Paul Chan

Paul Chan, detail from Happiness (Finally) After 35,000 Years of Civilization, courtesy of the artist and Greene Naftali Gallery.

I met Paul Chan in 1999 when I began teaching at the Milton Avery Graduate School for the Arts at Bard College. I know this sounds like hyperbole but when I walked into his studio for the first time, I felt like I was stepping into the future of art. Not in any weird messianic way, just in the complex, subtle, inventive and accessible manner that his work was mapping its own territory. There was something about his unrelenting focus, his generosity that manifested in his articulate embrace of ideas from all over the cultural spectrum and his ability to laugh easily at everything, including himself (For example, if you click on the ‘complete profile’ link on his website National Philistine, you are taken to the obituary for a doctor who shared his name). But most of all, Paul’s work gave me shivers.

He achieved almost instant recognition when he exhibited Happiness (Finally) After 35,000 Years of Civilization in 2002. Happiness…. is an 18 minute animated loop projected on a floating screen shaped and textured like a torn scroll. Since then, Chan has exhibited his work at the Venice Biennale, the Whitney Biennial, Documenta, The Serpentine Gallery, the Museum of Modern Art and the New Museum. In 2007, Chan collaborated with the Classical Theater of Harlem and Creative Time to produce a site-specific outdoor presentation of Samuel Beckett’s play Waiting for Godot in New Orleans. In 2010, Chan founded Badlands Unlimited, a press devoted to publishing artist writings and writings about art in both paper and digital forms.

This conversation took place at Chan’s Brooklyn Navy yard studio on January 14, 2014.

MAD: When you were in the grad program at Bard, you were already working on Happiness…, in fact you worked on it your entire time there.

PC: That’s right

MAD: Was it difficult to work on such a long-term project in a grad program when there is pressure to resolve things, to move on and be productive? Did you know it was going to be such a consuming project when you started it?

PC: I didn’t expect anything out of it. I just needed something to hold my attention. I was doing other things while I was in grad school, but Happiness… was the one that held my attention the most, so I kept doing it. The form changed over time, through exposure and conversations with others in the program.

MAD: What was the starting point for Happiness…? Was it a particular image or idea?

PC: It was a question. What is Henry Darger? I went to school in Chicago at the School of the Art Institute and at that time during the mid 1990s, outsider art was in the air. I was exposed to Darger, Bill Traylor, and Howard Finster. Lee Godie used to sell her work on the steps outside of the Art Institute. I was in the film / video program and intellectually it was so far away from the outsider art I was drawn to. Maybe it was attractive precisely because it was so far away from what I was doing at the time. I couldn’t make sense of him or his work. The more I looked at the work the more I asked ‘What is going on here?’ I didn’t know what I was looking at and that was the beginning.

Paul Chan, detail from Happiness (Finally) After 35,000 Years of Civilization, courtesy of the artist and Greene Naftali Gallery.

MAD: That reminds me of something you said a year or two ago in a talk in Hong Kong that the power of art, for you is when you cannot make sense of something, when it is outside the realm of what you know. There is something about Henry Darger’s work that is beyond some level of comprehension. The Vivian Girls for example, who are in Darger’s work of course, and in Happiness…, they are forever young, hermaphroditic, exuberant and perverse, loving and fierce. They are so familiar, partly because Darger traced from commercial images as a source of his pictures, but their behavior is so other, so unexpected in terms of human interaction.

PC: Strangeness and attraction, flipsides of the same coin. As I hear you describe the Vivian Girls it make me think that those are all the things that we wish we could be. They embody the plenipotentiary. Darger imagined them having all the potential a human being ought to possess in order to be fully human. And that is very compelling and perverse. This also why Charles Fourier came into the picture. Fourier became the prism through which I began to understand Henry Darger. Fourier was not a perverse outsider artist but a political philosopher and for me Darger’s world is a manifestation of what Fourier wrote about. Fourier enlarged the notion of self to encompass not only political and social aspirations but sensuous ones as well. Fourier is the only philosopher I am aware of who philosophizes using desserts as metaphors. He spoke endlessly about tarts and pies. Why would a philosopher use tarts as a metaphor for thinking about political and social progress? It makes perfect sense if you are trying to enlarge the self as an emblem of society.

