Eric Gottesman

Eric and I were graduate students together at Bard College. His enthusiasm for life is contagious and his deep interest in others is reflected in his work. Collaboration is key to Eric’s image making process and his work develops out of his relationships with his subjects, research, a deep understanding of the context and political engagement. Eric worked with a group of children in Ethiopia called Sudden Flowers for over a decade to make pictures using collaborative techniques. He has also worked in Lebanon (where his mother’s family is from) and Jordan on projects about conflict, nostalgia and the trauma of displacement. Eric’s practice encompasses photography, text, video and most recently book translation and curating.

Eric laughs generously (a spontaneous laughter that makes others feel unfettered and at ease) so it is fitting that one of the Sudden Flowers productions was a laughing contest that Eric staged with Ethiopian children. The resulting video is haunting as it’s unclear if the child is laughing or crying. Cathartic or painful? Laughing at whom, what or in spite of what? Viewers may become uncomfortable with their own assumptions or expectations. Just as I’m compelled to think about the nature and enigma of laughter, I return to the particular individual represented. Although Eric is acutely aware of the specificities of his own viewing position, the complexity and poetics of his practice emerge from his openness to a vision that is different from his own. Eric’s work questions the tenets of collaboration, authorship and viewership, always complicating these questions further and never settling for easy answers.

Eric’s work has been widely exhibited including recent exhibitions at the Addison Gallery of American Art, the deCordova Museum and Sculpture Park and Amherst College. He has received a Fulbright Fellowship as well as awards from the Magnum Foundation, Apexart, the Aaron Siskind Foundation, Artadia, and the Massachusetts Cultural Council. A book of his work, Sudden Flowers: May The Finest In The World Always Accompany You, is forthcoming.

This conversation began in Eric’s studio and continued along the railroad tracks at Amherst College, where Eric was an artist-in-residence in spring 2012.

Eric Gottesman, ‘Konjit, Laughing Competition Finalist’ 2006. Photograph from video still. In collaboration with Sudden Flowers Productions

CMB: What an amazing studio space you have here! And it’s great to be seeing your new project Studio Karmen for the first time. How did you first meet Ahmed, the subject of this series?

EG: In 2006, I was invited to lead a photography workshop in Jordan. One of the students was Ahmed, an older man who dressed every day in a suit and was regimented in how he viewed photography. His questions during the workshop included: “What are the rules of photography?” and “How do you make a good picture?” My response was, “That’s not my way of viewing photography, I think it’s more subjective and that there’s more play involved.” We agreed to disagree.

Ahmed eventually invited me to his studio and when I entered I was blown away. Here is someone who is so strict in his vision of photography, and yet his studio is a playground. He has a car on the second floor – I have no idea how he got it up there — images of Donald Duck and verses from the Q’uran hang on the wall: these are all props for his customers to use as elements in their photographs. Four years later, when I returned to Jordan on a Fulbright fellowship, Ahmed and I reconnected and I started interviewing him. I found out he had left Palestine in 1965, that his studio is a replica of his village, Sefferin, that he was unable to return and so the studio became a shrine. Other Sefferinis-in-exile visited the studio to have their pictures taken in front of this “remembered place.” Eventually I also visited Sefferin with his studio as my guide.

Eric Gottesman, ‘Old Thing #4 (Ceramic)’, 2010. Giclee Print from the Studio Karmen series, made in collaboration with Ahmed Taher al-Sefferini.

CMB: There is a great video component to the project, Another Beautiful. A key moment for me is when he says, “Here I feel inside my home, inside the area of my control. It is my true work. No one imposes when or how I should shoot.” In his survival of exile he has created a controlled and contained world in which he feels free. The desire to recover a lost home is also a desire to return to a less complicated time. Perhaps that’s why I was struck by the many photographs of children in Ahmed’s studio. You are also recording what might be the end of his studio – because the shift to digital technology has undermined his business. What becomes of the studio if there are no subjects to activate it?

EG: And what comes of a land if its citizens are not allowed to activate it, especially if another nation is allowed to occupy it? Ariella Azoulay writes about this saying that photography can be a proxy for lost citizenship. In Ahmed’s case, in his own way, he is remotely repopulating a land, Palestine, that he feels very connected to. He had to adapt to life in Jordan 35 years ago and his photographic constructions reveal what was lost. Nowadays, he must also adapt to the shifts in photographic technology. He thinks he may not need his studio anymore and that he might turn it into a hair salon that would make more money. But he hasn’t stopped photographing. Currently, he’s working on a project called 1001 Rocks, where he’s photographing a thousand and one rocks in the desert.

