Taryn Simon

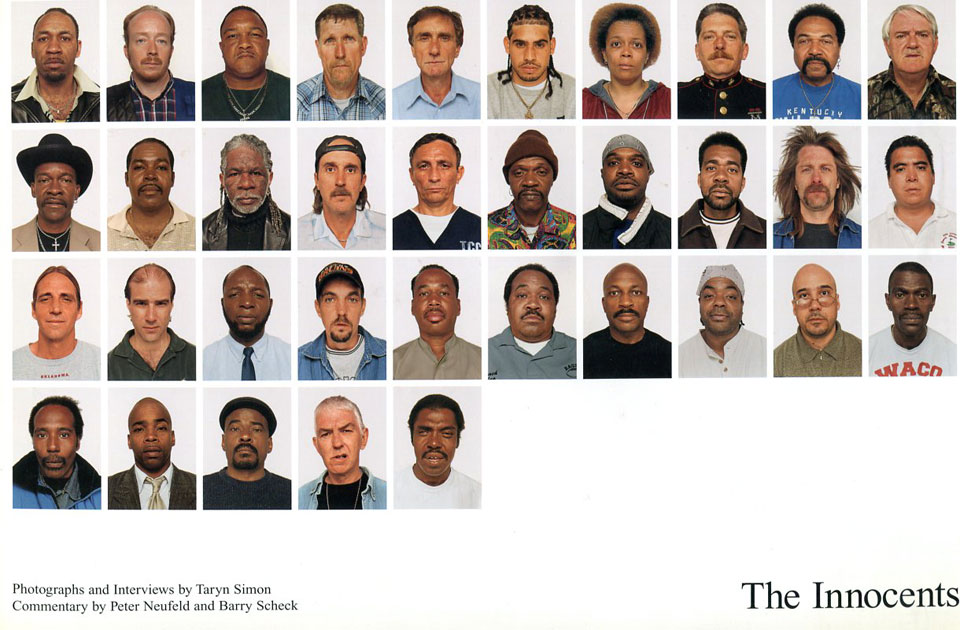

Taryn Simon was born in New York in 1975. Her photographs challenge the conventions of documentary photography by grafting astute political observation with explicit theatricality. She has published several books including The Innocents that documents the victims of wrongful conviction, and An American Index of the Hidden and Unfamiliar, a survey of inaccessible and obscure sites that reveal fundamental truths about American culture. This interview was conducted in August 2007, in New York City and published in Dear Dave, magazine #2.

Since that time, Simon’s work has produced new works including A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters I-XVIII and Contraband, has mounted significant exhibitions at numerous galleries and museums including the Museum of Modern Art, the Tate Modern and the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin, and published several new books including Contraband and Birds of the West Indies

MAD – How did photography become important to you?

TS – Growing up, my father worked for the government and traveled often; he was a prolific and avid photographer. He had closets with endless shelves of his Kodachrome slides. He would give slide shows accompanied by the history of wherever he had been.

MAD – Was that something you dreaded or did you find it entrancing?

TS – I loved it. I loved him. He was larger than life and attached the wildest stories to everything from the simplest landscape to military operations in Thailand during the Vietnam War. I’ve recently gone back and looked at those pictures and while they are formally great, they are for the most part, conventional travel documentary photographs. But my memory is of crazed magic.

MAD – Was he a photo geek who knew everything about lenses and films?

TS – Yes. He had every filter, film, light, new gadget. He had the first video camera. He would walk around with this enormous machine and lights, filming and directing everything. He gave me a camera early on and we would go out and take pictures. My grandfather was an equally obsessed nature photographer.

MAD – I am thinking about that scene in the film Fanny and Alexander when the kids are projecting the lantern slides, and Bergman pictures their glowing faces and wide-eyed expressions of wonder.

TS – But not in such swanky surroundings.

MAD – So looking at and taking pictures accompanied you as you grew up.

TS – Never in any studied form. But it was certainly the hobby of choice for the men in my life. Early on, I would set up photographs – construct small stages outdoors to image objects in. There is a priceless series of my grandmother wrapped in a satin sheet in a field at night with horrible lighting – we’d do a lot of death scenes. I continued on from there. I have probably dipped into every obvious stage of photographic evolution.

MAD – I guess at some point you became ‘educated’ about photography, was it at Brown University?

