Dana Hoey

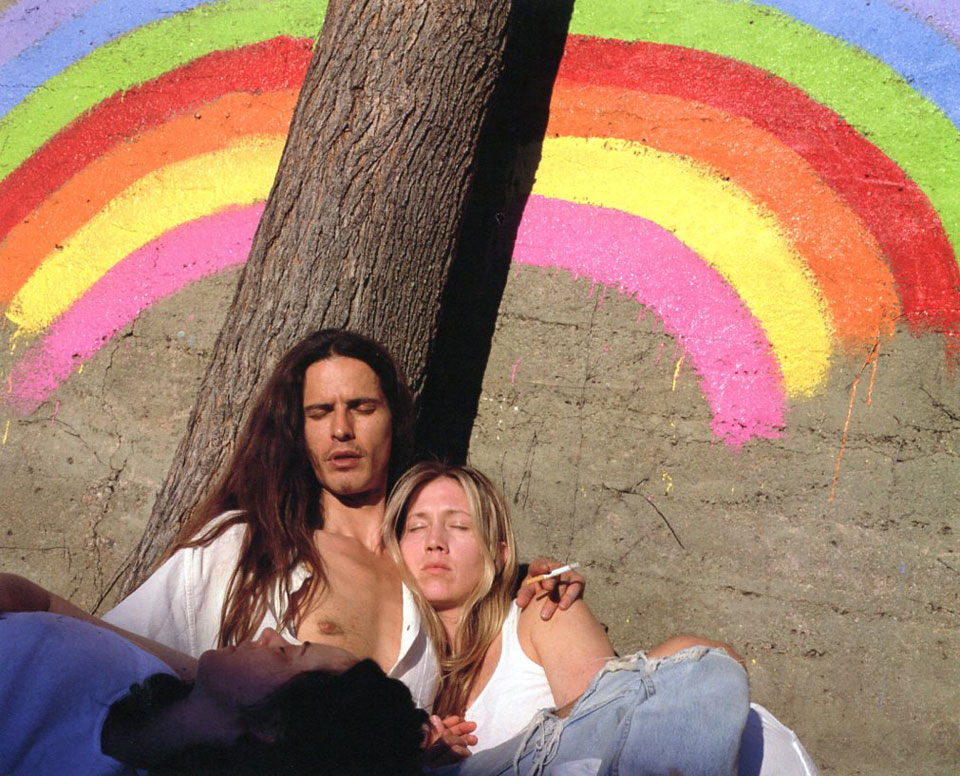

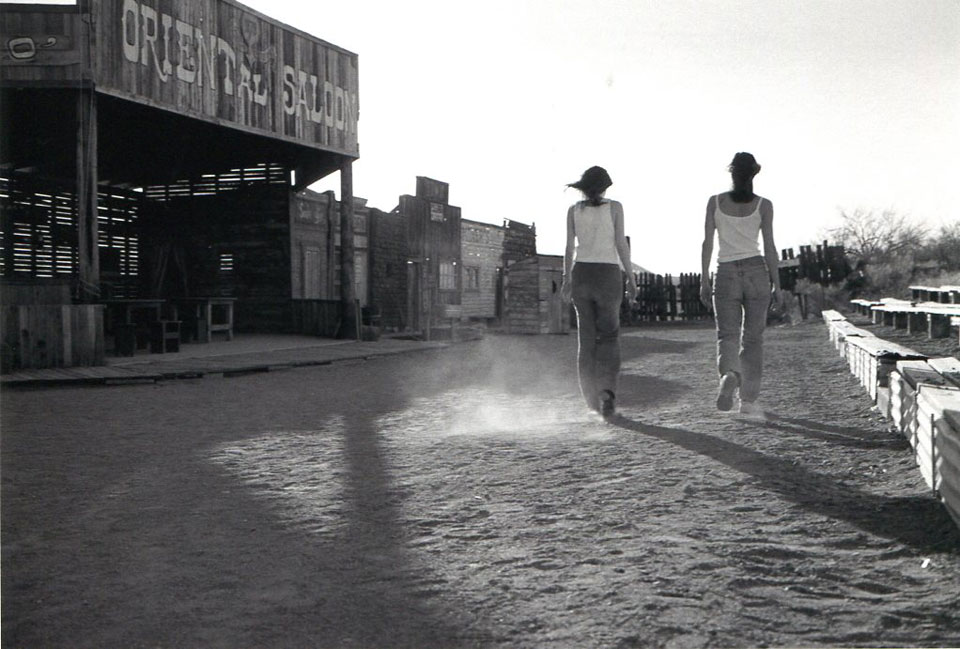

Born in Northern California, Dana Hoey now makes her home in upstate New York. She shares her cottage / home with her husband, the artist Oliver Wasow, their two children and various goats, guinea fowl, donkey, dog, cats, and the many hummingbirds flitting about the porch. I first heard Hoey talk about her work when she gave a lecture at Syracuse University in the late 1990s. I found her work to be, and still do, funny, unexpected, familiar yet strange, with underlying tensions between cruelty and tenderness. When viewing a photographer’s work, one can often find traces of a lineage of influence – the heroes, and relevant contemporaries. But with Hoey, it’s not so obvious. One might see traces of Cindy Sherman for example, but I think her influences might be more literary, cinematic and commercial. Echoes of the ‘buddy movie’, that Hollywood genre in which a couple of guys bond over danger and adventure, can be seen in Hoey’s black and white photographs from 1999 that feature two young women in a variety of scenes in a Western Landscape. While some of Hoey’s pictures seem to fit in with the narrative tableaux photography of the 1990s, others seem like stock imagery that might be used to sell feminine hygiene products or prescription drugs to alleviate depression.