CMB: Your images memorialize Ahmed’s studio. The amazing studio photographer, Seydou Keita, also had a range of props in his studio such as Vespas, phones and European clothing, because his Bamako clients desired to be represented with these objects along with more traditional elements. Your images of Ahmed’s studio highlight the fusion of traditional and modern objects, past and present, self and other. You sometimes draw attention to the places where the illusion doesn’t hold – the electrical tape on a lighting fixture or the traces of footprints on the set paper. What did you want to call attention to by photographing in the manner that you chose?

EG: A number of years ago I read Memory for Forgetfulness, by Mahmoud Darwish. There was an excruciating description of him trying to brew coffee as the bombs fell in Beirut in 1982, buildings crumbling around him. Coffee was his routine, his escape route, his shelter. All this got me thinking of the grand schemes of history and the small elements of a life, how politics and banality intersect. And I am interested in bringing out that possibility through close observation of the instruments of his studio.

I think of Ahmed’s objects as conduits that channel his village in Palestine. His photographic props have a surreal, playful quality to them but they also reveal the nostalgia he feels and his customers want. It is tragic and unjust that he can only relate to his home from a distance, but what he has created at that distance speaks to Ahmed’s creativity, to his personal experience as a displaced Palestinian, to the collective experience of those who must build new homes in new places.

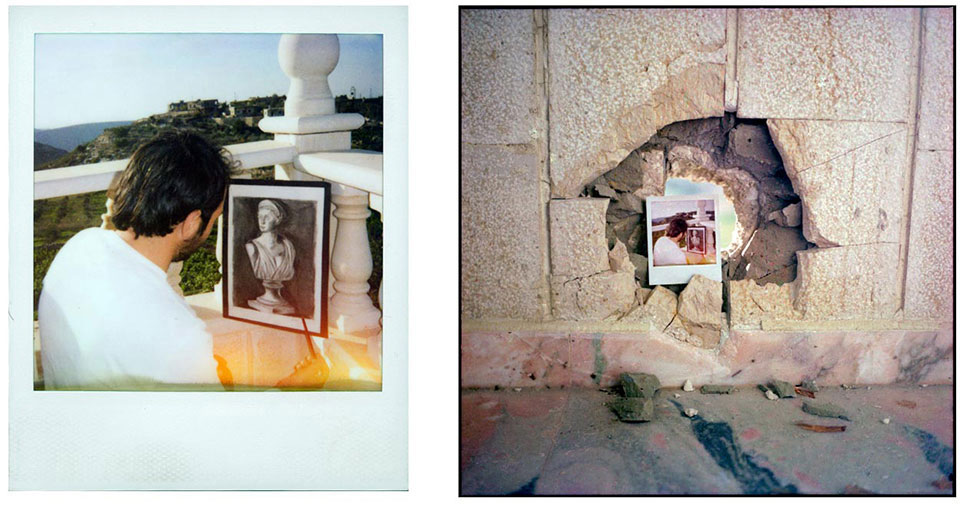

Eric Gottesman, Wassim’s memory before the bombing: “I remember painting a picture.” Reinstallation of Wassim’s memory in damage caused by war, 2007

CMB: Can you talk about how you came to photography and art making?

EG: I was interested in politics in college. Soon after, I received a fellowship to go to Ethiopia for a year. When I first arrived, I was asked to document a drought in the Ogaden desert of eastern Ethiopia for a non-governmental aid organization. My job was to drive with a team of doctors deep into the desert, jump out of our truck, photograph the most desperate people that lived there, return to the truck and continue further into the desert. I designed reports with these pictures and data that led to USAID allocating millions of dollars to assist those affected by drought.

It felt like I was “helping,” but I found the work troubling and the process of reporting inadequate and sometimes disrespectful. I developed deep questions about disaster and “international aid,” ones I am still working out. I remember pointing my camera at a starving mother tending to her starving child, and asking myself: is this the best way to relate to this person? I had a sense that I should be asking complicated questions about the currency of images in that context and in other contexts. I replayed the scene for months afterwards in my mind and thought, “How can I produce a new model to understand social systems and engage in social change?”

Eric Gottesman, ‘Abul Thona Baraka’, 2006. Locally built portable metal structure, weatherproof photographic banners printed locally, laminated gelatin silver and inkjet prints, 2 peer facilitators, coffee ceremony materials. Installed in various towns and villages throughout Ethiopia in collaboration with Sudden Flowers Productions

CMB: A lot of your work involves collaboration. Can you talk about influences and/or role models in terms of collaboration?

