Lee Gardner

Baltimore’s City Paper started publishing 35 years ago. Like many alternative weeklies all over the country, the City Paper has its roots in a series of cultural shifts that began in the 1960s that transformed journalism. The Village Voice, The Boston Phoenix, the LA Weekly, the Bay Guardian, the Chicago Reader and countless others were responding to constituencies that craved hipper, more progressive, and culturally diverse content in its articles about politics, art, books, movies and music. While these journalistic rebels still have some swagger, they have also become part of the established cultural landscape. Its hard to imagine navigating Baltimore’s fragmented yet thriving DIY culture, its underground music and its many artist run galleries, for example, without a dedicated cadre of writers to scope it all out.

Although I did not know it at the time, when Saint Lucy sat down to interview Lee Garder at the City Paper offices on Park Street on March 14, 2012, he was just about to announce that he was leaving the paper after 17 years to take a job as an editor at the Chronicle of Higher Education. In these years, Lee has contributed enormously to the public face of Baltimore: writing hundreds of articles and editing even more. His decisions as editor have helped to shape the public dialog on crime, corruption, gentrification, and municipal entropy. But beyond political issues, Lee Gardner has set a standard for celebrating Baltimore for its extraordinarily diverse, devoted and talented citizens.

Robbin Lee contributed to this interview.

We sat for a minute in silence as I fumbled with my notes

MAD: This is like a John Cage piece.

LG: Haha, observe four minutes and thirty three seconds of silence?

MAD: I just had some general questions that will get the conversation started. Thanks for making time for us, I really appreciate it.

LG: Yeah, sure. I don’t think I’ve ever done this before.

MAD: Really? That is surprising. So anyway, I was just wondering, how long have you been at the City Paper?

LG: Seventeen years, which does not seem possible.

MAD: And you’ve been editor for how long?

LG: Uh, nine years, so better than half the time.

MAD: And did you study journalism or literature?

LG: It’s a long and torturous saga. I did not go to journalism school. Most people who work at weeklies do not come from journalism school. If you go to journalism school there are all these hoops you are expected to jump through – an expected trajectory – attending a prestigious school, working in a small market at a newspaper or TV station, and then trying to get a job in bigger markets, and then hopefully working at the Washington Post or other established institutions. With the weeklies you can just kind of show up and if you can write and be reliable and work for the little money we pay you, you’re in! So the alternative weeklies tend to attract people who are not from a traditional journalism background, even though some people leave City Paper for dailies and other more conventional publications.

MAD: So you studied creative writing in college.

LG: Yeah, when I was originally an undergrad a billion years ago, I thought I wanted to be a fiction writer. I was a pretty good writer, but then I figured out, fortunately kind of early on, that I didn’t really have my own stories to tell. Like, I could write well, but when it came to what to write, I was a little bit at a loss once I ran through the dozen things I had in my head. But it sort of started to make sense to me that I could use the tools that I got from the creative writing classes and poetry classes to tell true stories. And I ended up getting an internship at a media company and they liked me a lot and hired me and I just kind of kept going from there.

MAD: That’s when you discovered long-form non-fiction writing? In some sense in reaction to not having an endless trove of stories and characters in your own mind?

LG: Well, I always was a reader and, I wouldn’t say I was a precocious reader, but I read a lot of weird things. As a teenager, I was a regular reader of Esquire magazine, which doesn’t seem normal. [Laughter] This was sort of like at a point where magazines were still, like the late 70s early 80s, where magazines were still very much kind of rolling on the new journalism thing. Magazine journalism still carried a lot of the characteristics of that, these long involved and detailed pieces of writing.

I did not want to take all the expected baby steps in a journalism career, you know, like writing obituaries and such. That did not seem appealing at the time. But I eventually started to make the connection that is the kind of writing that I could do. And you know, the first place I worked I didn’t get to write anything longer than 500 words, which is one of the reasons I eventually left. But it was good training, because the downside of coming into alternative weeklies is that sometimes writers lack the discipline one learns from having quick deadlines, severe word limits and a strict editor. That’s one of the things that journalism school is good for, for building a little bit of discipline into what you do and how you think about things. But the downside of that is it can make you too disciplined for other types of writing.