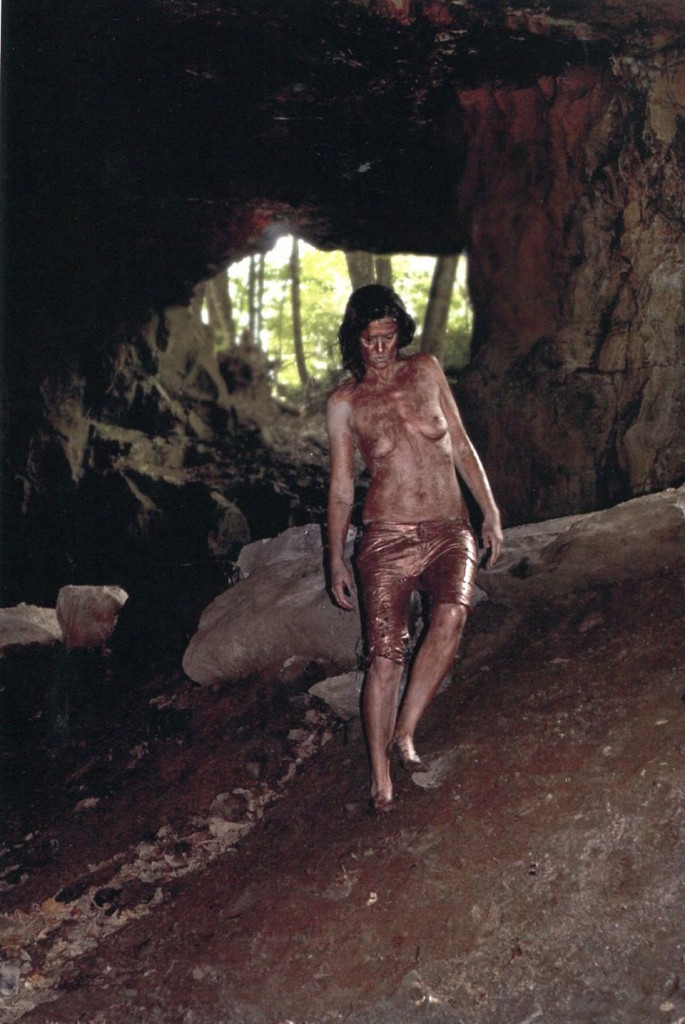

I think this might be what confounds viewers most, Hoey does not pander to our expectations of what a ‘good’ art photograph looks like. She mixes the styles and rhetoric of different genres to produce offspring that are accessible yet utterly enigmatic. Her project Experiments in Primitive Living (2005-08) is epic in its scale and subject matter. Made in the apocalyptic atmosphere of post 9/11 and the imperial blunders of the Bush war machine, Experiments in Primitive Living imagines life after some final disaster. The images are haunting and work in complex relation to one another. Some are humble signifiers, such as the peony sprouting from the ashen ground, while others seem to quietly but deeply resound with a terrible