett?’

RJ – Emmett is a town where the drag races were held, about an hour and a half away from my hometown of McCall, Idaho, which is where all these projects take place. The kid in the pictures is named Ken, he was a high school friend of mine, a motorhead, very into GTOs and car races and he took me along to the drag races one day, which is when I took all of those pictures. For some reason I took a lot of photographs of him, he wasn’t my best friend but I have far more pictures of him than I do of anyone else from that time. Doug DuBois claims I was in love with him.

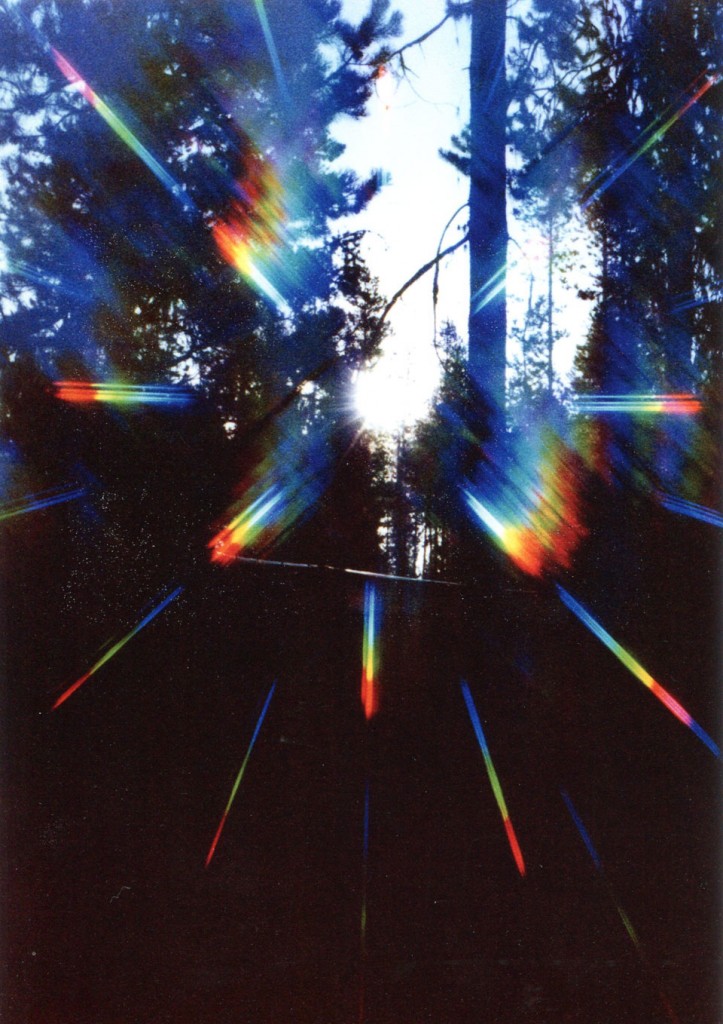

MAD – For some reason the book reminds me a little bit of Twin Peaks. It’s an enigmatic narrative taking place in a small town and some of the pictures even have a star filter on them, like some kind of low-rent surrealism.

RJ – It works nicely in that way. At the time I took those pictures I was an advanced amateur enthusiast in photography and was just beginning to take classes, and my teachers were telling me to throw all those tacky filters away. All of the pictures in Emmett were taken at that time, and although some of them are quite naïve, some of them I like quite a bit, and not for ironic reasons. I couldn’t take most of those pictures now, I know too much. (Laughter) With those images I can look back at the circumstances of my life but also at my life as a young artist.

MAD – I know, when I was a teenager learning photography, I had no artistic intent, except for an occasional failed attempt to mimic Edward Weston, I just took pictures of my friends and family and they have become really valuable to me. But when I went to art school, for years I made terrible pictures trying to push the medium and didn’t photograph my friends and family hardly at all, which is something I regret now.

RJ – I started looking at these images again when I went home to visit my mom and she had all these pictures I took in spindle-wheel photo albums. Initially, I had an idea for a little zine, but the more I started digging, the more I found. I was amazed at the richness of the material, and it eventually became a full-fledged photo book. I approached it almost like Alpine Star, in the sense of working with found photographs. So many of the pictures I don’t even remember taking—it was if I was working with an archive that just happened to be mine.

MAD – I wanted to ask you about maleness and masculinity in your work. The first work I knew of yours was about 20 years ago, close-up photographs of businessmen on the street…in Atlanta?

RJ- The project is called Executive Model and started in Atlanta but I also photographed in Chicago, New York, San Francisco, all over the place.