MAD: You used the term ‘new journalism’ which is a broad description of a kind of activist or eccentric writing about cultural and political issues that came about in the 60s and 70s.

LG: Yeah and very much one of the wellsprings for the alt world.

MAD: So I wanted to ask you about the legacy of the alternative weekly. There are and have been so many influential alternative weeklies over the years, like the Village Voice, the Boston Phoenix, the LA Weekly, the Baltimore City Paper, to name a few. I’m just wondering, is that legacy important to you? Do you feel like there’s this some kind of responsibility on your part as the editor to kind of keep that legacy alive?

LG: Yes, in a lot of ways. I can’t say we are the last refuge of the 5,000-word cover story, but were increasingly one of the few that will stretch out like that. Although most of our bigger stories are a bit shorter these days than they were 4 or 5 years ago. But yeah, there was a whole generation fueled by new journalism and Watergate that really embraced the possibilities of true stories, creative non-fiction as it’s now called, where you’re not just reporting the facts, you’re observing the facts and making something out of them, narratively and philosophically, that might not have been there if you were just watching and writing down what happened. Yeah, so I think it’s important for the alts and I think it’s important for me personally. As much as I understand the importance of brevity and discipline, and as much as I understand that people don’t really have the time or the interest to go through a multi-thousand word feature story, I kind of take that a little bit as a challenge. You don’t want to bore people or just take up their time to take up their time. But if you have a good story, and you can tell it in a way that’s going to keep it compelling, then you know, that’s still lots of fun.

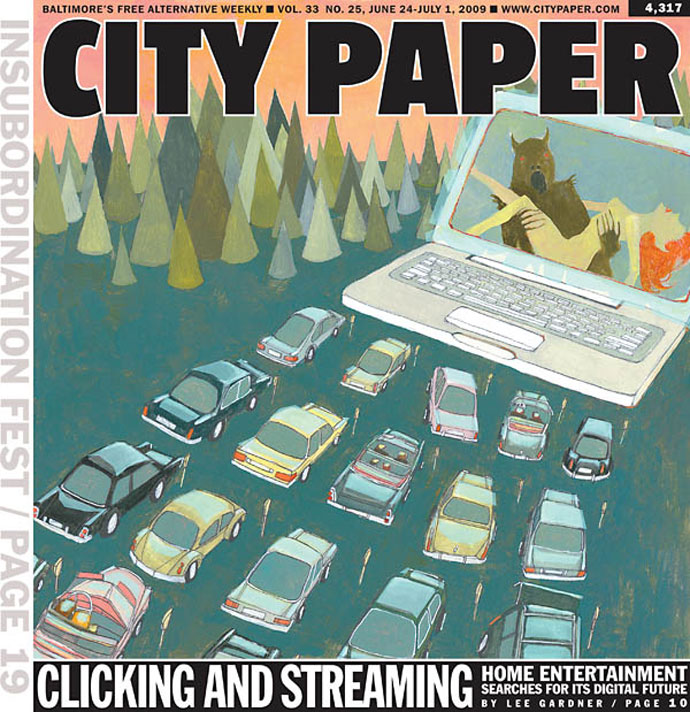

MAD: So the relationship between printed journalism and online journalism; what do you think a printed weekly can do that an online journal cannot? Is there some difference there?

LG: There are differences, but the… now a lot of the differences are compensated for. The argument might have gone, several years ago, that we can do more with graphics, in terms of big photo spreads and things like that [in print], but you know, now you can have slideshows and can reproduce with pretty good resolution all sorts of images on the web, and that’s something we can’t do in print. The web’s a lot faster. Having a weekly production cycle as opposed to a daily production cycle, always forced us to be commentators. We were not able to break news, but we could have a better angle on stories sometimes since we have the time and space to process and contextualize.

