Photography and Performance

I will be shot with a rifle at 7:45 P.M. I hope to have some good photos.

-Chris Burden

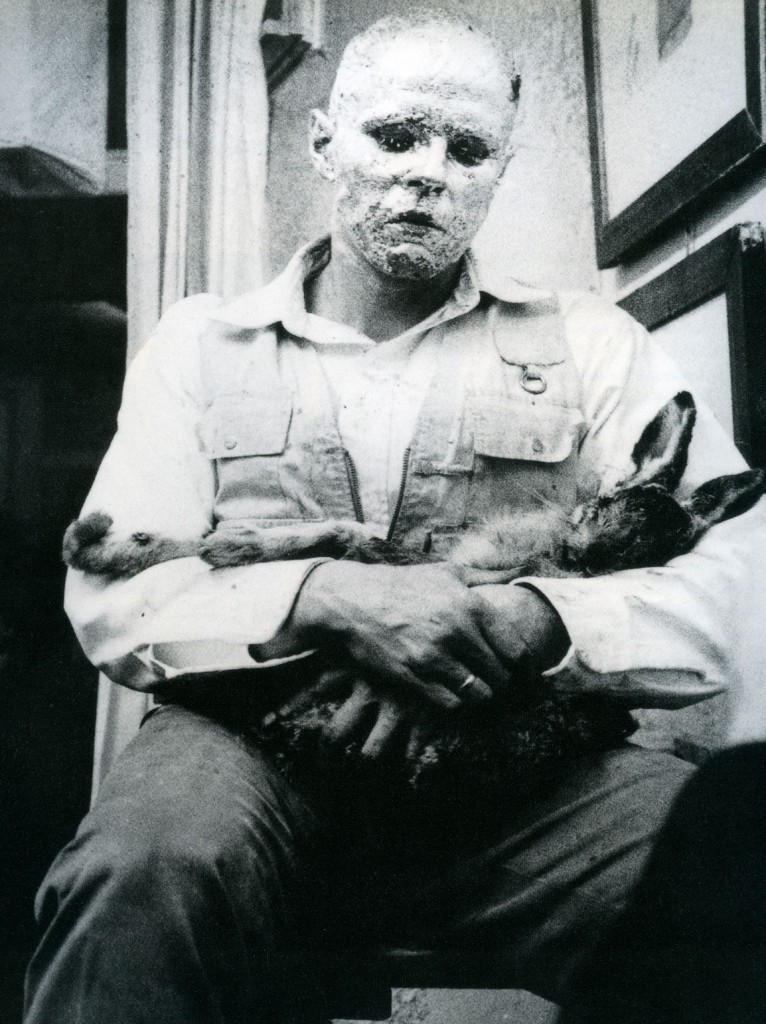

There is something iconic about the images of performance from the 1960s and ’70s. The photographic documentation of fabled Happenings and other actions-by the Fluxus artists, Viennese Actionists, Nouveaux Réalistes, and individuals associated with these groups, either closely or by influence: Joseph Beuys, Chris Burden, Marina Abramovic, Carolee Schneeman, Ana Mendieta, Vito Acconci, Yves Klein, Adrian Piper, and others-may strike us today like rarified chronicles of some lost tribe’s obscure rituals. Wounded arms, conversations with dead rabbits, leaps into the void, self-inflicted bite marks, profane orgies, scrolls unfurling like viscera from the recesses of the body . . . such actions have gained a prolonged life through photographs; they are now burnished in the imaginations of artists, critics, and art historians, to the point that at least some of them seem to be permeated by an unmistakable air of the sacred. Photography serves performance in many ways: by saving the ephemeral instant from disappearance, by composing a moment at its narrative and symbolic zenith, and sometimes by banishing from the frame all that may have distracted the actual witnesses of the event.