TS – Brown didn’t have a photography department, but through a lottery you could get into classes at RISD. The opportunity is sought after and luckily my name was picked in my first year. I convinced my photo professors to allow me to exceed my credit limit so I took classes through my four years at Brown.

MAD – What did you study at Brown?

TS – Ah, Art Semiotics. Which is pretty painful to admit but it was the one thing that completely confounded me, so I had to conquer it.

MAD – Has it proved useful?

TS – Yeah, but I haven’t made sense of it.

MAD – I’ve heard you speak about the importance of the public arena for your work. Your photographs appear in books, magazines, museums and galleries, and have been embraced by both journalistic and fine art venues, which puts you in some pretty rarified company. I’m wondering how the work changes for you depending on the site.

TS – In my works I always think of the book and the exhibition as very distinct entities. I don’t see them replicating or shadowing one another, they are defined and shaped separately. This is the ideal setting for my photographs: one in which I dictate the context. When working in a journalistic vein you don’t have complete control, and with my work, which is committed to a very defined context, that can be difficult. For this reason I don’t do magazine work except for occasional portraits for the New York Times. These commissions are often to photograph something I could never access on my own, like photographing the president of Syria. It offers me opportunities I wouldn’t otherwise have. But ideally I would love to always only work for myself.

MAD – I’m thinking of Susan Meiselas and how she came to do the Nicaragua book – as a way of correcting the record in a sense – by putting her photos in a narrative, political and esthetic context that was more true to her experience than how the photos were used in various magazines she worked for. You spoke to some of these concerns already – so this awareness of how one’s own photographs can be misused is why you avoid situations where your photographs might be compromised politically?

TS – I obsessive about it, probably to my detriment. When my images are used in any press context, I’m careful to preserve their intentions. I try to check what other images and text will surround the work and I make sure that the text is always attached to maintain that relationship as a ‘piece’, because its not just a photograph but a photograph in a context.

Taryn Simon, ‘The Innocents’

Charles Irvin Fain, Scene of the Crime, Snake River, Melba, Idaho. Served 18 years of a death sentence.

MAD – What does the term ‘eyewitness’ mean to you?