MAD: I suppose it’s generational but since I grew up with books, magazines and newspapers, I prefer to read longer pieces of text in that format. I do spend enormous amounts of time online but there’s something about the physical relationship to the paper and the turning and the sort of, I don’t know, sitting in the cafe in front of the screen does not seem fun to me. It’s not sensual enough.

LG: One of the things that I learned pretty early on being an editor is if you’re reading a story like you’re editing a story, you should always print it out and look at it [on paper]. Because you will see things on paper that you will not see on a screen and I don’t know why that is. I guess because you’re seeing more of it? Or you’re seeing it in a way that’s where it’s literally it’s not sort of doing that miniscule pulse that stuff on a screen does. You see things on a paper read that you don’t [see on a screen]. I teach [college] classes sometimes and I always tell the students, print your paper out and read it and read it loud and you will find stuff that you would have been horrified to turn in.

That said, it was a very revelatory and sad moment for me when I realized I liked reading New York Times online better than I like reading it in print. And it may be small-minded and sort of dumb, but I hate how everything jumps off the front page. And that’s one of the constraints of the way that print publications are sometimes designed and, you know, the websites run into the same thing too where everything has to be in the front. You know, you want everything to be prominent, but everything can’t be prominent or nothing is. When you read a physical copy of the New York Times and you get to the end of the little column on the front, then you have to go find the rest of it in the back of the paper. And I was just sitting there and I was like, this is annoying and if I was reading online I would just scroll to the bottom of the page and click and read the rest of it and it would not be all this shuffling. And so, I was kind of… it was a little sad, but yeah, it’s true, so.

MAD: I’m still addicted to the Sunday paper. Cause I feel like that has to do with leisure. But not getting the paper every day I feel less guilty about all those dead trees.

LG: Well print newspaper, I mean I read, we get the Sunday Times too, which is the only physical edition of the Times we get. But that’s different and it’s given to you differently. It’s bigger, it has more stuff, it has a lot more sort of room in it, like weekend review stuff, but it’s like a print newspaper is becoming like brunch. You know, you can do that on a Sunday because you have some time and it’s a little bit of ritual and it’s sort of this other space, but you can’t do brunch on a Tuesday, you know, unless you’re unemployed I guess. But, you know, it’s different. And for that, you have your Twitter feed, or you’re looking at it on your phone or your iPad or your laptop or whatever.

MAD: Robbin, since you have grown up with the internet – what do you think?

RL: I agree with everything you’re saying. I mean, I get most of my news from people posting about news on Facebook or Twitter. And then, like you said, I get really guilty when I have piles of Time magazine, or newspapers in my room and I just don’t have time to read them. Just being a busy student, you know.

LG: I was just talking to a friend of mine last night about the weird guilt that people feel. He had just bought a Kindle and he was thinking about how much he loved books, like physical books, and how much it felt sort of like a betrayal to be buying something that would be a part of the destruction of the print publishing industry. But it’s like, you know, at a certain point you can’t feel too bad about it or you can’t feel guilty because this process has gone, not necessarily this technology, but this process has gone over and over again for thousands of years where the way people do things and get attached to doing things changes and you can feel bad about it, but it won’t actually do any good to feel bad about it. And you know if the ease of use or the way things work changes enough, it won’t matter how many people feel bad about it, it will just happen anyway.

MAD: There are still good, smart, conscientious people producing content and the format changes, the delivery changes, but there’s still people out there trying to connect to the world or witness the world or whatever it is.

LG: Yes and there are sort of counter-movements. The way that vinyl has come back, I think, it’s really filled a hole for people for whom there’s this sort of acquisitive, tactile part of music. It’s not just ephemeral downloading but more like you own the music when you have it on vinyl. You can’t take out your iPod and say look how many gigs I have, that doesn’t matter to anyone. And that’s part of it, that’s part of that sort of physical thing.

RL: Recently I talked to Alan Rutberg at Own Guru Records in Fells Point, and he was talking about how you know when things become obsolete they become art. You know, like records, they’re obsolete now, but they’re always going to last because there’s always people that want to see the grooves in the vinyl, see the album art. So I feel like the same thing with books and just publishing, I mean print publishing, it’s not going to die, but it may become like high art.