EG. Yes, let’s see. People in the communities I have been part of influence me: in San Francisco, in Amman, in Addis Ababa, at Duke, at Bard, in Boston, here at Amherst. I think the person that has most influenced my work is a friend of mine named Yewoinshet Masresha who, over a decade, mobilized women in one neighborhood in Addis Ababa to collectively care for their children. How she did that given the circumstances is a marvel of public engagement.

Here at home in America, I have thought a lot about people who use collaboration as a tool to engage new voices in constructing new histories: Jim Goldberg in Raised by Wolves, Emily Jacir’s early work, David Hammons’ sheep raffle in Senegal, Rick Lowe’s Project Row Houses, Brett Cook-Dizney’s paintings and parties. Theaster Gates is really on point when he talks about this stuff too.

For this project with Ahmed, Susan Meiselas’ Kurdistan, Akram Zataari’s work with Hashem El Madani and studio photography in Ethiopia and other parts of Africa were all major influences in thinking about studio photographs as artifacts from (rather than documents of) an individual/collective history. And I also think a lot about other people building under-the-radar photographic communities in Africa: like Emeka Okerere in Nigeria for instance, Andrea Stultiens in Uganda, Aida Muluneh in Ethiopia. I could go on!

Eric Gottesman, ‘Sudden Flowers History’, 2008. Installation at the Wesleyan University Museum of Art. In collaboration with Sudden Flowers Productions

CMB: Do you consider your collaborations a resistance to traditional photographic methodology?

EG: Collaboration – and by that I mean an inclusion of others into the image- or art-making process – can be a sort of antidote to the venom of colonial projects. The collaborative work I do “resists” a singular way of telling history by filling in what is left out, by offering different perspectives, expanding the canon.

My mentor and now collaborator, Wendy Ewald, sort of invented a form of collaboration in the 1970s that is very much about creating new relationships between photographer and subject, between teacher and student or, as Paolo Freire might have said, between the oppressor and the oppressed. Handing over of a camera from a photographer to a subject —now lots of people do it, but when Wendy started, I believe it was both a subtle and therefore a major act of resistance.

CMB: By giving agency to her subjects, Ewald’s work questioned the fundamentals of the documentary tradition at that time.

EG: Yes, for documentarians, it challenged the notion of perspective; the photographer’s was no longer the only eye that mattered. Wendy’s practice broke down a wall between making stuff and engaging with the world. She put forth an alternative concept of production and display, one that ruptures the myth of the lone artist in the studio isolated from others and from the real world.

One other thing I want to say about “collaboration”; I think there should be more critical discourse in contemporary art about the intentions and results of collaboration, as with [Markus Miessen and Shumon Basar’s book] Did Someone Say Participate? I sometimes wonder whether the word “collaboration” or certain kinds of “relational” work reinforce the very dichotomies of perspective and power that the artist (or architect or cultural programmer) is criticizing. In my own work, collaboration is successful when it peels away the surface and allows me to see from a point of view that is different from my own.

Eric Gottesman and Wendy Ewald in collaboration with the Innu people of Labrador. Water tower installation in Eshku Nitshas Sitenan/We Are Talking About Life and Culture, 2009. Various locations in Sheshatshiu and Goose Bay, Labrador, Canada

CMB: Like you, I use photography to learn to see in a different way. This reminds me of a Virginia Woolf quote that I love, “One can only show how one came to hold whatever opinion one does hold. One can only give one’s audience the chance of drawing their own conclusions as they observe the limitations, the prejudices, the idiosyncrasies of the speaker.” Everyone sees differently so there is an inevitable tension.

Ethiopia must be such a challenging place to produce work. To take images of people who might be considered as deserving compassion can so easily come off as condescending and result in feelings of moral superiority for the viewer. I’m interested in the tactics you use in your practice to communicate with viewers.

EG: You know me, so you can judge whether or not I am personally empathetic, but I have begun to feel that photographic empathy can be dangerous or at least, in the case of my work in Ethiopia, distracting. There is still a lot of photographic history around race and difference to un-do despite many changes in the world and in photographs, and all the critical theory that has been written. People all over the world still see pictures of Ethiopians and want to feel empathy, want to believe, “I can help them!” because that is what previous photographs (and politics, by the way) trained them to see. I try to find a way to defuse that anticipation, to invite those viewers to ask what they are seeing and to surprise them in some way. But I also have other audiences who get a richer reading of my work because they pick up the contextual references and have shed the “empathy reflex” that was drilled into all of us with the photographs of Ethiopians in the 1970s and 1980s.