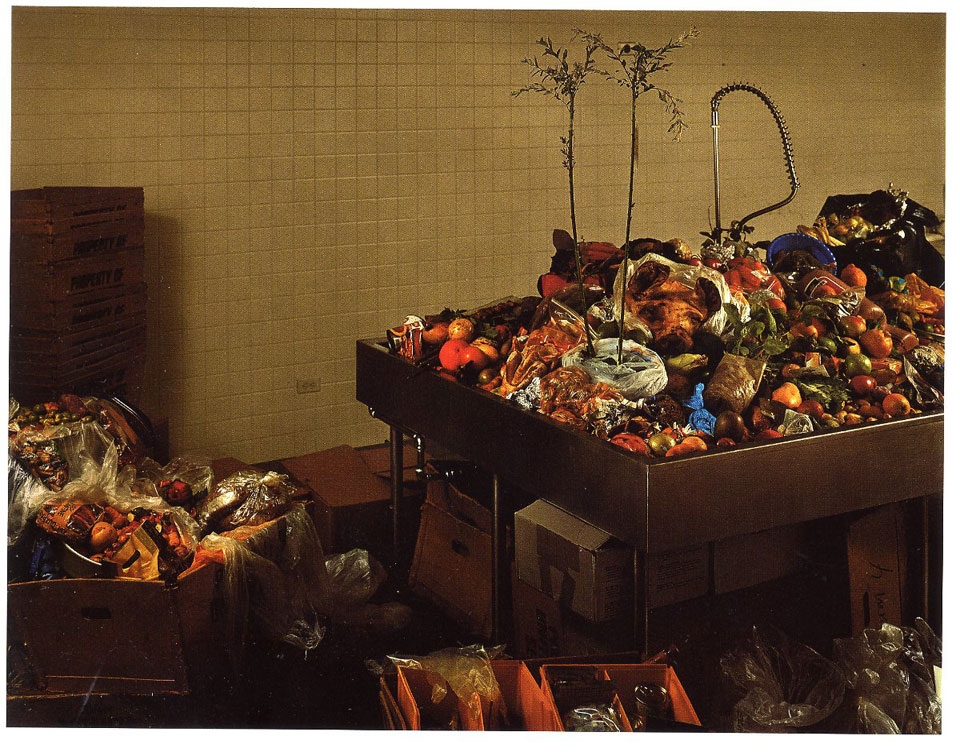

TS – The Innocents studies and speaks to eyewitness fallibility, so why would I consider myself a reliable eyewitness? That’s where work like mine potentially differs from traditional documentations of political subject matter. There is a very specific intervention in nearly all of my photographs where I am altering the scene or making some sort of esthetic adjustment to make it more seductive. It documents reality but very admittedly changes reality and doesn’t pretend to harness the truth. In The Innocents there is an ambiguity or conflict between the site and the subject and in American Index you can see formal interventions in which I am rearranging what is before me. For example, in the JFK Airport contraband room I was very aware of making a photograph that was going to refer to an early painting. I spent hours arranging the fruit and vegetables to construct a specific palette, moved the pig’s head to the right place, arranged the plant just off center in the frame. I didn’t arrive to that scene; I arrived to a huge mountain of crap on a basin that didn’t have any sort of seductive shape.

MAD – In that case, did you have to convince the authorities to allow you to intervene physically in that material?

TS – Not there. Many times I have battled for permission but here they handed me gloves and a mask, to protect against disease, rot and rancid smells, and let me attack. They thought I was nuts and enjoyed watching.

MAD – Being thought of as nuts can sometimes be useful, allowing a kind of freedom.

TS – I was their spectacle for the day.

Taryn Simon, ‘An American Index of the Hidden and Unfamiliar’.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection, Contraband Room. JFK Airport.

African cane rats infected with maggots, African Yams (dioscorea), Andean potatoes, Bangladeshi cucurbit plants, bush meat, cherimoya fruit, curry leaves (murraya), dried orange peels, fresh eggs, giant African snail, impala skull cap, jackfruit seeds, June plum, kola nuts, mango, okra, passion fruit, pig nose, pig mouths, pork, raw poultry (chicken), South American pig head, South American tree tomatoes, South Asian lime infected with citrus canker, sugar cane (poaceae), uncooked meats, unidentified subtropical plant in soil. All items in the photograph were seized from the baggage of passengers arriving in the U.S. at JFK Terminal 4 from abroad over a 48-hour period. All seized items are identified, dissected, and then either ground up or incinerated. JFK processes more international passengers than any other airport in the United States.

MAD – Last night I was watching the video interviews you conducted with some of the men pictured in The Innocents. I was struck by the anger and tragedy in their voices – and the incredible range of emotions animating their faces. And I wondered about your intentions with the video, because it is a document of such a different order. In your book the tone of the photographs is somewhat reserved, elegant even. Did you make the video because it does something that the images and texts do not?

TS – It’s in direct opposition with the photograph’s methodology. In a photograph, because the absence of voice I always choose (and it’s also a matter of taste), I show the distance between me and the subject in the photograph. Some criticize the approach as cold and without emotion when I am dealing with something so loaded – there is a kind of iciness to them. It’s purposeful because I don’t ever want to pretend that I have access to what that person has experienced or is experiencing. I like that to be very evident in the photographs. I intentionally shot the video in such a raw form, which helps the author almost fade away.

MAD – There are a variety of strategies that photographers use to image and dignify other people’s tragedy. It struck me that you use the term ‘iciness’ to describe your distance, but I think that’s too severe a term because the very act of your being there is a gesture of acknowledgement towards your subject’s singularity. So without resorting to melodrama, the lack of sentimentality in your photographs is a sign of respect towards their experience.

TS – That’s the point. But what I find in film and in photography is that there are two schools of thought: there are those who are moved through reserve, and there are those who need to have the emotion declared in a very pronounced form. The notion of respect is also built into my approach technically. I use camera equipment, lighting and very elaborate set-ups that would typically be reserved for celebrities or presidents.