LG: Yeah, or definitely more of a boutique thing.

RL: I think in a way it’ll become more valuable, because you see less of it.

MAD: So I was looking through the City Paper online archives, at some recent articles you’ve written.

LG: Oh my.

MAD: I was impressed by how prolific you were.

LG: Well it is 2012. You must produce. Smaller staffs and you know, but… the nice thing is, and weeklies always kind of tend to attract people who want to do a lot, who are involved in and interested in a wide variety of things. That’s a good quality to look for in someone who works for a weekly cause you’re going to dive in, so everybody gets to dive in real hard.

MAD: So you wrote a review of the film Friends with Kids, you wrote a restaurant review of a Russian deli. You wrote a piece about the Romanian dictator Ceaușescu, and a meditation on the end of the Iraq War?

LG: Yeah…

MAD: Your role is to be an uber-informed citizen.

LG: Oh, well I guess that’s what I’m supposed to try to impersonate at least. I have written about movies and music for a long time. That was kind of mostly what I’ve written about over the whole time I’ve been doing this. And as the editor, it’s part of, it’s incumbent on me to sort of you know address the weighty topics of the day every now and again. And sometimes I’m not always in the option of picking and choosing what I have something to say about. The Iraq war thing, I mean we’d been running the climbing number of soldiers killed in the paper, they’re either on the cover or on the mail page since, gosh, 2004. And the Iraq War ended so I felt like I had to say something to explain that we’re going to keep running a number. I end up writing about politics too and not because that’s necessarily something I spend that much time on every day or every week, but as the person that handles the news coverage these days too, it’s something I have to be up on and try to address myself or with the staff. And I’m lucky to work with really good reporters, so.

MAD: Do you ever get sick of having opinions?

LG: All the time, yes.

MAD: Do you feel plagued about all your opinions? I know I am by mine. [Laughter]

LG: I do. I remember when the movie Inception came out, I did not review it. I wasn’t reviewing movies as much then, Bret McCabe was. And I went to see it and immediately after the credits rolled, I decided I didn’t want to talk to anybody about it. Because everyone was like, “Oh man, this is great. Oh, that sucked, that was terrible,” and they were picking it apart and they were trying to figure it out and it was just like, you know, I enjoyed that and I’m not going to talk about why or tempt anyone to try to argue me out of it or try convince anyone else who didn’t like it that they should. I’m just going to have enjoyed that and leave it alone and that’s what I did.

That being said, it’s nice to have a platform to say, “This is really good and you should go see it!” But you know, was I looking forward to writing about Friends with Kids? Not to pick on it, but not that much. But it was kind of interesting to write about because it attempted to do something that it didn’t do very well, although it was sort of a good attempt, but not good enough.

MAD: I have to say that in terms of entertainment in the city I don’t participate much, I hardly see any movies or live music lately, but I can’t imagine life without a weekly like the City Paper because at least I know what’s going on at the Charles or the Windup Space or whatever it is. It’s really important to me, makes me feel less lonely in some way, there’s a lot of things going on that the city is thriving culturally.

LG: Every Sunday, the first thing I read is the book review in the New York Times book review. Part of that is because it’s a tabloid format, so I can put it in my lap while I’m eating breakfast. So it’s logistical. But also, it’s like, that’s one of my favorite things in the Sunday paper and I will, you know . . . historically, I read very few of these books, I just don’t have time. But I like sort of knowing what’s out there.

RL: So how do you handle the grey area between work and just life? It seems like journalists are always looking out for the next story. Is that true for you? Or you just go about your life and they fall in your lap or…

LG: Sort of. I have a staff job, which is nice, because there are times when I can just not pay attention to things, but freelance writers, you know, the old joke about freelance writers—it’s not really a joke I guess because it’s not that funny—is that they’re always hustling because everything becomes a story. You know, they go to the co-op to pick up something and they see some weird vegetable that they’ve never seen before and all of a sudden, “Oh I’ll pitch this editor on a story about weird vegetables!” Everything becomes something that you’re going to try to turn into a story and sell. I have to kind of try to pay attention to what’s going on, but I don’t feel overburdened about being an editor or anything like that, you know. I see what you’re saying and I guess my answer would be that I am fortunate not to feel that too keenly.

