Nayland Blake

As an artist, writer and teacher, Nayland Blake has been a significant figure in the art world for three decades. Variously described as funny, tender, brutal, spare, cerebral and visceral, his work in sculpture, performance, installation and mixed-media explores ideas of power, identity, sexuality, philosophy and popular culture.

Represented by Matthew Marks Gallery since 1993, he has had major exhibitions at the Whitney and Venice Biennials, the Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College and more recently at the Yerba Buena Arts Center in San Francisco presented his solo exhibition Free!Love!Tool!Box! in 2012. Nayland is the Chair of the International Center for Photography / Bard MFA program.

This interview took place in his ICP office on November 1, 2013.

MAD: I was preparing some of these questions on the bus – I can barely read my own handwriting.

NB: Why yes I have always considered myself a baloney. (Laughter) That is an excellent question.

MAD: That ties into your work in so many ways. (Laughter)

MAD: On your website I watched a lecture you gave at CCA in which you tell the audience consisting primarily of students that they needed to create the art world that they wanted to live in. Also I have heard you use a motto of sorts ‘Make Art, Make Change’ and I am wondering if that’s the change you are talking about, changing the art world, or is it bigger than that?

NB: When you take on the process of consciously creating than it can provide the vehicle for anything else. By thinking through questions like ‘How do people encounter the things you make? How are they shared, what is the communication around them?’ Things that are structural art world issues, issues that the art world as we understand it, has been designed to solve, once you start to question the usefulness of those solutions then it bleeds over into other areas of your life. I guess that I am a classic liberal in that I imagine that self-knowledge and self-awareness make people better citizens. Art is the path that I have found for that kind of self-exploration and self-understanding.

MAD: And in creating the world you want to live in internally and externally.

NB: I do believe that we are always doing that. That if you narrate the world in a paranoid way, that’s the world you live in. That you create a world in which people conspire and you don’t have any power……

MAD: I’ve got to work on that one myself……(Laughter)

NB: We all do. Those are stories that are available to us, not ‘truths’ that we discover. You have to ask yourself the question, ‘Why is that story comforting or persuasive to me?’ I heard something today on a podcast that really resonated with me. Someone was talking about current movies that are marketed toward kids, animated movies that seem to always imply that ‘If you believe hard enough you can do anything’ and they were linking it to thinks like American Idol, that in the cult of self-esteem we’ve encouraged people to think that they don’t have to make structural change. If they want success they just have to wish hard. And that is not true. (Laughter)

MAD: And it implies that one has to ignore everything and everyone else that one has to take care of one’s own dream, to the exclusion of making societal change.

NB: For me the two big lessons in my life came from Punk, in its New York, art version and the AIDS crisis. Which were both situations where the systems that were in place were not adequate or did not provide reward and validation or even worked actively against the people engaged in them. Structural change had to be made by people who were not experts.

MAD: Let me ask another broad question. You grew up in New York, went to grad school in LA at Cal Arts and then you moved to San Francisco. Can you talk about how location and institutions influenced you and your work?

NB: I moved to San Francisco because everyone I knew who was young, hungry and career oriented from Cal Arts, was either staying in LA or moving to New York. I knew what New York was like and realized that I needed some time to be in a place where I could find what my work was. San Francisco seemed to be that place. It was a livable city, there was not an obvious artistic style associated with it and where I would be free to try a bunch of different stuff without a lot of scrutiny. And it was and is the Queer capital and that was important. I think my work and my career has always benefited from taking a sideways step, from taking a step that was not into the center. I think I operate better on the periphery, moving between locations.

MD: I want to get back to that ‘in between-ness’ in a moment but I have one other question / observation first. One of my earliest memories of you was at your show at Patti Davidson’s Media in 1987which was one of the first galleries South of Market. You were chatting with some visitors and they were talking about Cal Arts and were a bit disparaging about John Baldassari. And in a diplomatic but firm way you told them they were wrong. I think it’s common for young artists to try to pull art stars from their pedestals. But you were very forthright and reasonable in your defense of Baldassari, not as an acolyte but out of respect. I was very struck by how protective you were of him. Do you remember that?