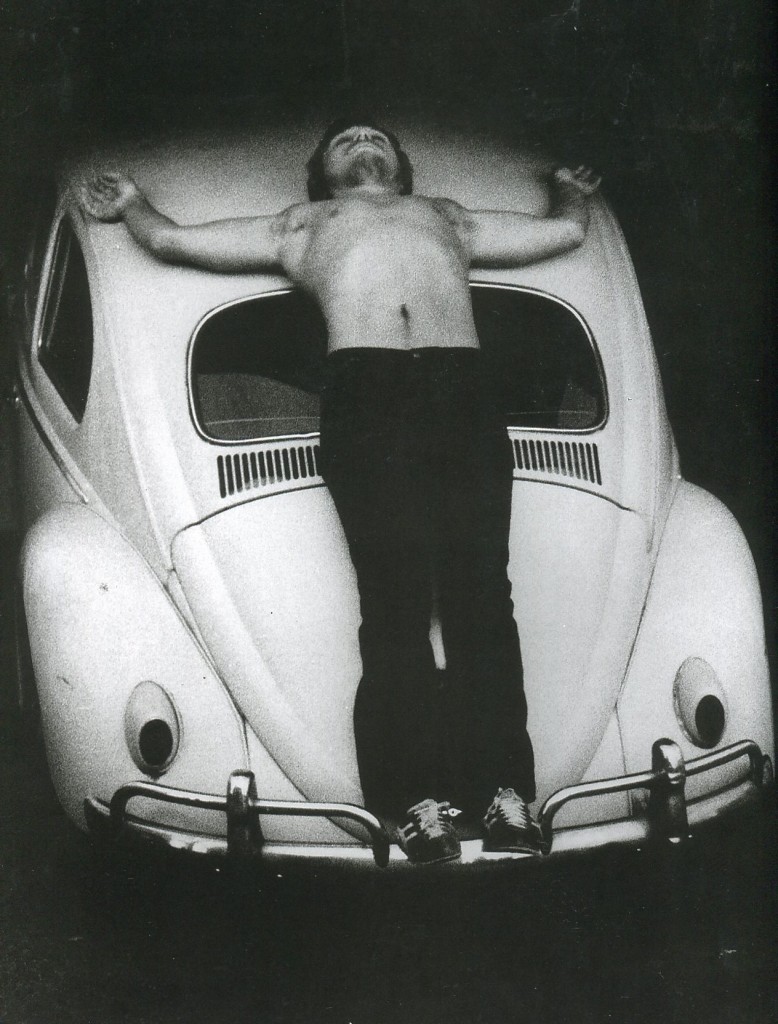

Chris Burden’s 1974 riff on Christian martyrdom, Transfixed, lasted barely two minutes at the Speedway Garage in Venice, California, and was seen by only a handful of people from across the street. The image of the artist’s body splayed over the roof of a Volkswagen bug-to which Burden’s hands had been nailed by an assistant-represents the masochistic excesses of body art of the 1970s and has come to symbolize the violent ethos of its time. Burden’s subsequent ironic presentation of the hand-piercing nails in a glass-and-velvet vitrine, as in a saintly reliquary, has not diminished the legend or the conceit of extreme self-sacrifice in the name of art.

Ana Mendieta’s performances seem to reference pre-Christian iconography. Although the body and the earth were the sites of her actions, she relied on photography to frame and transmit her ideas. We are invited to imagine her actions as they unfolded, but in effect, for most of us today, the photograph is necessarily the prevailing work. Much of Mendieta’s performance imagery is so straightforward and seemingly absolute that we do not envision how or under what conditions they were made: it is as if the image came into existence as an apparition, or a kind of virgin birth. The reality, of course, was less miraculous; just outside the frame of Imagen de Yagul (Image from Yagul; 1973), for example, Mendieta’s fellow graduate students at the University of Iowa were chatting and keeping an eye out for security guards, while her teacher Hans Breder danced around with camera in hand, taking multiple shots. Breder later said of this process: “Ana’s work translates beautifully into photography. The original action was not always riveting, but the process of photographing transformed the work.”