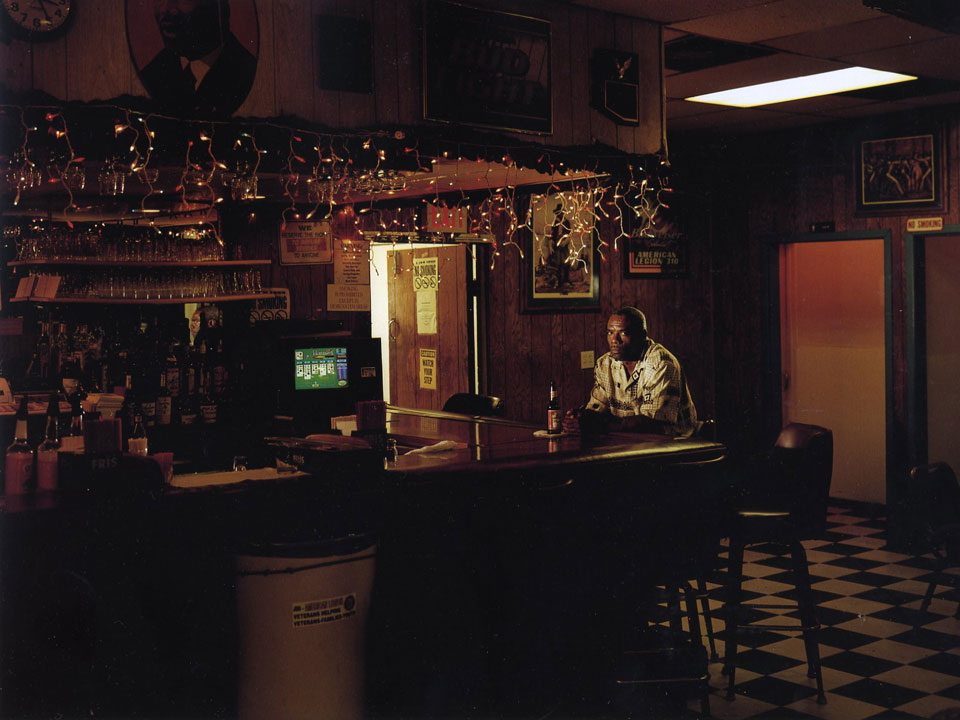

Taryn Simon, ‘The Innocents’

Frederick Daye, Alibi location, American Legion Post 310, San Diego, California.

Served 10 years of a life sentence.

MAD – You photograph the men and women in The Innocents in one of four places: the scene of the crime, the site of the arrest, the site of misidentification or the place of the alibi. How did you arrive at those choices and who decides where to take the picture – you or your subjects?

TS – After some initial failures I realized I needed to set up very specific margins for myself and that was to restrict the images to the sites you just mentioned. Ideally I always wanted to use the scene of the crime because that was the most complicated relationship – this site, which they had never been to, had changed their lives forever and I could play with truth and fiction in a very direct way. But many of the subjects were uncomfortable visiting the scene of the crime because they did not want to have any familiarity with it. Even though they had been exonerated, they feared it would be used as evidence of guilt. So I had to look at other sites that would still have the gravity and complexity I was looking for yet was OK with them. What continually amazed me was that most people still lived very close to where these events had taken place, so it was never hard to bring them to the sites to be photographed.

MAD – Tell me about the structure of An American Index of the Hidden and the Unfamiliar and who wrote the text that accompanies the images.

TS – The texts are a collaborative effort between me, my editor Althea Wasow, Aliza Waters, and my sister Shannon, who was also the producer of this project. While at the sites I interview personnel and experts. It’s later a process of culling, researching and fact checking. We then put it together in an unauthored style that is meant to read like an encyclopedia – cold, uneditorialized facts. The book and idea of the index was modeled after early books of discovery in which explorers of the new world recorded their findings of fauna and plant life through elaborate drawings and descriptive, scientific text. America is changing. There is a sense of discovery in An American Index: unearthing a new political, ethical and religious landscape.