NB: I don’t remember that, but its funny because I just had a conversation with someone yesterday about an artist who is mutual acquaintance of ours in which a similar thing happened. After listening to several disparaging remarks describing this artist’s behavior, I took out a couple of books of their work and started to talk about some projects in relation to their personality. The tone of the conversation changed completely. I believe empathy is important. Its funny, my experience of John Baldassari at Cal Arts was very much a human one. He wasn’t teaching a whole lot at that time but was an important presence at the school but not in a dominating way. He was not an authoritative teacher, it was more like hanging out with him, especially if you knew jokes, he would love to hang out with you because he loved hearing and telling jokes. Doug Huebler was more of a teacher to me and although he is not talked about as much as Baldassari, I think he was an equally influential figure for a lot of people.

MD: That sense of empathy was clear to me from early in your career, that your ambition did not preclude concern and support for your colleagues and community.

NB: I believe in that very strongly. I was, and am, very ambitious, but ambitious for the work rather than the career, I don’t believe it’s a zero sum game. My big trick in trying to advance my career was by being a resource, by telling other people about the work of my peers, by spreading the news about things / projects / artists that I was excited about. Then people regard you as someone who is not simply interested in furthering their own work but can come to you as a source for information about new things.

MAD: Back to this ‘in between-ness’ you mentioned earlier. We both came of age as artists in San Francisco in the 1980s and I had been thinking about the ‘in between-ness’ of that time and place. Generationally we were between what you might call the radical conceptualists who opened up the art world to performance and site-specific sculpture / installation and who also founded the alternative space movement in the 1970s that were so important to us in our formative years. We were between the radical, anti-materialist, idealism of that generation and what you might call the art stars dominating New York during that time, people like Schnabel, Basquiat, Longo, Sherman, and the whole ‘Pictures Generation’ phenomenon. I think we had allegiances to both impulses – to the alternative and to the market – I found it a bit confusing.

NB: One of the things that characterizes San Francisco for me is the lifecycle of institutions. To put it simply – there are these established conventional and alternative spaces and every few years a new generation of artists comes out of the art schools, looks around and decides that none of those institutions meet their needs so they start their own. At the point we came into it, some people decided to do it privately rather than the not-for-profit route. San Francisco has a mature non-profit arts culture, New Langton Arts, Camerawork, Galeria de la Raza, Project Artaud, to name just a few, had Boards of Directors, had established fund-raisers and grant writers and the time line for creating something like that was too slow for what we wanted to do. So our impulse was to just open a storefront and do it ourselves. That was one thing that was really special about the ecology of San Francisco when we were there.

MAD: Well let’s talk about your artwork. During this period we are talking about you really mined thrift stores for material with which to make your sculpture. With found materials you can let the real world seep into the work via implied narratives, or the kind of patina or aura that an object might possess or suggest. But found objects also come with the danger of nostalgia.

NB: I don’t know where in my art training I got this, whether it was from Bard or Cal Arts, but I had this notion that if something is kind of successful in a piece, then you really have to confront that because its easy to allow something that works to become a crutch in your artistic endeavors. I think of every piece you make as a kind of crisis you are trying to solve. And you solve it by doing different things to it. If you know in the back of your mind that there is a certain thing you can do to solve that crisis, then there really wasn’t a crisis to begin with and at that point the work begins to cycle back on itself, reiterating style over invention.

When you are working with primarily things that you find, you are at the mercy of those things, so if you find something that’s really cool or interesting, great, if not, then you’re stuck. I realized that I had to start building my own things and try to examine the question of ‘past-ness’ that seemed to adhere to the things I was finding and kept attracting my eye. Also at that point I started to have a real problem with Barbara Kruger. (Laughter). Because her design choices seemed to situate the social problems she was addressing were in the past, in the 1950s. Later she stopped relying solely on those kinds of dated images, but at the time I was really conscious of how I wanted the work to be contemporary.

MAD: For one of your projects in the 1980s you raided second-hand stores for books and one of the things you talked about is how artists seldom admitted to the things they really love in popular culture, their guilty pleasures. For example that we had all read Lord of the Rings but we never talked about it, instead we haltingly spoke about Foucault, Derrida, or Benjamin, the stuff we were supposed to be reading to be theoretically informed artists. So when you used these mass-market books in your sculptures it was a way of celebrating or at least acknowledging its influence on us.

