Jeanne Liotta

To hear Jeanne Liotta speak is to be convinced that the formula for an interesting life requires a flexible equation between enthusiasm and skepticism. While her curiosity seems boundless, she is intolerant of both the broad generalizations and opaque language that are often employed to talk about what artists do. She was born, raised and continues to reside in New York City. When not in NYC, she can sometimes be found among groves of aspen trees in the higher altitudes of Colorado where she teaches at UC Boulder. She is also on the faculty of the Bard MFA program. Primarily described as a filmmaker, Liotta is also a multi-media artist working with photography, collage, and live projection performances. Her work was represented in the 2006 Whitney Biennial and has earned numerous awards from the Rotterdam Film Festival, the Jerome Foundation, and the Museum of Contemporary Cinema. Her film Observando El Cielo was named one of the 2007s top films by Artforum and the Village Voice.

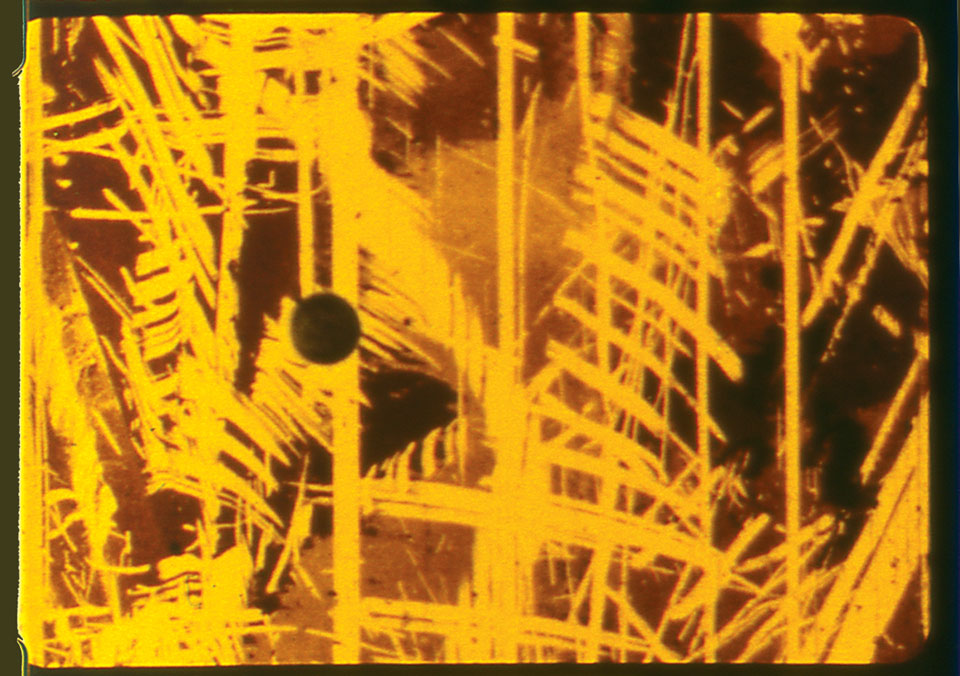

Her film Crosswalk premiered at the 2010 New York Film Festival and has been screened nationally and internationally at venues such as the Ann Arbor Film Festival, the Edinburgh International Film Festival, and the Punta de Vista Festival in Pamplona Spain. Crosswalk is in some ways a departure from the science / astronomy works Liotta has produced over the last decade. It is a collage film culled from footage of several years of religious processions that wind there way through the Lower East Side each year on Good Friday in which a Christ figure drags a wooden cross through the streets while being flogged by young men dressed as Roman soldiers. Traffic lights, police cars, and disinterested passersby occupy the frames as forcefully as the Catholic theatrics. Shot primarily on Super 8 which was then enlarged to a 35mm print, Crosswalk literally and figuratively presents the intersection of time, ritual, geography, and symbol.

Our conversation took place at the Cloister Café in the East Village on a pleasant May afternoon with an Erik Satie remix looping in the background. The topics were wide-ranging, science and art were favorites, but the flow took us to many strange and familiar territories including god, epistemology, and the perfect dessert.