sublime. Hoey’s stories (if they are stories) stay with me because they are resistant to easy interpretation, they are not gratuitously difficult, but instead test my unexamined limitations with grace and fierce intelligence.

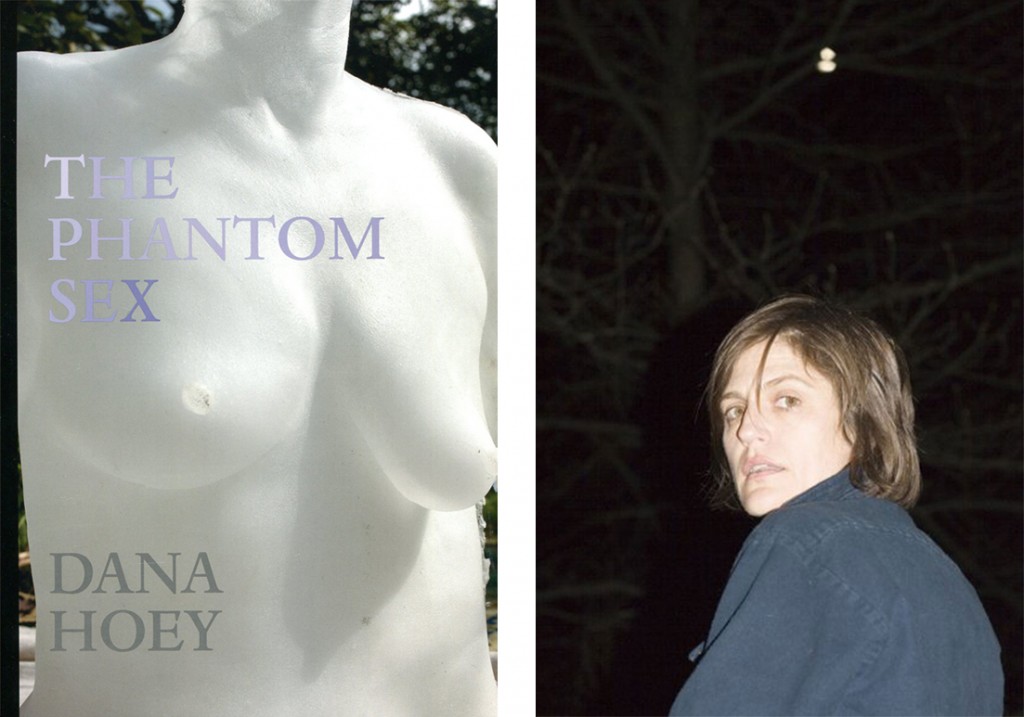

Hoey is represented by Petzel Gallery. In 2012 the University Art Museum at SUNY / Albany presented her mid-career retrospective The Phantom Sex. This conversation took place in Hoey’s studio in Upstate New York, July 2013.

MAD – I want to ask you about your recent catalog The Phantom Sex which is a kind of survey of your work. I did not see the show, but I understand that it was not hung chronologically, but instead associatively. Can you talk about the decision not to hang the work ‘in order’?