MAD: Another compelling thing is that this utopia envisioned by Darger, Fourier and yourself is not all sanitized, maddeningly altruistic and ultimately boring, like some Christian vision of heaven or communistic paradise of egalitarianism, there is room for darker, more idiosyncratic manifestations of happiness. I think surprise is really important.

PC: This is true; it’s part of the pleasure of life and maybe one of the few pleasures of art. On the other hand, I want to speak up for those sanitized and boring utopias. Plato’s Republic may be one of the boring utopias. But I respect it insofar as I understand Plato’s history. Particular life experiences shaped how he wrote it. Now, I don’t want to reduce everything to biography, but life experiences matter. The fact that he was betrayed and enslaved by a tyrant before he wrote the Republic says a lot about what he thought we needed to know so we don’t end up in the same situation as he. I imagine the rigidity of something like the Republic speaks to a kind of philosophical vigilance Plato felt was essential to what he was writing against.

Paul Chan, detail from Happiness (Finally) After 35,000 Years of Civilization, courtesy of the artist and Greene Naftali Gallery.

MAD: You have probably been asked this too many times but you were working on Happiness… when September 11 happened. I could be wrong but I remember that Happiness… already had catastrophe in it before 9/11, is that true?

PC: It is.

MAD: So what happened? Did it change your attitude toward what you thought you were doing with that piece?

PC: I literally changed the piece. I made it more extreme, more sex, more violence, more of everything.

MAD: There is a sequence toward the end of Happiness… Before it loops back to the beginning, that shows an old cemetery as gravestones, plinths, broken monuments, and cenotaphs rise in the air. It is such an unforgettable image, and in later works you also image objects and bodies falling and rising into the sky. I am reminded of a story that Maya Deren told about a short sequence in her first film Meshes of the Afternoon, in which she moves across the room from the dining table to the chair where her sleeping self is resting. We see a quick 5 or 6 shot sequence of her foot moving through varied landscapes, a field, a beach, a sidewalk, a carpeted floor. She said that when she saw this sequence projected, she saw the future of her work, that quick succession of images traversing these topographies opened her eyes to how succinctly film could shape the relationship between time, motion and space. And I am wondering if that sequence in Happiness… had a similar resonance for you in terms of your future work?

PC: I think the echoes of the floating reverberate in what I have done after Happiness… but I would say it is less what was in the work and more how I made it. It was the first long-term project that I did when I felt like the time wasn’t wasted. I made Happiness… because I needed to pay attention to something worth paying attention to. And I discovered that in order for me to find pleasure in the attentiveness I had to do it over a long time. It took around three years.

Godot in New Orleans, for example, didn’t take as long as Happiness… but it took two years and I was all in, especially when I moved to New Orleans. So it’s not about the particulars of the work but about the time spent. The commonality between the works is that it takes a long time to get to that place where I can really pay attention to what it is I am doing.

Or Badlands, which I started in 2010. I knew it would take 5 to 10 years for it to be something. We are four years into it and I feel like I am just beginning to understand what it is we are doing, but in the process I have given myself the space to be attentive to it. It’s a luxury to be able to give yourself that time and space.

MAD: That’s the bubble we can create for ourselves when we are totally devoted to a task, it’s not literally outside of time but our experience of time is so different from our conventional experience of time.

PC: It’s as close to eternity we get: the perpetual present.

MAD: Last question about Happiness…, Really. The same summer we met, in 1999, two films, Kubrick’s last Eyes Wide Shut and South Park the Movie, were released. I saw them both at the Red Hook Theater and I had a kind of epiphany….