NB: Well it’s never the thing itself, its what you do with it. It’s disingenuous to act as if those things were never there. One of the things about Lord of the Rings is that it’s a great gay love story. The emotional romance in that book is between Sam and Frodo. That was a big thing for me when I first read those books as a kid. So why not think about that? I don’t think that is false consciousness.

MAD: Maybe this is not so true any more but in art school, I think we were taught or we inferred that some things or even materials are beneath consideration, embarrassing or shameful even.

NB: A lot of the work of that period began to investigate the shameful. If I have been told all of my life that a particular group of people are shameful, or that I have been told that my body is shameful, do I accept that or do I look at what that means and how its constructed. So in that sense there is something powerful in the thing we push away, the abject and the discarded.

MAD: Later in the 80s and into the 90s you began to work with stainless steel, leather, and fabricated objects. Also you used puppets, marionettes. Here the work becomes about, among other things, relationships and power, surrogates and masters.

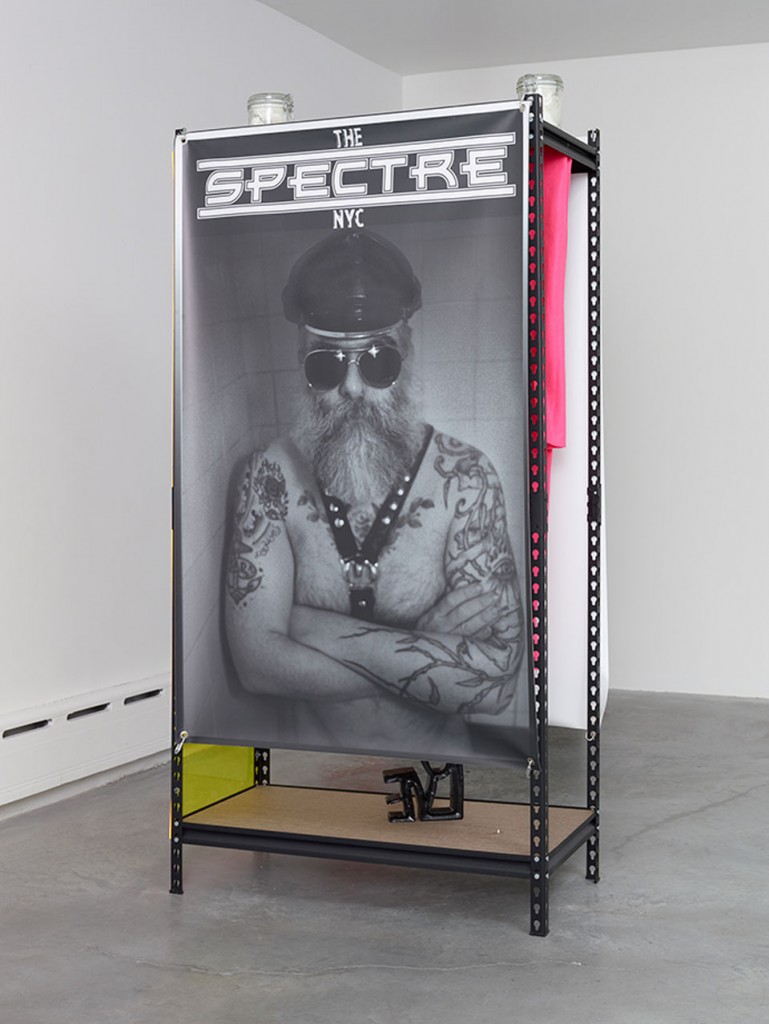

NB: I guess I believe that societal power relationships are also addressed on the personal level. My sister is much younger than me so basically I grew up as an only child and I would play board games with myself and try not to cheat (Laughter). I got used to playing dual roles, and I had lots of puppets that I loved. So in that sense the puppet has a personality, a voice that is distinct from the puppeteer. That is an interesting thing to think about, what costumes do, what clothing does in relation to character. So that’s how or where those things began to manifest in my work. More recently, actually over the last 10 years or so, I have been involved in the BDSM community and I really consider what I and other people do there as performance art. It is an environment in which the audience and performers are co-extensive. It’s about people making meaning for each other, using skills and physical experience. It’s about exploring that relationship to power in a very particular way. I meet people in that environment who are experts in that. One of the things I have learned there is that power is only problematic when it’s fixed, when it is not mobile. All relationships have power dynamics, it is only a problem when power accrues to a particular location and is not allowed to move to any other place.