DH – The catalog was made for a mid-career survey show at the Albany University Art Museum (The actual project The Phantom Sex was in this show, and also shown that year at Petzel Gallery, New York). The least ordered part of the exhibition was the figurative 1990s work. The way I worked, I’d have a thought, like “Women don’t get along, let me make a fighting picture” and then “Women do get along, I’ll make a helping picture.” And then five years later “No women really don’t get along” and I’d make another fighting picture (Laughter). They weren’t made chronologically, so I thought they did not need to be hung that way.

My urge is always to be totally associative and non-thematic, but in photography people expect a certain kind of clarity. Twice I’ve been reviewed in the New York Times with the question “Why don’t we understand this better? Why doesn’t she make films?” I take great joy in refusing narrative, but I am also trying to get clearer as I get older. I don’t want to be withholding or solipsistic but I still want to very assertively refuse narrative.

MAD – But you are not refusing narrative by making abstract images, there are recognizable things going on in your pictures.

DH – Well you can’t really get away from narrative. Even abstract work has a narrative about how it was made.

MAD – I think that’s one of the strengths of your work, it implies so many stories yet remains very open, it doesn’t answer specific questions about narrative, except to suggest that our notions of what visual narrative can be are somewhat limited.

DH – When you have a particular sort of figure that repeats from picture to picture, it’s natural to make conclusions about how the pictures relate. There is something about photographs that leads people to want literal stories.

MAD – Was that your attraction to photography in the first place?

DH – My attraction initially was simply because I like looking at photographs. There was a blur between the images I was looking at as a young person and my actual life, because there are a zillion photographs of younger women. So I looked around at my friends and there was this blur between the photographs of women and their actual bodies. I wanted to recreate that blur but with little bumps of reality that I experienced and they experienced that might not be perceivable in continuous motion but in a still photograph that bump could be seen.

Narrative definitely has got me in its grips, I am always making up stories in restaurants as people walk in and sit down. “Oh there’s a hooker, she’s sitting down with a guy whose wife has died. I hope she’s nice to him” (Laughter). I completely believe my stories.

MAD – Do you try to listen in in their conversations to see if your story might be confirmed?

DH – Well I don’t want to get caught, I’m usually thinking pretty nefarious things.

MAD – Whenever I am at a restaurant with my mom, we’ll be sitting there and I talking and she is nodding her head and vaguely looking in my direction but what she is really doing is listening to the conversation at the next table, because apparently they are way more interesting than me. So I just give in and mumble ‘So what are they saying mom?” and she’ll burst into whispering account of every detail and then attempt to surmise the nature of their relationship. (Laughter)

MAD – Initially the models in your photographs were your friends

DH – Yes, I used my friends because there they were ready and willing. I loved them; often they were interesting to look at and looked great on film, not always in a conventionally beautiful way. It sounds so naïve now but once I got my friends on film the allure of pornography was always sucking at the picture. It became clear that the nude pictures sold a lot more than the others; I realized that I’d turned my friends into representations for sale about sex. They were walking pornifications, and therefore I was too. None of which I cared to fight directly but I do view it as an interesting condition of my and my friend’s existence. Now that I am older I see it not so much in my immediate life but in the lives of younger women.

MAD – As you stated, some critics have wondered why you haven’t made films, but you do have a couple of videos on your website. One of them is called One Pro, Two Amateurs which is a mud-wrestling video and I was thinking about porn while watching it. You are off camera and can be heard directing the behavior of the women wrestling with each other. Did you make that in response to your observations of what you called ‘pornification’ of your images?