PC: That Happiness... was the bastard child of Kubrick and South Park (Laughter)

MAD: Well, maybe something like that. I realized that the ‘auteur’ moment had passed. I mean, growing up, I had been a devotee of Kubrick and any number of other auteurs of the cinema, Truffaut, Goddard, Fassbinder, Wertmuller, Herzog, Bertolucci. Eyes Wide Shut seemed so clunky, so strenuous in its attempt at depth. But South Park, with its inexhaustible rapid-fire sarcasm and rudimentary animation, got to complex and provocative issues with such economy. I thought that there was something about animation that offered surprisingly, although maybe not for you, a way forward.

Paul Chan, detail from My Birds……trash…..the future, courtesy of the artist and Greene Naftali Gallery.

Paul Chan, detail from My Birds……trash…..the future, courtesy of the artist and Greene Naftali Gallery.

PC: It was a way forward. One of the frameworks for making Happiness… was banner ads. Early on the web, what was most exciting for me was all the banner ads. I think what was powerful about South Park when you saw it was that a form that had no esthetic or intellectual ambition was raised. The impoverishment of that animation was raised beyond what was expected. At one point with Happiness…, I thought I was making an 18-minute banner ad. When I started Badlands people hated e-books and asked me why I would waste my time doing that. And to me that’s exactly what I should be doing precisely because of that attitude, no one expects anything from an e-book, at least nothing good.

A similar thing happened with Godot, across the board people tried to talk me out of going there and doing the project, for all sorts of reasons. I wasn’t from New Orleans; I wasn’t black, or white, for that matter. I don’t know the culture or politics of New Orleans, I am not a Beckett scholar, I am not a theater person, the objections were legion. But I am the kind of person that when I hear things like that I think I am on the right track.

MAD: It’s not so much about being contrarian necessarily, right? I think when people react to things that way what one is often encountering is a boundary. Some limit of what is acceptable or permissible. Boundaries need to be examined and tested if for no other reason than to determine whether they are useful, necessary or even harmful or limiting. Pay attention to your resistance I always tell my students.

PC: And for someone like me going toward that resistance is pleasurable.

MAD: Sometimes your work takes on history with a small ‘h’ or a capital ‘H’. I think of the relationship between Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo. I mean, they were as intimate, I suppose, as a couple can get. Married twice, had very similar politics, and circle of friends. But their approach to representing history was very different. For Diego it was always history with a capital H – the big canvas, the epic sweep, cast of thousands. For Frida it was ‘history happens here, to this body’, even the scale of her images is intimate, personal. I like the way your work goes back and forth from the particular such as Baghdad in No Particular Order or the video you made of the American political prisoner Lynne Stewart to the meta-narratives like Happiness… or My Birds…. trash….. the future, or even the 7 Lights.

PC: This is just common sense to me, we understand history, whatever that may be, through the very practical presence of people. And when you say little ‘h’, what I hear is ‘people’. We don’t understand history unless it’s sedimented in people. T.S. Eliot said ‘A lifetime burns in every moment’. We are time capsules whether we like it or not. And in my experience I’ve understood politics insofar as it relates to living people. So the Lynne Stewart piece is about her but she is not just her, insofar as a self is only oneself when it is enlarged in some way. And she certainly enlarged herself through her political work and experiences as a lawyer. Our ability to be sensitive to the time capsule quality of people is what gives us the potential of seeing them anew. Or perhaps just seeing them at all.

MAD: In your essay for The 7 Lights catalog you observe that despite a 110-year history, film is still essentially experienced as a window. Photography has similar limitations in that no matter how one tries to disrupt the image, there is always this unshakable anchor in time. In Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes makes a distinction between film and photography by stating that because film can never be ‘still’, it can never be pensive or contemplative because the image is always being replaced by the next image.

I wanted to ask you about the loop, the film loop, which you use often in your work and I know you have addressed in in some of your writing. It’s an interesting device for many reasons, including that it undermines narrative closure. But relevant to this discussion, it seems that potentially the loop can create a contemplative environment.