Sometimes you want to be on the top, sometimes you want to be on the bottom and you see kids play with that dynamic all the time. I don’t think power is wrong in of itself; you cannot remove power from personal interactions. But you can examine power; is it fixed? Is it mobile? How does it move from one person or place to another? How does consent operate in any given dynamic. In a sense that is what democracy is – a power relationship based on consent as opposed to one based on force. And that is one of the things kinky people talk about a lot – what is consent? What does it mean? How do you confirm its existence? So that’s a place where these things are being talked about on a very deep level, certainly more deeply than the art world.

MAD: Your performance piece Gorge has gotten a lot of attention over the years but I would like to ask you about it a bit. It involves a relationship between you and another man, at least in its initial iterations.

NB: It started as a one-hour video. It’s a fixed shot; there is a clock on the wall in the background that counts the hour. I am seated without a shirt on and there is another man who enters and exits the frame bringing food and feeding me over the course of the hour and I eat whatever he offers me.

MAD: There’s a lot going on in this piece. The other man is dark skinned and you are apparently white – which is part of the subtext. There is play in the relationship, a flux between nurturance and force. It has become a kind of touchstone piece for you and you have re-staged it on occasion.

NB: Yes I have done versions as a performance where I am seated in front of a table full of food and people from the audience feed me over the course of the hour. It changes what happens but what links them is that its very rare that we watch somebody eat, even though we have meals with people all the time, we don’t sit and watch them eat. Also my presence is very neutral so that it becomes about what is going on in people’s minds while they are watching. When doing it live, everyone who feeds me becomes a performer and the last time I did it in 2010, it became almost vaudevillian, people playfully interacted with me, like someone putting food in their cleavage and fed me. But what was overwhelmingly clear is that the people who are watching realize that they have a kind of responsibility for me. Its not just about them watching but develop a concern about whether I have enough water or that I am not going to choke. That’s one of the reasons I have gone back to that performance because it creates a moment in which people cohere into a community and its not about being entertained but more, ‘how are we going to handle this situation’.

MAD: I am not the first person to observe the historical connection between Gorge and Yoko Ono’s Cut, Abramovic’s Rhythm Zero and Chris Burden’s Bed Piece, in which he lay in bed in the gallery for several weeks and people had to bring him food, water and something to pee in, etc.

NB: Well this is part of my pet theory that I am hoping to turn into a book which is about the rise of kink culture and the rise of body oriented performance art paralleled each other. There were very similar activities happening simultaneously in different places. Someone who was a bridge between those worlds is someone like Scott Burden, whose early performance pieces could have just as easily been acted out in the kink community.

I believe that this comes out of the New Left in the 1960s from people like Norman O. Brown and Wilhelm Reich who were trying to make a connection between psychology and socialism. Locating those things in people’s bodies, and how those bodies were treated. I think this is an important trajectory.

MAD: One other thing about Gorge; you’ve spoken about the experience of the audience but I am curious about your experience. The performer does things for an audience but is also creating an experience for him or herself. So what is your experience of Gorge, especially those live versions? You are sitting there for an hour and you put yourself at the mercy of strangers and you have to endure.

NB: Well I am accepting. When you narrate it that way two things come to mind immediately, cruising and meditation. My experience is like the latter, my attitude is ‘Lets see what happens’, I observe what unfolds, I experience it in a mindful way and this acceptance leads to interesting internal things. I am the center of attention while paradoxically not having a responsibility to that. I don’t have to worry about whether everyone is having a good time.

MAD: Lets talk about some more recent work, like those pieces you are doing on the street. While taking a walk you find a discarded paper cup or brick and then you do something to it, draw on it, write something and then you leave it, make a gift of it to the street or whoever stumbles upon it.

