The Ethiopian’s Leg

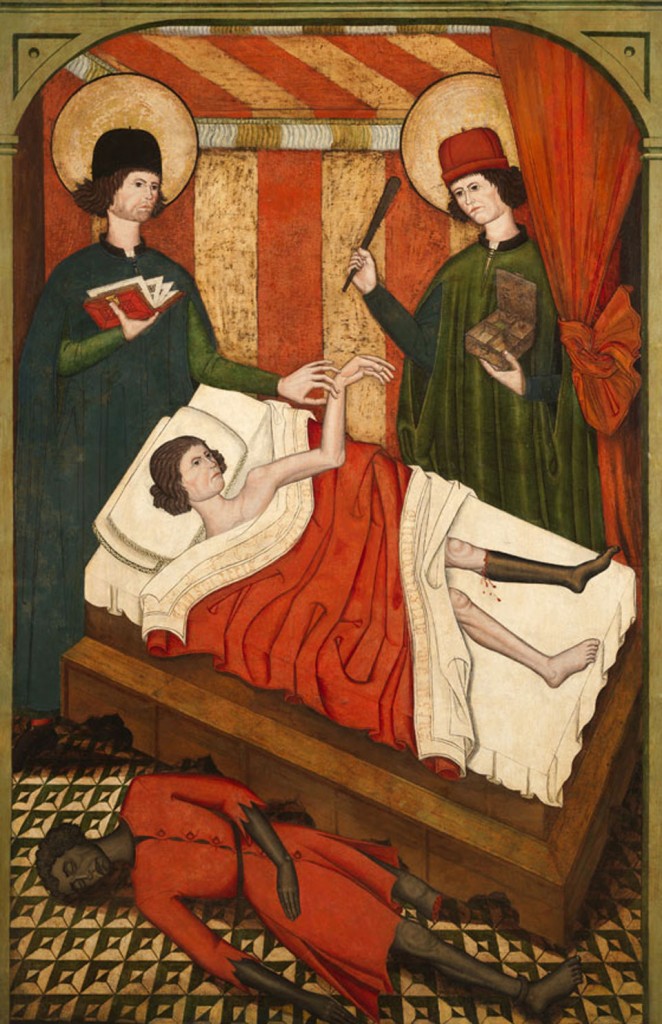

Sts. Cosmas and Damian, ca. 1370–75, Master of the Rinuccini Chapel (Matteo di Pacino) (Italian, active 1350–75), tempera and gold leaf on panel. North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, gift of the Samuel H. Kress Foundation.

There were many things to think about at the Walters Art Museum’s recent exhibition Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe, which chronicled the complex symbolic presence of Africans in European objects and images. But this particular painting held me in its grip.

Saints Cosmas and Damian were 3rd-century twins, physicians and converts to Christianity, who offered their medical services without charge as a part of their Christian duty. One of their most legendary acts was to replace an ulcerous leg of a Roman with a healthy leg from a recently deceased ‘Ethiopian’, or a ‘Moor’ in other versions. The Ethiopian was probably a slave, so the theft of his leg was not considered a desecration, since it was believed that a slave did not possess a soul.

While the biographical record of Cosmas and Damian has been preserved and embellished over the centuries by the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches, nothing, of course, is known of the life of the Ethiopian. Once transplanted will the Ethiopian’s leg become infused with an everlasting soul? Will it accompany the European into eternity? In some renditions the Ethiopian is thrown like a used rag at the foot of the bed. In Fra Angelico’s version only the leg is present, the rest of the body is an unasked question that haunts from outside the frame. In the Rinuccini Chapel painting, the Ethiopian’s body lacks substance, is more absent than corporeal. He is a shadow, a dark mirror to reflect the European imagination.

Here are a few renderings of the Ethiopian’s Leg.

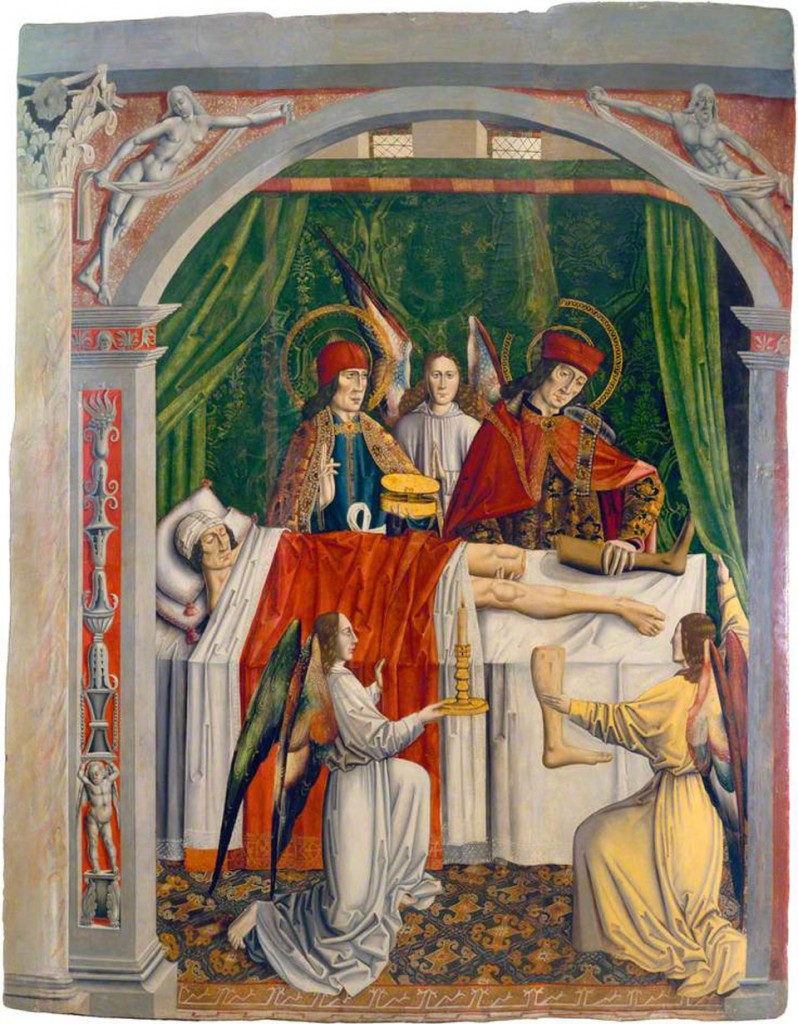

School of Castile and Leon, ‘Saints Cosmas and Damian Healing a Christian with the Leg of a Dead Moor’, 1460-1480

Master of Los Balbases, ‘Saints Cosmas and Damian Performing a Miraculous Cure by Transplantation of a Leg’. c. 1495

Eventually Cosmas and Damian were executed during the Diocletian Persecution. Diocletian came from Croatia. Of lowly birth he climbed the ranks of the Roman army to be crowned emperor in 384 AD. Diocletian was a fervent believer in the Roman Pantheon and saw the growing Christian movement as a threat. He forbade Christians from gathering to worship and attempted to force them to make sacrifices to the Roman gods. Those who refused faced terrible consequences.

Failing to renounce their Christianity, Cosmas and Damian were scourged, crucified and finally beheaded. In this painting, the shields of the Roman soldiers are emblazoned with the heads of Africans, suggesting a symbolic connection between pagan Rome and the supposed animal ferocity of Africa.

Sts. Cosmas and Damian, ca. 1370–75, Master of the Rinuccini Chapel (Matteo di Pacino) (Italian, active 1350–75), tempera and gold leaf on panel. North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, gift of the Samuel H. Kress Foundation.

Mark Alice Durant