JL – My thing is fragmentary and multiple subjectivities – for me Crosswalk is a collage of time. I read a quote in a biography of Pasolini that Pasolini’s films were like Renaissance paintings in the sense that they collaged historical, mythological, and religious narratives on top of the modern landscape – that he brought these time periods together in one frame. And that knocked me out – I never heard anyone say that about Renaissance paintings. Upon reading that I immediately got on the subway and went up to the Met. It’s not as if I had never looked at those paintings before but I had never considered those things while looking at them. So I am standing there and thinking, ‘Oh, this is Tuscany, there is a tower that was built in 1411 and knocked down in 1612 or whatever, so those painters were looking at their exact surroundings and painting that contemporary landscape and then layered or inserted these old narratives inside of their familiar surroundings. Collaging time – that is what Pasolini was doing – in his films you see these ancient landscapes populated by modern people. And that’s what I thought I was doing with Crosswalk. I am interested in the collage aspect of knowledge, that it is dimensional in time.

MAD – Can you elaborate on that?

JL – I’ve done six retrospective screenings this year in different towns, showing my whole body of work – ‘The Sublime is Now’ a phrase I stole from Barnett Newman and I have been able to review over a decades worth of work involving – scientific-ish subject matter. And there is all this work that is not film or video – photographs, collages, sculptures, handmade books that seldom get seen. But I don’t think of that material as some minor aspect of what I do, that the films are some kind of higher work. it’s all part of the same project…

MAD – But what about Observando Del Cielo, which had gotten so much critical attention, isn’t that piece in some ways a culmination of your ideas?

JL – Well I think of all the material as the ‘science project’ and yes that is the crown jewel maybe but they all go together. So for these retrospective screenings I will show several films and videos including Observando then have a discussion with the audience and then I show Crosswalk at the end because it is a different kind of film. But I could never have made that film, observing in the streets of my own city, had I not made all of this work that preceded it. And being raised a Catholic is not something I talk to everyone about because I don’t want Catholicism to dominate the discussion, but to know the passion of Christ story so well…. But I am a deep believer that knowledge comes from so many different places and we need it all. I don’t have a conventional academic background, so I have learned in my own way, a hodge-podge of sources and influences, to get back to the collage motif.

MAD – One really learns by following one’s curiosities and enthusiasms, and in that sense your approach to knowledge and culture is enthusiastic, it’s obvious in how you talk about things but that quality also in your work. I am also unpedigreed in a certain sense and am led by enthusiasms. One can be self-conscious about that, especially in academic or professional contexts, and there is the danger of dilettante-ism. But to follow one’s enthusiasms and curiosities allows one to be more embracing and less critical, so that collage nature of learning can be very fruitful.

JL – It’s not like the world is a certain way – it’s a construction of many parts and we are participating in that and it makes perfect sense to be in a process of discovery all the time. Also knowledge is not on some progressive trajectory – awareness zigzags all over the place, people forget, cultures forget. Arabic culture had so much wisdom about mathematics and astronomy while the Europeans were digging around in the mud throwing rocks at each other. Discovery is happening all the time and it can be personal. If I discover something for myself – it still feels like an authentic discovery. I remember following instructions in an astronomy book to look up at the Big Dipper and follow a star pattern until you see a faint glow called Sidus Ludoviciana or ‘Ludwig’s Star’. But when I ‘discovered’ that particular star for myself, I dropped my binoculars on the ground from the shock to my system. That I could follow these instructions and see something there and know that I was seeing basically in the same manner as that guy 300 years ago.

MAD – Have you ever had that happen with art?

JL – Yes.

MAD – I ask because your story reminded me of when I saw the Fra Angelico frescoes for the first time in Florence. Each one is painted inside a single small cell where a monk would sleep and pray. The monastery is now a museum of course and you walk down these non-descript hallways but when you bend down to step inside one of the cells you are confronted with this image – the scale is so human, the colors seeped into the wall like dyed skin and I was overwhelmed by the intimate beauty of it, the idea that this image was painted for individual contemplation. Here I was some white trash guy from Boston at the end of the 20th c. shuddering in front of a 600-year-old Italian painting. The mysterious power of recognition across the centuries, shaking me to my core. Is that power in the painting, or is it in me? How does such power get activated?