The goal of much performance and Conceptual work of those years was the dematerialization of art: an attempt to separate art from precious materials and pretentious institutions so that it could exist in more pure, less compromised forms. Photography was understood and utilized as a functional medium meant to produce an affectless record, without the taint of style or authorship. That photography was a distinct discipline with its own history and aesthetics was rarely considered; for many, it was seen simply as a means either to document transitory actions or to separate the viewer from direct engagement with an object. It is of course important to distinguish this utilitarian mode from the performance images by photographers such as Peter Moore and Dona Ann McAdams, who well understood the cultural significance of performance art and the necessity to document its events, personalities, and trends-and who did so with rigorous creativity.

As curator Ann Temkin has pointed out, the ongoing power and influence of Marcel Duchamp’s 1917 Fountain is largely transmitted through the images Alfred Stieglitz made of the “original” urinal. Beyond photography’s documentary utility, its ability to distill and embellish the aura of radical process is one reason photographs are essential to the history and posterity of performance. Perhaps the days of groundbreaking body art are in the past, but the documents of that era have been transformed from visual marginalia to images that are every bit as foundational for today’s artists as the canvases of Jackson Pollock and Pablo Picasso were for earlier generations.

So if photography has affected performance, how has performance affected photography?

A performative attitude may be seen in the widely diverse works of Nikki S. Lee, Vik Muniz, Steven Pippin, and Katy Grannan, to name just a few contemporary artists who produce “photographs” as if the word should be framed by quotation marks. That is to say, they embody an attitude toward photography that is informed more by Conceptual art than by the lineage of Great Photographers. In Lee’s case, it is impossible to peel away the performance from its documentation. Whether hers are “good” photographs by conventional standards is more than irrelevant: the very amateurish quality of her pictures is essential to her investigation into establishing identity through the mundane ritual of the snapshot.

The distinction between the documentation of live performance and of actions staged specifically for the camera is often deliberately blurry. Indeed, taxonomy begins to fail us as we seek to peg these works under identifying rubrics: the elaborate tableaux imagery-curator Jennifer Blessing terms it “performed photography”-of Jeff Wall, Gregory Crewdson, Robert and Shana ParkeHarrison, Roger Ballen, and Cindy Sherman, among others, for example. But clearly, these photographers’ works have more in common with both the legacy of fine-art photography and the narrative concerns of theater and cinema, than the visual archive of performance art.

Parallel to the growing ambition and ubiquity of narrative-scenario photography over the last couple of decades has been an incremental (but significant) shift away from the “heroic gesture” in performative imagery toward something more relaxed and playful. Most contemporary artists do not appear to aspire to the mythological status attributed to the founding figures of performance (Matthew Barney is a clear exception here). There is a lighter touch, for example, in the works of Gabriel Orozco, an artist who flits between materials and media like a modern-day trickster. Yet even though the camera has become an indispensable tool in his transformation of the everyday, Orozco has expressed a lack of interest in the conventional concerns of photography. Instead, photography for him is a way to erase the line between the found and the arranged. Cumulatively, Orozco’s seemingly casual imagery offers an inventory of minor delights. These arise not only from the whimsical nature of his “finds,” but also because it is unclear whether the arrangement of objects within the frame is the result of the artist’s intervention or if he just the luckiest and most sharp-eyed flâneur in the world. His shuffling of products in the supermarket, where cat-food cans balance on watermelons, for instance (Cats and Watermelons; 1992), is sweetly hilarious, showing just how easily the categories of the prosaic world can be undermined and reimagined. And the humbly elegant Extension of Reflection (1992), which depicts the transient marks of a bicycle’s tracks through a pair of puddles, is astoundingly economical in its evocation of things both earthly and celestial.