PC: I agree but to me contemplation is not still but rhythmic. The time of attention that we were just talking about doesn’t feel still to me, it’s rhythmic. That’s why I might listen to one song over and over again in the studio while I’m working, it could be for 16 hours but I don’t experience it as repetition, but rhythm. The loop to me is the most generic form by which that rhythm appears. So I don’t think of Happiness… as an 18-minute loop but as a rhythm that has peaks and valleys, it just goes. It creates enough oscillation so I can experience time. I think all of my moving image pieces tend to work that way.

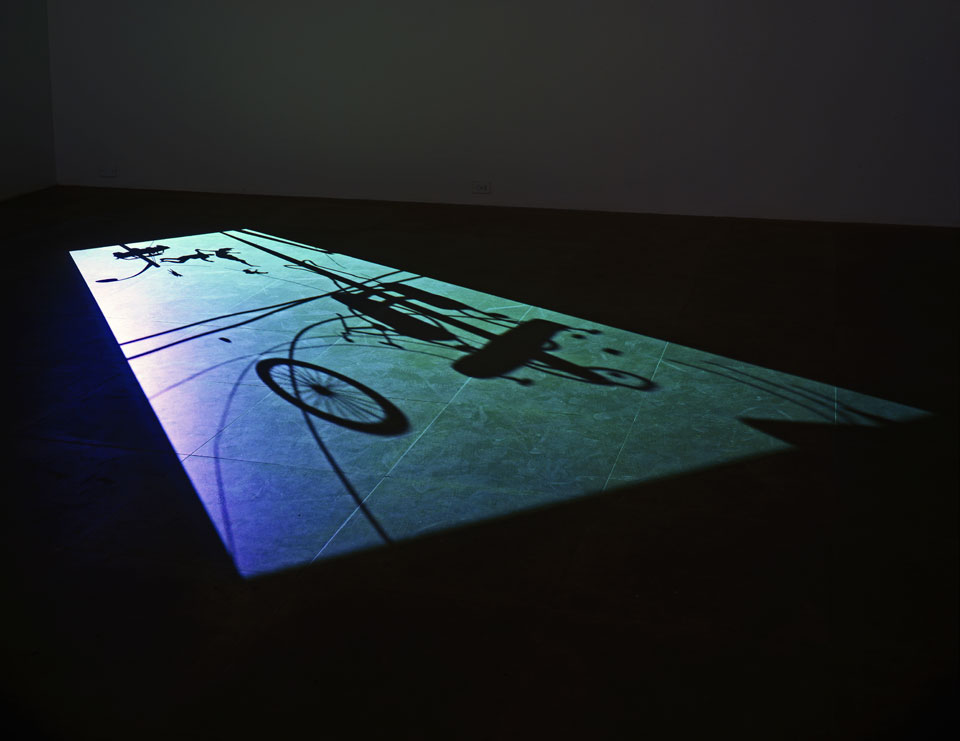

MAD: In the 7 Lights you taken the texture and most of the color out and reduced representation to silhouettes. That reduction might be problematic in the sense that the work could be read as a semiotic play of signs emptied of their specificity. But what is so magical about 7 Lights is that despite this reduction there is a deep feeling of individuality. For example, a silhouette of a cell phone or a body floats upward as seen through a window frame, and instead of referring to some generic cell phone or person, I don’t know how you achieved this but I am struck by how utterly specific they are and therefore all the more emotionally communicative.

PC: Right, it’s not ‘a’ cell phone, but ‘that’ cell phone. The supernatural is the natural precisely rendered, right? And I was certainly thinking about that when I was making the 7 Lights. I realized that that cell phone floating up had to be a Motorola Razor and it had to flip open at a certain speed for it to feel like it’s popping open. I like to think that level of attentiveness manifests itself in the form and whether or not you know the difference you feel the attentiveness embedded in the form.

Paul Chan, detail from Waiting for Godot, New Orleans (Robert Lynn Green Sr.), courtesy of the artist and Greene Naftali Gallery.