JL – That image is a tool. It’s not just art, it’s beyond art because its made for use. Like Indian yantras those abstract design patterns, which help in meditation. The word yantra in Sanskrit means ‘machine’, it’s a machine to help you do something. It is ancient knowledge that an image can be a mechanism to help you move, to transform. Speaking of religious paintings I felt like that when I went to see the Isenheim Altar piece by Grunewald. Originally commissioned for a convent where victims of the plague were being tended. So it’s a painting of Jesus who is supposed to have suffered more than any human, yet he goes willingly toward his suffering. So you have to show images to help people endure their own suffering, and its got to be worse than what they are going through. Grunewald’s Jesus is disgusting, he is green, almost melting off the cross, and his mother stands by utterly stricken, white as a sheet. I have never seen anything so abject in religious painting. Originally it was a polyptych so various panels could be opened and closed depending on the message or desired effect, again like a machine with particular functions. On the other side is the painted Resurrection, and equally stunning, the figure of Christ rising through this diaphanous yellow mist. It’s as crazy as a Dali painting. And it struck me that these images are like medicine.

MAD – I am thinking about all those insipid portraits of Christ that hang in middle class American homes in which Christ looks like a 1970s soccer coach or soft rock guy, like Loggins and Messina or a member of the Eagles. That Christ did not need to look like he suffered because pictures like that adorned comfortable homes, so actually looking at his suffering would be ‘icky’ or impolite somehow.

JL – The one I had hanging in my room was the most like ‘Loggins and Messina’ you can imagine, all beiges and browns, the curling hair and soft light…. And you’ll appreciate this, there was a tiny speck of light in his eye and my mother who was a mystical Irish catholic said – ‘See that light? It is in the shape of the Eucharist in the chalice” I will never forget that.

MAD – Did you see it?

JL – I can see it now. And I wondered was it a miracle or was it just something the artist put there, or was it just like people who see Jesus in a tortilla, just a meeting of random shape and projection. But you don’t have to believe it’s true to have the experience.

MAD – Did you study art in college?

JL – No, I went to NYU, studied theater, played in a band, working as a waitress and living in a basement apartment in the east village, everyone lived in basement apartments. I just wanted to be a bohemian, to live a bohemian life. I don’t think I recognized it at the time but that exactly what I was doing. But it was the punk ethos of ‘No Masterpieces’, everyone was doing everything, artists were in bands, the musicians were actors…. it was a super fluid time. We would put on shows, make projections for backdrops, play the music. I worked with a variety of collaborative groups like Gargoyle Mechanique and the Alchemical Theater Company. My art school education started with being an artist’s model, I had a child at a young age and I was wandering around trying to figure out what I was doing or going to do with my life and I started modeling at Cooper Union. That was the first time I ever stepped foot in an art school. And its almost like church, you are sitting there, still. Dealing with duration, listening to artists impart their knowledge. As a model I got so into the art of presentation and the tradition of the artists model I would go home and practice! I’d check out Rodin books from the library and in front of my mirror at home I would try to recreate the poses and gestures in his sculptures and drawings. It was the best job.

MAD – How about film – when did you become involved in film?

JL – I was always into photography, since high school. When I was working with Gargoyle Mechanique I was doing slide backdrops, bleaching and altering the images, thinking about sequencing. Someone bought a Super 8 camera and we used that to make short films. One involved me spinning around in a white dress on a black background. And we did this piece with that film looping through a projector that someone carried through a labyrinth leading the audience to a place where I was actually there spinning. Things like this really got me to thinking about film, performance, structure, and presentation. But I didn’t make my first film until I was 27.