Intrigued by the canonical status that many performance images have attained, and by how these often chaotic and impromptu events had been formalized through photography, Hayley Newman created a faux archive-she calls it an “aspirational portfolio”-for a nonexistent performance career. One action, Crying Glasses (An Aid to Melancholia) (1998), was purportedly created over the course of about a year, during which the artist traveled by public transportation in England and Germany while wearing dark glasses equipped with a pump system to deliver a constant stream of tears trickling down from beneath the lenses. The work was actually photographed (by Newman’s collaborator Casey Orr) over the period of a week, but by utilizing varying cameras and photographic materials, and supplying the work with evidentiary texts in which the dates, locations, and circumstances are fabricated, the artist creates a seemingly larger performance, in the vein of those by Adrian Piper and Bas Jan Ader. Here, the document is unreliable evidence, a masquerade on at least two counts: this is neither a woman truly weeping on the subway nor is it a record of an authentic yearlong performance. Remarkably, despite its deceits, the image remains affecting, evoking both compassion and wry acknowledgment of the power of photographs to compel in spite of their artificiality.

Melanie Manchot explores the boundaries of trust and intimacy in a range of works in performance, photography, and video. Gestures of Demarcation (2001) is a series of six photographs in which a naked Manchot faces the camera in a variety of urban and rural environments, while an androgynous figure, facing away from the camera, tugs at the artist’s naked skin. Like a contemporary Saint Sebastian, Manchot seems unaffected by the repeated violation. Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece comes to mind (a Happening first enacted in 1964, in which audience members were asked to join the artist onstage and cut away at her clothing), as do several of Marina Abramovic’s performances, in which viewers were invited to interact and even violate the artist’s body with an assortment of implements. By contrast, with Manchot’s works, although we may experience a visceral reaction to the intrusion, the event is enacted solely for the camera and not for a live audience: the viewer is thus never personally implicated in the breach of the artist’s physical boundaries.

To paraphrase Maurice Merleau-Ponty, the body does not occupy space like an object or thing, but instead inhabits, animates, or even haunts space. In Erwin Wurm’s “one-minute sculptures,” the body performs or experiences a slapstick rebuke of personal space and social etiquette. Wurm cloaks his Conceptualism behind the deadpan nature of the snapshot in pictures such as Looking for a Bomb (2003), in which a kneeling man reaches deep into another man’s pants; Inspection (2002), in which a woman sits with a friend in a restaurant while stoically enduring a man’s head thrust deep into her blouse; and the self-explanatory Spit in Someone’s Soup (2003). These rude interventions in the everyday are part of Wurm’s larger project Instructions on How to Be Politically Incorrect.