Paul Chan, detail from Waiting for Godot, New Orleans (J. Kyle Manzay and Wendell Pierce), courtesy of the artist and Greene Naftali Gallery.

MAD: While I did not see Waiting for Godot in New Orleans, I did see the sets and ephemera installed at the Museum of Modern Art. Instead of artfully or well-crafted objects you used generic Home Depot materials such as blue tarps, foam core, twine, and again, these materials seem to generate an intensity that belies their humbleness. Did you help install that piece at MoMA?

PC: I planned every square inch of it.

MAD: I recently saw a show of Chris Marker’s photographs at MIT and I was thinking about you in relation to Marker. Your works are not similar in any stylistic way but there are some resonances there. First of all, La Jetee is unique in the history of cinema, one would think others would try to copy it, especially because it is so technically simple, but it resists because despite its apparent simplicity it is too idiosyncratic. Happiness…… is like that too; it has a strange, hypnotic, power, despite its superficial simplicity, like the rudimentary animation. There are thematic parallels as well, the catastrophe, the feeling of being loosed in history, and although La Jetee is a narrative, it has its own loop-like quality. Both La Jetee and Happiness… are unapproachable, I don’t mean inaccessible, I mean they resist imitation.

PC: I wanted it to be unapproachable. From the way I installed it, high in the room, to the small scale and low resolution of the figures. As perverse and pleasurable as I hope it is, there is a Platonic quality about it. Your inability to get close to it was my way of acknowledging that no matter powerful and potent we might think Darger’s work is, he was still a particular man and perhaps a particularly tragic man who tried to transform whatever it was he was going through into these forms that we are still baffled by today. He essentially made an escape plan for one. I don’t know if Happiness... resists imitation. What I do know is that my particular need to be attentive shaped how I made it. And the more particular and individuated the need is, the more singular the making becomes. I have tried to escape this world as much as possible through frameworks of attentiveness. This may be the most generically political aspect about me. I know this is the world we have and that we are not going anywhere. Heidegger was wrong: no god is going to save us. We are on our own, we have been marooned here. So what are we going to do?

MAD: One has to make a choice, I think much of great art provokes that feeling for me, I’m not sure I ever do actually make a choice, but in that moment of communion I feel like I am choosing to go with the transformative power that art can embody.

PC: To take up the cause of what it means to be creative or cunning, which is to give yourself a choice where there are none given. I think there is very little separating the notions of creativity and cunning. The works that I pay attention to are the ones that remind me of that. Chris Marker for instance. When I first saw his stuff, I never knew you could combine history, moving images, critique, poetry, sex, eroticism and old fashion hardcore political thinking. I never realized it was possible to do that until he did and I saw it. I am baffled to this day.

MAD: You proposed something like this in a talk / debate in Hong Kong last year. The debate used the language of the Occupy Movement; I think the issue was whether contemporary art excluded the 99%. There were two people speaking to each side of the debate including Joseph Kosuth. You did something that was rather cunning, you didn’t avoid the issue so much as to reframe it by making the extraordinary claim that great art excluded 100% of the people. By this you sidestepped the simplistic binary of exclusion and exclusion and instead pointed to the impoverishment of our imaginations. Your point was that great art enlarges our sense of the possible so that we find it harder to accept the world we are living in.

PC: Within the framework of that debate and with what we live with here in New York, what constitutes contemporary art tends not to be about those transformative experiences, but rather about the openings, collections, auctions; contemporary art as a cipher for what constitutes the good life. But we know in the history of philosophy that there are many claims for what the good life is and perhaps the political work is to make other claims. To simply accept the proposition, as it exists that contemporary art is a cipher of the good life as expressed in luxury and material wealth is short sighted. It may be true. But it’s not the truth.

Paul Chan, detail from Happiness (Finally) After 35,000 Years of Civilization, courtesy of the artist and Greene Naftali Gallery.