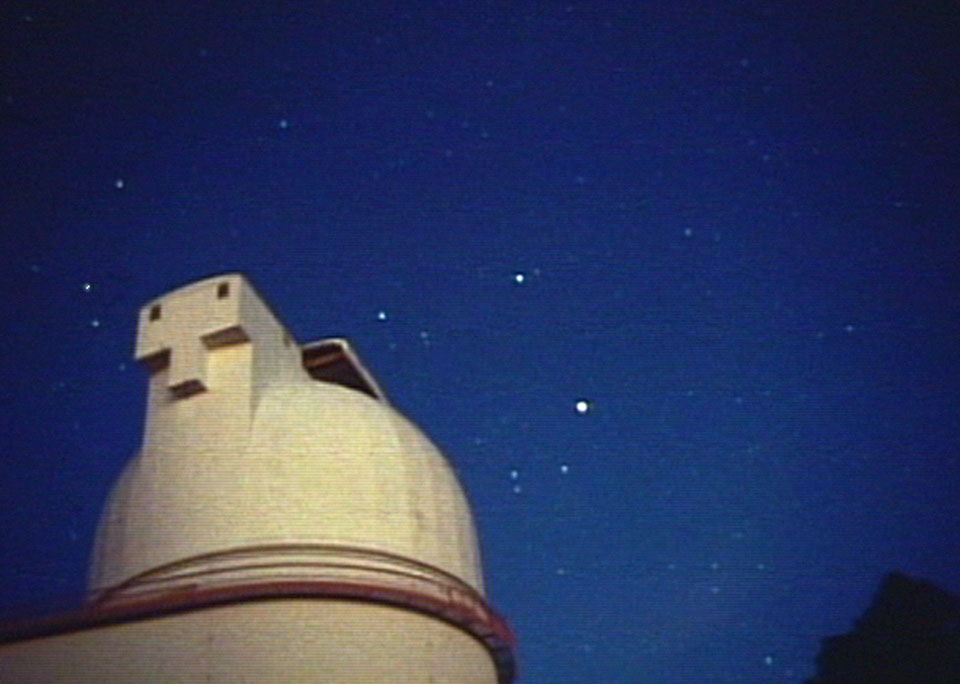

MAD – I wanted to talk to you a little about your film Observando Del Cielo. In talking about this film you described the earth as your tripod. I really like that idea and puts me in the mind of comparing wondrous technologies like the Hubble telescope and the more humble efforts of individual artists – who in some ways are trying to discover and speak about the infinite just with way more limited resources. I generally don’t like the ‘Big Questions’ in art. I prefer specificity, but in your images of the heavens there is a real human quality. There is specificity in the attempt to represent something beyond our comprehension. Your mystery never veers into vagueness or pretense.

JL – I spent 10 years filming and assembling very subjective and fragmentary footage of the skies, and on days I was full of doubt, I would ask myself why I was doing such a foolish and fanciful thing when NASA does it so much better. But that’s our job, not only as artists, but also as humans to gaze up at the stars and contemplate. I don’t like the word ‘wonder’ because it implies an end to itself which seems simplistic, childlike and unconnected to the search for and creation of knowledge. And if you wanted to make images of that you don’t need much – you don’t need the Hubble, all you need is a Bolex, a pinhole camera. But the whole idea of visualization in science is crucial. In a way we are moving beyond seeing faraway objects. We are trying to visualize data and there is an interpretive process there. Scientist’s imaginations and theoretical guesses are at play in imaging the universe, and I love that we are all in this imaginative world together, trying to see what it is.

There is imagery in my film of the starry heavens swirling by just moments of screen time but to capture that footage I had to sit on the side of a mountain for the entire night and I have to say that I had some pretty dark thoughts while I was trying to grasp the enormity of it and it was scary. Insignificance is not the right word, I felt utterly unprotected and joyful simultaneously. Knowing you are unprotected is terrifying and liberating, I wasn’t looking for protection, I was just trying to recognize my being in the middle of all this. I thought to myself ‘This is it, I am alive under the forces’. It ain’t about beauty – it is the sublime, terror, and awe. It’s not like I am against beauty, it is everywhere and can appear at any moment. Ironically, someone once came up to me after a screening of Observando and asked me how could I make such a beautiful thing in such a terrible world.

MAD – Someone asked you that! How rude! Well that should be title of this interview. But really that is so awful and pretentious, and it’s the wrong question.

JL – Yes but it is something to grapple with right?

MAD – I don’t know, That you are ethically suspect because you are not taking on the ‘real’ issues of the world’? Who determines that?

JL – Yes but what my answer was that I was taking on the issues of the world, that is exactly what I thought I was doing. I was really trying to see what is this place that I live in? How does it work? That is initially why I started making that film. Was it possible to make a film like that? We are on these planets spinning in space and it sounds so silly to say it but it’s crazy that that is our reality. We don’t feel it but it can be seen through the Kino eye – the camera helps us see what the eye cannot. I believe in art, I think artists are helping to run the engine of consciousness. So in that sense the Constructivists were right, making art is a kind of labor, an activity that is helping to transform the world. At the very least we get to leave a mark, some evidence of what it was like to live in our time.