NB: I have been doing that for at least five years. It got started because I used to have a studio in Greenpoint and someone on the block had thrown out a futon and as I walked passed it each day it was growing more and more feculent. It pissed me off so much that no one was doing anything about it. Finally I painted a face on it and it was gone the next day! (Laughter)

MAD: We will have no more of this face painting on discarded objects! (Laughter)

NB: It got me thinking about all of my irritation with other people and my snarky waiting for things to get better and I thought maybe I could just fix little things myself. It also gave me the idea to leave things on the street for anyone who might find it. For a while I carried a whole kit in my bag of markers for every surface. It also came at a time when I was not feeling so great about the art world and thinking a lot about Ray Johnson.

MAD: There’s a little bit of fuck you in that gesture. Like who needs every work to be validated?

NB: Yes, but also the idea that the person who finds the work is the one who deserves it. One of the things I love about Ray Johnson was that he was willing to risk invisibility. And I think that is something that many artists have abandoned. If your work is so important to you, will you be willing to follow it wherever it might go, even if that place means few people will see it? I am interested in making something that someone may never see. I think there is a power in that, particularly living in a time of digital technologies that allow us to imagine that we can see everything.

We were speaking of the 1980s – I remember bands that may have only put out one EP or even a cassette, yet it could be so powerful and meaningful to one personally and even socially. So I have always thought that was another way of making and distributing work. I know that Ray Johnson was ambitious and he wanted art world recognition in a way that he did not receive it when he was alive, but he constructed an art world where he was king and here we are years later still talking about him.

MAD: You did a conversation with Rachel Harrison in Bomb a few years ago in which you stated that you wanted your work to be physical not just visual. And here we are sitting in your office at ICP where you are the director of the MFA program in photography. Do you think that kind of physicality you are talking about is possible in photography?

NB: Photographs are objects. Right after my show at Media in 1986, I had a show at Camerawork of stereoscope images that I shot, printed and presented with a stereoscopic viewer. It was a suite of stereo still life pictures presented in a little Victorian environment. So you had the images, the mechanism for viewing those images and the world in which the images were presented. One of my favorite things as a kid was the Viewmaster, I loved how magical and immersive it was. I think we always have to deal with the physicality of the photograph, even in today’s world in which we carry around a photo album with us on our phones. That is a different experience than seeing images projected, or on a monitor, or in a print. Each one of those viewing experiences is distinct from each other. I think one reason I was hired for this job was that I was not situated in any one are of the photography world. And a big part of what we do in this program is talk about how photographs exist and operate in the world. And that is unique to ICP’s curatorial program as well. That we are not just talking about some parade of great images but how, when and where images are produced, presented and consumed is a huge part of their meaning.

I guess one of the things I have come to say is that I am really interested in photography and photographs but I am not so interested in images. I think we are tyrannized by images at this point.

MAD: That contradicts the rhetoric of most art schools and art discourse where it’s not about photography, or video, or painting specifically but about ‘the image’. While this sounds smart or clever, it actually flattens important differences by plucking things from their material and cultural contexts.

NB: Weirdly enough, all of this stuff we have been talking about is related. The same physicality of the photograph is to me like my physicality of my own understanding of power relationships through bodily experience. I won’t let my students use the term ‘the’ body. I immediately ask whose body? I tell them to stop trying to make things sound important by putting the article ‘the’ in front of them. It’s not ‘the’ audience, it’s which audience. The temptation to talk about ‘the’ image creates an abstraction that removes us from specificity. It’s tied into how people talk about ‘desire’ and not about pleasure. It’s easier to talk about generalities, whereas pleasure, our bodies, this particular concrete object, is much harder to talk about, where our experience is particularized and unique. That’s the place where we have to talk because we don’t automatically have agreement and therefore we have to have a negotiation. We have to deal with the realities of our own power or disempowerment.

I guess that’s why I am a sculptor underneath it all. Sculpture is the place where ideas are made physical. The tension between the idea and the physical thing has really structured my understanding of myself in the world. It’s very easy to desire an image but lets talk about the pleasure you take in making a photograph. That’s the thing that leaves us more vulnerable.