DH – At the time I felt that I and some other young women photographers were dealing with being consumable ourselves. I also felt pushed to make work with a quasi-lesbian hook, that is fake lesbianism for straight porn. This irritated me. So I dialed all sexuality down for a while but then I got angry, I did not want to take the sex out of the work just because the pictures with the pretty girls were selling better. So I decided to make work completely in the thick of the problem. The reason it is titled One Pro, Two Amateurs is because one of the women is a retired porn star. She seemed so old to me and now I am older than she was when I made it. And she had also done pro wrestling, so I wondered what would it be like if we literally reversed the cultural power of youth and age, respectively, and women had to depend on physical power. It was also interesting because while they were wrestling the older woman, the “pro” kept trying unsuccessfully to position my friends in more suggestive, sexual poses. Later she made me wrestle her and she just dropped me on my head. (Laughter)

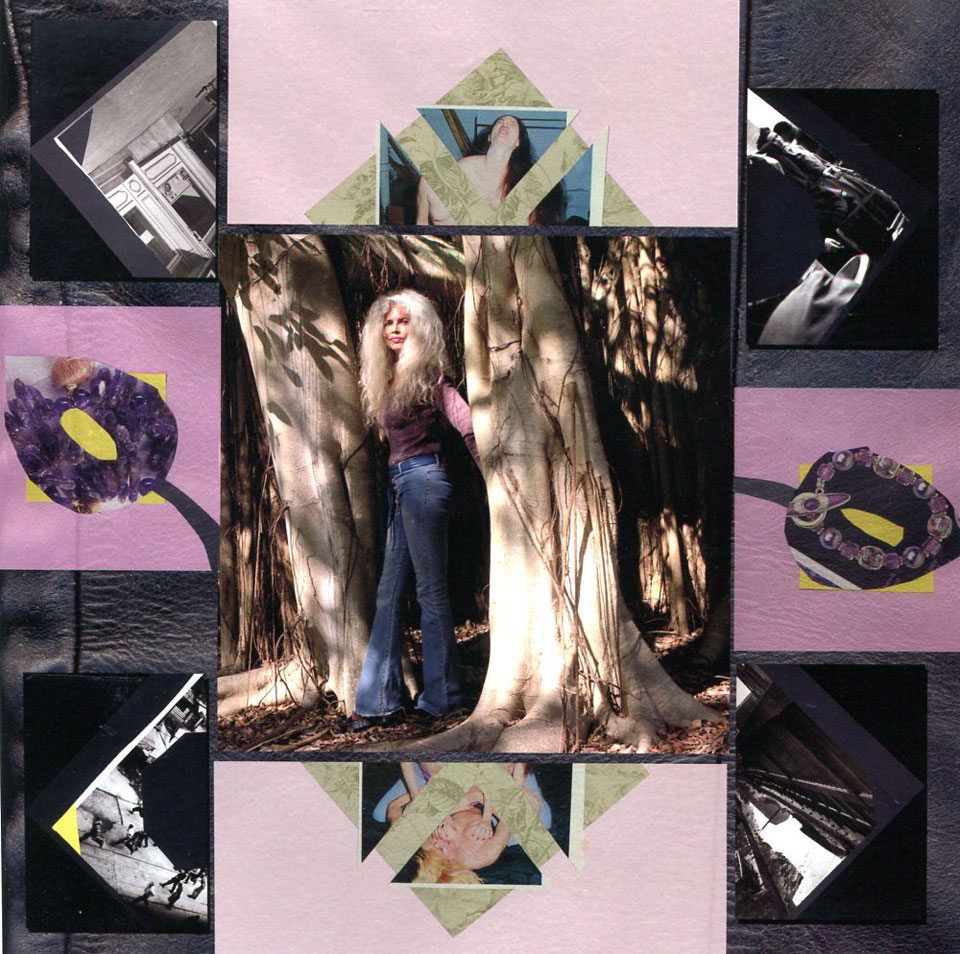

MAD – I wanted to ask you about the Pattern Recognition pieces, which are quilt-like and very much unlike most of your other work.