RL: And you live in Baltimore? Are you very involved in the community or do you stay outside it?

LG: Yeah, well I mean I try to be. I kind of give it the office. I’m not from here and I have said before that I’ll never really be from here because I didn’t go to high school here, but I’ve lived here kind of a long time now, and my wife is a native Baltimorean as are my kids, and I don’t have any big plans to leave anytime soon, so. Sometimes you hear people say, “Well when I woke up this morning, I wasn’t planning on this.” Whatever it is they find themselves doing. And I guess I think that sometimes. It’s like, wow, I ended up in Baltimore, how funny is that? But I did, and that works for me.

MAD: So if you didn’t have this relentless weekly deadline and had a generous budget, would what you would be doing be very different?

LG: You mean, me personally?

MAD: I mean as a writer/editor.

LG: Umm, no, I mean, frankly, I like working for other people. That is, I don’t think I would go off and start my own magazine. Although … Yeah, I don’t know, that’s a good question, and I don’t really have a snappy answer for it. If I won the lottery or something, or didn’t need to, you know, come into the office everyday to keep the family supported and all that, I would still want to write and work on some bigger projects, maybe book projects that I wanted to do but am not really in a position to be able to do. You know, I have a full time job and a pretty demanding one. But yeah, I would have to keep writing and paying attention to stuff cause that’s, it’s not by accident, I guess, that I ended up doing this sort of thing that I do.

MAD: But is there a book that has yet to be written?

LG: I had a couple three good ideas for book projects about 10 years ago. And over the years, I watched each of them get written by someone else. And in some cases by people who did far better job with it than I ever would have and in other cases people who, you know, I could’ve done a lot better than they did. And I’m kind of hatching a new crop of those ideas and then maybe this time I’ll actually get to one or two. So you make a good point. It seems like everything has been done to death. And there are plenty of books that are just like, ugh, really, this again? But, I would like to at least take a crack at some point.

MAD: You can write a memoir about how strictly you raise your children.

LG: Haha, that would be a very short memoir. No, and I hate writing about myself, so I don’t think I would ever do that. You know, I hate writing first-person things. I don’t know why.

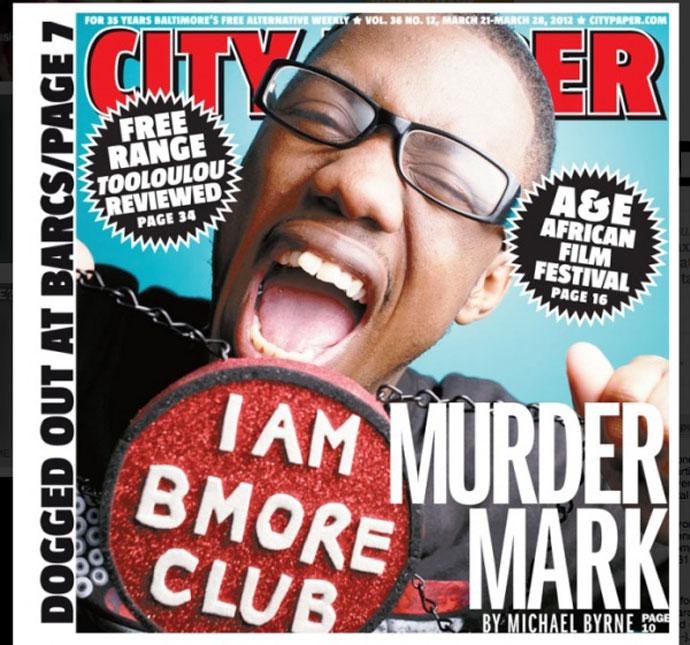

MAD: A really prominent and disturbing feature of the City Paper is Murder Ink. It tries to provide some backstory to murders that are committed each week in the city. This column is a kind of prominent measuring device for the city – like how bad is the violence now, compared to last year. Was that something instituted under your watch?