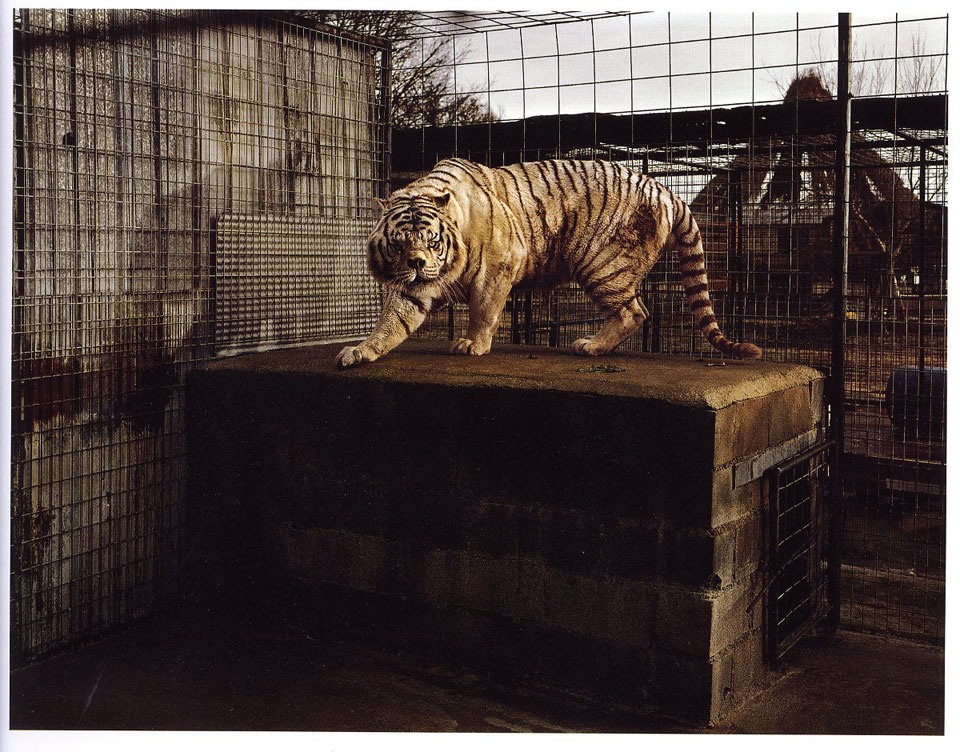

Taryn Simon, ‘An American Index of the Hidden and Unfamiliar’

White Tiger (Kenny), Selective Inbreeding. Turpentine Creek Wildlife Refuge and Foundation, Eureka Springs, Arkansas.

In the United States, all living white tigers are the result of selective inbreeding to artificially create the genetic conditions that lead to white fur, ice-blue eyes and a pink nose. Kenny was born to a breeder in Bentonville, Arkansas on February 3, 1999. As a result of inbreeding, Kenny is mentally retarded and has significant physical limitations. Due to his deep-set nose, he has difficulty breathing and closing his jaw, his teeth are severely malformed and he limps from abnormal bone structure in his forearms. The three other tigers in Kenny’s litter are not considered quality white tigers as they are yellow coated, cross-eyed and knock-kneed.

MAD – I like what you write in the introduction to The Innocents: ‘I saw that photography’s ambiguity, beautiful in one context, can be devastating in another.’ In a sense you are describing in contemporary language the conflicted duality that has fueled a hundred year old argument about photography as a political tool versus the camera as an instrument toward art. The devastation of ambiguity in The Innocents is the devastation of the individual wrongly convicted. In the case of An American Index, you rely on ambiguity, at least initially, for the pictures to seduce the viewer.

TS – The viewer comes to the pictures in An American Index without immediately knowing what they are looking at, especially in an exhibition context where the text is less visually prominent. They are intentionally abstract – the process in which the image and its definition unfold is part of the work, there is a play between the image and its text. One approaches the works esthetically, then reads the descriptive text, then returns to the image, which is now viewed in a more defined state, then returns to the text and understanding evolves. The initial ambiguity or abstraction is stronger in the exhibition. With the layout of the book, which is familiar, there is a promise by its very structure that you will come to understand; there is simultaneity in the perception of word and image.