DH – Those came right after One Pro, Two Amateurs and in some way they are connected. They are collages of pictures I shot and pictures that I found. In local newspapers in Woodstock and Hawaii, I advertised for ‘Silver Foxes’, women who were over sixty who had long silver hair. I ‘liked’ the pictures I made with a small ‘l’, but I was too frightened and respectful and making respectful pictures of older women did not feel entirely accurate to my feelings, but I didn’t want to hurt their feelings or abuse their trust in any way, but they needed to be contextualized. I have this cat fighting porn collection that I chopped up and put with the images of the women in a quilt. So I put the sex with them without making them participate directly.

MAD – And what about this one with the men?

DH – I know! I broke my own strict rule of no men in my pictures. I didn’t like the victim strain in feminism, so I had this rule that I wouldn’t even address the ‘man problem’ (Laughter). The images are executive portraits and they are just so temptingly superior looking.

MAD – I have been rethinking Robert Heinecken recently for a couple of different reasons. Next year MoMA is doing a retrospective. I knew Robert and worked with him. In the late 1990s and early 2000s I also did a project with the Center for Creative Photography where his archive is held that resulted in the publication Robert Heinecken: A Material History. He was such an interesting man of my dad’s generation, this hard-drinking, womanizing, wannabe ‘Rat Pack’ charmer. He was a fighter pilot in the Marines who became a kind of hippie-artist-intellectual who started the photography program at UCLA and had a tremendous impact on photography as an art form in the 1960s really up through the early 90s. His work was practically canonical until the 1980s when the post-modern wave in conjunction with the feminist critique, kicked him to the curb. He was deliberately written out of the histories….

DH – So painful….

MAD – Yes, I always thought it was unfair, obviously there are problematic things with the work but he didn’t deserve that excising from history. One of the things he was criticized for was his use of pornographic imagery, cutting up and reassembling female bodies and reveling in that kind of naughty objectification without sufficient theoretical defense. I mean, I think he was interested in photography’s relationship to commodification but I also think he truly reveled in these ‘sexy pictures’, and made no apologies for it. So your work here, these ‘Pattern Recognition’ pieces are so different in terms of that the fact that they were made decades apart and your subjects are older women. But I wonder if they were a kind of rejoinder or response to Heinecken?

DH – For me, it’s not about being on the right side of feminism per se. Many people hated my mud wrestling video because they perceived it as anti-feminist. I think feminism is a broader road than saying we can’t have sex and we can’t objectify. I’m more interested in the descriptive road, and it my particular narrow view on the experience of being objectified. I am who I am and of a certain generation but I would never want it to be anti-Heinecken, I love that work. However I am a female so when I see a picture of a naked woman I think of them more as a person than some notion of a sexualized female, because I know what its like to be perceived that way – as porn and as an actual, dimensional human being.

MAD – Were you thinking about that work in any way?

DH – Not Heinecken, no, but I was talking to my dealer, Friedrich Petzel and he pulled out this Cindy Sherman book, you know that picture of the old lady doll with the dildo in her? He pointed at that and said that you can make pictures about this kind of thing but they have to be harsher than this if you want me to sell them. Instead of making the images harsher I made them gaudier and embarrassingly craft-like. To me that was harsh, to make them feminist in such an extreme clichéd way to where they would be sickening. I love craft-based feminist art but it also embarrasses me completely.

MAD – So how did people react to that piece?

DH – If I had showed them three or four years later they might have been more in step with what people were interested in terms of collaging photographs. I think most people were appalled (Laughter). It was the equivalent of bad painting in a way. I love Friedrich, he totally got it. They didn’t get reviewed, and god, nobody bought them but they have had an afterlife, being shown here and there in group shows on collage or feminist issues.

MAD – Speaking of Cindy Sherman, one of the essays in your catalog talks about how your generation of young female photographers emerging in the 1990s, were bridging the divergent impulses of Nan Goldin and Cindy Sherman. I guess I can see that but it seems like an after-the-fact observation. Did you feel that you were making that connection at the time, when you were a student or soon thereafter?