LG: It was something that Erin Sullivan, the former managing editor, started with Anna Ditkoff, who still writes it. She’s not with City Paper anymore, but she was on staff for many years. But it came out of discussions about the way that murders at the time were reported on here, or were not very much. And you know, at one point, the Sun was running a chalk outline with a number superimposed on it for the number of murders for the year, and it was just like… I think it just sort of struck us, like, this is not good.

MAD: Because it’s purely symbolic and doesn’t tell any, doesn’t give any sense of the individuals involved.

LG: Yeah, yeah. It was just like a baseball box score. But, yeah the idea was that these are people and these are circumstances. All these victims were related to someone, someone’s son or daughter, girlfriend or boyfriend or father or mother. They weren’t just these numbers falling off the map somewhere at the edge of the city; it was people with lives that got taken. You know, but at the same time, we only have so many resources. We can’t investigate and report fully on the circumstances that led up to every murder or what happens afterwards. We do updates so we can un-abstract it a little bit. We can only do so much.

MAD: But it’s an important, you see as an important commitment of the City Paper to continue that?

LG: I think so. The murder rate has been nearly cut in half, although there aren’t many good blanket explanations for why that is. But you know, we still have a lot of murders for a city our size, or city of any size really, per capita.

RL: Just from my perspective as an intern, you know, I just kind of wanted to know where you started off, in terms of journalism.

LG: I interned for a travel publication for college students. And they liked me, thought I was sharp, something like that, and I was really fortunate that an editor, Carole R. Simmons, said, “I’m going to teach you how to do this” and she did. She got me started into paying attention to, not just writing, but how you’re writing – did it cover these certain bases and was it clear and can it fit in this space? Editing is a whole different thing from writing in many ways. What you’re trying to do is make a good story, but it’s a process, you’re working with another person, so it’s not just “I hate this” but I am going to change it.

RL: Did you ever have to write obituaries?

LG: No, although . . . I never did it in the daily sense, where it’s just some person who dies and you have to sort of put together this little account of their life, you know, which is a whole art form in itself really. But I did start doing a thing at City Paper, that we still do, called People Who Died because it’s just fascinating.

MAD: That’s a once a year thing

LG: At the end of the year. I would hear about people who died and they would mean something to me, like Samuel Z. Arkoff, I think, was one of the first ones I ever wrote. He was a guy who produced crappy B movies and he had a great name and when you would watch one of his movies, these huge letters A SAMUEL Z. ARKOFF PRODUCTION would scroll down during the credits. And it was just so weird cheesy and colorful and I remembered that. And one day I read that Samuel Z. Arkoff had died, and it was like whoa! You don’t even think of someone like that as a real person, and he had stopped making movies decades before he died. And it got to me, it was like, someone should remember Samuel Z. Arkoff because he made crappy movies, but they were great crappy movies. And it turns out, once I started looking into him, that he was sort of one of the people who first sort of started making movies for teenagers, which is not something people did before like the late 50s early 60s. They made movies for everyone, sort of, but they were mostly for adults, you know. They didn’t make like trashy movies that would appeal to teenagers with monsters and you know juvenile delinquents in the 50s. He was the guy that started all of that.

RL: Who’s the weirdest person you’ve met through this job? There are some eccentrics in Baltimore.

LG: I don’t know if I have a good story for this. I mean, I run into weird people all the time, but I don’t know if you could say I meet them, you know. I don’t know, I don’t think I have a good answer for this.

MAD: But related to that, do you think that Baltimore lives up to its eccentric reputation, so much burnished by John Waters.

LG: I think every place is pretty weird if you know where to look, you know. I haven’t spent that much time in Iowa or Missouri, so maybe they’re not that weird.

RL: Maybe you’re just used to it.

LG: Well, you know, I’m from Tennessee, which is in many ways, a not-weird place at all, its very much a respectable bible belt territory, but in other ways it’s really weird, you know if you start paying attention………