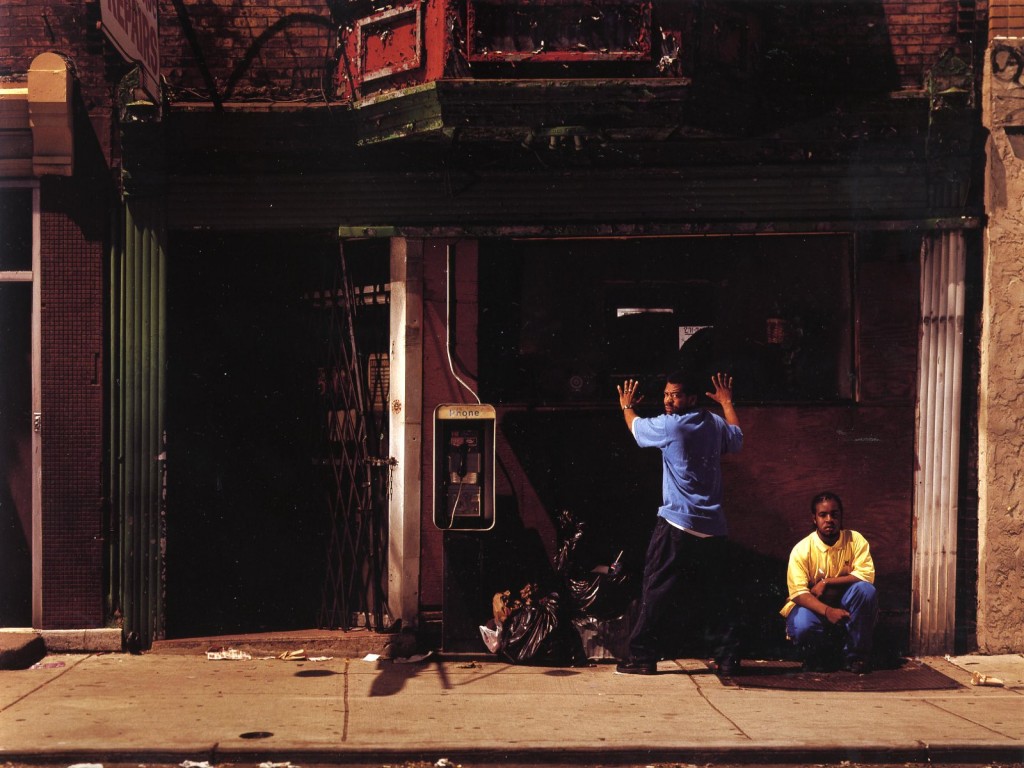

Taryn Simon, ‘The Innocents’

Larry Mayes, Scene of the Arrest, The Royal Inn, Gary, Indiana.

Served 18.5 years of an 80-year sentence.

MAD – The manner in which you use artificial light, especially in daylight, seems particularly strong. In some images the shadows appear thoroughly opaque and there is an almost singed quality to the sunlight. Artificial light can be a self-referential sign of the presence of the photographer and as you use it in The Innocents it can be an isolating tool or suggest interrogation, which adds a real edge to those pictures.

TS – I see the lighting in The Innocents as very different from the lighting in An American Index, and that reflects my own personal evolution as a photographer. The light in The Innocents was used in an exaggerated form to separate the subject from the background, and that quality of light repeats throughout the entire project. The burnt palette that you’re talking about is something that I have always been personally attracted to; it’s not necessarily a conceptual decision. Whereas in An American Index, the light was site-specific and was not used in such a hot form. I was looking for a softer, smoother, more ethereal, almost religious structure to the light. I wanted the pictures to have an apocalyptic feeling and that was largely achieved through lighting. In pictures like the great white shark in captivity, the cryopreservation unit, or the Death with Dignity Act, I was trying to create a visual equivalent to white noise with the light where you feel an incessant underlying presence in the photograph.

MAD – You worked on An American Index for four years. How did you even begin to look for what is ‘hidden’?

TS – I would start by making lists: lists of sites I personally wanted to investigate and lists of categories that needed to be represented to create noticeable entropy. Many of these sites were imagined as I was seeking that which had no defined or popularly distributed visual anchor. It’s not difficult to identify the inaccessible; the difficulty was to find sites and subjects with a twist, some strange malformed relationship to the idea of what is hidden. And it’s not just about what is difficult to access. NASA was going to let me into the innermost cavities of the Space Shuttle, their most private corridors, but I wanted to photograph the beach house where astronauts spend time in quarantine with their families just before they blast off into space. This little barbecue shack was the antithesis of what you would expect from the high-tech culture of NASA and had a lyrical quality that wasn’t alive in the classified areas harboring the latest technology.

Taryn Simon, ‘An American Index of the Hidden and Unfamiliar’

Cryopreservation Unit, Cryonics Institute, Clinton Township, Michicigan.

