Jane D. Marsching

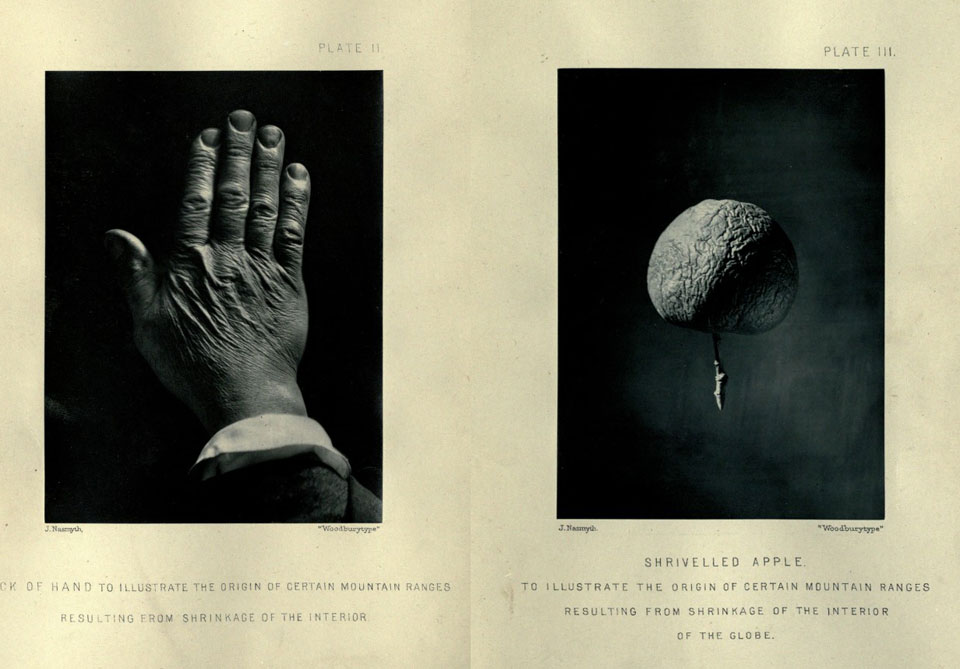

James Nasmyth and James Carpenter, Back of Hand & Shrivelled Apple to illustrate the origin of certain mountain ranges resulting from shrinking of the interior of the globe, The Moon Considered as a Planet, a World, and a Satellite, 1847

These photographs by a nineteenth century Scottish inventor and amateur astronomer flashed up in a college Intro to Photo class. In the darkness through the effervescent dust motes swirling between my body and the vinyl screen, it was merely given as an example in the trajectory of nineteenth century photographs as evidence in science. A brief discussion of early photographic processes, the Woodburytype, which uses a continuous tone with a slight relief. No mention was of Nasmyth’s reasoning: “such maps are pictures of wrinkles,” in an attempt to translate the immediate felt experience of aging skin to distant celestial phenomenon. They did not speak of why we need to translate the abstract into the sensory. That photography can do so, even if much still remains behind the glossy surface. These photographs, in leaping the massive scale shifts of lunar surface and apple peel, in creating formal resemblances from our daily monotonies to a distant satellite of our earth connect our perceiving breathing bodies to scientific inquiry through the fundamental human tendency towards analogical thinking. Analogy groups the discordant and disordered into relationships forged not on harmony, hierarchy, or order, but instead on the chance connections of experience, imagination, and presence. I can still chart the leaps my brain made that fall day: my father’s veins, apple cider donuts, cows in the meadow in my parents home in Woodbury, sunburns blistering, dust motes.