In my projects I’m often aware of how people have photographed in that place before. Going to other places can be a kind of, as Fazal Sheikh puts it, “trespass.” And in that situation, listening is important for me. As is having the confidence to stay in a place and locate myself within a history of how photographers have done that in the past… and it demands a willingness to imagine that there’s another way of making images.

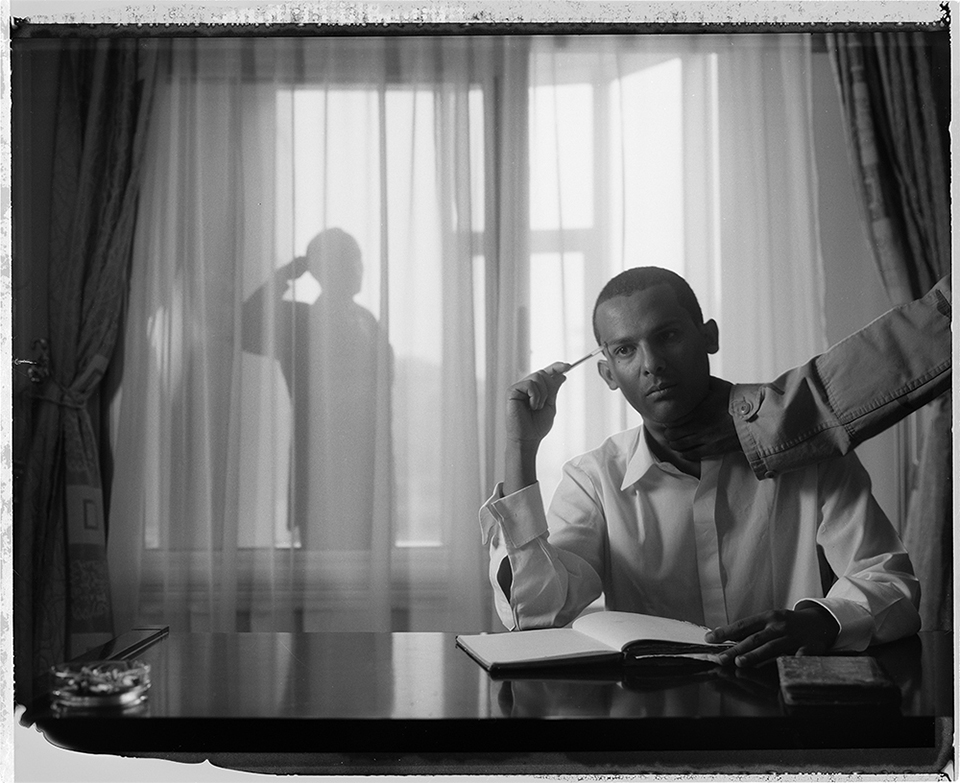

Eric Gottesman, ‘The Last Days of Baalu’, 2012. Digital silver gelatin print from expired Polaroid negative. In collaboration with Daniel Debebe Negatu, Rama Tesfaye, Tegegn Haile and the Baalu Girma Foundation

CMB: Should we go outside and talk about the train project?

EG: Yeah, sure.

[Walking outside along the train tracks in Amherst]

CMB: In 2011, you curated an exhibition in Amman, Jordan inspired by the Hijaz Railway. I was wondering if you could describe work in the exhibition and some of the questions you were addressing.

EG: Well, in my photography project with Ahmed, it was astounding to me that his family’s home was basically an hour away if there were no borders or checkpoints and yet he could not go there. What were these borders about?

In early 2010 my friend Toleen Touq and I started talking about starting a project along the Hijaz, a railway built by Sultan Abdelhamid, leader of the Ottoman Empire, between 1900-1908. It was intended to connect Istanbul to the holy cities of Mecca and Medina by rail. We began thinking about how the region had been one empire during that time and how these lands remain connected despite being broken into different nations. And we started wondering: what remains of that time? Was the railway line itself still there? Did it cross the borders, or was it obliterated in the same way that the empire was? We received a grant from Apexart in New York to research this and our approach was to actually retrace those train tracks.

CMB: How did the Arab Spring influence the conversations you had during the studio visits and the work you chose to show?

EG: The way we found all the work was we traveled from the border of Saudi Arabia in Jordan all the way up to Istanbul along the train line, sometimes taking the train, sometimes by bus or car where the train no longer runs, and we met all kinds of different artists along the way. We ended up with seven or eight artists in the show. Our trip started the day after Ben Ali fell in Tunisia, and ended about a month later the day Hosni Mubarak fell in Egypt.