The Cryonics Institute is a non-profit, member-run corporation which offers cryostasis (freezing) services to individuals and pets upon death. Cryostasis is practiced with the hope that lives will ultimately be extended through future developments in science, technology and medicine. When, and if, these developments occur, members hope to be awakened to an extended life in good health and free from disease or the aging process. Cryostasis must begin immediately upon legal death. A person or pet is infused with ice-preventative substances and quickly cooled to a temperature where physical decay virtually stops. They can be kept in this state indefinitely. For an additional cost, Cryonics personnel will wait out the last hours of an individual’s terminal illness and immediately begin cooling and cardiopulmonary support upon death in order to limit brain damage. At present, the Cryonics Institute cryopreserves 74 legally dead human patients and 44 legally dead pets. It charges $28,000 for the process if it is planned well in advance of legal death and $35,000 on shorter notice. The cost has not increased since 1976 when the Cryonics Institute was established. The Institute in licensed as a cemetery in the state of Michigan.

MAD – I think one of the strengths of the photographs in An American Index is how they simultaneously reveal and question. The strangeness of what is pictured is not just about some private grotesquerie residing outside the realm of the normal, but is somehow deeply connected to the machinations of power, entertainment and spectacle in contemporary America.

TS – That comes alive in the cumulative effect of the pictures, the build-up of all of them working together. Such specific investigation and technical information is traditionally delivered in a very compartmentalized form. An American Index works against that isolation. I wanted very specific, not broad, research in security, government, nature, medicine, Hollywood and religion gathered within one cover. An American Index confronts the boundaries between the public and the privileged access and knowledge of experts.

MAD – In an interview with Charlie Rose he asked how you were different as a photographer now than five years ago, and you replied that you were more paranoid and mistrustful. That really struck me because you use photography to go to these darker places in an attempt, I assume, to understand and to witness. But the paradox is that in seeking engagement you are, in effect, further isolation yourself from the world. Is that accurate?

TS – Yes, I am a very fearful person. There is something in my photography or in the choices I make about what I photograph, where I am confronting limits so that they do not close in on me. And yes, it often has the reverse effect, making me hyper aware of what I fear.

MAD – You mentioned earlier that you were feeling at an impasse with photography. Is that related to that psychological trap?

TS – I am finding photography harder and harder. It is physically difficult to travel with the lights, the large format camera, and the negatives, but even more, I am increasingly frustrated with the margins of the medium itself, which is probably why I continually incorporate text into the work. There is so much effort behind each photograph yet it feels so damned disposable. That’s also the beauty of photography – it is democratic and ubiquitous but it’s also discouraging when the effort is so laborious and its life so fleeting.

Taryn Simon, ‘The Innocents’

Vincent Motto, Scene of identification and arrest, Philadelphia Pennsylvania.

Served 8 years of a 12 to 24 year sentence.

MAD – There has been a lot of hand-wringing over the last couple of decades about the ethics of photojournalism, the whole enterprise of picturing other people’s lives, who looks and who gets looked at. Has this growing mistrust of images in general had any effect on you as a photographer?

TS – The mistrust of images is at the foundation of everything I do and the reason why I use text. I chose to do The Innocents partly because it documents the phenomenon of the fallibility of images leading to someone potentially losing their life on death row. But at a certain point the critique of representation is an understood part of the general practice and is ultimately very boring and censorious when it prevents people from engaging the world through images or producing them. Every image is irresponsible when we dissect it; I go to great lengths to set up corrections. It’s important to keep the conversation alive, at the very least in political arenas, as it demands monitoring.

MAD – Salman Rushdie writes in his introduction to An American Index, “Democracy needs visibility, accountability, light. It is in the unseen darkness that unsavory things huddle and grow.” Is there a sense of secrecy in the culture right now that makes this work especially urgent?

TS – I want to see the mechanics behind everything; I want to see the cockpit and the pilot flying the plane. But knowing how things work, unveiling power structures, can be dream-crushing. Salman’s quote is correct – but the terrifying thing right now is that secrecy seems to grow even in the light. There’s a confounding indifference to exposure.

MAD – Tell me what happened when you tried to gain access to the Walt Disney archives. In lieu of a photograph you print their response to your request. Apparently you can get in to photograph glowing radioactive waste but if you want to see Mickey’s underwear, forget it.

TS – It’s the best part of the book. Disney denied me access to their underground facilities beneath the magic world, where the ugly innards of a heavily populated corporation live. Their faxed denial gave me the most poetic and perfect punctuation for the project. It was far better than any photograph I could have taken. The last sentence reads “Especially during these violent times, I personally believe that the magical spell cast on the guests who visit our theme parks is particularly important to protect and helps to provide them with an important fantasy that they can escape to.” And that’s how I felt about many of the photographs in An American Index, that I was seeing the cracks in the fantasy or the rhetoric or the mythology. There is a dream-crushing element to what I am doing and that is exactly what Disney wanted to avoid.