DH – I’m going to answer you by asking a question. Who is that turn-of-the-century Boston photographer who made the quasi-sexual, occult-y self-portraits, melodramatic images of crucifixions in the woods…..? F. Holland Day!

MAD – Oh, yes, early 20th c. platinum and gum bichromate images, nudes and religious scenes. James Crump did a book about him.

DH –I saw myself loving and bridging New Objective German photography and that kind of Pictorialist staged melodrama. I wanted to see what it would be like to put two totally contradictory things together in a photograph. Over the top subjectivity together with utterly dry seemingly objective material. I love Cindy Sherman, Jenny Holzer, Laurie Simmons, they were all my heroes in college and I was actually taught at one point by Nan Goldin. She was my hero too; I worked for her. I mean she is so committed to direct photography she would actually cry when students made staged work. But I love her, I was broke and she gave me a job, what can I say?

It’s easy to take the people who influence you for granted. I guess I would have to say that Laurie Simmons was a huge influence on me. I love Cindy Sherman’s work so much but she is in her own work (although she operates as a cipher) – that is so not what I want to do ever. I can’t relate to that aspect of her practice. But the clarity of the ‘Film Stills’, the way they just drew a line between photography and culture was mind-bending for me. And it’s not just about the appropriative gesture like Richard Prince but the fact that you could re-state the appropriative gesture. But by the time it got to my generation I think those gestures were more buried. I thought of myself as working in a commercial mode or painterly mode.

MAD – The first time I saw your work, I think what I found most confusing or challenging was that echo of the commercial world. I don’t think that wall had been broken yet, I mean Christopher Williams was doing that, but it was rare. There was still this notion of binary between ‘fine art’ photography and commercial or utilitarian photography. Of course the history of photography is full of people who had vital careers in both arenas, but generally they remained separate worlds with photographers doing commercial work to subsidize their art practice.

That commercial ‘look’ of your photographs created a kind of emotional distance for me, I found them initially hard to access. Your work challenged my pre-existing notions of what tableaux or narrative photography should look like.

DH – John Szarkowski kind of said the same thing about my work when he was a visiting critic at Yale – he didn’t understand it but it seemed to be drawing on commercial photography.

MAD – I am interested in that alienation, if something makes me feel uncomfortable because it does not fit into easily identified categories, I want to know why.

DH – Did you figure out why?

MAD – I think because it did not pander to my expectations.

DH – Well if it looks like commercial photography it must pander because that’s what commercial photography does. (Laughter)

MAD – My expectations for art. My first photographic hero was Robert Frank; subjective melancholy is my habitual way of seeing. Although I am not saying I cannot appreciate or love work that is conceptual or wry.

DH – I have a bleak, melancholic take on things, its just a little angrier and a lot more female.

MAD – Cumulatively I see that more and more in your work. There is darkness, anger, violence…..

DH – Well….. (Laughter)

MAD – I just mean that we live in a very fucked-up world that is asymmetrical in terms of wealth, power, opportunity…..

DH – There’s two things about it. One is that I did not want the work to be simply navel-gazing that I see in a lot of self-reflexive feminist student work that focuses on their bodies and so quickly becomes narcissistic. I mean there are wars going on, so I don’t want my work to seem ignorant of the world. The second thing is that, although a lot of women disagree with me, I just don’t believe in any of the supposedly essential characteristics of femaleness that are ascribed to me. I have had kids, I know boys are different from girls, but I hate biological arguments. I don’t experience life as the female I am told I am, in any way. Girl aggression is terrifying and subliminal. But I think aggression is useful energy and necessary in the world. So that’s my soapbox; don’t throw away your aggression, Ladies! (Laughter)

MAD – In your project Experiments in Primitive Living, I was thinking about Cormac McCarthy’s book The Road.

DH – How could you not? There were two things that defined that decade – 9/11 and that book.