So the events going on in the region influenced our conversations in every way. We were basically traveling, looking at art, eating and watching Al Jazeera. The demonstrations had a huge impact on me and especially on Toleen who felt a real desire and maybe even a responsibility to be a part of it. In Istanbul, when we realized Egypt was really going to fall, Toleen started researching whether we could get to Alexandria by ferry.

And all this sort of reinforced our initial idea that the borders in the region are artificial and peoples there are connected in ways that are intangible and just under the surface of national identity, and they always have been.

Syrian poet Ayham Agha’s performance at the opening of ‘We Have Woven the Motherlands with Nets of Iron!’, an exhibition curated by Toleen Touq and Eric Gottesman

CMB: Describe some of the pieces and the range of mediums that you included in the show.

EG: We had a number of different artists, most from the region. Asli Cavisoglu, a Turkish artist from Istanbul, made a series of photographs of paintings that she had commissioned based on a film commissioned by the sultan Abdelhamid. That film, which has never been found, recorded the destruction of a building of non-Ottoman architecture. In a nod to the ambition of the sultan’s decision to build the Railway, and in criticism of the hubris and unseen losses of autocracy, Asli’s piece addressed how the Ottoman Empire created its own legacy by erasing others’.

Some of the works addressed how ephemeral borders are, no matter how permanent they seem. Mehmet Fahraci, who works with a collective called A-77, produced an iteration of his piece I Think of You In Arabic But I Love You In Turkish. Belgian-Mexican artist Francis Alys contributed a video he made on an abandoned US army base in Panama that also addressed the absurdity of borders.

We held the exhibition in an abandoned train station in the desert of Jordan; we were interested in staging the exhibition itself along the tracks that we had been exploring – Jordanian artist Anees Maani built a nest-like sculpture from the enormous leftover, rusted iron train tracks in the yard. We were thinking very much about the physical site of the exhibition.

CMB: How many people came out for the opening?

EG: I think about 250 people came to the opening. The trains weren’t running at that point from Amman to Damascus, and so we actually commissioned a train to run from Amman to the site of the exhibition. It was packed. We had to turn people away and add more cars to the train. It was amazing.

CMB: Wow. Who attended?

EG: All different groups, and each car sort of had their own identity. There were conservative suburban families in one car and there was a car of young Western people drinking arak and dancing. Another car of tourists from Japan, and other parts of the world. I think part of it was that the idea of the exhibition, that there is a history to defying the borders that currently divide the region, was extremely relevant at the time. And part of it was the excitement of moving through the landscape of the city in a different way.

CMB: The ride itself was an art piece. This project is such a natural extension of what you’re always doing— facilitating the work of others, connecting people, forming a community around art—creating meaning that way.

EG: Yeah. It was a very public project, a social project that incorporated meeting a lot of people. Through the relationships we created, we found ways of producing something interesting. Plus Toleen and I did most of our curatorial writing over Skype, across borders and thousands of miles, using wi-fi signals to connect to each other instead of train tracks.…I should get a picture of you walking on the train tracks. [Eric takes a picture]

CMB: Where are you headed to after your visiting artist stint ends?

EG: This summer, after I leave here, I have an exhibition with Wendy (that we didn’t even get to talk about) opening at the Addison Gallery of American Art. Also, I received a Magnum Foundation grant to go back to Ethiopia to work on a project centered around a novel written by an Ethiopian writer, Baalu Girma. Girma’s last novel, Oromaye, was published in 1983 and was a thinly veiled criticism of the regime in power in Ethiopia at the time. Five months later, he was assassinated because of his critical novel. I’m working with his family to research his life, translate the novel and make photographs. My friend Yewoinshet Masresha and I just published an English translation of the first chapter last month in Hayden’s Ferry Review; it was one of the first pieces of Amharic literature ever to have been published in English.

Eric Gottesman and Wendy Ewald in collaboration with the Innu people of Labrador, Outdoor installation of ‘Pictures Woke the People Up’ at the Addison Gallery of American Art.

CMB: You are translating literature, too? Your practice is fluid and you don’t allow the medium of photography to define the boundaries of your work. I’ve always admired the rigor with which you approach the exhibitions of your projects. Your exhibitions develop and change according to the context (installation, utilization of local strategies of display, edit of images etc.).

EG: That reminds me of a moment with Ahmed. He is a founder of the Jordanian Photographic Society, a group of photographers that conceive of photography in the same way that he does. He introduced me; kindly describing my work in Arabic at length and I understood small bits of his words about me. I went up to the podium. The packed room applauded, waiting for me to begin to speak as I arranged my slideshow and notes. As he slowly took his seat, he added in English what was intended to be a jab at me but which I took as a great compliment, “Ah yes, one more thing: Eric does not believe there are rules in photography.”