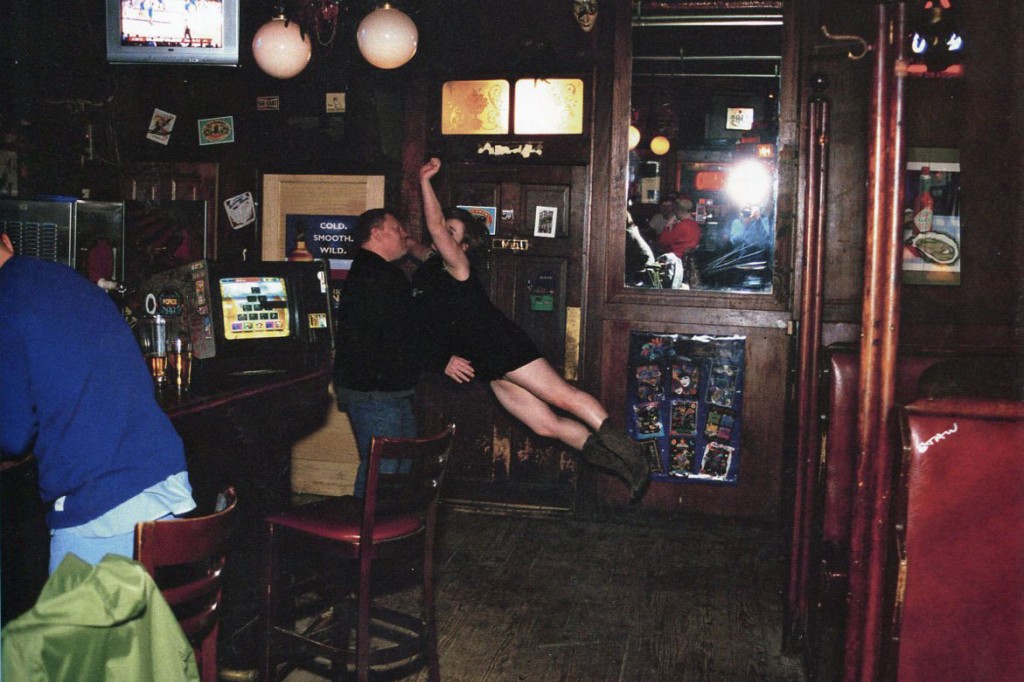

If all we saw of Lilly McElroy’s work were a single photograph of a young woman frozen in midflight, we might construe it as simply an embarrassing moment of drunken excess. But the cumulative effect of her series I Throw Myself at Men (2006-8) transforms an indecorous act into a playful riff on late-night desperation. McElroy describes the series as “loving and cruel . . . literal and clumsy, a cross between physical comedy and earnest confessional.” That’s a fair assessment of these deliberately awkward moments in which the artist/protagonist flings herself toward apparently unprepared male subjects. Like Girls Gone Wild meets Yves Klein’s Leap into the Void (1960), I Throw Myself at Men combines low-rent barroom behavior with a performance artist’s bravado. The cheap spectacle is made all the more pathetic by the pedestrian style of the photographs, in which the flash fills and flattens every reckless action and grimy barstool.

William Lamson is unique among this group in that he was an accomplished photographer who produced finely composed portraits and landscapes in the social-humanist tradition before deciding to spend more time in front of the camera than behind it. Crediting Roman Signer’s “action sculptures” as a catalyst, Lamson now works in sculpture, video, and performance, as well as photography. His performance-inspired photo-series Intervention (2007-8) could be described as documents of temporary urban earthworks. As if to convince us that the world is full of these lesser epiphanies if we would only open our eyes to see them, Lamson’s simple and direct photographs allow us to imagine stumbling upon random poetic collisions of materials, such as a helium-filled balloon strategically placed to blind a surveillance camera; a ladder made of twine and bananas, scaling a tree; a discarded mattress pinched into a bald tire like an elderly man squeezing into his old military uniform.

Joseph Beuys is said to have consciously drained his performances and installations of color in order to distance his work from real life, desaturating his actions to make them more like black-and-white photographs. Beuys understood the photographic document not simply as a necessary footnote to the main event; rather, the image had the talismanic authority to transmit his disembodied power through time. Nonetheless, viewing the iconographic record of 1960s and ’70s performance art, you get a sneaking sense that if you were not there, you were sinfully absent from a hallowed event-you missed Jesus walking on water because you were too young, not hip enough, lived in the wrong town, or were just too lazy to go out that evening.

It is a paradox that photography and performance, tied as they are to the transitory, fused to create such an august archive of dramatic images. The utopian themes that were circulating in the 1960s and ’70s were often embodied in the redemptive gestures of performance art. The shine may have faded on the messianic promise of image and action-but in fact it may be healthy not to indulge such romantic fantasies anymore. Mia Fineman writes of Orozco’s photographs: “At times, it seems like he is simply adding punctuation to the prose of the everyday.” This notion articulates the more earthbound ethos that marks our diminished expectations of art and life.

Some of Melanie Banajo’s photographs, for example, reveal an attitude that finds temporary solace in the humor of dispirited futility. With echoes of Charles Ray and Martha Rossler, Bonajo’s Furniture Bondage series (2007-8) presents an array of anonymous young women, trussed to the saddest assortment of generic domestic items. Unencumbered by any duty to the heroic, yet still capable of provocation, Bonajo’s photographs present a cruel joke, as if Ikea had promised salvation but delivered only unrelenting boredom. We laugh, and then an uncomfortable shudder of recognition chills our bones.

Originally Published in Aperture No. 199, Summer 2010