MAD – Yes, and for lack of a better term, while I was reading it I was thinking about the ‘patriarchal post-apocalypse’. The narrative is without an essential female character. The mother disappears early on and the father and son journey through the wreckage of the world. It is so bleak, all of history has been erased…..

DH – It’s a totalitarian gesture………

MAD – Experiments in Primitive Living is bleak but it is also not without its small moments of beauty, and even hopefulness, it doesn’t feel cruel or final. It’s difficult to compare your photographs to a novel or a Hollywood movie but your work is less broadly drawn, there is nuance in the aftermath of devastation. The world you create is strange and unexpected, bleak but not without its mysteries.

DH – Well in those pictures the ‘bleak’ is over. I think it’s a little bit evil to wish for the erasure of the entire world. I don’t wish for it but to imagine beyond it is to wish for it in a way. I felt I had been making political work and I wanted to make pragmatic work. Experiments in Primitive Living is organized in sections and each section had a pragmatic image, or a suggestion as to the way to proceed. Like the image of the canned food. I don’t know how many people actually learned how to purify water by looking at my pictures but its there. To describe it as a friendlier version of The Road is to buy into a certain feminine perspective that I don’t……

MAD – I didn’t describe it as friendlier. What I am saying is that it is more nuanced and complex than this patriarchal fantasy of wiping everything and everyone out except for the father and son. There are a lot of strange and disturbing things in your pictures that I am afraid of but things are coming back, so I wasn’t trying to essentialize.

DH – Well, there is a danger of essentializing since it’s a sci-fi feminist fantasy implying that most of the men are gone so the president is this old lady, another old lady represents the police force. There is a picture of a young man wearing a long-haired wig so he can pass as a female. I don’t have a separatist fantasy although at times my work looks like that; I was just trying to get a glimmer of what it would look like if women were in charge.

MAD – This may seem like an odd thing to say but it goes back to my earlier comment about being challenged by the look of your pictures. Sometimes I think of the ‘wrongness’ of them, that how you photographed something is inexplicably wrong somehow…..

DH – You so busted me (Laughter). That’s exactly how I think about them. I think to myself while making a picture; ‘What would be the wrong thing to do here?’

MAD – Well, I am not saying that about every picture (Laughter) but there are certain images that jump out at me and exclaim their wrongness, like this mini van picture, it goes against the grain. Some artists who want to make dark and uncomfortable pictures might employ expected or cliché means, like graininess, or high contrast and dark shadows, or creepy environment or even blood and viscera. But to be made to feel uncomfortable by this seemingly normal almost generic image of a woman in a pink jumpsuit coming out of a gray mini van, that’s special! (Laughter)

DH – I like discomfort. But the bottom line is – is she laughable or is she heroic? It’s a bit funny, is she just a normal citizen of the world or is she an insane old lady in a pink velour sweat suit? I want it to be both.

MAD – There is an iconography of what a heroic or even a successful dramatic photo might look like and this image falls outside of that in both ways. This is again how I find your work confounding expectations. Or this image of a radio from the Experiments in Primitive Living series, it could be an eBay picture. I know that you often work in clusters of images, so its difficult to separate a single image from what is to be seen in relation to a group of other. But there is a certain audacity in the image in how it challenges the conventions of fine art photography.

DH – I have friends who have been to fancy photo schools who lecture me that I should be using a view camera, but with something like that it has to have a kind of crappy quality.

MAD – One of the things that might distinguish a dilettante from a true artist is the willingness to do something deliberately wrong or contrary to expectations. People try so hard to learn how to make art and then spend their careers parroting or paying tribute to whomever they think is a master. So when I first saw your work I thought to myself ‘You can’t do that’ and even though I have been looking at your work for well over ten years sometimes I still feel that way. (Laughter) But then it sits with me and I feel as if my perception of what photographs look like and what they can do has been stretched.

DH – That’s the best compliment I ever had (Laughter), makes me feel like a participant rather than a gardener, donkey shit shoveler (Laughter).