MAD – Yes, I was doing my performance project men of the world at the time, for which we posed as businessmen on the streets of those same cities, enacting odd gestures and actions. I saw your pictures and thought we had a lot in common in terms of the performance aspects of maleness.

RJ – There was a performance aspect to that project, maybe not so much in the pictures but in the fact that I was my following these men around anonymously.

MAD – A big part of those pictures is the idea of male self-presentation, the uniformity and coding of the apparel. In regards to the history of photography I thought of Harry Callahan’s pictures of women on the streets of Chicago and I also thought about Robert Longo’s Men in the Cities large-scale drawings from the late 70s.

RJ – I was aware of Longo’s work but was not trying to replicate it. I was more in the street photography mode, trying to do something new with that genre that wasn’t Garry Winogrand, but something else that added a bit more of a conceptual basis for the work. Of course I knew who Harry Callahan was but I wasn’t aware of that particular work until later. But coincidentally, Harry Callahan came to see the Executive Model show in Atlanta and was very complementary, so that was a great moment for me.

MAD – I think the underlying thread of maleness is present in the more recent work, like Emmett or Lick Creek Line, if a bit more obliquely. So, excuse me if this is too personal, but did growing up in rural Idaho, and what it meant to be a man in that environment, have a profound effect on you and the concerns in your work?

RJ- I’ve always been reluctant to talk about my work in personal terms, as if the autobiographical shouldn’t matter and is somehow strictly beside the point. But the older I get and the more perspective I have, especially on the earlier projects, it seems obvious that that is deeply what has motivated me to do much of the work. That said, I still maintain that although the work may be personally driven, it’s not necessary for the work to be consumed from that perspective. The audience doesn’t need to know me, even though everything from looking at men in their business suits in an urban environment to the fur trapper checking his trap line in rural Idaho was made, in some sense, in relation to who I was or who I thought I was. I think I used the motorhead kid, who was into drag racing, as a kind of surrogate for myself, although I wasn’t like him at all. I was the sensitive kid who liked to ski, which was as close as I ever got to sports, and I was never into cars in that way. The idea of what it means to be male is present in all of that work. What I was trying to get at exactly, besides my curiosity, I’m not sure. But I’ve typically always framed my work with a conceptual agenda rather than an autobiographical one.

MAD – I don’t think the autobiographical and the conceptual are mutually exclusive.

RJ – I think you’re right, and that element is clearly present in the work, but out of my desire not to muddy the waters or direct attention away from my central concerns, I didn’t want to talk about it that way. I wasn’t interested in the confessional, and I’ve never thought of my life as interesting enough to be the central subject of the work. And I was never really interested in social/political critique as a basis for making work, so the identity politics aspect of ‘maleness’ wasn’t something I was trying to engage.

MAD – To pay attention to something is to acknowledge its importance. So the presence of this underlying thread of maleness in your work is not necessarily a critique. It is observational.

RJ – I’ve been criticized for that though, for not taking a stand, for not critiquing. But yes, it’s more observational, a simple curiosity about what things might mean, and some have understood that to be non-committal. But when you’re curious, it’s hard to commit. Commitment to a critique implies a full understanding of something, and my starting point for making work has always been my lack of understanding. Critique also places you on the pulpit in relation to your audience. I don’t feel comfortable on the pulpit. I’m not a moralist.

MAD – Well, there are times when as citizens we have to take a stand, to commit to a cause, but as an artist I am against the critique. I am not interested in the explicit in art. There are many exceptions to that obviously, Goya, Heartfield, Kollwitz, Golub, Ai Wei Wei. But generally I really don’t care about someone’s opinion on a particular topic. I care about how an artist connects to the world, how they express their enthusiasms and follow their curiosities and obsessions. In the realm of the observational or the contemplative, it is important to let things be. Of course opinions, esthetics and ethics are all wrapped up in the things artists make, but for me if a critique is the major function of the work, I find myself, more often than not, terribly bored. The critique is so easy; it’s so easy to critique maleness and who is going to argue with you except the most Neanderthal?

RJ – Yes, so much much critique that happens in contemporary art is very ‘reasonable’ and your audience, to a large degree, will probably agree with you. How is that interesting? If I’m looking at something, I want to empathize, regardless of my relationship to that thing. Fur trapping, for example—I think it’s a pretty tough thing to look at and very easy to object to, but it’s part of someone’s world and that world is probably just as rich and full of contradictions as anybody else’s. The more interesting questions have to do with that person’s circumstances and their history and what has led them to this activity. That’s the confusing complexity of things in the real world; there’s a moral struggle of reconciling the difficult thing you’re looking at with empathy for your subject, and that’s what’s interesting to me, to feel that conflict.