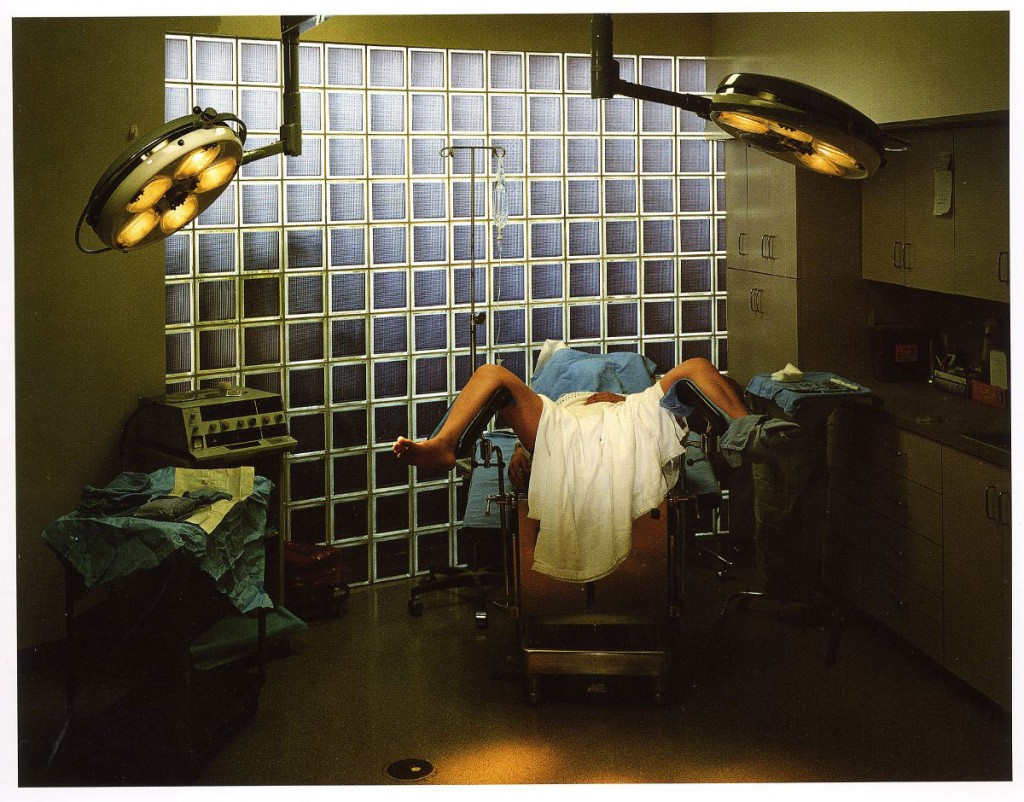

Taryn Simon, ‘An American Index of the Hidden and Unfamiliar’

Hymenoplasty, Cosmetic Surgery, P.A. Fort Lauderdale, Florida

The patient in the photograph is 21 years old. She is of Palestinian descent and living in the United States. In order to adhere to cultural and familial expectations regarding her virginity and marriage, she underwent hymenoplasty. Without it she feared she would be rejected by her future husband and bring shame upon her family. She flew in secret to Florida where the operation was performed by Dr. Bernard Stern, a plastic surgeon she located on the internet. The purpose of the hymenoplasty is to reconstruct a ruptured hymen, the membrane which partially covers the opening of the vagina. It is an outpatient procedure which takes approximately 30 minutes and can be done under local or intravenous anesthesia.

The hymen has not been proven to serve any biological function. Some girls are born with an imperforate hymen. Rupture most often occurs during first intercourse, but some girls tear they hymen during sports activities or as a result of injuries. The majority of the time there is a correlation between an intact hymen and a woman’s virginity; many cultures view the tearing of the hymen as a critical symbol of that loss. While similar attempts to alter the hymen predate modern plastic surgery, hymenoplasty is now just one of several vaginal cosmetic surgeries that are growing in popularity worldwide. Dr. Stern charges $3,500 for hymenoplasty. He also performs labiaplasty and vaginal rejuvenation.